On July 16, 1975, Jamaica’s conservative newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, published an ominous headline paraphrasing Prime Minister Michael Manley, the leader of the leftist People’s National Party: “No One Can Become a Millionaire Here—PM.” In an ill-tempered story, the paper fizzed with fury at the heresy of the prime minister’s anti-individualistic and anticapitalist vision for the country, reporting that his advice to “anyone who wants to become a millionaire in Jamaica” was to “remember that planes depart five times daily to Miami.” Manley, The Daily Gleaner concluded some months later, was “the most messianic figure in Jamaica’s political history”; he had courted Fidel Castro and brazenly aligned Jamaica with Communist Cuba.

A few days after the “breaking news” about millionaires, Manley felt the need to clarify that his criticism had been specifically directed at those whining upper- and middle-class compatriots who were “motivated only by the selfish desire to become a millionaire overnight” and who “refused to regard themselves as part of the Jamaican society and owing an obligation of service like the rest of us.” His qualifications came too late; many middle-class families had already packed their bags. Those leaving the Caribbean island joined thousands who had previously made the roughly six-hundred-mile journey, just two hours by plane. Indeed, so many Jamaicans decamped to South Florida and to Miami in particular that the city quickly earned the sobriquet “Kingston 21,” making it an honorary district of Jamaica’s capital.

In If I Survive You, Jonathan Escoffery’s stunning debut work of fiction, the parents of Delano and Trelawny are among those well-heeled refugees who have turned their backs on Jamaica. As a young man the boys’ father, Topper, luxuriated in the kind of comfort befitting the only son of uptown Kingston parents. Such an individual, Topper informs us, has options: “You can take Daddy’s Datsun or Mummy’s new ’68 VW and fly past street urchins who sell bag juice and ackee at red lights down Hope Road.” Even though those options may have been limited by Manley’s focus on the island’s poor “sufferahs” and his determination to establish a more equitable society, Topper and his wife, Sanya, were still privileged enough to embark on one of those five daily flights.

But they didn’t flee the country out of antipathy to the hard-line Communist state they believed to be on its way; they rushed to get out because they feared for their safety. By the mid-1970s Jamaica had become an extraordinarily violent society. Even the exponent of “One Love,” Bob Marley, was forced into exile in 1976 after would-be assassins broke into his compound with guns blazing. The wounded reggae star was fortunate to escape with a bullet lodged in his arm, but many others perished as the island descended into anarchy and virtual civil war, with politically motivated gunmen responsible for hundreds of murders.

Though in Escoffery’s fiction the word on the street is that “mostly it man who live in zinc house and homeless who live in the gullies that dead,” the threat is increasingly worrisome to middle-class Jamaicans. From Mandeville, a sleepy town in the center of the country, Topper calls his parents back in Kingston and learns:

Gunman lick down them door and tie up you mummy and daddy, and thief off them money and jewelry and everything. Daddy them pistol-whip and you mummy…God knows how them feel her up so, even when she old to rass. But him tell you say it could have gone worse.

