When Jorge Luis Borges was asked if he’d forgiven the Peronists of Argentina, he replied, “Forgetting is the only form of forgiveness; it’s the only vengeance and the only punishment too.” For Borges, forgiveness and vengeance were siblings because both make use of oblivion—as does the creation of art. “You should go in for a blending of the two elements, memory and oblivion,” he wrote of artistic creation, “and we call that imagination.” Kierkegaard agreed: “One who has perfected himself in the twin arts of remembering and forgetting is in a position to play at battledore and shuttlecock with the whole of existence.”

In Forgetting, the neurologist Scott Small likens the loss of memory to a chisel that hammers away at the marble of our lives, sculpting order and beauty from the block of raw experience. Lewis Hyde’s A Primer for Forgetting, which brings together reflections on memory, forgetting, and the commemoration of societal trauma, reminds us that the Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, was the mother of all the muses, and the songs she inspired had a twinned purpose: commemorating past glories while allowing listeners to forget themselves.

One of Borges’s most famous fictions, “Funes, the Memorious,” describes the case of Ireneo Funes, a young Uruguayan gaucho who, following a head injury, becomes cursed with an inability to forget. After his injury the vaguest of Funes’s recollections shine with brilliance and clarity; alone in his mother’s back bedroom, he imbibes English, Portuguese, Latin, and French by merely flicking through dictionaries. A ceaseless and faultless archive of mental images is instantly available; every configuration of clouds he has ever witnessed can be compared to the patterned endpapers of every book he has ever opened. But this prodigious memory proves useless, an obstruction to thought. “To think is to forget a difference, to generalize, to abstract,” wrote Borges. Funes himself admits to the narrator, “My memory, sir, is like a rubbish heap.” At the end of the story Funes dies of fluid overload, or “pulmonary congestion.”

Hypermnesia like that of Funes is very rare, yet it does exist—there’s a small but fascinating scientific literature exploring the peculiarities of such people.* As a family physician, I’m far more familiar with the reverse: people who have lost their memory through dementia. My work is to attend to their physical and mental health as best I can, as well as to support their carers and spouses. In my office I regularly encounter people worried about a deterioration in their memory; for them I conduct a quick physical examination, go through a questionnaire (the misleadingly titled “Mini-Mental State Examination”), do a series of blood tests looking for easily identified and reversible causes of confusion, and arrange a CAT scan of the brain. I never make a formal diagnosis of dementia after a single encounter—it’s as much about observation over time as it is about objective memory loss, and questionnaires and cognitive tests often give inconsistent results, even on successive days.

These conversations are even more familiar to Small, who specializes in dementia and leads a lab at Columbia University engaged in Alzheimer’s research. Forgetting is an accessible summary of his lab’s findings, and a plea for the scientific community to build on the insight of Borges—that to live, it is necessary to forget. Small describes himself as part of the tradition of “anatomical biology”—the belief that every element of our mental experience can be localized to specific brain structures—though he concedes that his is an extreme view. The approach has generated a wealth of understanding about what he calls the “hubs and spokes” of memory in the human brain, but it has proved less useful in understanding neurodiversity or mental illness.

Neurons have outputs, called axons, and inputs, called dendrites; new memories appear to be stored within the connections of tiny protuberances or “spines” in the dendrites of a part of the brain called the hippocampus. These spines shrink as we sleep—the sleeping brain apparently selects which memories to lay down for long-term storage and which to let go. As the Nobel laureate Francis Crick put it, “We dream in order to forget.” Without this sleep-fueled forgetting, our brains become overloaded and our senses distorted.

A diminution in the function of the heart leads to heart failure; of the lungs, to respiratory failure. Dementia could be characterized as a type of brain failure. It is therefore not a diagnosis per se, but a constellation of symptoms with diverse causes. There are several causes of dementia, such as poor blood flow to the brain (vascular dementia), protein deposition (Alzheimer’s), loss of dopamine (Parkinson’s), and so on. One of the reasons I always check a CAT scan of the brain in someone with memory loss is because I hope to find a reversible cause such as a tumor or hematoma.

