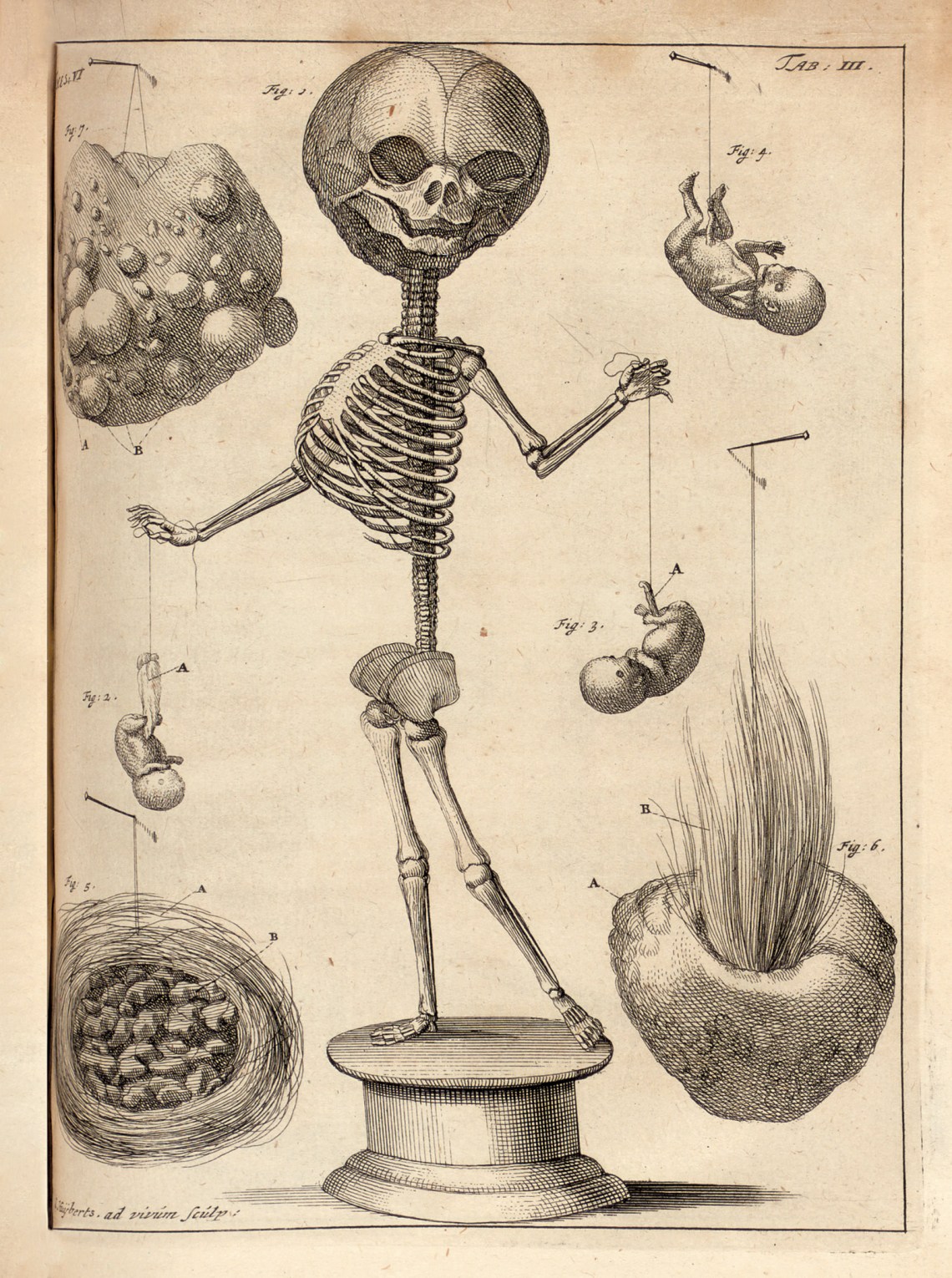

Almost every day between 1703 and 1730, Frederik Ruysch’s home at Bloemgracht 15, a narrow, four-story townhouse on a canal in Amsterdam’s Jordaan district, was open to visitors wishing to view “something unheard of, surpassing all belief, unless one should see it oneself.” On the ground floor, they first encountered a series of cabinets made of tropical hardwood and containing hundreds of exquisitely preserved animal and human body parts: a constantly changing selection of tumors, stones, and diseased organs, alongside “monsters”—conjoined-twin fetuses, deformed skeletons—and anatomical structures such as blood vessels, human ovarian ducts, and dissected whale eyeballs. Some of these were arranged into baroque tableaux and fantastical still-life compositions. One cabinet contained a walnut pedestal surmounted by a miniature cliff face composed of kidney stones, on which were arranged skeletons of second-trimester fetuses, their oversize skulls grinning as they flourished branching trees of arteries, stems of grass, and tissues delicately extracted from a woman’s bladder. The human remains in the tableaux addressed themselves to the viewer: one of the fetuses held a bone and the caption “Ah, fate! Ah, bitter fate!”; another skeleton, of a female child, wiped her eyes with a small pocket handkerchief; a third, lying beside the base of the kidney-stone cliff, cradled a preserved mayfly, gesturing to its own ephemeral existence.

Yet more remarkable were Ruysch’s “wet specimens” in jars, body parts that retained an uncanny appearance of life. The arms and heads of young children and stillborn babies floated in crystal-clear preservative liquid; some of the body parts were dressed with fringes of lace, tassels, or bonnets with exotic feathers held perfectly in place. The decorations were supplied by Ruysch’s daughter Rachel, a noted still-life painter. Other specimens were accompanied in their jars by embalmed scorpions or held out female reproductive organs for inspection. Visitors who expected the stench of decay or embalming chemicals were astonished that they didn’t smell. While the original tableaux have been lost and are known only through engravings, many of these jars survive. Three centuries after their assembly, the lifelike staring eyes of the specimens, the blush of their cheeks, and their suffused red lips still take the breath away, even as the disembodied heads expose their dissected craniums to the viewer.