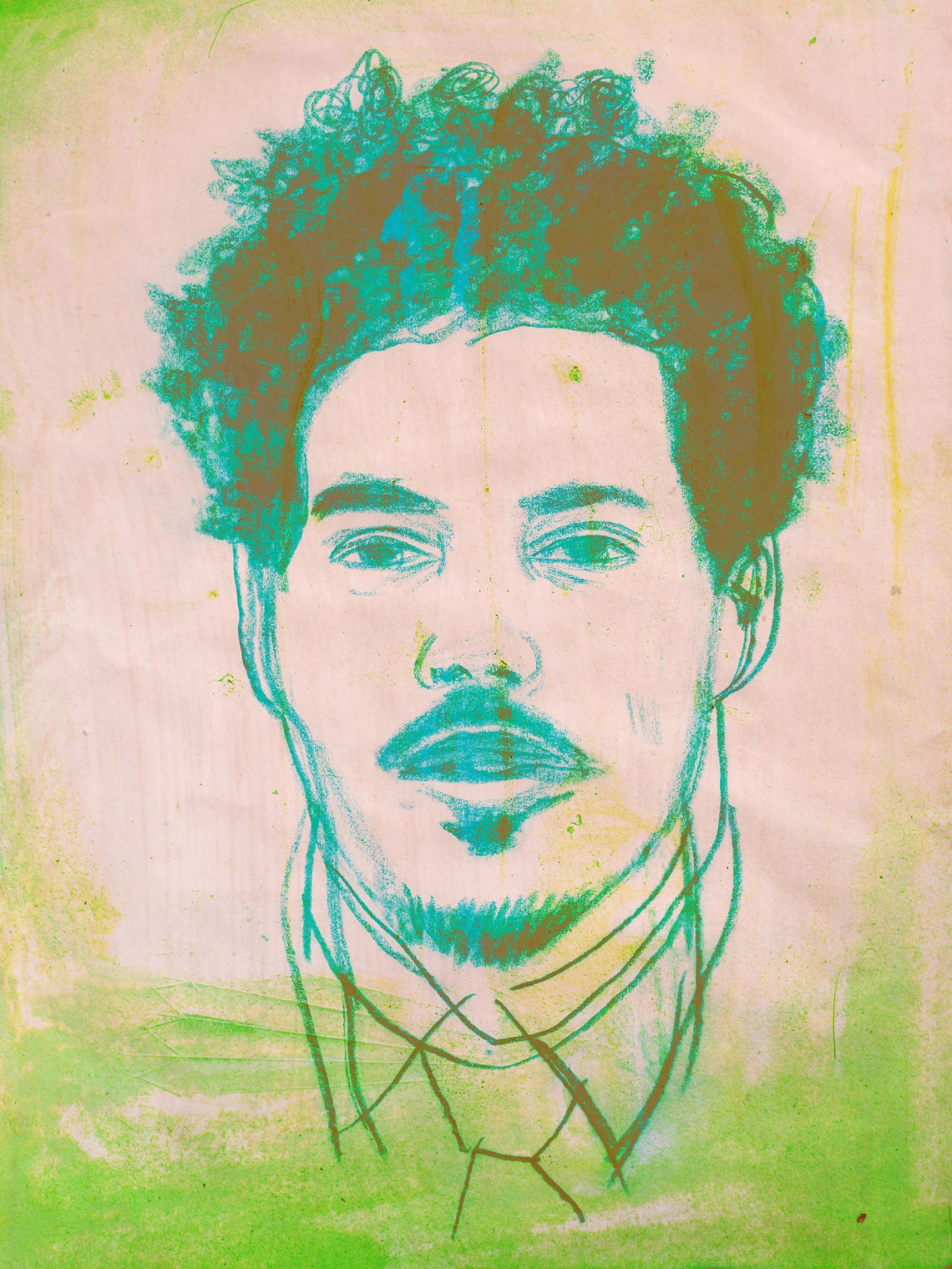

Topper is not so sanguine; he’s galvanized to seek a coveted visa to the US. The escalating violence marks a grim turn of events, but there’s an ease, exuberance, and energy about Escoffery’s writing, and despite its darkness it is thrilling to read. If I Survive You is a collection of eight interconnected short stories, one of which, “Under the Ackee Tree,” won The Paris Review’s 2020 Plimpton Fiction Prize. Escoffery’s prose, by turns muscular and delicate, is vivid and expressively true to the Jamaican voice, especially to the bilingual ability of the middle classes (Topper is an exception) who, when off the island in Miami, savor their accents and code switch, when it suits them, from standard English to patois.

The chapters can be read as stand-alone stories. The book, though, feels like a novel, partly because the central characters, Topper and his sons, appear throughout; Sanya is vividly depicted but has only a supporting part. Each story is told from a particular character’s perspective, so the reader gains a sense of their progression over more than twenty years. The overarching narrative, then, is not chronological; it’s episodic, zipping back and forth in time and occasionally repeating information that has appeared elsewhere.