Advertisement

In its early stages, dementia is often indistinguishable from normal aging, in which the older brain may naturally begin to show signs of cognitive impairment. Neither dementia nor cognitive aging is currently reversible, though they may be slowed through diet, exercise, and keeping the mind agile with social and intellectual activity. Drugs to slow dementia are not particularly effective, and even the new monoclonal antibody treatments show only a modest benefit. Small is anxious that specialists like him be honest about the prospects for treatment. “As life spans expand globally, cognitive aging is emerging as a worldwide epidemic,” he writes. “Effective lifestyle interventions, if they can be found, are better than drugs in ensuring equal access to all.”

Forgetting has a focus on Alzheimer’s disease: a pathological brain process in which there is accumulation of “amyloid plaques” between brain cells and “neurofibrillary tangles” within them—through a microscope the former look like blooms of lichen and the latter like dark scribbles. Its cause hasn’t been identified, and treatments are in their infancy, though it’s known to be a condition distinct from cognitive aging, not an acceleration of a natural process. Until recently the diagnosis couldn’t be made definitively without a biopsy or postmortem, but Small writes of new techniques that can detect evidence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebrospinal fluid, opening up the possibility of diagnosis by way of a spinal tap.

Memory is never like a steel trap, Small writes: “It is flexible, form-shifting, and fragmented”—even for those with excellent recall. He shows how forgetting is just as active a process as remembering, with its own molecular signature, and goes so far as to describe it as a cognitive gift. It works in concert with memory to make meaning out of the chaos of sense impressions we bombard our brains with every day. Forgetting also helps us with behavioral flexibility—finding novel solutions to unexpected situations. Even machine-learning networks perform better when they are allowed to forget:

By testing different computer algorithms, computer scientists have learned that adding more memory—the equivalent of adding more dendritic spines—will not improve pattern recognition of faces or of anything else. Instead, the more effective way to artificially create human computational flexibility is to force the algorithm to have more forgetting. In computer science, this type of forgetting is sometimes called dropout, meaning a particular level is forced to reduce the number of artificial synapses dedicated to processing a facial feature—the digital equivalent of our own normal cortical forgetting.

Networks programmed solely to remember are good at fine detail but end up too rigid for the dynamism of the real world. By ramping up their ability to forget, facial-recognition networks grasp the “gist” of a face rather than every detail, allowing them to identify the essence of someone’s features irrespective of expression or lighting.