To Ruysch’s guests, these display cabinets were marvels of both art and science. In an era when the divide between the two was less clearly drawn than it is now, they were hailed as “Rembrandts of anatomical preparation.” The composition of the tableaux evoked the groupings of Renaissance painting, the danse macabre frescoes of skeletons that chased one another around the walls of Catholic churches, or biblical scenes such as John the Baptist’s adoration of the Christ Child among the rocks. At the same time, they amazed visitors by revealing the internal structures of the body, not desiccated but in their “living” state and in detail so fine that it was often visible only with the aid of a magnifying lens mounted in front of them. There were suspicions that Ruysch was drawing on the secrets of magic and alchemy, particularly in preparing his liquor balsamicus, the embalming fluid in which the wet specimens were suspended with preternatural clarity. Its composition was a closely guarded secret, but it was reputedly a distilled spirit of unsurpassed purity, infused with exotic spices and perhaps the anatomist’s own blood.

Even today, many of Ruysch’s painstaking processes and techniques remain mysterious, as does the formula for his proprietary fluid. The wax sculptor Eleanor Crook, who contributed an essay to Frederik Ruysch and His “Thesaurus Anatomicus”: A Morbid Guide about her attempts to replicate his work, concludes that “the secret is an astonished understanding of how flesh is structured.” Although lymphatic nodes and vessels were known to classical medicine, Ruysch exposed their circulatory mechanisms in finer detail than anyone before him; he knew that flesh was not an undifferentiated spongy mass but a medium of liquid conductivity and exchange—as Crook writes, a “living forest floor of vanishingly small vessels, capillaries, interconnecting tunnels and loops, a constant chemical seethe.” She connects this understanding to a Dutch familiarity with fluid dynamics derived from constructing and maintaining canals, sluices, and locks.

Ruysch’s precise anatomical observation enabled him to develop techniques for injecting liquid wax, colored red by cinnabar, a compound of mercury, into the tiniest branches of the lymphatic system. Perfect control of temperature and humidity was required to prevent the preparation from clotting as it was delivered into delicate filaments with needles whose bores were hardly thicker than a hair. “When I see a rosy-cheeked Ruysch infant pleasantly dozing in his silk bonnet in a jar,” Crook writes, “I know from my experience with materials that what I am really seeing is a miracle of controlled perfusion and injection.” Ruysch himself compared the most delicate stages of the process to working with cobwebs.

