In 1901, at the age of forty, the writer Rabindranath Tagore founded a small school at Santiniketan, in a rural part of Bengal about a hundred miles north of Calcutta. Twenty years later he added a university alongside it—Visva-Bharati, whose name joined together the Sanskrit words for world and wisdom and whose motto was “Where the whole world meets in one nest.” The educational outlook of these joint institutions was boldly experimental. They were coeducational. There was no physical punishment and little formal discipline. Classes were held outside, under the trees. Fine arts, music, sports, and drama were highly regarded, exams and formal results largely disdained. Teachers and students mingled freely outside their lessons. The overriding aim was to encourage the students’ imagination and freedom of thought and to inculcate in them an appreciation of the world’s (and India’s) great intellectual and cultural diversity. To this end, the curriculum ranged very widely, not just across the wealth of Indian history, art, and literature but with equal attention to the cultures of the West, Africa, Latin America, and other parts of Asia.

Tagore’s vision reflected his dissatisfaction with conventional schooling as well as his cosmopolitan upbringing. He had never himself managed to attend any school for very long, either in India or in England, to which he’d traveled as a teenager. In Brighton he soon dropped out of the public school selected for him; in London he spent only a few months as a student at University College London; at Presidency College in Calcutta he lasted an entire day. Instead he’d been educated in Sanskrit, English, music, philosophy, and other subjects mainly by private tutors and his talented elder brothers and sisters, several of whom were noted Bengali authors, composers, patriots, and intellectuals.

This bespoke, multicultural education had been possible not just because Tagore was his parents’ fourteenth child, but because he had been born into one of the leading dynasties of Bengal. At the end of the seventeenth century, his ancestors had become successful brokers to the East India Company. As its fortunes rose, so did theirs. By the nineteenth century, they were the Medici of Calcutta. Rabindranath’s grandfather Dwarkanath Tagore had been a fabulously wealthy merchant, philanthropist, and social reformer who dazzled European society, was entertained by Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace, and was eulogized as the greatest Indian of his time.

Rabindranath founded his school and university on a large estate that he inherited from his father, but running them was expensive. They were always short of money. Over the remaining forty years of his life, as he crisscrossed every continent, raising funds for them was one of his main preoccupations. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913, becoming the first Asian laureate, he used the money to improve facilities at Santiniketan. When the news arrived, it is said, he was stuck in a committee meeting, worrying about how to fund a new sewage system for the school buildings. On reading the telegram from Stockholm, he dryly announced, “Money for the drains has just been found!”

The award transformed his life, catapulting him to global fame. The young English poet Wilfred Owen copied Tagore’s poems in a notebook that he carried with him into the trenches of World War I. Bidding farewell to his family for the last time before his fatal return to the battlefield in the summer of 1918, he quoted one of his favorite passages from them: “When I go from hence, let this be my parting word,/That what I have seen is unsurpassable…”

In 1915 Tagore was knighted by the British government. Four years later, in protest at the brutal British massacre of hundreds of unarmed civilians in Amritsar, he renounced the honor, wishing instead, he said, “to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.” By this time he was already a prominent anti-imperialist and internationalist, a critic of British rule, and a fierce advocate of unity between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi, his friend, called him the “Great Sentinel” of Indian nationalism.

After the Western adulation came the backlash. Especially after his death in 1941, foreign views of Tagore all too often Orientalized and dismissed him as nothing more than an Eastern sage with a nebulous spiritual message. By the 1960s Bertrand Russell, despite having met him several times, could recall no more than “mystic views” and “vague nonsense.” But this was an unfair caricature that overlooked Tagore’s lifelong commitment to scientific and technological progress and to reasoned argument as the basis of all knowledge—a rationalist stance that had put him at odds with Gandhi more than once during the 1930s.1

Some of the central themes of Tagore’s worldview—East and West, household and nation, truth and illusion, religion and nationalism, reason versus tradition, the roles of men and women, freedom of action—can be glimpsed in his great novel Ghare Baire (1916; translated into English in 1919 as The Home and the World). They also suffused his educational philosophy, which eschewed textbook learning in favor of an antisectarian, internationalist spirit of free, reasoned inquiry and practical social progress (for example, through the educational uplift of women and of the rural poor, for whom he founded a separate school and clinic on his estate). “The main object of teaching,” he urged, “is not to explain meanings, but to knock at the door of the mind.”2

