If President Joe Biden thinks that Rupert Murdoch is “the most dangerous man in the world,”* President Franklin Roosevelt felt much the same about “the McCormick/Patterson newspaper Axis.” The Murdochs of their day were Colonel Robert McCormick and the siblings Joseph Patterson and Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson, a newspaper-owning cousinhood united by hatred of Roosevelt. Their grandfather Joseph Medill had co-owned the Chicago Tribune, which eventually passed to his grandson McCormick, while another grandson, Joseph Patterson, founded the New York Daily News. The “Axis” might have extended to William Randolph Hearst, whose huge newspaper empire included the morning Washington Herald and the evening Washington Times. He refused to sell them to Cissy Patterson when she first approached him, but instead made her editor of both in 1930—the first American woman in such a position—and in 1939 he sold her the two papers, which she merged into the Times-Herald.

They had their counterparts across the Atlantic. “Beethameer, Beethameer, bully of Britain,/With your face as fat as a farmer’s bum” was Auden’s robust line conflating two rogues, Lord Beaverbrook and Lord Rothermere. The high-minded English press had been revolutionized in 1896 by the arrival of The Daily Mail, cheap, demagogic, jingoistic, and soon outselling every other paper. It made the fortune of its creator, Alfred Harmsworth, whose principle was that “the British people relish a good hero and a good hate.” In the same brisk manner he reputedly also said, “When I want a peerage I’ll buy one like an honest man,” and so he did, to become Viscount Northcliffe. Before long he owned The Times as well as the Mail, much as Murdoch now owns The Times as well as the Sun, and had been joined in the House of Lords by his brother Harold, Viscount Rothermere, and by the most lurid adventurer of all, Max Aitken, Baron Beaverbrook.

Aitken made his first fortune in Canada while still in his twenties by way of overvaluation of stocks, insider trading, and fraudulent audits disreputable even by the standards of a laxer age. He left for England in a hurry, and with astonishing speed bought both a seat in Parliament and a knighthood at thirty-two, a peerage at thirty-seven (despite the objections of King George V), and control of the Daily Express, an ailing paper that he transformed.

In the first half of the last century the popular press enjoyed a position never known before or since. Other mass media had sprung up, but radio in America meant a multiplicity of stations large and small, mostly playing music, and in England it meant the BBC, whose mission, in the words of its stern Calvinist director-general Sir John Reith, was to “inform, educate, and entertain,” very much in that order, while shying away from political controversy. Television was in its experimental infancy, while the movies also avoided political controversy in the Western democracies, unlike in the Russian and German despotisms.

That left the field open to the press, whose involvement in peace and war is the subject of two new books. In The Newspaper Axis: Six Press Barons Who Enabled Hitler, Kathryn S. Olmsted claims that these monstrous moguls exercised a clear and malign influence on American and British policy, and that their desire not to “confront the fascist dictators made a war against fascism both more likely and more difficult to win,” while Alexander G. Lovelace’s theme in The Media Offensive is summed up in his subtitle, “How the Press and Public Opinion Shaped Allied Strategy During World War II.” Both books are informative and stimulating; whether they succeed in making their respective cases is another matter.

Having beaten the patriotic drum before 1914, Northcliffe and the Mail took the most bellicose line once war came. By late 1917 he was publicly criticizing the conduct of the war in the pages of his Times, which prompted the great Liberal editor A.G. Gardiner to say, “The democracy, whose bulwark is Parliament, has been unseated, and mobocracy, whose dictator is Lord Northcliffe, is in power.” In 1922 Northcliffe died insane, his title dying with him since he had no children by his wife (although several by mistresses), and so The Daily Mail passed to his brother Rothermere, whose descendants own it to this day, and to this day are embarrassed by his memory. In one quaint episode Rothermere took up the cause of undoing the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, which had brutally stripped the Kingdom of Hungary of two thirds of its territory, and was offered the Hungarian throne in return. Rothermere was then bewitched by another national movement. At Christmas 1934 he told readers of the Mail about a great leader who had “given Germany a new soul.” This adulation of Hitler continued: Rothermere claimed that he had seen “merry and festive parties of German Jews who showed no symptoms of insecurity or suffering,” and that anyway Germany needed to control “Israelites of international attachments.” Before long he was cheering Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists with his headline “Hurrah for the Blackshirts!”

