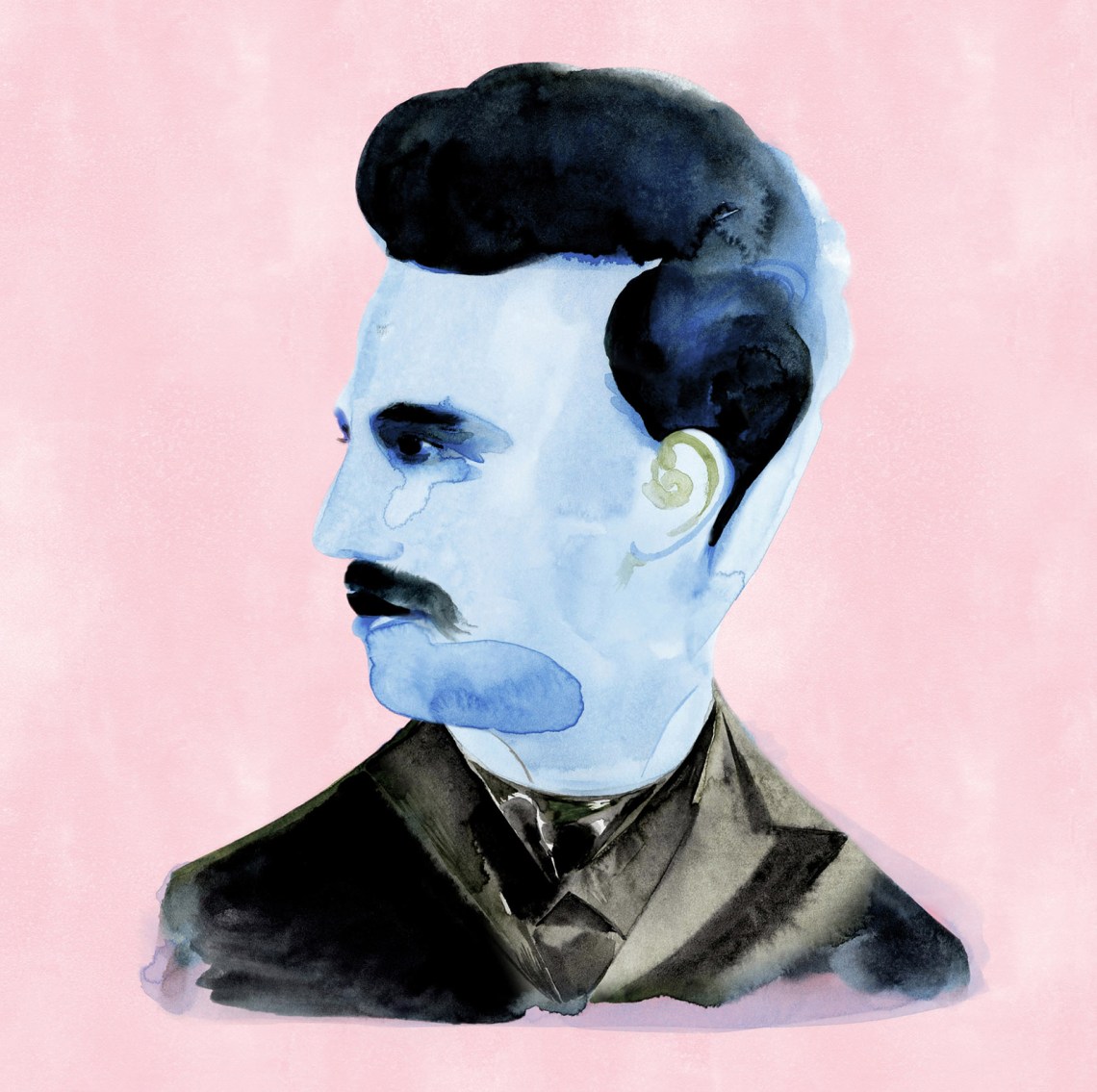

On the first page of her deeply perceptive and passionately argued study of Rainer Maria Rilke, mainly as a poet but also as a personality, Lesley Chamberlain admits that she is speaking symbolically in describing her subject as “the last inward man,” since there are some who “will always be attracted to the mystical and the metaphysical.” All the same, she is in no doubt that “the age of inwardness, the flowering of cultures in the West that were individualistic and reflective, has passed.” Many of us are apprehensive as to the direction taken in recent times by what used to be called “culture.” Few of us would be so brisk in announcing that the game is up.