Advertisement

In his own view, Ruysch’s work was both konst (art) and kennis (knowledge): the wonders of nature revealed as never before by a craftsman of genius. The aim of the collection, he wrote in its catalog, the Thesaurus Anatomicus, was to introduce the public to the wonders of anatomy and the possibilities for future research. He was aware of anatomy’s reputation as a malodorous and gruesome branch of knowledge, and his aesthetic embellishments were intended to “charm the eye” and “allay the distaste of people who are naturally inclined to be dismayed by the sight of corpses.” The inclusion of monstrosities was not prurient or sensationalist but a testament to the pluripotent creativity of divinely inspired nature. He was eager to provoke religious and philosophical contemplation in the viewer, and the poems and text captions in the tableaux were designed to frame the profound questions that his specimens raised.

Ruysch began his career as an apothecary’s apprentice in The Hague, where he was born in 1638. Having acquired a solid grounding in pharmacology, he moved on to study medicine at the University of Leiden, with its famous anatomical theater where students crowded into the steep-raked seats for a view of dissections and autopsies. Human cadavers were a limited resource, so after his studies at Leiden he took a post as city anatomist in Amsterdam to deepen his knowledge. In 1666 he was invited to join the guild of Amsterdam surgeons, and he became chief instructor to the city’s midwives. This gave him privileged access to stillbirths, miscarriages, and infant deformities, and the “harvest,” as he described it, from the autopsies he performed “grew to such bulk that a whole room could barely contain it.” His anatomical collection came to fill two rooms, and then three. In 1679 he was appointed doctor to the court of justice, allowing him to dissect executed criminals and to become an expert in forensic examination. Jan van Neck’s portrait The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Frederik Ruysch (1683) shows him manipulating a set of calipers to hold open the stomach of an infant cadaver on his operating table as an apprentice cradles a child’s skeleton mounted on a wooden pedestal beside him.

“Because it would have been wearisome to do nothing but handle Cadavers,” as he wrote in 1721, Ruysch took up the study of botany, becoming a professor at the Amsterdam Athenaeum Illustre in 1685. All this time he was assembling his collection of curiosities and finding ever more errors in the classic textbooks of anatomy. He discovered techniques for restoring suppleness to specimens stiffened by rigor mortis, rehydrating dried tissues, and tying off capillaries so he could inject air into them, allowing him to display them in a semblance of their living state. Embalming specimens was a problem that “tortured my wits for many years,” until he found “a certain technique” that allowed him to preserve in perfect condition “entire bodies, complete with all their internal organs, for centuries, & perhaps forever.”

The Thesaurus reveals Ruysch as a tireless self-promoter, and he succeeded in establishing his home as a popular attraction on Amsterdam’s Golden Age tourist circuit. An early coup was a visit in 1697 from Peter the Great, while the young tsar was in the city to inspect Dutch shipbuilding and port facilities. At six feet eight inches and with pronounced facial tics, Peter was himself an anatomical prodigy, and he developed a lifelong obsession with Ruysch’s specimens. On his initial viewing he was transfixed by the preserved body of a seven-year-old child, with a garland of flowers and a lace collar, who appeared to him to be asleep rather than dead: Peter was so moved he hugged and kissed the corpse.

Peter the Great’s obsession with the collection became part of Ruysch’s enduring legend. A century after his death, some of his tableaux reappeared in the celebrated anatomical collection of Jean-Joseph Sue the Younger at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris; Alexandre Dumas wrote about visiting it, and Honoré de Balzac’s 1831 novel La Peau de chagrin (The Magic Skin) included a scene in a curio shop where the protagonist encounters “a sleeping child modeled in wax, a relic of Ruysch’s collection, an enchanting child which brought back the happiness of his own childhood.” The collection’s literary life extends to the present day: Olga Tokarczuk’s Booker International Prize–winning novel Flights (2018) includes scenes of Ruysch lecturing at the anatomical theater in Leiden and speculations about the mysterious formula for his liquor balsamicus.

The centerpiece of this new volume is the first English translation, by Richard Faulk, of Ruysch’s Thesaurus Anatomicus, originally published in Dutch and Latin in ten volumes between 1701 and 1716. This has been a long-standing aspiration of the editor, Joanna Ebenstein, who has made this medical-historical niche her own: she cofounded the Morbid Anatomy Museum, which opened in Brooklyn in 2014 and closed two years later; she now runs the organization Morbid Anatomy, a global hub for lectures, courses, and events on the history, art, and culture of death. The new translation is buttressed with essays from Ebenstein’s expert collaborators—anatomical practitioners, curators, historians of art and science—and a generous, if challenging, selection of images, featuring engravings of the famous tableaux and photographs of the original cabinets and surviving wet specimens in their jars. All these combine to resurrect Ruysch’s collection and to recover a sense of his idiosyncratic curatorial style: a combination of anatomically precise annotations and wistful memento mori epitaphs, seasoned with P.T. Barnum levels of boosterism and denunciations of his rival anatomists.

