Early in the twentieth century there lived in Greenwich Village a few hundred women and men who were bent on making a revolution not so much in politics as in consciousness. Among them were artists, intellectuals, and social theorists for whom the words free and new had achieved a reverential status. “Free speech, free thought, free love; new morals, new ideas, New Women”: these phrases had become catechisms, crusading slogans among those flocking to the Village in the early 1900s, many of whose names—Eugene O’Neill, Mabel Dodge, John Reed, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Max Eastman and his sister, Crystal—are now inscribed in the history of the time. To experience oneself through open sexuality, irreverent conversation, eccentricity of dress; to routinely declare oneself free to not marry or have children, free to not make a living or vote—these were the extravagant conventions of American modernists then living in downtown New York.

Most of these people considered themselves socialist sympathizers at the same time that they placed individual consciousness at the center of their concerns. They did not read Marx anywhere near as much as they read Freud, yet a major difference between them and European modernists was the expectation that in America social change would occur as much through progressive politics as through the arts. The push for labor reform especially provided drama enough for Greenwich Village radicals to feel themselves living an urgent life while in its service. There were headline-making strikes in those years—the shirtwaist makers’ strike in New York in 1909; the Lawrence textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912; the Paterson, New Jersey, silk workers’ strike of 1913. All saw Village theorists on the picket line, Village painters producing propaganda art, Village journalists feeding strikers’ children—and always among them a significant number of the women who belonged to the Heterodoxy Club. The life and times of this club is the subject of Joanna Scutts’s lively and absorbing new social history, Hotbed.

On a Saturday afternoon in 1912 a group of twenty-five women—all white, all educated, and mainly well-to-do—met in Polly’s restaurant at 135 MacDougal Street in order to form a club for self-declared feminists with a craving for good conversation. Polly’s was located in the building’s basement, while upstairs resided the energetic Liberal Club—which supported an avant-garde drama troupe and threw fund-raising costume balls—and next door would soon be the Provincetown Playhouse, where Eugene O’Neill’s work was regularly shocking somebody or other. In short, this was the heart of bohemian Greenwich Village, home of the intimate relation between art and politics: exactly where, in 1912, these women felt they belonged.

The only requirement for membership in the club was that the applicant not be a person of conventional opinion. In fact, announced the founder, suffragist Marie Jenney Howe, they would call their club the Heterodoxy and themselves the Heterodites. The club had no bylaws, took no minutes, conformed to no agenda. Heterodoxy was to bring together writers and lawyers, actors and academics, anthropologists and labor organizers for the pure pleasure of lively exchange, of which there was sure to be much. They were working women, each with a pronounced interest in not only suffrage for women but economic justice and freedom of expression for all.