A couple of pages later, however, Chamberlain relents so far as to admit that “Rilke gave, and still gives, a function for poetry to help any and all of us withstand the materialist–technological onslaught” of the modern age. The fervent Rilkeans of his day were mostly aristocrats and members of the haute bourgeoisie, but there were also some students and even workers who read him. Were they merely hankering after a lost, indeed an annihilated, world, the last flaring glory of which seemed to burn in the breast of their poet? Think not only of the debacle of Flanders but also the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871 and the Russian Revolution.1 The lamps were not just going out all over Europe, as the British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey famously remarked on the eve of World War I; they were going out everywhere, and in our own time more and more sources of illumination are being steadily extinguished.

Rilke had his moment, and it was a great one. When he died at the early age of fifty-one in 1926, everyone, Chamberlain assures us, was reading him. By “everyone” she means the everyones who counted, such as Virginia Woolf and André Gide, the art critic Meyer Schapiro, and the Austrian novelist Robert Musil. Quite a few lesser lights also must have been buying him, for in his mature years the poet was making good, or goodish, money from his publications.

A consistently steady earner was the at once wildly romantic and fiercely militaristic Lay of Cornet Christoph Rilke (1912). This unashamedly self-serving mini-epic in verse—part of its aim was to establish Rilke’s nebulous pretensions to an aristocratic heritage—had addressed directly the jingoistic peoples of the German-speaking world in the lead-up to the Great War and to the same, now bitterly resentful peoples after the catastrophic defeat of 1918 and the subsequent humiliations of the Versailles Treaty. But in Rilke’s pleasure garden, Cornet was a sport of nature. His real poetry was of another species altogether.

What place was there, in such a time, in such an aftertime, for a lyric poet of tender sensibilities and transcendent vision? Chamberlain writes:

[Rilke’s] reputation was at its height, early in the twentieth century, when the cultural momentum was suddenly intensely secular and political. The politically engaged future challenged what art should be. Rilke’s “angels” and “roses” suddenly seemed absurdly irrelevant.

In a post-Darwinian age, Rilke the unbeliever offered, Chamberlain writes, “the idea, or, rather, the feeling of God.” Which is not to say that he was a pantheist. He did not see God as immanent in nature; he took nature as itself the immanent god. And what of us, what is our task? Here we encounter one of Rilke’s central but most elusive concepts.

In the ninth and perhaps greatest of the Duino Elegies (1923), the poet begins by wondering why we have to be human and exist here at all, and at once provides a ringing answer to his own seemingly rhetorical question:

…because being here amounts to so much, because all

this Here and Now, so fleeting, seems to require us and strangely

concerns us. Us the most fleeting of all.

He goes on to lament the fact that everything, including us, will be on this earth once, and once only. Ah, yes, he says,

But this

having been once, though only once,

having been once on earth—can it ever be cancelled?

And there is more, much more, for us to do besides being here and bearing witness. “Praise the world to the Angel,” we are urged, “not the untellable.”

These things that live on departure

understand when you praise them: fleeting, they look for

rescue through something in us, the most fleeting of all….Earth, isn’t this just what you want: an invisible

re-arising in us? Is it not your dream

to be one day invisible? Earth! invisible!

What is your urgent command, if not transformation?2

Here is the essence of Rilke’s singular philosophy of life—and death, and the place of openness we enter by way of death. Our existence is a kind of Lebenstod, and it is only in the full, continuing, and accepting awareness of our predicament as creatures now living who one day will die that we have our authentic being in the world. No wonder the pre-war Heidegger read Rilke with such passion and insight. Chamberlain writes:

Advertisement

[Rilke] didn’t believe in another life in the beyond, but we can’t understand his poetry if we can’t grasp how important it was for him for life and death to be woven together and how, in a fundamental Christian sense, that thought did help him confront the rottenness inherent in human ways, and the futility of so many ill-housed lives.