As suggested by the title, this is a tale of survival. These children of immigrants are their parents’ experiment in surviving in a foreign land and culture. Like many immigrant parents, Topper is almost exclusively concerned with financial security; he doesn’t attend to his sons’ emotional health. In his shamelessly Darwinian approach to survival, there’s no room for softness or empathy for others, though he is given to bouts of sentimentality.

Advertisement

The overriding theme of If I Survive You—migrants struggling to improve their circumstances and wrestling with new identities, minimum-wage poverty, and the threat of natural disasters—is echoed in a number of recent collections of short stories, perhaps most notably Bryan Washington’s Lot (2019), set in different districts of Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. But in its tone and ability to freshly conjure an underexplored world, If I Survive You has more in common with Drown (1996), Junot Díaz’s collection of stories that range from the barrios of the Dominican Republic to the bruising streets of New Jersey.

Escoffery grew up in a Jamaican household in Miami, and in his book he evokes the tug of nostalgia felt by migrants. The younger son, Trelawny, is born in the US and named after a parish in Jamaica to remind his father of home. Like many people around the world, Jamaicans regularly undertake internal migrations, moving from the countryside to the capital and bringing their country ways with them. But the transfer to the US is of another magnitude and presents unexpected challenges. At one point, recounting his experiences, Topper laments how the Caribbean newcomers find that the host culture is not so accommodating:

You miss walk down a road [in Jamaica] and pick Julie mango off street-side. When you try pick Miami street-side mango, lady come out she house with rifle and shoot your belly and backside with BB. In the back of your Cutler Ridge town house, you start try grow mango tree and ackee tree with any seeds you come by, but no amount of water or fertilizer will get them to sprout.

How to ensure against rejection or at least to mitigate its effects is a theme that pervades the book. One solution might be to recreate home when abroad. Ackee, Jamaica’s national fruit and an essential ingredient of the dish ackee and saltfish, serves as a powerful metaphor for identity and belonging. One morning Topper sits his sons down to breakfast to

try teach them them culture to make sure it survive. The tropical market on Colonial start carry canned ackee…so you cook the boys ackee and saltfish…. You see this here, you say. The ackee grow in a pod and it must open on it own or else the ackee poison you. You point to the picture on the can…and it remind you that you never eat ackee out of no can before.

Later in the story the older son, Delano, seizes on ackee as a way to secure a victory over Trelawny in their rivalry for their father’s affection. Trelawny may be more academically gifted, but Delano’s emotional intelligence is keener. He cements his status as favorite when, as a young adult, he arranges, much to his father’s delight (his “eye start water”), for an ackee tree to be transplanted to the family’s backyard.

Trelawny, whose story is central to the book, is bemused by the idea of recreating Jamaica. Escoffery reflects this in the choice of language used by his characters: Topper speaks in a heavy patois; Delano, his Jamaican-born first son, is bilingual, flicking between American English and Jamaican patois. But Topper notes disappointedly that when Trelawny “start talk, you can’ believe it: is a Yankee voice come out.” Trelawny is keen to blend in and dial down the difference between him and his classmates, children of the host nation. In the aptly titled opening story, “In Flux,” this difference is brutally laid bare when, on a career day at Trelawny’s school, Topper (who has struggled to eke out a living as a used car salesman and is now a general contractor) attempts to explain his job to the class. “When man need dem bat’ room fix, is me get all di plaster an’ PVC an’ t’ing,” he says in broad, barely comprehensible patois.

There’s further discomfort and confusion for the family over America’s racial hierarchy, which does not fit the familiar Jamaican model. Notwithstanding the fact that the vast majority of Jamaica’s population is black, few among the aspiring middle class would accept that description of themselves. Sanya, the boys’ snobbish mother (when she sucks her teeth in displeasure, she produces a sound “akin to industrial-strength Velcro ripping apart”), claims to have Jewish and Irish ancestors.

