Among the thousands of cases the Supreme Court has decided, only a handful of dissenting opinions stand out. There is Justice John Marshall Harlan’s solitary dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 decision upholding the doctrine of “separate but equal.” “All citizens are equal before the law,” Harlan objected. “There is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens.” Another is Justice Robert Jackson’s warning in Korematsu v. United States—the 1944 ruling that upheld the wartime internment of more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens—that the Court had delivered a decision that “lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion in the 2013 Shelby County case that eviscerated the Voting Rights Act—throwing out the law “when it has worked and is continuing to work…is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet”—has also made it into the canon. The opinion written jointly by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan in dissent from Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision that overturned Roe v. Wade in June, is likely to find its way there as well.1

Another Breyer dissent, in the 2007 case Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, rarely makes such lists today. The decision, which invalidated modest efforts by two public school systems to resist the tide of resegregation, received a fair amount of attention at the time—and so did Breyer’s dissent, which he delivered from the bench on the final day of the Court’s 2006–2007 term for an astonishing twenty-two minutes, the longest oral delivery of any opinion, majority or dissenting, in Supreme Court history.2 But memories have faded as other sharply contested cases have filled the Court’s docket. The legal historian Melvin I. Urofsky, in his Dissent and the Supreme Court: Its Role in the Court’s History and the Nation’s Constitutional Dialogue (2015), briefly discusses the case without even mentioning Breyer’s opinion.

Parents Involved is important nonetheless. The question at its heart—whether student-placement policies or, by extension, university admissions programs can ever take account of race—is arguably even more relevant now than it was fifteen years ago. Chief Justice John Roberts’s answer, for himself and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito, was no. (Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote a separate concurring opinion.) Invoking what he characterized as the nondiscrimination principle of Brown v. Board of Education—the unanimous 1954 ruling that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional3—Roberts wrote, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

To Breyer, writing for himself and Justices Ginsburg, John Paul Stevens, and David Souter, Roberts’s invocation of Brown was profoundly misleading. Parents Involved concerned plans by which the school systems in Seattle and in Louisville, Kentucky, striving to retain the hard-won gains of integration, sought to avoid school-by-school racial isolation by limiting the ability of students of any race to select or transfer into schools where their race was on the verge of predominating. While Roberts denounced this approach as an effort at “racial balance, pure and simple,” Breyer saw something categorically different. “The context here is one of racial limits that seek, not to keep the races apart, but to bring them together,” he wrote. “Indeed, it is a cruel distortion of history to compare Topeka, Kansas, in the 1950’s to Louisville and Seattle in the modern day.” Breyer warned that if school districts lost access to such tools, what lay ahead was “the de facto resegregation of America’s public schools.”

During its new term this fall, the Court will hear challenges to racially conscious admissions plans at Harvard and the University of North Carolina. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a scenario in which the universities emerge unscathed. At the high school level, a Virginia school district’s careful nonracial approach to admission at its prestigious limited-enrollment science and technology school is also being challenged in Coalition for TJ v. Fairfax County School Board, a case aimed at reaching the Supreme Court. The counterintuitive basis for that lawsuit is that the decision to drop a competitive district-wide, by-the-numbers admissions system in favor of one that guarantees places for the top eighth graders in more than two dozen middle schools was itself infused with race consciousness, to the detriment of Asian American applicants.

The Virginia school district modeled its geography-based approach on the “top 10 percent” system used by the University of Texas at Austin to achieve an automatic measure of diversity by offering places to the top students in all the state’s high schools. The Texas plan has narrowly survived two trips to the Supreme Court, most recently in 2016. But by the time the Virginia case reaches the Court’s docket, the precedents on which the school district relies may well have gone the way of Roe v. Wade. Another challenge to the Texas plan as unduly race-conscious is now making its way through the lower federal courts. Students for Fair Admissions, the organization bringing this case (it is also, notably, responsible for the Harvard and University of North Carolina cases), is clearly counting on the Supreme Court’s reconfiguration since it last upheld the Texas plan. Few would argue that its confidence is misplaced.