The Last Inward Man is mainly an extended and always illuminating monograph on Rilke’s poetry; Chamberlain glances at the events of his life only when they impinge on or have relevance to his art. Numerous biographical studies of the poet have been written, but the definitive one surely is Ralph Freedman’s Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke (1996). Freedman knows the poetry as intimately and almost as insightfully as Chamberlain. As for Rilke the man, Chamberlain rises frequently to his defense, while Freedman gives us the goods. And the goods on Rilke are in most cases very bad. In the history of literature it would be hard to find a more thoroughgoing bounder who was also a great poet, though Byron, for instance, would rank highly on the lists of bounderdom.

Rilke was born in 1875 in Prague, the second city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, into a German-speaking family that claimed its origins among the warrior knights of Carinthia in the Middle Ages. From the start, Rilke considered himself an aristocrat, if not genuinely of the blood then certainly of the spirit. His birth was premature, and for some weeks it seemed the child might not survive. His father was first a soldier and then a railway official. His mother, Sophia, called Phia, came from a higher social level than that of her husband. “The geography of the world surrounding the young Rilke,” Freedman writes, “reflects in many important ways the topography of the future poet’s mind.” After the breakup of his parents’ marriage, the boy lived with his mother in undistinguished quarters just around the corner from the Herrengasse, the street of the gentry, where her family had a grand mansion. For the rest of his life, social climbing would be Rilke’s main form of exercise.

In the year before Rilke’s birth his mother had lost a week-old girl. As often in those days, the little boy who survived was burdened with the female-sounding names René Maria and dressed in skirts. For the rest of his life he felt strongly the pressure of the anima side of his nature, sometimes resenting it, sometimes prizing it, and always using it as a spur to poetry—not for nothing did W.H. Auden, with cruel wit, describe him as the greatest lesbian poet since Sappho.

The feminine streak, however marked, did not hamper him in his lifelong compulsive womanizing. In 1915, Chamberlain tells us, after yet another romantic entanglement had tied itself into an impossible knot, his most devoted patron, Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis, the chatelaine of Duino Castle near Trieste, where the Elegies were conceived, accused him of being “something between a big booby and an incorrigible Don Juan.”

In a prior scrape he had called for help to his first and longest-lasting love, Lou Salomé. This remarkable woman, a Russian-born writer and psychoanalyst, friend of Nietzsche and colleague of Freud, was thirty-six when she met the twenty-one-year-old Rilke. One of the first favors Salomé did for him was to make him change his name from René to the sturdier Rainer. He fell, or threw himself, in love with her, and immediately began bombarding her with youthfully passionate poems, some of which found their way into his early collections. These lines are from The Book of Hours (1905):

Break off my arms: I’ll hold you

using my heart just like using my fingers,

seize my heart and my brain still lingers,

and if you set my brain on fire,

I will carry you on my bloody pyre.3

As a young adult Rilke became involved with an artists’ colony in the village of Worpswede on the bleak Lüneburg Heath near the North Sea. There he encountered two young women with whom he formed a peculiar triangular relationship that lasted throughout their lives, though the life of one of them, the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, was lamentably short.4 The other woman was the sculptor Clara Westhoff, whom Rilke married, and who bore his only child, the sadly, indeed disgracefully, neglected Ruth.

This girl is one of the most fleeting and most pathetic figures in the poet’s life. He and Clara largely left her to be brought up by Clara’s parents. Rilke rarely saw or spoke to her, and seems for much of the time to have forgotten she existed. According to Freedman, when she became engaged, the poet informed her future husband that “the reason why Ruth had never been able to enjoy a normal family life had been her father’s commitment to his work, the result of ‘my life’s decisions…made long ago.’” Of course, he did not attend her marriage, and “postponed” sending the couple a gift—indefinitely, as it turned out.