Advertisement

Rather than open admiration for the dictators, Beaverbrook expressed a general contempt for Europe: “I don’t speak their languages. I don’t want to. I don’t know their politicians. I don’t like them. I don’t want alliances with European states.” In 1933 he wrote, “The policy for Britain is plain: no more truck with the foreigners.” After the Munich agreement in September 1938, the front-page skyline read, “The Daily Express declares that Britain will not be involved in a European war this year, or next year either.” As late as August 7, 1939, less than four weeks before Great Britain declared war, the front page shouted “NO WAR THIS YEAR,” which achieved further infamy in the 1942 patriotic film In Which We Serve: as the destroyer HMS Torrin puts to sea, a copy of the Express with that headline is seen floating in mucky dockside water.

Meanwhile those American papers owned by the “Axis” continued to denounce Roosevelt and any hint that the United States might be moving toward another war. McCormick was xenophobic in general and violently Anglophobic in particular, while the Daily News boasted, “You bet we’re an isolationist paper.” Olmsted also shows the degree of anti-Semitism still to be found in mainstream American newspapers in the 1930s and early 1940s. McCormick instructed the Tribune to identify Jews—“David K. Niles (whose real name is Nayhus)”; “[Walter] Winchell’s real name is Lipschitz”—while Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter was “the dwarflike Vienna-born former Harvard law professor.” The Tribune employed Donald Day as a foreign correspondent even as his Nazi sympathies became undisguised: in October 1941 he wrote to McCormick that the Germans would disrespect Americans “so long as our foreign policy is being largely directed by the Red Sea Pedestrians.”

More remarkable still was the anti-Semitism of the New York Daily News—a paper with a huge circulation in a city in which Jews made up around a quarter of the population—which led Jewish groups to organize a boycott. Protesters handed out cards that read: “I am doing my bit by not buying the Daily News. They are very unfair to the Jews.” Patterson retorted that his newspaper was merely “against our entering the war and sending another expeditionary force to Europe, Asia or Africa. That is not anti-Semitism.” In England Rothermere chimed in, and so did his rival and ally. “I estimate that one-third of the circulation of the Daily Telegraph is Jewish,” Beaverbrook told the American publisher Frank Gannett. “The Daily Mirror may be owned by Jews. The Daily Herald is owned by Jews. And the News-Chronicle should really be the Jews-Chronicle.” He insisted that the British Empire “exists for the British Race” and claimed, like Rothermere, that stories of the persecution of Jews in Germany were exaggerated. Olmsted might have added that when a boycott of German goods was proposed, the front page of the Daily Express announced that “Judea Declares War on Germany.”

This repellent story is vigorously recounted in The Newspaper Axis. The problem comes with Olmsted’s claims about the power of the press. She has no difficulty showing what a ghastly crew Hearst, McCormick, and the Pattersons were, as well as Beaverbrook and Rothermere, but she fails to demonstrate that they wielded great influence, since the evidence is to the contrary. For years on end the American press barons ferociously savaged Roosevelt. And with what result? In late 1936 P.G. Wodehouse was a highly paid if unenthusiastic screenwriter living in Beverly Hills. As the royal crisis loomed in London, Hearst’s papers noisily demanded that King Edward VIII be allowed to marry Wallis Simpson and she to become queen. After Edward abdicated in December, Wodehouse went to the movies, and when

Mrs Simpson came on the newsreel there wasn’t a sound…It shows once more how futile the Hearst papers are when it comes to influencing the public. He roasted Roosevelt day after day for months, and look what he done!

What “he done” was to win the second of four presidential elections by the largest popular-vote margin in more than a hundred years, carrying forty-six of forty-eight states. As Wodehouse added shrewdly, “What people buy the Hearst papers for is the comic strips.”