Advertisement

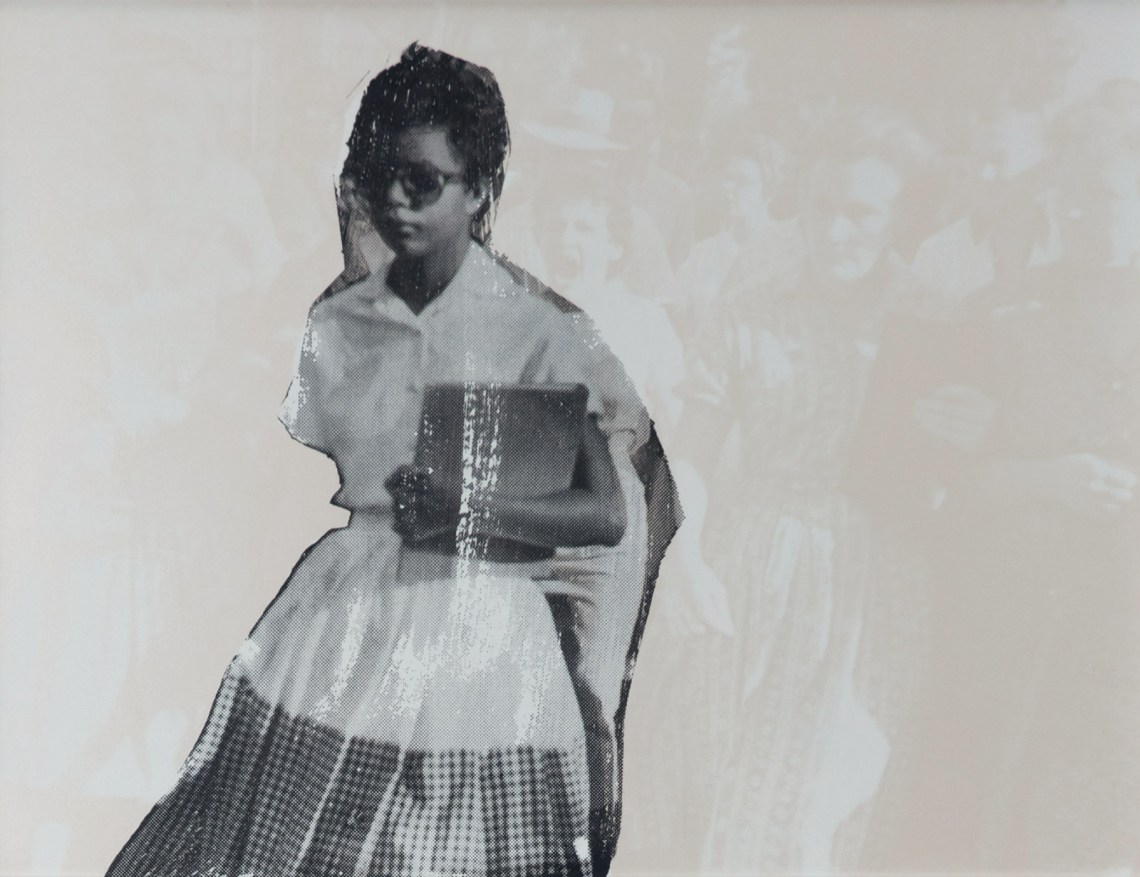

So now is a good time to revisit Breyer’s Parents Involved dissent for a refresher course on how the Supreme Court stood the principle of equality on its head. That is certainly one goal of his new book, Breaking the Promise of Brown. There is a second purpose as well, captured by the book’s subtitle, “The Resegregation of America’s Schools.” That purpose is to validate Breyer’s warning about the consequences of the false equivalence that Parents Involved exemplified—the notion that a “color-blind” Constitution admits of no difference between using race to segregate and using race to integrate.

From a high point of integration in 1988, when 37 percent of Black students attended majority-white schools, America’s public schools have resegregated to a startling degree. By 2018, that percentage had fallen by half. Such a drastic turnabout can’t be laid at the feet of any single Supreme Court opinion, of course. But that’s the point: while affirmative action at the university level still hangs by a thread in an increasingly hostile Court, the Court’s divestment from its integration project at the elementary and secondary level was decades old by the time of Parents Involved. So it’s possible to see that decision as having slammed shut a door, perhaps the final one.