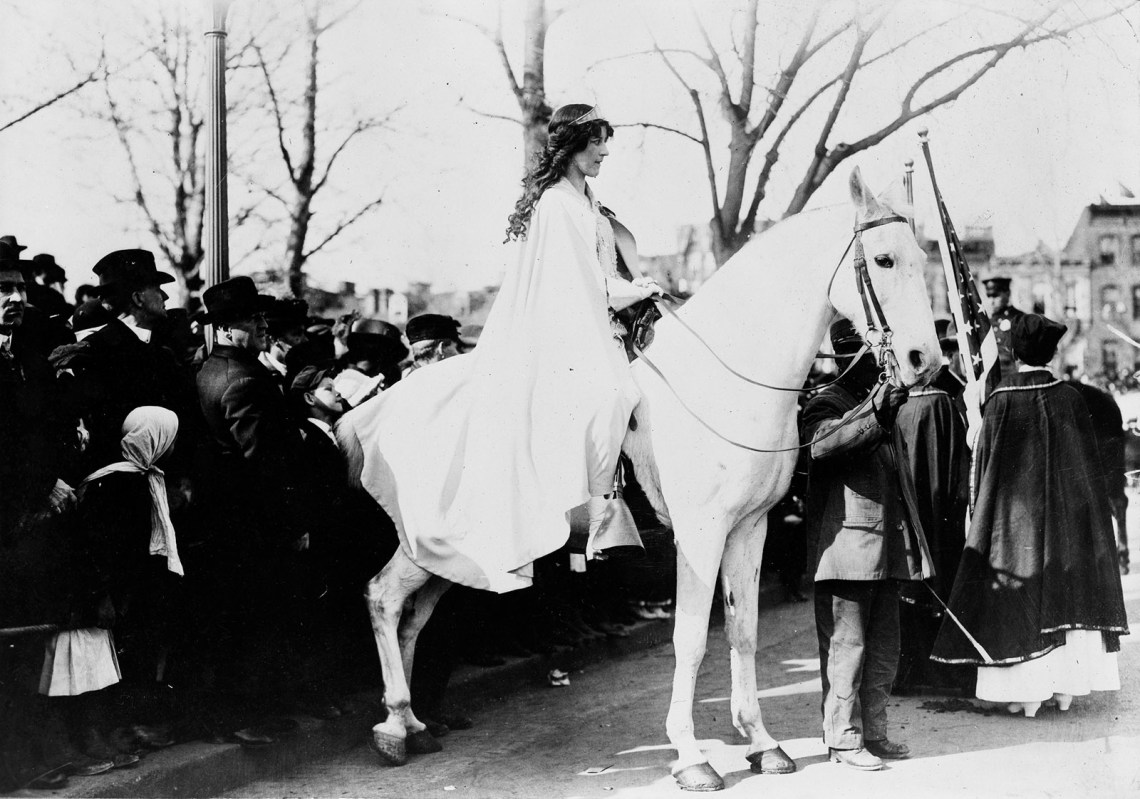

Among those early members of the Heterodoxy Club were Charlotte Perkins Gilman, feminist historian and author of the famed novella The Yellow Wallpaper; Mabel Dodge, bohemian salon keeper; Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, radical labor organizer; Fannie Hurst, waitress, sales clerk, and later Depression novelist; reporter Mary Heaton Vorse; labor journalist and lawyer Crystal Eastman; lawyer and labor reformer Inez Milholland; and radical feminist Rose Pastor Stokes. As Vorse said of the Heterodites: “Everybody a Liberal, if not a Radical—and all for Labor and the Arts.” They had one other thing in common: a shared predilection for a brand of wildly interruptive talk they chose to call debating. Those alternate Saturday afternoons when the Heterodoxy was in session at Polly’s were, in the years surrounding World War I, famous and infamous for the noisy intelligence that these often brilliant women brought to the contemplation of radical causes.

Almost every issue of the day engaged the interest of Heterodoxy women: besides suffrage, that included Freudian analysis, labor reform, birth control, and the freedom to speak and write one’s mind. And then there were the subjects that spoke to the inner life: sex, love, work; marriage and friendship. Friendship in particular was a relationship most radicals took seriously. Many of the Heterodites developed friendships of a high and original order during their years in the club. Marie Jenney Howe wrote to a candidate for membership, “Heterodoxy is the centre of more real friendliness among women than any group I know. This is its chief recommendation.”

Advertisement

Howe was hard put to explain what she meant by “real” friendliness, and Scutts herself, a cultural historian, sounds halfway mystical when she describes friendship as “something organic, unspoken, a connection that doesn’t require work or analysis.” She does better when she writes, “Together, the women of Heterodoxy pushed each other toward a new way of living. Everything from the way they dressed to the company they kept and the causes they championed was self-consciously new.” Most especially it was through the causes they championed that Heterodoxy friendships flourished.

They were, in the words of Mabel Dodge, “women who did things—and did them openly,” the operative word here being “openly.” They were each trying to live as men lived, which, preeminently, meant that every woman must make her own living. This issue of economic independence was immensely binding. On its shared ground, “an actress and a child psychologist, a textile artist, a labor organizer, and a satirical poet could meet and make friends.” The preoccupation alone separated the Heterodoxy from almost any other kind of women’s club one could name, which at the time were routinely focused on food, fashion, domestic concerns, tips on how to be happy, and certainly not intellectual exchange. This worked its members into a “tight-knit” group that helped each member to sustain her involvement in the cause close to her heart.

Another major cause for many in the club was the alleviation of the wretchedness endured by women factory workers, partly because of the Heterodites’ “own complicated yearnings to be self-supporting through their labor” but mainly out of sympathetic horror at the conditions in which these women lived and worked. Inez Milholland, a dedicated feminist (although often noted more for her beauty than her intellect), for one, could never get over the irony of the anti-suffrage argument that women’s place was in the home when “nine million of them were out at work in mills and factories.”