Even so, the Roosevelt administration was still obsessed by the hostile press. Harold Ickes was secretary of the interior for thirteen years and was responsible for putting much of the New Deal into practice, but in 1939 he found time to write America’s House of Lords, a sprightly philippic denouncing the newspaper “Axis,” full of lurid detail about bias, suppression, and distortion, which showed that Ickes was a pretty good muckraking journalist himself. He cleverly quoted the lines, “I rather think that the influence of the American press is on the whole declining. This, I believe, is because so many newspapers are owned or influenced by reactionary interests” indifferent to “the welfare of the public”—spoken by none other than William Randolph Hearst himself in 1924.

Advertisement

In England the limits of the press lords’ power had already been dramatically demonstrated by their one attempt to unseat a party leader. In 1930, while Stanley Baldwin led the Tories in opposition, “Beethameer” launched a concerted attack on him, even running parliamentary candidates. He saw them off in a single speech, and with a single phrase (provided by his cousin Rudyard Kipling), denouncing the press lords for seeking “power without responsibility—the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages.” Whatever his other difficulties, Baldwin was never again troubled by “Lord Copper and Lord Zinc,” as the two ogres of Fleet Street became in Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop.

What frustrated critics of the right-wing press are reluctant to concede is the extent to which popular papers become popular by reflecting opinion rather than directing it. From Northcliffe and Hearst on, the press lords have succeeded by tapping into sentiment—often ugly enough—that was already there. The Daily Mail beat the drum for the Boer War and then the Great War, but it didn’t cause them. In Citizen Kane, a movie plainly inspired by Hearst, there is an episode supposedly taken from Hearst’s life, when Kane sends a correspondent to Cuba to foment the 1898 Spanish-American War. The correspondent cables, “Could send you prose poems about scenery…there is no war in Cuba,” to which Kane replies, “You provide the prose poems—I’ll provide the war.” As it happens, those last words were exactly the sense that Tony Blair conveyed to John Scarlett, chairman of the British Joint Intelligence Committee, twenty years ago. Scarlett duly provided the prose poems in the form of distorted or exaggerated intelligence, and Blair provided the Iraq War, or the British contribution to it. But again, although the London press allowed itself to be manipulated by Blair, and although Murdoch warmly supported that disastrous enterprise, he didn’t start it.

Persisting with her theme, Olmsted writes that “British public opinion was, of course, partly shaped by one of Britain’s best-selling newspapers, the Daily Express.” But was it? She quotes Ernest Bevin, the great Labour politician: “I object to the country being ruled from Fleet Street, however big the circulation, instead of from Parliament.” That was at the time of the 1945 general election, when almost every important British newspaper apart from the Daily Mirror supported Churchill and the Tories and roasted Labour, as Wodehouse might have said, with Beaverbrook’s Express doing so in poisonous fashion. After Churchill’s outrageous radio broadcast warning that a Labour government might mean “some sort of Gestapo,” the front-page headline in the Express read “Gestapo in Britain If Labour Win.” That evening Clement Attlee, the Labour leader, broadcast a masterly reply, in which he said, “The voice we heard last night was that of Mr. Churchill, but the mind was that of Lord Beaverbrook.” Within weeks Labour had won one of the greatest landslide victories in British electoral history. It’s hard to see much “shaping” there.

If, as Olmsted writes, “the conservative British and American media titans had achieved little in their efforts to influence domestic policies before 1937” (or after 1937 either, she could have added), “in the late 1930s the Nazis’ territorial demands roused them to fight for their preferred foreign policy,” by which she means encouraging the American public to support isolationism and the British to favor appeasement. This claim requires still more ingenuity. In the 1930s most British people didn’t want another war twenty years after one in which nearly a million of their young men had been killed. They were perplexed by the rise of Hitler and how to deal with him—whether by firm resistance or by the conciliation known as appeasement—which was just as much a conundrum for the left as for the Tories.

“The leaders of the Labour Party,” Olmsted writes, “decided by the mid-1930s to support British rearmament.” No they didn’t. From 1932 until 1935, Labour was led by George Lansbury, a much-loved but ineffectual socialist and pacifist, while the broader left parroted the slogan “Against fascism and war.” At the 1935 party conference Lansbury was brutally attacked for “hawking your conscience” by Bevin, one of the few Labour politicians who tried to persuade the left that being against fascism might mean being for war. Lansbury was replaced as party leader by Attlee, a former infantry officer, but even then Labour continued to vote in the House of Commons against the government’s annual armaments estimates until 1937, when it began merely to abstain.