At 127 pages, this is a very short book, although longer than The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics, which Breyer published last year. That book began as a lecture—hardly an unusual origin for an academic, as Breyer once was and is now again. Breaking the Promise of Brown consists of something more unusual: Breyer’s Parents Involved dissenting opinion. Printed in full, complete with the charts and graphs he included at the end under the label “Resegregation Trends,” the opinion takes up most of the book. The remainder consists of an introductory essay by Thiru Vignarajah, one of Breyer’s law clerks from that term.

To one degree or another, a Supreme Court opinion is almost always the product of a collaboration between justices and their clerks. It’s likely that Vignarajah, a former president of the Harvard Law Review who went on to become a federal prosecutor and deputy attorney general of Maryland, worked with Breyer on Parents Involved, even if only to the extent of compiling the social science research to which the opinion makes ample reference. The exact nature of the collaboration that produced this little book is undisclosed; although Vignarajah is identified as the sole author of the introduction, Breyer surely read and approved it.

The introduction provides useful context—that Breyeresque word—and is itself a powerful piece of advocacy, distilling for easy absorption the points that Breyer made at considerably greater length in the dissent. (The typeset version of the dissent as issued by the Court was seventy-seven pages long, nearly twice the length of the Roberts opinion.) Bestowing on Parents Involved the new name of “the resegregation cases” (the Louisville and Seattle cases began as two separate lawsuits), Vignarajah tracks the Court’s retreat from the desegregation orders that lower-court judges imposed frequently during the 1970s. He points out that even as the Court turned against these mandatory orders a decade later, it began at the same time to interfere with school systems and localities that embarked on such remedies voluntarily.

To follow the ensuing trajectory is to step through the looking glass: race-conscious remedies for segregation that were once mandatory became merely permissible before finally, after Parents Involved and other cases, becoming prohibited.

The distance the Court has traveled becomes startlingly obvious in a paragraph Vignarajah quotes from Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, a 1971 Supreme Court opinion that upheld a busing order in a North Carolina school district. The author was the conservative chief justice, Warren Burger, and the decision was unanimous:

School authorities are traditionally charged with broad power to formulate and implement educational policy and might well conclude, for example, that in order to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society each school should have a prescribed ratio of Negro to white students reflecting the proportion for the district as a whole. To do this as an educational policy is within the broad discretionary powers of school authorities.

Soon enough, the “broad discretionary powers” were no longer, in the Supreme Court’s view, the solution. They were the problem—a problem of constitutional dimension in the eyes of an increasingly conservative majority that began to strike down efforts by states and localities to address the systemic legacy of racial discrimination through such measures as hiring preferences and public contracting set-asides. Did the Court really know best? Vignarajah highlights Breyer’s lament toward the end of his Parents Involved dissent, a summons to the judicial humility of an earlier era:

Advertisement

I do not claim to know how best to stop harmful discrimination; how best to create a society that includes all Americans; how best to overcome our serious problems of increasing de facto segregation, troubled inner city schooling, and poverty correlated with race. But, as a judge, I do know that the Constitution does not authorize judges to dictate solutions to these problems. Rather, the Constitution creates a democratic political system through which the people themselves must together find answers. And it is for them to debate how best to educate the Nation’s children and how best to administer America’s schools to achieve that aim. The Court should leave them to their work.

What was “the promise of Brown” of the book’s title, the promise that Parents Involved broke? It was “the promise of true racial equality—not as a matter of fine words on paper, but as a matter of everyday life in the Nation’s cities and schools,” Breyer wrote. “It sought one law, one Nation, one people, not simply as a matter of legal principle but in terms of how we actually live.”

Throughout his twenty-eight years on the Court, up to and including the final days of his last term, Breyer insisted on the need to pay attention to consequences. In his view, the Constitution is a practical document designed to guide, not impede, a workable government. During his long tenure, he was known not for passion but for a cool intellectualism. But there was passion in his Parents Involved dissent. Its penultimate line warned, “This is a decision that the Court and the Nation will come to regret.” This book aims to show, years later, that he was right.