Advertisement

To bring this vision to life at Santiniketan, he gathered around him a group of equally committed teachers, artists, and social reformers. One of them was Kshiti Mohan Sen, a great liberal scholar of Sanskrit and Pali, Indian history, and folk songs, who joined Santiniketan in 1908 at Tagore’s urging and soon became his close friend and associate. Kshiti Mohan, though born into a conservative Hindu family, had become a follower of the ecumenical teachings of the fifteenth-century Indian mystic Kabir, which combined Muslim and Hindu ideas and literary traditions. He was captivated by Sufi poetry and music, learned Persian, and published in Bengali, Hindi, and Gujarati. The idea that India’s cultures, peoples, and religions had throughout their long history always been connected and intertwined to their mutual benefit was as central to his scholarship as to his progressive politics. His wife, Kiranbala Sen (a common surname in Bengal), was an accomplished painter and midwife. Their daughter Amita attended Santiniketan, learned judo alongside the boys, and went on to play the lead in Calcutta in several of Tagore’s celebrated dance dramas, at a time when it was still highly controversial for women of her class to appear onstage.

When Amita’s marriage was arranged, she moved to Dhaka, in eastern Bengal, where the family of her husband, Ashutosh Sen, were from, and where he was a professor of chemistry at the university. But in 1933, following Bengali custom, she came back home to Santiniketan to give birth to her first child. Her mother helped deliver the baby. Ever the creative, progressive spirit, Tagore urged his friends to eschew a traditional name for the infant boy and coined a new one, playing on a Sanskrit word for death: “Amartya,” meaning immortal.