And no cabal of press owners was needed to dictate American opinion about war and peace. From the Armistice in November 1918 until Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the American people were united in their determination not to enter another war, as survey after survey showed. One found that a majority didn’t want to fight against foreign tyrants, another that a majority regretted having taken part in the Great War, although American casualties had been trivial by European standards. This sentiment was reflected rather than dictated by the “Axis.”

The collapse of what was left of Czechoslovakia and Hitler’s entry into Prague in March 1939 persuaded the British at last that he couldn’t be stopped by concessions, and when he invaded Poland in September Neville Chamberlain took Great Britain to war, whatever Beaverbrook and Rothermere wanted. The United States remained neutral for more than two years, while the “Axis” hysterically denounced Lend-Lease as part of a conspiracy to take the country to war, even though Roosevelt insisted, on the eve of his third election victory in October 1940, “I shall say it again and again and again, your boys are not going to be sent into foreign wars.” He was as good as his word until fourteen months later, when the decision was taken out of his hands after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and Hitler declared war on the United States.

Here is where Lovelace takes up the story in The Media Offensive. His case is that the media, or relations between the media and political and military leaders, played a vital part in that war. His short book is filled with fascinating information, but he tends to confuse two things. If the American and British press had shown the limits of their power in the 1930s by failing to damage Roosevelt or prevent war, then the wartime story was not one of media power but of collusion. The power of the press to direct the course of events may be illusory, but there is nothing mythical in the close, even symbiotic, relationship between media and politics.