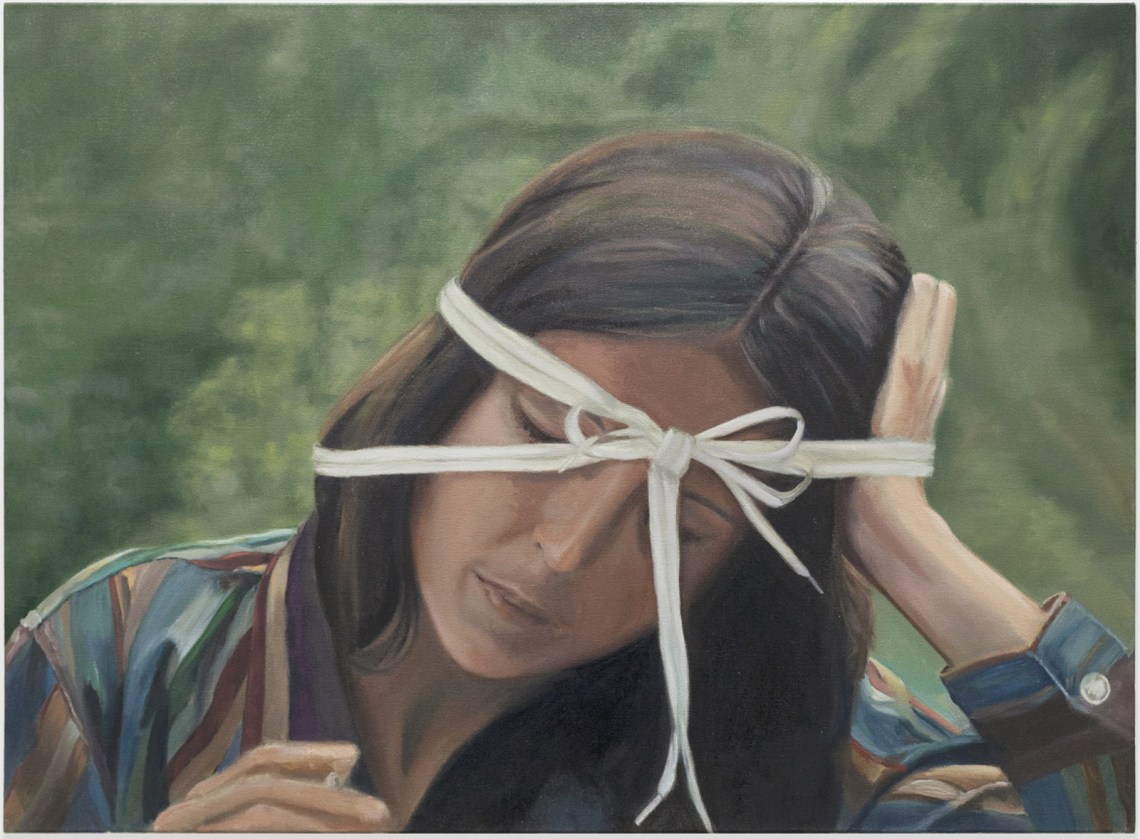

Forgetting takes in elements of Small’s research and clinical experience as a neurologist but swings into discussions of other aspects of memory loss, through conversations with a series of male mentors. We meet the psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman to explore how forgetting can help a physician’s diagnostic ability; the neuroscientist Eric Kandel, with whom Small did his Ph.D.; the late, great Oliver Sacks; and Jasper Johns, with whom Small sets out to gauge the value of Willem de Kooning’s late work, which was painted while the artist was suffering from Alzheimer’s.

One of the most fascinating of these excursions is with Yuval Neria, a professor in Columbia’s Department of Psychiatry and a decorated veteran of the Yom Kippur War. Neria is an expert on memory and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the two men quickly fell to discussing Small’s military experience as an Israeli soldier sent into southern Lebanon on June 6, 1982. His unit was tasked with taking Beaufort Castle, a medieval fortress surrounded by trenches, then held by Syrians. “Trench warfare, with its close-range gunfire and hurtling explosives, is typically one of the goriest types of battle,” Small writes, “and that night at Beaufort Castle was no different—so gruesome, in fact, that I refuse, as I have done ever since, to go into its bloody details.” Neria wanted to know how many of the soldiers from that operation subsequently developed PTSD. Small began to ask around and turned up an unexpected finding: none.

PTSD is in many ways a disorder of excessive memory, in which experiences we’d rather forget return to haunt us in flashbacks freighted with emotion. Neria and Small began to explore why his unit had been spared PTSD. Following the conquest of the castle, the men had been pulled back to a small British Mandate–era barracks in northern Israel. There they began to drink whiskey and vodka, smoke pot, and put on a series of theatrical skits for their own entertainment. Unhappy with Reagan’s enablement of the war and Washington’s “over-coziness” with Israel, the performers made lewd gestures while wrapped in an Israeli flag and put on a mock binational funeral ceremony for Israel and the US:

Advertisement

As I listened to my own voice recounting the details, it struck me how the skit now seemed more silly than satirical. But for Yuval what mattered was that we had engaged humor, whether sophisticated or sophomoric. He explained how the skits probably functioned like exposure therapy: as we played out emotional elements of our memories over and over again, we bathed them with humor, bleaching out their bloody hue.