On one level, a dissent is a record of failure, a job left undone, a goal not achieved: the author has not managed through the force of reason to change minds. But for Urofsky in his book on Supreme Court dissents, a dissenting opinion is also part of the ongoing “constitutional dialogue” by which constitutional law is made and society itself is shaped. Charles Evans Hughes, who served as chief justice from 1930 to 1941, called dissent “an appeal to the brooding spirit of the law, to the intelligence of a future day.” A dissenting opinion may mark the majority’s handiwork as not only deeply contested, but vulnerable. It can rally the base and inspire like-minded lower-court judges to find creative workarounds to holdings of which they disapprove. Even if only by increments, it can move the law.

Until the early decades of the twentieth century, dissent on the Supreme Court was strongly disfavored. Nearly all decisions were unanimous under a “norm of acquiescence,” in Robert Post’s phrase, that was driven by the belief that dissenting opinions undermined the authority of the Court’s judgments. Justice Louis Brandeis wrote in 1932, “In most matters it is more important that the applicable rule of law be settled than that it be settled right.”

Of course, which “matters” were appropriate for Brandeis’s standard was open to dispute, and the norm began to break down. Scalia, a prolific and enthusiastic dissenter, wrote in 1998 that dissents can “augment rather than diminish the prestige of the Court.” More effectively than an “artificial unanimity,” he wrote, the existence of dissenting opinions makes clear that the Court’s decisions “are the product of independent and thoughtful minds, who try to persuade one another but do not simply ‘go along’ for some supposed ‘good of the institution.’”4

History may well vindicate Breyer’s Parents Involved dissent, a process this book aims to launch. But the current Court will not—and even if it did, the resegregation process is now so far along that it could be reversed only with dislocations on a scale that neither the Court nor the public would find acceptable.

I understand the choice to include only Breyer’s dissent in Breaking the Promise of Brown. After all, it tells the story he wants to tell, unchallenged and unadorned. But I think the book missed an opportunity. There were four other opinions in the case: Roberts’s for the plurality of four justices; a concurring opinion by Thomas; an opinion by Kennedy concurring only in the judgment while withholding his vote from Roberts’s opinion; and a short and powerful dissent by Stevens, then the longest-serving member of the Court. While Stevens signed Breyer’s dissent, he had something to say in addition. “It is my firm conviction,” Stevens wrote, “that no Member of the Court that I joined in 1975 would have agreed with today’s decision.”

Readers would benefit from having all the opinions between the same covers. The full decision is readily available on the Internet, and anyone wondering what drove Breyer to his emphatic dissent can simply download the whole thing. (Supreme Court decisions are in the public domain, and the publisher of Breyer’s book, Brookings Institution Press, notes that he will receive no royalties or other compensation.) The analytic weakness and rhetorical excess of Roberts’s opinion becomes evident in light of Kennedy’s explanation for why he couldn’t sign it.

During his time on the Court, Kennedy never voted to uphold a government program that counted people by race. So why did he refuse to sign Roberts’s opinion, thereby depriving the new chief justice (it was only Roberts’s second term, Kennedy’s twenty-first) of the ability to speak for a five-member majority?

Kennedy’s explanation was clear and precise. Roberts’s opinion, he wrote, “is too dismissive of the legitimate interest government has in ensuring all people have equal opportunity regardless of their race.” The opinion was “at least open to the interpretation that the Constitution requires school districts to ignore the problem of de facto resegregation in schooling,” he said, adding, “I cannot endorse that conclusion.” School districts should be encouraged to use such methods as resource allocation, recruitment, and strategic drawing of attendance zones—mechanisms that, while undertaken with awareness of race and racial consequences, “do not lead to different treatment based on a classification that tells each student he or she is to be defined by race.” Kennedy was scathing about Roberts’s line that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” It was “not sufficient to decide these cases,” he wrote. The problem “defies so easy a solution.” Martha Minow, in her 2010 book In Brown’s Wake, derided Roberts’s line as an “aphoristic reduction” of Brown itself.