Advertisement

At the same time, the book allows us to rethink an enterprise that seems even stranger to us today than it did to his contemporaries. Ruysch’s world captures a transitional moment between what have become, from our modern perspective, starkly contrasting historical eras: the seventeenth-century cult of the baroque and esoteric, and the rational and experimental endeavors of the scientific revolution that superseded it. Ruysch was an almost exact contemporary of Isaac Newton, who inhabited both these worlds but kept his occult investigations strictly demarcated from his science. Ruysch, by contrast, blended them into a distinctive vision that, over the course of his long career, shifted in emphasis from the former to the latter.

The model for his collection was the cabinet of curiosity, a private assemblage of treasured objects often known by the German terms Wunderkammer or Kunstkammer. “Cabinet” typically referred to a room rather than a closet or a piece of furniture, usually one in a grand or genteel private residence, that displayed sculptures and paintings alongside classical antiquities, medieval relics, and curiosities of nature: stuffed exotic animals, samples of amber or eye-catching mineral ores, artifacts from Africa or India such as ostrich eggs, bezoars, and coconut shells. By Ruysch’s time there were shops in Paris, London, and Amsterdam dedicated to supplying private collectors; a short distance from Ruysch’s house, Rembrandt’s studio housed a substantial collection that included a lion’s skin, classical busts, portraits from Mughal India, and a seashell for which the great painter paid a record price. (It may have been the Conus marmoreus that he depicted in an etching.)

Anatomical curiosities were a staple of such cabinets, and some famous collections specialized in them. In the late 1500s Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria, displayed at Castle Ambras, near Innsbruck, a series of rich oil portraits of human deformities: a man who had survived having his skull pierced by a lance, another with withered limbs who was painted wearing a ruff and a red satin cap, and a hairy-faced man from Tenerife dressed in courtly velvet robes.

Cabinets of curiosity are often considered the forerunners of museums, and some of Ferdinand II’s collection is now housed in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, much as the British Museum was inaugurated as a repository for Hans Sloane’s private collection of “natural and artificial rarities.” Yet their philosophy and organizing principles were rather different. Curiosity was a signature virtue of the early modern era, a counterpoint to the faith in tradition that underpinned the Middle Ages. It was an attribute of certain rare and novel objects, but also a sensibility: an urgent desire to know, with a particular affinity for the strange and exceptional. The curious observer was a delver into the secrets of nature, which might be revealed equally by studying occult signatures, observing monstrous and abnormal specimens, or deploying technologies such as the microscope to view intricate structures and life-forms that lay beyond the imperfect senses of the human observer.

The curiosity of this era tended to generate not the ordered and experimentally verified knowledge of the scientific era to come but a matrix of correspondences, oppositions, and paradoxes. Nature was a chain of being, an infinite series of emanations from the One in which each specimen was to be understood in relation to others. Anatomical organs and structures might be linked to other objects by astrological correspondences, shapes that revealed hidden significance, or affinities with a particular healing plant. Ruysch’s collection, particularly in its early years, was a web of such correspondences. Each cabinet was conceived as a unique work of art, and he constantly tweaked and rearranged the juxtapositions and paradoxes—between the natural and the artificial, the dead and the living, the beautiful and the monstrous, the whimsical and the solemn, the hidden forms of nature and the revealing scalpel. The memento mori homilies he affixed to his skeletons invited the visitor to contemplate these paradoxes, and above all to question the relationship between life and death. In the words of the poem that introduces one of his baroque tableaux of fetus skeletons, blood vessels, and kidney stones: “What is mankind? Or rather, what remains/When dirges cease and we are laid to rest?”

After 1700, however, as the philosopher of science Stephen Asma observes in his essay in Ebenstein’s volume, Ruysch’s project gradually oriented itself toward the emerging tenets of the scientific revolution. The motto he adopted, “Only believe your own eyes,” echoed the Royal Society’s Nullius in verba (Take nobody’s word for it), the rejection of authority and tradition in favor of firsthand and testable evidence. His arrangements became more orderly; he focused more on the mechanics of anatomy than on its correspondences with other aspects of Creation. He began to remove the “monsters” from his collection, preferring typical specimens: nature in its normal shape contained more than enough complexity and wonder. He gave his name to physiological features he discovered, such as the “Ruyschian coat,” a vascular membrane lining the back of the eye. His growing impatience with theory, together with the imperatives of material knowledge and medical advancement, was part of a tendency that, Asma suggests, “slowly ushered in the disenchanted world of modernism.”