One of the greatest risk factors for the development of PTSD is finding oneself isolated after a trauma, unable to process the experience and without a protective social fabric. Small writes that he and his fellow soldiers were held in an environment of “brotherly love” and were able to act out their conflicted feelings about the killings they’d been pushed into perpetrating. Small theorizes that even the alcohol and pot they consumed may have helped—anesthetizing their brains at a time when they might otherwise have been setting down painful memories. Even so, he is convinced it was the camaraderie and fraternity of his unit that saved him:

As a non-golden Israeli who can’t shake some of his abrasive tendencies, as a neurologist who has been indoctrinated to treat pharmacologically, and as a neuroscientist who tries to reduce many things—even sometimes absurdly—to molecules, I now appreciate a simpler and more elegant way to enhance our innate capabilities to emotionally forget: socialize, engage life with humor, and always, always try to live a life glittered with the palliative glow of love.

Later in the book Small moves on from personal traumas to national ones and, following his experience in Lebanon, explores how societal trauma might be honored and remembered without collateral emotional damage. He was at his hospital in Washington Heights with medical colleagues as news of the terrorist attacks came through on September 11, 2001. There was a mounting sense of fury and demand for vengeance. “One potential benefit of growing up in the war-ridden Middle East is that it can sensitize you to the pitfalls of nationalism,” he writes. “Most of the people in that room were unfamiliar with the carnage caused by foreign terrorists, in this case in both their homeland and their hometown, and so this reaction was understandable.” As news of the atrocity filtered in, “rageful xenophobia…against all ‘Arabs,’ against a whole people” became widespread, even among colleagues he thought of as liberal and tolerant, though by a few days later, “cooler minds prevailed.” Small’s explanation of that cooling process is fascinating: he credits communal activities such as candlelight vigils on Manhattan street corners and gatherings at “makeshift downtown galleries of the dead and missing,” with New Yorkers “viewing the hundreds of multicultural faces and silently mouthing their names.”

Just as networks function better if they’re allowed the latitude to forget, creativity is enabled when associations between concepts remain “loose and playful.” Lewis Hyde has written books on poetry and gift economies, on trickster figures in history and culture. A Primer for Forgetting takes the form of four notebooks (titled “Myth,” “Self,” “Nation,” and “Creation”) and is explicit in its adherence to a freestyle playfulness, replete with avuncular erudition—Hyde’s customary syncopated, counterintuitive, scattershot but gloriously variegated style. “What a relief to make a book whose free associations are happily foregrounded,” he writes in its introduction, “a book that does not so much argue its point of departure as more simply sketch the territory I have been exploring, a book that I hope will both invite and provoke a reader’s own free reflections.” Just as Small explores how too vivid a memory can sow the seeds of PTSD, Hyde explores how communities that overcommemorate past traumas experience the syndrome’s crippling societal equivalent.

The word “amnesty”—which comes from the same root as “amnesia”—is a legalized form of forgetting invented around 400 bce in Athens to help a society recover after civil war. My hometown in Scotland enacted a similar law in 1560 after years of sectarian civil conflict: the Treaty of Edinburgh stated, “All things done here against the laws shall be discharged, and a law of oblivion shall be established.” The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) insisted that, to secure peace after the Thirty Years’ War, memory of particular atrocities “shall be bury’d in eternal Oblivion.” Hyde explores the “amnesic amnesty” that followed the death of Franco in Spain, and the informal pacto del olvido that allowed a traumatized society to postpone addressing the brutalities of that regime—even dismissing them (for a while) as a product of collective madness:

Spanish law allows immunity from prosecution in cases of mental illness, so this third way of framing the conflict was popular during the transition with its “pact of forgetting” and its amnesic amnesty. “The whole of Spain lost its head,” the newspapers said. “We must take into account the collective insanity.”