Without having encountered Roberts’s aphorism in the text of his opinion, a reader of Breaking the Promise of Brown would have no context for Breyer’s sly footnote 164, in which he points out the origin of what he labels “the plurality’s slogan.” It turns out not to have been original to Roberts. Rather, the chief justice lifted it without attribution from a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Carlos Bea, a conservative who dissented from the decision that upheld the Seattle plan—and whose view Parents Involved vindicated. Breyer quotes from Bea’s dissent: “The way to end racial discrimination is to stop discriminating by race.”5

Perhaps Breyer derived some small satisfaction from unmasking the chief justice’s benign plagiarism. If so, it would likely have been the only source of pleasure at the end of a transformational Supreme Court term. In hindsight, we can easily see what Parents Involved portended, not only for America’s public schools but for the Supreme Court. Breyer surely understood this at the time, and it was that insight that gave his dissent its power. He knew that in December 2005, Sandra Day O’Connor’s last month as a justice, the Court had refused to hear an appeal challenging a student-assignment plan in Lynn, Massachusetts, very similar to those in Louisville and Seattle. The federal appeals court in Boston had upheld the plan, just as federal appeals courts had recently upheld the Louisville and Seattle ones. There was, in other words, no “conflict in the circuits” about the constitutionality of such measures, no disagreement that the Supreme Court needed to resolve.

Weeks later, the petitions challenging the Louisville and Seattle plans arrived at the Court. By the time the petitions were ready for the justices’ consideration, O’Connor was gone and her successor, Alito, was on the bench. In what was arguably the most important act of the reconfigured Roberts Court, and an early sign of what it would mean for Alito’s activism to replace O’Connor’s commitment to moderation, the justices accepted the two cases for decision the following term.

It was not only Parents Involved that marked the Court’s turn during the 2006–2007 term. With Alito in O’Connor’s place, the Court reversed course on the question of so-called partial-birth abortion, upholding a federal law that prohibited the procedure, even though it had invalidated an identical law in Nebraska just seven years before. And with Alito writing for a 5–4 majority in yet another case that term, the Court interpreted the federal law against pay discrimination so narrowly that Congress promptly repudiated the decision by enacting the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009.

“It is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much,” Breyer declared from the bench in summarizing his Parents Involved dissent. It was an extraordinary statement for a justice to make. The proceeding was not broadcast, and the courtroom audience was small, consisting mainly of members of the elite Supreme Court bar and the Court’s resident press corps. But it was an audience that Breyer surely knew was in a position to amplify his voice. His line about the “few” and the speed of change figured prominently in news accounts of the decision. People who heard or read those accounts scrambled to find it in the dissenting opinion’s many pages. It wasn’t there. It wasn’t, after all, part of a careful parsing and analysis of the case at hand. Breyer’s written opinion did that. This was something different. It was one man’s lament.

Since the line was not part of a published opinion, no subsequent opinion ever cited or repeated it. It lived on as oral tradition, lacking the official status that comes with publication in United States Reports, lacking everything but its essential truth. And then, on June 24 of this year, it surfaced. At the end of their joint opinion dissenting from the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Breyer and his two colleagues wrote, “One of us once said that ‘it is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much.’” There followed this addendum: “For all of us, in our time on this Court, that has never been more true than today.”

This Issue

October 6, 2022

The Slow-Motion Coup

Endless Summer

-

1

For more on their dissent from Dobbs, see David Cole, “Egregiously Wrong,” The New York Review, August 18, 2022; and Laurence H. Tribe, “Deconstructing Dobbs,” The New York Review, September 23, 2022. ↩

-

2

The late legal scholar Lani Guinier celebrated Breyer’s oral dissent as an example of “demosprudence,” which she defined as an appeal to the people as the ultimate lawmakers by “transforming an elite stage into a democratic agora.” See her “Foreword: Demosprudence Through Dissent,” Harvard Law Review, Vol. 122, No. 1 (November 2008). ↩

-

3

That there were no dissenting votes was “a central feature of Brown’s mythic status,” Justin Driver observed in The Schoolhouse Gate (Pantheon, 2018), his account of the Court’s role in American education. ↩

-

4

Antonin Scalia, “Dissents,” OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Fall 1998), p. 19. ↩

-

5

I discussed the origins of the line at some length in a 2007 law review article, “A Tale of Two Justices,” The Green Bag, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Autumn 2007), pp. 40–41. ↩