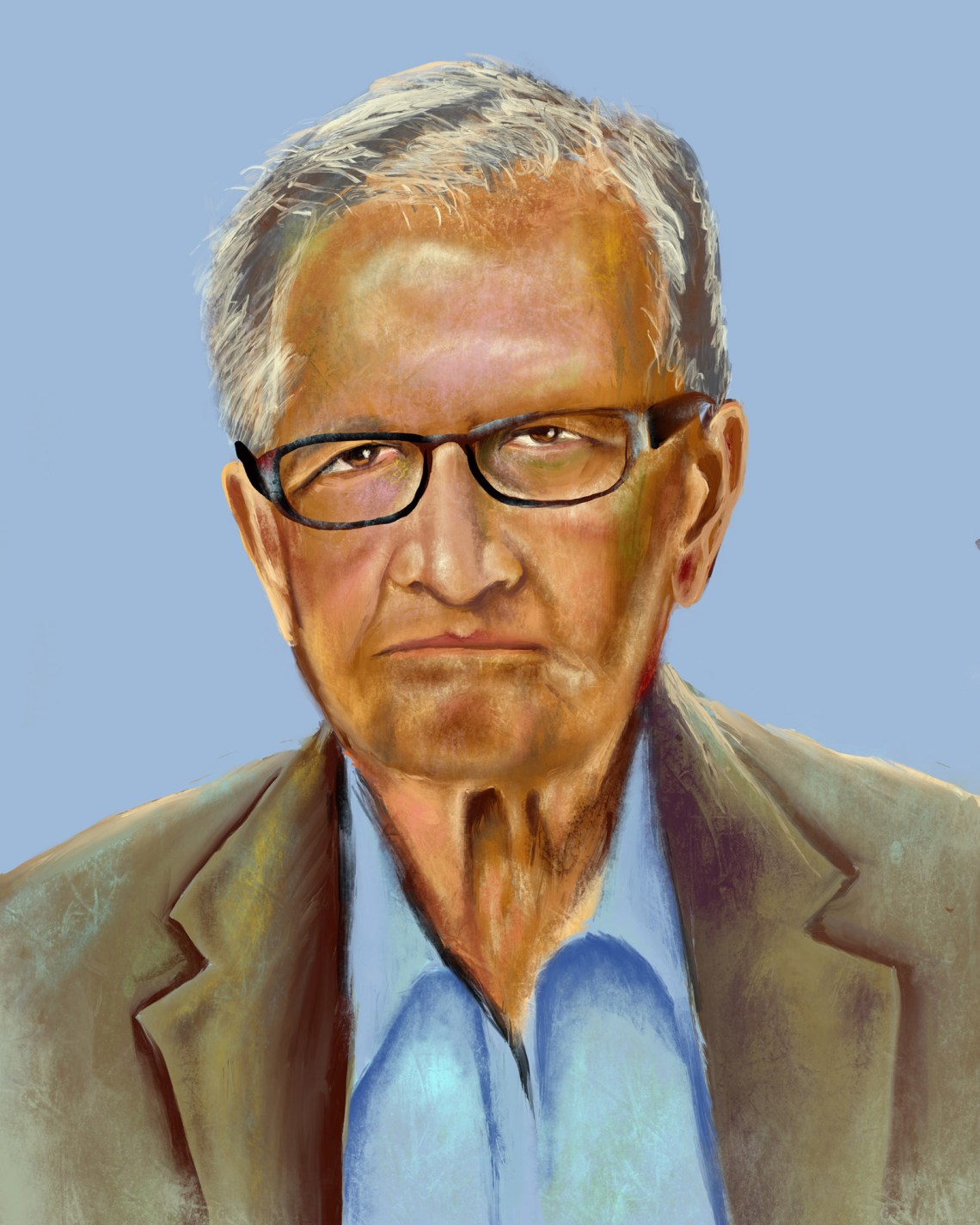

Some children might find it hard to live up to such portentous billing. But it turned out to be an apt name, in more than one sense. Amartya Sen is now almost ninety and one of the most celebrated and influential thinkers of our time. As a Nobel Prize–winning economist and pathbreaking moral philosopher, his scholarship has had a global influence on how academics and policymakers conceive of and address an entire range of fundamental problems, including the cause and prevention of famines, human well-being and development, poverty, welfare, social choice, the status of women, and definitions of justice. He has also always been an elegant and productive public writer and intellectual. Thirty-five years ago, in these pages, an admiring English colleague noted that Sen was “remarkably prolific and seems to have sped up at just the age when other people begin to relax.”3 That is still true.

In his writings Sen has often referred to events from his youth and connected them to his scholarly work. His elegiac memoir, Home in the World, expands these reflections into a moving and fascinating account of his much-traveled, multicultural childhood, education, and early academic career. Its title echoes that of Tagore’s novel, in tribute to the great poet’s lasting personal and intellectual influence. But it also is meant literally. From infancy, Sen’s life has been peripatetic, and he has managed to feel at home in many different places. By the age of ten, those already included Dhaka; Mandalay in Burma, where he lived with his parents between the ages of three and six; Calcutta, where many of his relatives were from; his family’s ancestral village of Matto in rural Bengal, where he spent many happy holidays; and Santiniketan, where he lived with his grandparents from the age of seven while attending Tagore’s school.

This lifestyle reflected both the size and warmth of Sen’s large extended family and their relative wealth and status among the cultural and educational elite of Bengal. Home in the World deftly conjures what it was like to grow up in this cosseted and endlessly stimulating environment. Surrounded and encouraged by older and intellectually accomplished uncles, aunts, cousins, and family friends, sharing their pride in the rich, centuries-old traditions of Bengali and Indian history and culture, polyglot from infancy, and always fizzing with curiosity about every subject under the sun, Sen never seems to have had any doubt that he would spend his life as a scholar, like his father and grandfather before him.

Advertisement

The only real question was, in which field? At various points in his teens, he was seriously tempted to pursue Sanskrit, mathematics, or physics, before settling on economics, not just because it combined analytical and mathematical reasoning with the real-life political and social problems that interested him, but also because (unlike the physicists, who had to do lab work) it left him free to spend his afternoons pleasurably absorbed in discussion with his friends in the coffeehouses and bookshops of Calcutta.

Intertwining his reminiscences with historical ruminations about his successive physical and intellectual homes, Sen’s memoir covers the first three decades of his life. It includes his childhood in Bengal and Burma; ten blissfully happy years of schooling at Santiniketan; the struggle for Indian independence and then the excitement of living in the young republic; Sen’s undergraduate life at Presidency College, Calcutta, followed by the start of a long association with Trinity College, Cambridge; and the initial stages of a glittering academic career—a professorial chair back in Calcutta at the age of twenty-two, a fellowship at Trinity, a year visiting MIT and Stanford, and finally a professorship at the Delhi School of Economics (and the birth of his first child) in 1963. Despite intermittent references to more recent events, Home in the World essentially omits his life over the following sixty years: Sen’s return to England in the 1970s, as a professor at the LSE and then Oxford; his life at Harvard and in the United States since the late 1980s; his election as the first non-English master of Trinity in 1998; his Nobel Prize that same year; his later marriages, family life, and many other achievements.