Hyde posits a distinction nested within the word “forget” that I’d never encountered: between true “forgetting” and Spain’s state-sanctioned insistence that victims on both sides “forget about” seeking reparations—at least temporarily. He suggests that it takes decades for a society to achieve enough distance from a trauma to appraise it properly, to be able to bring to it the kind of humility and forgiveness required for reconciliation. Tony Judt’s Postwar (2005) argued that the brisk adoption of such willed collective amnesia facilitated Europe’s astonishing recovery after World War II, and Hyde recounts how, in the former Yugoslavia, Slobodan Milošević set out specifically to counter the kind of amnesia that had been promoted under communism, fanning with his speeches the flames of grievance that still flickered six centuries after Serbia’s defeat by Ottoman Turkey. He quotes the Irish activist Edna Longley on the damaging Northern Irish obsession with the commemoration of ancient hurts: “We should erect a statue to Amnesia and forget where we put it.” Hitler’s bunker in Berlin is now buried under an anonymous parking lot—much better, Hyde thinks, than honoring it with a monument and plaque.

Vamik Volkan is a psychiatrist who has worked with “contending ethnic, religious, or national groups—Arabs and Israelis, Serbs and Bosniaks, Turks and Greeks, Estonians and Russians.” His book Bloodlines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism (1997) proposes that peoples may single out a “chosen trauma,” which Hyde unpacks as an “identity-informing ancestral calamity whose memory mixes actual history with passionate feeling and fantasized grievance and hope.” Communities that choose such traumas lock themselves into ceaseless conflicts, as each generation is called upon by its elders to “never forget.” In this way Hyde implies that Israel is in danger of burdening itself with the societal equivalent of the kind of PTSD that Small escaped.

As an antidote to such willed remembering, he quotes the Holocaust survivor Ruth Kluger: “I think of redemption as closely linked to the flow of time. We speak of the virtues of memory, but forgetfulness has its own virtue.” For Kluger, Holocaust memorials risk becoming part of a “cult” that imposes on children a rigid, conflict-generating vision of history. “A remembered massacre may serve as a deterrent, but it may also serve as a model for the next massacre,” she wrote. “We cannot impose the contents of our minds on our grandchildren.” Reading her words, I was reminded of a Palestinian poet I once heard read in Haifa who called upon his elders and his own generation not to “forget” but to “forget about” the Nakba, in the sense that they should move on and focus instead on defeating the apartheid that governed the lives of everyone living between the Mediterranean and the Jordan—a land de facto ruled by one power.

For Hyde, the foundational trauma of the United States is the near extermination of Native Americans, followed closely by the reverberating legacies of slavery. Long sections of the book are devoted to examinations of the Sand Creek Massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by John Chivington and his cavalry in the Colorado Territory in 1864, and to the murder in Mississippi of Charles Moore and Henry Dee by Klansmen in 1964. His focus is on how these atrocities can be commemorated without burdening families and descendants with a toxic legacy of fury, and he lists some of Volkan’s questions even as he gives examples of successful reconciliation:

• How can the symbols of chosen traumas be made dormant so that they no longer inflame?

• How can group members “adaptively mourn” so that their losses no longer give rise to anger, humiliation, and a desire for revenge?

• How can a preoccupation with minor differences between neighbors become playful?

• And how can major differences be accepted without being contaminated with racism?

It takes courage to stand up against those who insist on the commemoration of ancient hurts. In search of examples of those who have succeeded, Hyde quotes the Diné (Navajo) activist Pat McCabe/Woman Stands Shining, who has written of her own plea to her murdered ancestors in a Facebook post:

I said to them, that we would love them always, and forever, but that somehow we must forget, or let go of, all of the violence that had come before now, or we ourselves would complete the job of genocide that the US government began. I begged them, my ancestors, to let us go free. I told them they must find their way all the way home to the Spirit World.