By the end of his long life, Ruysch was operating in a different milieu from that which had formed him: one in which knowledge was linear and progressive, and competing theories were tested ruthlessly by experiment. The later volumes of his Thesaurus excoriate at length the material errors of other anatomists who “have attempted to foist on us countless Chimeras that do not merely stretch the truth, but that have in nowise been seen in the human body.” If anyone doubted Ruysch’s claims for the human anatomy, he wrote, they “have the opportunity to view them” any day of the week at his house. At the age of seventy-six he pronounced that the “master stroke” of his career had been to demonstrate that the cortex of the brain was composed not of glands, as other so-called experts had it, but of a pulpy arterial mass: “What mortal would believe that, unless he had seen it at my home with his own eyes?”

Ruysch’s work astonished his contemporaries with its truth to nature, while his artistry and moral delicacy mitigated its shock value and defended it against accusations of sensationalism. It is impossible to approach it in the same spirit today: the scientific precision is still breathtaking, but the sensibility to which it is harnessed is far outside the acceptable limits of modern taste, except perhaps at its gothic and transgressive margins. The disembodied faces of infants swathed in lace and tableaux of fetus skeletons violate the dignity, as well as the legal principles of informed consent, that we accord to human remains today. They are rendered still more disturbing by the baroque contrivance of their settings, a style we associate today with its debased and kitsch vestiges such as the seashell-and-coral mantelpiece decorations sold in beachfront souvenir shops.

The most obvious modern descendants of Ruysch’s project are the plastinated bodies of Gunther von Hagens’s “Body Worlds” exhibitions, a franchise of which is now installed in Amsterdam a short walk from Ruysch’s old house. These also inhabit the uncanny valley between life and death, and encourage viewers to meditate on the intricate structures of anatomy through technology and artistic display; but plastinated cadavers, anonymized and archly posed on bicycles or playing cards, are bodies without souls that make no attempt to communicate with us. Ruysch, by contrast, continually asks us to consider the subjectivity of his specimens, to reflect on their past life and their future state. He may have been moving toward a mechanical model of the body, but the boundary between the living and the dead was not so confidently defined.

In the centuries after Ruysch’s death, he was remembered as much for his metaphysical riddles as his technical achievements. The Italian poet and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi memorialized Ruysch’s collection in his 1827 “Dialogue Between Frederik Ruysch and His Mummies” (included in this volume), in which the specimens in the anatomist’s workshop come to life and converse with him. In this imagined scene, Ruysch is awakened at midnight by the sound of his cadavers talking and enters the cabinet to ask them, “Children, what kind of game are you playing? Have you forgotten that you’re dead?” He proceeds to interrogate them about whether they still feel sensation in the afterlife and what they recall of the moment of death. One of his skeletons replies that “the sensation I experienced differed little from the feeling of satisfaction that steals over a man, as the languor of sleep pervades him.” Just as we cannot remember the moment at which we fall asleep, death is an imponderable and insensible transition between the ephemeral and the eternal.

Ruysch’s collection exists today in a similarly ambiguous state. In 1716 Peter the Great visited it again, and in 1717 he bought it outright, together with the secret formula for the liquor balsamicus, for the unprecedented sum of 30,000 guilders, perhaps $3 million today. Ruysch began collecting anew, and the tsar shipped the tableaux and jars to St. Petersburg for display in the Kunstkamera, his new museum, in which he displayed “monstrous” human and animal births that he had requisitioned from across Russia, together with living children with deformities who were obliged to sweep the floors and tend the fires. It is unclear whether the tableaux, which were highly fragile and perishable, were ever displayed there: they may have been judged too shocking for public view, or they may not even have arrived in the first place. In 1747 the Kunstkamera was badly damaged by a fire in which much of the collection may have perished. No plausible documentation of the secret formula has ever been uncovered. The tableaux survive today only in the engravings reproduced in the Thesaurus, but the extant wet specimens in St. Petersburg, including the lace-draped arms and faces of deceased newborns, stare out at the world through fluid still sparklingly clear, with blushing faces and eyes that seem to have just awoken from sleep.