Sen never explains this reticence, but the book provides its own answer. For its major theme is that the intellectual questions to which he has devoted his life, and the insights about them that have made him famous, were inspired by his cosmopolitan upbringing and early experiences. From an early age, for example, he was surrounded by strong and brilliant female role models, yet he also noticed that in Burma and other places women were much more prominent in economic and public life than they were in India, and that the clever girls at Santiniketan were expected to downplay their achievements. As a boy he helped run night schools to educate the poor children in the villages around Santiniketan. Many of his older relatives were jailed without trial for trying to end British rule; he came of age among a generation of left-wing Indian intellectuals keen to help their new nation progress and prosper. From Tagore and from his family he inherited a passion for social justice and a firm belief in the essential pluralism of India’s, and the world’s, civilizations. Such influences shaped his abiding interests in questions of gender, justice, poverty, development, and social choice.

So did a series of deeply traumatic personal experiences. In the spring of 1943, when Sen was nine years old, starving villagers suddenly began to stream into Santiniketan. By the end of the summer perhaps 100,000 people had passed through the campus. The great Bengal famine, which eventually killed between two and three million people, had begun. For months, he and his classmates listened to men, women, and children crying for help as they desperately tried to make their way to Calcutta, where they believed they would be fed. When he visited the city, he saw people dying in the streets. Yet no one among his family or friends, anywhere in Bengal, ever had to worry about food. How could this be?

Decades later, Sen’s pathbreaking work on poverty proved that this horrendous but preventable catastrophe had been brought about not by harvest failure or food shortages, but by the booming wartime economy, British censorship of information, and colonial distribution policies, which had pushed prices so high that landless rural laborers could no longer afford rice. As he famously wrote, “Starvation is the characteristic of some people not having enough food to eat. It is not the characteristic of there being not enough food to eat.”4

A few months later, in 1944, at his parents’ house in Dhaka, the young Amartya was playing alone in the garden when he suddenly found himself confronted by a badly wounded man, covered in blood and screaming in pain, who had struggled through the gate. He was a Muslim day laborer called Kader Mia who had ventured into the Sens’ largely Hindu neighborhood looking for work so he could feed his starving family and had been attacked and stabbed by a mob of Hindu thugs. Sen and his father tried to save him, but he died. This encounter, and the horrific sectarian violence that led up to and accompanied the bloody partition of India in 1947, deeply affected Sen, as it did everyone who lived through it, and helped shape his abiding interests in economic (un)freedom, religious bigotry, and the politics of identity.

The final set of early influences was more purely intellectual. Sen’s memoir eloquently describes his exhilaration at encountering new ideas, the excitement of discussing and building on them, the joy of making friends with talented young people from around the world, and the pleasures of collaborating with other scholars. As an undergraduate he delved deeply into Marx, Mill, and Adam Smith. He was inspired by the work of Kenneth Arrow, Maurice Dobb, Isaiah Berlin, John Rawls, and other leading economists and philosophers. And he also ranged voraciously beyond his own disciplines, devouring Kipling, Gorky, Gilgamesh, Edmund Burke, Mary Wollstonecraft, J.B.S. Haldane, and Marc Bloch, as well as countless Bengali and Indian writers.

In 1952, having been dismissed by several unconcerned doctors, he diagnosed his own cancer of the mouth by studying medical textbooks on carcinomas. The life-threatening condition turned out to be treatable only through very high doses of radiation: for seven days in a row he had to sit alone in a hospital room for hours on end, holding in his mouth a lead mold containing radium. He passed the time by reading his way through much of George Bernard Shaw’s fiction and drama, several Shakespeare plays, a few of Eric Hobsbawm’s essays, and some material about a new left-wing history journal, Past and Present, which had just been launched in Oxford.

What is it like to be a brown person in the white world? Sen explains that as an Indian citizen he is “very used to standing in long queues at passport checkpoints” every time he travels, answering questions about the purpose of his visit, and assuaging the suspicion that he might be planning to illegally “stay on in whatever country it is I am passing through.” On one occasion, returning to England during his time as master of Trinity College, the Nobel laureate was interrogated at Heathrow by a border officer who was suspicious of the answers he had provided on the immigration form. Why had he put down “Master’s Lodge, Trinity College, Cambridge” as his home address? Was the master a close friend of his, to be offering him such hospitality? When Sen delicately paused before answering, it only heightened the officer’s misgivings.