Advertisement

Like so many of his other failures and betrayals in his dealings with human beings, even the ones he was closest to, his indifference to their needs and longings was explained as a necessary sacrifice to the demands of his work. One recalls Elizabeth Bishop writing to Robert Lowell about his unsparing use in The Dolphin of Elizabeth Hardwick’s anguished letters to him after he had left her for Caroline Blackwood: “But art just isn’t worth that much.” “Oh yes it is,” Rilke, along with Lowell, would have coolly responded.

Chamberlain tries her best, if not to exonerate Rilke, then to see the matter from his point of view, selfishly monocular though it was. After he had as good as abandoned his wife and child, Salomé urged Clara to set the police on him. In a letter to his mother, he acknowledged that “as a father I have been careless and inattentive”—which was putting it mildly—but insisted that he had only enough strength “for my work, and for the tasks and achievements that one way or another are connected with it.” Chamberlain goes on to cite the adverse judgments of John Berryman—“Rilke was a jerk”—and of the critic Michael Dirda, who considers him “one of the most repugnant human beings in literary history.” Putting the case for the defense, though in something of a non sequitur, is the novelist Nicole Krauss, quoted by Chamberlain: “Freed of the weight of wife and daughter, Rilke forced himself to work every day.” The weasel word there is “freed.” And there were very many days, even years, when Rilke hardly put pen to paper.

As a sponger (he regularly dipped into a fund that friends had set up for the education of his daughter) and lecher, he was in a class with Tartuffe. He never owned a dwelling place and lived on the kindness, or at least the sufferance, of others. He was shameless in his toadying to the moneyed and propertied among his acquaintances. There was hardly a Schloss or château in the Europe of his day whose visitors’ book did not have inscribed in it one of his prettily graved, cloying little thank-you verses. In his tailcoat and spats and white linen gloves he graced the salons of the leading hosts and hostesses—mostly the hostesses—of his time with tireless dedication, all the while complaining that all these many people and parties were keeping him from his task of making poetry.

Gratitude? Chamberlain writes: “He built his own castle and invited no one in.”

And then there were the girls. Let it simply be said that there were very many of them, and that he treated them all, without exception, abominably. Even the last serious love of his life, the artist Baladine Klossowska, mother of the painter Balthus and the writer Pierre Klossowski, and midwife to the later Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus (1923), was at the close dumped like a still-twitching sacrifice on the altar of his art. And it was an altar, and it was a sacrifice. The fact that his calling to the priesthood of poetry released him from many of the encumbrances of everyday life was, to his eye, incidental.

But Rilke’s unfeelingness ran deeper than mere selfishness. As Chamberlain points out, he had

a terrible flaw: his inability to love other human beings in the moment…. It is a truth about Rilke that he strained to reduce everything living to what was impersonal and inanimate. It might be stone, or plant. It might be a poem or painting. Not just something living and breathing, unless it was the universe itself.

As he said himself, “I have seen no one, but things, things: and it is ultimately through them that I have always composed my life.” This may sound like sterility, but it is not.

For Rilke, it is the artist’s task, indeed the task of any “living and breathing” human being, to absorb the realm of things and thereby transform it into something rich and strange, that is, into something even richer and stranger than it is in itself. It is this drive to defamiliarize the world and see it anew that for Chamberlain marks him as a modernist, along with Van Gogh and Joyce and Wittgenstein—and, we might add, Kafka. Gesang ist Dasein (Song is being), he declared in the third of the Sonnets to Orpheus; he might as easily have written, Sprache ist Dasein. In the Ninth Elegy he speculates:

Are we, perhaps, here just for saying: House,

Bridge, Fountain, Gate, Jug, Olive tree, Window,—

possibly: Pillar, Tower?….but for saying, remember,

oh, for such saying as never the things themselves

hoped so intensely to be.

As Chamberlain splendidly has it, “Human lives are led in the weighty and dazzling presence of things.”

Chamberlain sees Rilke as wrestling directly with the implications of the Darwinian revolution. At the turn of the twentieth century, after millennia of religious belief, it began suddenly to feel as if man was alone in the universe. Nature is lovely, nature is to be loved, but she is not the benign mother created by God to watch over us that previously she—it!—was taken to be. Rilke wrote: “It seems over and over that nature knows nothing of what we make of her and how we anxiously avail ourselves of a little part of her strength.”