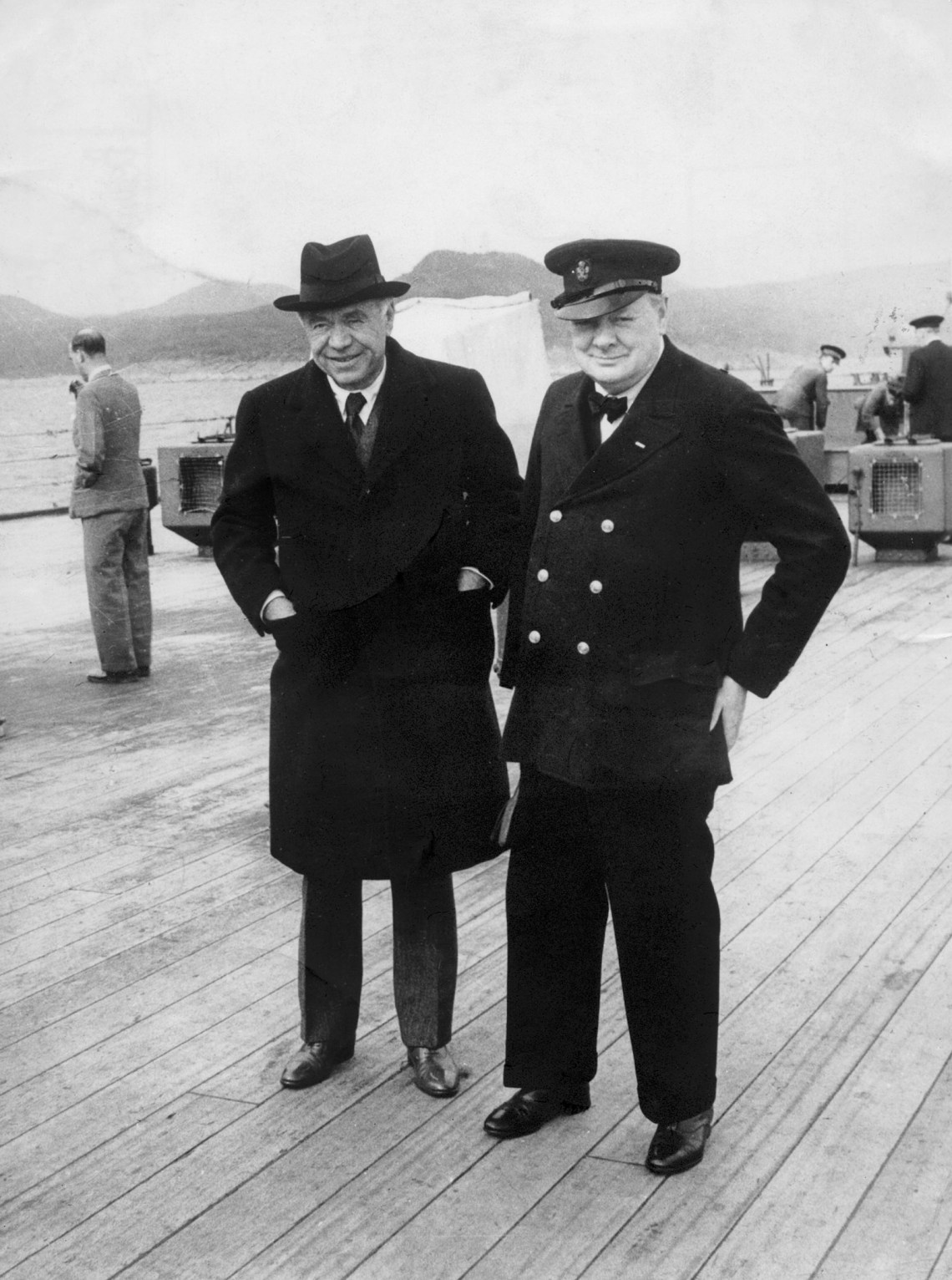

In England this relationship had long been more intimate than in America. Northcliffe’s Times supported the intrigue that brought David Lloyd George to power in 1916, and Lloyd George himself later even wondered whether he might become editor of The Times when he left Downing Street. Churchill was a journalist before he entered politics, and he took a keen interest in the press, inspecting the first editions late every night to see what the “calumnists or columnists,” in his phrase, were saying about him. He would have understood Lovelace’s claim that “what truly made World War II a media war was the importance the military placed on the press and public opinion as weapons for total war,” though that was not really new: it was Napoleon who said that “the printing press is an arsenal.”

A drafted peoples’ army, or levée en masse, as it would be called, had won the Battle of Valmy for the French revolutionaries many years before ardent national sentiment reached a climax in the Great War, but was discredited by the mud and blood of Verdun and Passchendaele. By the 1940s the armies of the Western democracies were manned by citizen-soldiers who could read, write, and vote, and who had rights as well as duties. All the campaigns fought by these armies were conditioned by their leaders’ knowledge that the carnage of the Western Front could never be endured again, and that casualties must be limited. This time, commanders as well as politicians not only knew that they required popular support but became masters of publicity and self-promotion. Churchill, no mean self-publicist himself, often saw the war in terms of dramatic gestures.

As soon as the United States entered the war, new disputes arose. Churchill has been lauded by his votaries for having persuaded Roosevelt to follow a “Germany first” policy, but there is less to this than meets the eye. “Japan first” had an eloquent advocate in General Douglas MacArthur, the most brilliant self-publicist of all, whatever he may have been as a strategist. Having been driven out of the Philippines, he insisted that its reconquest was the first priority. This never made much strategic sense and conflicted with the main American strategy of a direct westward thrust across the Pacific toward Taiwan, to cut off Japan from its conquests in Southeast Asia with their precious resources of oil and rubber.

In the event, the Americans mounted campaigns both across the Atlantic and across the Pacific and, since one of the most important consequences of that war was the explosive transformation of the American industrial economy, they could afford to. But MacArthur wasn’t preaching in a void. A poll in April 1942 showed that 62 percent of Americans thought the country should focus on Japan first. Roosevelt’s adviser Harry Hopkins had admitted the month before that “the concentration of attention on Pacific fighting is reflected by an increased public disposition to regard Japan either as our prime enemy or as equal in importance with Germany.” As late as early 1945 Dwight Macdonald observed, “Not the least ironical aspect of this most ironical of wars” was that “the war in the Pacific has always been more popular with all classes of Americans than the war in Europe.”