The same issue repeatedly threw her great pal and sister Heterodite, Crystal Eastman, into despair. Two weeks after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, Eastman gave a speech at the American Academy of Social and Political Science in which she said that when we know that a disaster has occurred because the law of the state has permitted the absence of safety measures, “what we want is to put somebody in jail,” but “when the dead bodies of girls are found piled up against locked doors leading to the exits after a factory fire…what we want is to start a revolution.” Together, Milholland and Eastman worked passionately over the years for suffrage, worker legislation, and what we now call civil rights. Ultimately, Eastman cofounded the ACLU.

The 1912 Lawrence strike of mill workers brought together another somewhat unlikely pair. For both Mary Heaton Vorse and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn the strike was a life-changing event. Flynn, twenty-one years old in 1912, was already something of an organizing phenomenon. The daughter of an impassioned Irishwoman whose triple hatreds—the British in Ireland, the degradation of the working class, the second-class status of women—had been swallowed whole by her responsive child, Elizabeth had left school at seventeen to become a full-time worker for radical causes and discovered she had a gift for organizing that made her presence on the soapbox magnetic. Like Emma Goldman, she had the ability to make her working-class listeners feel dramatically the circumstances shaping their lives and long to take action. Later she became a much-demonized Communist, but at the time of the Lawrence strike, her eloquence sounding like a call to arms, she was often referred to as labor’s Joan of Arc.

Vorse, on the other hand, thirty-seven years old in 1912, was an experienced journalist who had grown up in a prosperous middle-class family. She was married with two children, living in Provincetown, Massachusetts, then Venice, Italy; when her husband died, in 1912, she married again—and then fled for Greenwich Village, where she became a writer who managed to straddle the line between liberal and radical. She wrote for such establishment venues as the New York World, The Washington Post, Harper’s Weekly, The Atlantic Monthly, and The New Republic—and she wrote for The Masses as well.

The problems of labor drove her to concentrate on them professionally, but it is my impression that at the end of the working day she could more or less put them aside. During the Lawrence strike, however, she and Flynn were often thrown together and, if anything, the mildness of the older woman soon gave way to the urgency of the younger one. Under the tutelage of the red-hot Flynn, Vorse found herself gripped by the meaning of class war and never again put it aside. The revelation transformed her into one of America’s most radically left-leaning journalists. Later in life, writing of the Lawrence strike, she said, “We knew now where we belonged. On the side of the workers, and not with the comfortable people among whom we were born…. I wanted to see wages go up and the babies’ death rate go down.” She also often said of the political education she owed to her friendship with Flynn, “There must be thousands like myself who are not indifferent, but only ignorant.”

Advertisement

Then there was the anthropologist Elsie Clews Parson, one of the boldest of the Heterodites on matters of love, sex, and marriage. She wanted to see trial marriages, divorce by mutual consent, and reliable contraception become the law of the land. Sex should be a practice separated by law from marriage, she said, which had to do with raising children, while sex had to do with the restless, ever-changing activity of the inner life. She once wrote in her journal, “This morning perhaps I may feel like a male; let me act like one. This afternoon I may feel like a female. Let me act like one. At midday or at midnight I may feel sexless; let me therefore act sexlessly.”

Like Parson, who lived successfully apart from her husband, Eastman tried a similar arrangement, but the experiment failed miserably and the pair separated. She was ever hopeful, however, that part-time marriage would prove a convention of the future. She thought this because she saw in herself—and certainly in her sister Heterodites—a hunger for that separateness of self she’d come to understand was necessary for genuine connection with one another.

I was one of those Second Wave feminists who adored the nineteenth-century suffragists. I envied them their political intelligence, their organizing skills, their staying power. Researching their letters and journals, their convention notes, their testimonials, their annual petitions to the government, I felt viscerally what it meant to identify with The Cause. And then again I was impressed by the friendships they sustained throughout their often thirty, forty, or fifty years of on-the-road activism, forged through a penetrating sense of the human condition as exemplified by the struggle for women’s rights. But it was only after I read Hotbed that I realized the type of feminist friendship from which I am more directly descended was that of the Heterodites. I speak here of the relationships that flourished in the 1970s and 1980s under the feminist practice of “consciousness raising,” which, like the Heterodoxy, made use of intellectual exchange influenced by an amalgam of Marx and Freud threaded through a liberationist rhetoric appropriate to the time.