The landscape is something alien for us, and we are terribly alone among the trees that blossom and the streams that pass. Alone with someone who has died we are nowhere near as exposed as we are alone with trees. For however mysterious death is, life is all the more so, a life that is not our life, a life that takes no part in ours, that celebrates its festivals without seeing us, and which we look upon with a certain discomfort, like guests who have turned up by accident and speak a different language.

Toward the end of his life Rilke settled in the tiny isolated tower of the Château du Muzot, in Switzerland, where he completed the Elegies, which constituted his life’s great work, and where also, astonishingly, in the space of a few weeks, he set down the two cycles of the Sonnets to Orpheus. He felt that these last poems were not so much composed as spoken through him: Ein Gott vermags, as one of the sonnets declares—“A god can do it.”

The story of Rilke’s last illness and death in the closing days of 1926 is shrouded in myth, unsurprisingly. Gathering roses for a visitor to Muzot, he pricked his finger badly on a thorn; the wound would not heal, and soon his entire arm was swollen; the doctors were called, and leukemia was diagnosed. It is a pretty if tragic account. However, the incident of the thorn took place the year before the fatal disease was finally identified. Truth or legend? Take your pick. What cannot be questioned are the pain and anguish that suffuse the astonishing last poem beginning, Komm du, du letzter, a direct address to his illness and a magnificent valediction to all he had known and treasured, which he wrote a mere fortnight before he died, in various forms of agony, yet praising to the end the things of this world, which, as the Ninth Elegy has it,

Want us to change them entirely, within our invisible hearts,

into—oh, endlessly—into ourselves! Whosoever we are.

“Erect no gravestone to his memory; just/let the rose blossom each year for his sake.” This is Rilke’s injunction in the Sonnets to Orpheus, speaking of the lost minstrel god. In The Last Inward Man Lesley Chamberlain erects a fitting monument to a transcendently great poet. For all her initial misgivings, she has no doubt of the continuing centrality of art and the powers of the imagination to our essential humanness:

[Rilke] was trying to find a new sensibility for the twentieth century, at a time when a certain style of philosophy had not yet made “the meaning of life” a naive question. His poems concern our gender and sexuality, our sense of what we ought to be doing with our lives, the possibility of the existence of God, the charmed kinship with animals which brings us such happiness, the importance of childhood, the attraction of the physical objects we make and buy and choose to live among, the landscapes we respond to, the books we read and the paintings in whose company we live. There is no object under Rilke’s gaze that resists transformation into a feature of a marvellous universe that envelops us in a world that might otherwise leave us restless and afraid.

That his character left much to be desired, and much to be deplored, cannot taint his achievement. If the cost of his living was high, the poetry he left behind is priceless. Rilke is great in his ability to dwell poetically in the heights and on wholly solid ground; his work is always at once angelic and mundane. Ein Gott vermags, yes; but so could a man.

This Issue

November 3, 2022

Gored in the Afternoon

The Illusion of the First Person

Reform or Abolish?

-

1

Not to mention, or at least only in a footnote, the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916, which some consider to have constituted the beginning of the end of the British Empire. ↩

-

2

Duino Elegies, translated by J.B. Leishman and Stephen Spender (Norton, 1939), pp. 73 and 77. Some readers will find that this version of the Elegies creaks a little. Stephen Mitchell’s translations of a very great deal of Rilke are wonderfully muscular and clear, and are by now almost the standard English versions. ↩

-

3

The majority of the translations in The Last Inward Man are by Chamberlain. Most are excellent, and all are ingenious. She emphasizes the importance Rilke attached to rhyme, and admits the difficulty of finding English rhymes to match the German ones. Sometimes her versions are a little contorted, but the contortions are those of a wonderfully gifted performer. ↩

-

4

Paula’s death was the inspiration for one of Rilke’s greatest but inexplicably disregarded works, the extended Requiem for a Friend. ↩