When the Americans did cross the Atlantic in November 1942, it turned out to be not Germany first but Vichy France first as the GIs landed in French North Africa. The Americans were and remained suspicious of being dragged into an irrelevant campaign whose purpose, they suspected, was as much to shore up British imperial interests in the Mediterranean as to defeat Germany. Having accepted that American troops needed to be seen in action across the Atlantic, Roosevelt put his hands together as if in prayer and said to General George Marshall, “Please make it before Election Day,” but the exigencies of war meant that the “Torch” landings in Morocco and Algeria didn’t take place until days after the midterms, in which the Republicans made significant gains.

Before that, in April and little more than four months after Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt authorized the bombing raid on Tokyo led by Colonel James Doolittle, which had no military purpose at all but was a statement, or a stunt. Lovelace might have compared that operation with another such stunt six weeks later, the thousand-bomber raid on the cathedral city of Cologne. It was planned by one more master of publicity, Arthur Harris, recently appointed by Churchill to lead Bomber Command. Roosevelt and his senior colleagues were still burdened by the cult of MacArthur. One newspaper suggested that the general’s face should be added to Mount Rushmore, and by 1944 some Republicans, egged on by McCormick and Henry Luce, talked about drafting him to run for the White House.

When American troops at last encountered the Wehrmacht in Tunisia, they joined hands with the British Eighth Army, led by General Bernard Montgomery, another man who knew how to butter up the press. As Frank Kluckhohn of The New York Times privately recorded, there was “much bitter feeling between Americans and British at the front.” This would be a persistent theme in the Italian campaign and then in Northern Europe as well, with bitterness exacerbated by the fact that the generals were such a collection of prima donnas. Montgomery was matched by the American Mark Clark, who had a public relations team of fifty men, and “the flamboyant, gun-toting [George] Patton, one of the most aggressive and hell-for-leather generals in the American Army,” as the Times described him, or as another said, someone who “Can Outshoot, Outfight, Outcuss and Outsmart Any Man in His Tank Outfit.”

Without doubt Clark allowed headlines, or just vanity, to affect his tactical judgment. “He wanted Rome and he wanted it for publicity reasons,” Lovelace writes, or as Clark himself said, “It was essential for various reasons—mostly political and psychological—that the Fifth Army capture Rome prior to the invasion of France.” So it did, just: Clark entered Rome on June 5, “as in a Roman triumph of old,” and was quite forgotten the next day when the Allies landed in Normandy. The campaign that began on D-Day saw yet more squabbles conducted through the press, although here again Lovelace confuses what he considers media power with public sentiment. Once V1 “doodlebugs” began hitting London only days after D-Day, it was the urgent wish of the Churchill government—and all Londoners—that their launching sites in northeastern France be overrun. So it was again with the first V2 supersonic rockets in September. As Montgomery wrote after the war, “That settled the direction of the thrust line of my operation.” And so he began planning his ill-considered and disastrous operation to seize Arnhem by airborne landings, which made little sense for that purpose, since Arnhem is seventy miles east of The Hague, from whose environs the rockets were launched.

One man who emerges with credit from this story is General Dwight Eisenhower, who wasn’t a strategist of genius and didn’t pretend to be but who calmly held together his team of squabbling egomaniacs. At the end he refused to make a rapid advance on Berlin or risk American lives for the purpose of striking attitudes and grabbing headlines, since he knew that the Allies had decided at Yalta how Germany would be divided for occupation, and that Berlin was well within the Russian zone.

“In the last analysis,” Eisenhower wrote, “no battles are won with headlines, although I appreciate that wars are conducted by public opinion.” So are political wars, and culture wars too. Headlines in Beethameer’s papers didn’t stop the British going to war in 1939 or Labour winning in 1945, while events overwhelmed the isolationist “Axis” papers in America. Likewise, Murdoch may at one time have had a knack for backing winners, but he has not dictated the course of British politics any more than Fox News has stopped the Democrats winning the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections. Politicians who blame their setbacks on the media should look harder at themselves.

This Issue

November 3, 2022

Gored in the Afternoon

The Illusion of the First Person

Reform or Abolish?

-

*

Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns, This Will Not Pass: Trump, Biden, and the Battle for America’s Future (Simon and Schuster, 2022), p. 354. ↩