Most people experiencing such an encounter would interpret it simply as confirming the well-documented racial prejudices of the British Home Office. But Sen chooses instead to treat it as the inspiration for a meditation on whether one can be one’s own friend. (Yes, he eventually responds to the officer, he is a friend of the master.)5 The same self-confident equanimity, intellectual curiosity, and generosity of spirit shine through this book. There are some wonderful vignettes of his life as an Indian in mid-twentieth-century Cambridge. When his friends come to bid farewell at the end of his decade there, one of them gazes pensively at Sen’s reproduction of one of Gauguin’s Polynesian group portraits. “Do you like the picture?” he asks her. “Yes,” she says, “they are your relations, aren’t they?”

His first landlady, Mrs. Hanger, had previously asked Trinity College not to send her any colored students. She had seen such people on trains and buses, she explains kindly to Sen when he arrives in the autumn of 1953, but never actually met one before. Her anxieties turn out to be practical. “Will your colour come off in the bath—I mean in a really hot bath?” she inquires. By the end of a year looking after Sen, she’s become a committed crusader for racial equality. When another woman at her dance club refuses to dance with an African who is trying to find a partner, she tells Sen, “I was very upset—so I grabbed the man and danced with him for more than an hour, until he said he wanted to go home.”

The only comparable memoir by a Nobel Prize–winning fellow of Trinity is the autobiography of Bertrand Russell. Its early chapters are a terrific read. Russell, too, had been brought up largely by his grandparents, though in rather different circumstances from Sen. His grandfather, the 1st Earl Russell, a former prime minister, died when Bertrand was six, and he was mainly raised by his grandmother, the austere Victorian Dowager Countess Russell, in her grand, rambling house, Pembroke Lodge, at Richmond Park. He was an orphan; aside from a brief spell at a local kindergarten, he didn’t go to school until he was almost sixteen, and was deeply lonely. On one occasion the elderly statesman William Gladstone came to stay, and the teenage Russell, as the only other male present, was left alone with him after dinner. The only thing Gladstone said was, “This is very good port they have given me, but why have they given it me in a claret glass?” “I did not know the answer,” Russell recalled, “and wished the earth would swallow me up. Since then I have never again felt the full agony of terror.”6

Yet by the end of Russell’s three large volumes, which doggedly cover every significant event of his long life, such human interest has largely drained away: we’re left with the verbatim printing of letters exchanged with heads of state and long recitals of places visited and important people met. Sen doesn’t altogether avoid such perils: as his chapters progress, we are introduced to more and more of his successful friends and colleagues and given potted histories of their later achievements. (He first meets Kamala Harris in 1964, when she’s a few days old; he is a friend of her parents at Berkeley and sits on her father’s Ph.D. committee.) But because his memoir is concentrated on the earliest part of his life, and perhaps also because so many of the luminaries he describes are no longer with us, it remains a wonderfully fresh account of people, conversations, and worlds that the rest of us can no longer inhabit.

It’s a particular thrill to catch so many glimpses of Sen’s outlook as a young man: hitchhiking through Europe soon after World War II; discussing Sanskrit drama with E.M. Forster in Cambridge; arguing about communism with his fellow students on the long boat voyage that first takes him from India to England; theorizing as a child about the relationship between the price of fish in Calcutta and the unpredictable results of local football matches; trying to get Santiniketan’s authorities to register his religion as Buddhist; clandestinely listening to the banned broadcasts of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Free India radio station during the war. As a schoolboy, he’s useless at carpentry, inadequate at sports, terrible at music, and is summarily dismissed from the officers’ training corps—after correcting the commanding officer’s imperfect grasp of Newtonian physics. But intellectually he’s irrepressible. Every time a new idea knocked at the door of his mind, he seems to have responded enthusiastically. Tagore would have been proud.

-

1

See Amartya Sen, “Tagore and His India,” The New York Review, June 26, 1997. ↩

-

2

Rabindranath Tagore, My Reminiscences (Macmillan, 1917), p. 72. ↩

-

3

A.B. Atkinson, “Original Sen,” The New York Review, October 22, 1987. ↩

-

4

Amartya Sen, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 1. ↩

-

5

Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (Norton, 2006), p. xi. ↩

-

6

The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell (Allen and Unwin, 1967–1969), volume 1, p. 56. ↩