“Consciousness raising” was what Second Wave feminists called examining one’s personal experience in the light of sexism, the theoretical explanation used to account for women’s centuries-long social and political subordination. Following a set of rules laid down by the New York Radical Feminists, CR groups in the main consisted of ten or twelve women who gathered once a week, sat in a circle, and spoke, each in turn, on a predetermined topic that seemed relevant to the idea that the personal is political. The result was something like shaking the kaleidoscope of history: the pieces remained the same, but the design that emerged was shockingly new. The average life of a consciousness-raising group, I noted then, was a year to eighteen months. In 1971, 100,000 women in the United States were enrolled in these groups. For women’s liberationists CR had become a powerful technique for feminist conversion.

The most striking part of this practice was the eventual recognition, among women whose stations in life varied significantly, that some fundamental sameness of being determined the way their lives had taken shape. For instance, at a CR meeting in suburban New York, the question “Why did you marry the man you married?” was posed, and a middle-aged office manager was stunned when “we went around the room, [and] the word love was never mentioned once.” Then an actress said, “I’ve been married three times and I’m amazed, if not ashamed, to say all three marriages sort of morph into one another.” Whereupon a working-class divorcée confided to me, “I’d walked into the room thinking, ‘None of these broads have been through what I’ve been through,’ but at the end of that session I thought, ‘They’ve all been through what I’ve been through.’”

Each woman spoke with a sense of wonder in her voice, as though she were seeing something of immense value that she’d never seen before. That something was herself thinking about her life as though it were a construct worthy of intellectual examination. Not only worthy, but needful. I’d recently met a fifty-year-old woman who’d just received a Ph.D. in biology. When I asked her why she’d gone back to school in middle age, and why biology, she said, “All my life, when asked my opinion on something, I’ve said, ‘I feel…’ I went back to school because I wanted to say, ‘I think…’” I recalled this woman often, especially in CR sessions where all the women, when asked about their lives, had initially responded with a surge of emotion rather than analysis, reinforcing the conventional wisdom that women by nature are passive participants, not acting authorities in charge of their own development.

The excitement that characterized these sessions never lost its edge. Essentially, it was the atmosphere created by the sound of women catching fire from one another, all of them determined that the conversation would arrive: give them something useful to take home. Here’s an example of how a CR evening might have gone:

A woman described walking down the street on a bright spring day when a man standing in the doorway of a shop said to her, “Smile, honey. Things can’t be that bad.” Puzzled, she told her CR compatriots, she looked quicky at her reflection in the shop window to see what he had seen in her face to make him say what he had said to her. She shrugged: “It was just a face at rest.” Another woman in the circle then said, “Maybe he thought you were depressed,” and a third quickly responded, “It’s not that he imagined she was depressed, it’s that he suspected she was thinking.” A fourth woman then said, “It makes them anxious when you stop smiling. To be masculine is to take action, to be feminine is to smile. Men often remember their mothers as always smiling.”

Woman five: “My mother is always telling me that she’s lived only for the family [smiling when she says this], and I always feel like saying to her, ‘Why don’t you live for yourself?’”

Woman six: “That used to be considered a moral virtue, living for the family. I’m sure lots of men feel the same way.”

Woman seven: “When a man says he lives for his family it sounds positively unnatural to me. When a woman says it, it sounds so ‘right.’ So expected.”

Woman eight: “God, this business of identity! Of wanting it from my work, and not looking for it in what my husband does.”

Woman nine: “Knowing where you stand in relation to other people…not because of what other people want of you but because of what you want for yourself.” She stopped to absorb what she’d just said. “Knowing what you want for yourself”—again that wonder in the voice—“that’s everything, isn’t it?”

Many of these exchanges may sound dated now, but at that time, in that place, they felt earth-shaking. Only a decade earlier they were unthinkable. No one would have had a useful thing to say after “Smile, honey.” But in the Seventies and Eighties, as Crystal Eastman and the Heterodites might have put it, those words made you want to start a revolution.

It’s hard to explain the exact nature of the friendships formed during these sessions. Circumstantial they certainly were (I don’t know how many CR participants remained in touch after they left the group), but haunting nonetheless. We were groping our way out of Plato’s cave, struggling to arrive at a clarified sense of self—and we were doing it in one another’s presence. This last, I think, was crucial. Whatever shape our efforts took, they were sure to be received with a sympathy that was not only informed but unstinting. This resulted in an atmosphere that made our connection to ourselves feel vital. Something oddly tender in this alchemy then made our connections to one another seem binding. I’d bet that the Heterodites, who rarely, if ever, had the language with which to express such emotional complexity, nonetheless felt the same toward one another.

This Issue

August 18, 2022

Egregiously Wrong

The Irish Lesson