And then I prayed with all my heart, and all my tears, and asked for Creator to open the gate for them to travel, and to leave us in peace, and for them to find peace beyond the gate, and for each of us to travel in the correct way once again, each in our own world, me in this Earth Walk world and they, true ancestors in the Spirit World.

Mark Twain wrote that the American Civil War could “in great measure” be blamed on the novels of Sir Walter Scott, bloated as they are “with the silliness and emptinesses, sham grandeurs, sham gauds, and sham chivalries of a brainless and worthless long-vanished society.” If the drama and theater of novels can lead societies to war, Hyde wonders whether more authentic drama and theater could be harnessed for a new kind of memorial—one that might lessen grievance and encourage peace.

Following his poignant account of Thomas Moore’s decades-long search for justice after the murder of his brother Charles, Hyde imagines a pavilion on the eastern bank of the Mississippi “dedicated to the memory of African Americans murdered during the centuries of American apartheid.” Its walls would be etched with the names and testimonials of all those for whom the circumstances of death are recorded. Anyone visiting the pavilion would be assigned the name and story of one victim and be taught the circumstances of that person’s life and death:

From the center of the pavilion, a spiral staircase will descend to a level below the river. The names of the many thousands dead will be inscribed on the walls of the descending shaft, and visitors will drag their hands across these names as they go such that the inscriptions will be fully erased in three or four centuries.

Oblivion is coming for all of us eventually, and three or four centuries seems to Hyde like an appropriate length of time to hold on to the names and stories of the victims of these atrocities. For many, that will be too short, but both of these books excel at reminding us that forgetfulness is not only desirable but necessary. People who have suffered from transient amnesia often look back, Hyde says, on their forgetfulness as a kind of golden period and feel homesick for the freedom and levity with which they lived for a while, unburdened by the responsibilities of remembering.

Interwoven through Hyde’s curious, impressionistic, rich, and provocative ruminations on forgetting is a memoir of his mother’s evolving dementia. She became, in the end, unable even to remember his name. I recognized from my own patients his description of her joy in still being able to fold laundry for the community of her retirement home, something satisfying and worthwhile that contributed to the community in which she lived. Many of my own patients have a dread of dementia, fearing that forgetfulness will rob them of their humanity. But as Small reminds his readers, the suffering occasioned by Alzheimer’s is sometimes worse for family members than it is for the person with dementia. Like Small, I try to find ways to remind my patients that a diminution in memory does not entail a diminution in humanity:

We seem unaware that many cognitive abilities are not critical for our being—our core personality traits, our ability to socialize with family and friends, our ability to laugh and love, to be moved by beauty.

The Greek myth of Hades imagined the souls of the dead drinking from the waters of Lethe in order to forget; the river’s name is related to the word letho—“I am hidden.” Forgetfulness is the permission to let specifics become hidden, to become buried under the inevitable accumulation of new memories and events created by the ceaseless dynamism, flourishing, and churn of the world. Every act has consequences that change that world in some way, no matter how modest, and those actions will go on changing the world for millennia after we are gone. But to remember the details of every action is to invite madness, to paralyze our brains and our communities with memory.

Borges’s Funes was just nineteen when he lost the capacity to forget, and he lived only two more years. His world became “almost intolerable it was so rich and bright”; reality and the accumulation of memory was like a hot, indefatigable pressure that bore down on him. Borges seems to have anticipated the discoveries of neuroscience in that sleep, with its pruning of memory, was for a mnemonist like Funes almost impossible. The only way he could rest was to turn in the direction of new houses, the insides of which he had never seen, and picture them “black, compact, made of a single obscurity.” Then he’d picture himself lying on the bed of a river, “rocked and annihilated by the current,” and wait for peace.

This Issue

March 9, 2023

Peddling Darkness

Having the Last Word

Private Eyes

-

*

See, for example, E.S. Parker et al., “A Case of Unusual Autobiographical Remembering,” Neurocase, Vol. 12, No. 1 (February 2006). ↩