Advertisement

The belief that your social status degrades with too close an association with Africa results in the kind of genealogical pretension that Zora Neale Hurston skewered in “How It Feels to Be Colored Me”: “I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother’s side was not an Indian chief.” When, in his final semester as an undergraduate, Trelawny questions his mother about their identity (“Are we Black?”), Sanya answers with undisguised pride that “our last name comes from Italy,” and what’s more that their pedigree is even further enhanced: “‘Your grandmother’s father,’ and she lowers her voice to a whisper when she says this, ‘may have been an Arab.’”

Trelawny shifts through various identities, trying each one on before discarding it, as none seems to fit. His features and cinnamon complexion make it possible for him to have a chameleonlike existence before he is outed. At one school he hangs out with the Puerto Rican boys, until their suspicions are aroused by the fact that he can’t speak Spanish. When he confesses that his parents are from Jamaica, his Latino friend shoots back, “Wait. You’re Black?” Later, Trelawny is attacked by African American boys after being mistaken for Puerto Rican; and later still, a white colleague draws his attention to the distinction between African American and Caribbean:

At the warehouse where you work, a White coworker asks you to help him “nigger-rig a pallet.”

“Is that really the kind of thing you want to say to me?” you ask him.

“What do you care? You’re not Black. You’re Jamaican,” he says.

It’s all too dizzyingly unsettling for Trelawny, and the confusion over identity doesn’t let up: it follows him to college in the Midwest. There the locals do not have a nuanced understanding of race; he is simply considered black, but he is not alone in being racially reduced. He gravitates toward undergraduates who reassure themselves that though they might originate from Mexico, China, or Argentina, they should be considered white:

“Just because my mother is Jewish, all of a sudden I’m treated like I’m not White here.”

“Oh, you’re White.” The Mexican places a sympathetic hand on the brown-haired woman’s arm. “Don’t worry.”

“Aw, you’re White, too,” she says, returning the arm pat.

It’s at such moments that Escoffery’s sly humor and finely calibrated dialogue come to the fore. The cultural complexities of race are further demonstrated back in Jamaica when Trelawny’s father, on a visit to the island, drives to a mountainside ghetto and is asked by a man guarding its entrance, “White man, you ’ave business ’ere?” Topper nearly laughs and questions why he, a man of color, would be described as white: “And him say, You the whitest man me ever see, and him no say it with humor.”

Topper and Sanya are relieved to have escaped the financial uncertainty and violence of Jamaica. But it’s impossible to deny and difficult to resist the call of home, even if it turns out to be a siren song. On a trip to Jamaica for his parents’ funeral (they are said to have died in a road accident, but everyone knows the truth: gunmen murdered them), Topper finds solace in an act of fleeting sexual congress with a local woman. A year later, following an unexpected pregnancy and the birth of a child—though he questions whether he is really the father—he feels compelled to return once more to Jamaica and at least to assuage his guilt with a bundle of cash. He arrives at an inhospitable place with “shacks made of lean-to zinc,” a shantytown where “you can see don’ nobody here have phone.” With an economy of writing that as the book progresses seems increasingly to be a signature strength, Escoffery paints a poignant picture of pitiless poverty, crowned by the child’s presentation to his father, as he kneels in a rusted hovel on a blanket of dirt and immediately sees two things: “Him have your eyes, fi true, so him must be yours. And that the baby dead from time.”

The matrimonial deceit blankets Topper’s marriage in an emotional frost that threatens never to thaw. Indeed, Sanya’s antipathy toward her husband hardens with his unchecked, feckless behavior. Trelawny notes, “Mom blamed the white rum, the nights Dad disappeared, then reappeared reeking of debauchery. Dad claimed she’d become too Americanized in her expectations of marriage.”

The endpoint of separation and divorce is soon reached and with it comes the arrangement that the parents should each take one of the boys. Trelawny is then in the sixth grade; his brother is four years older. Unsurprisingly, their father chooses Delano. That decision sows a seed of resentment that will lead a decade later (after Trelawny has graduated from college) to an altercation between father and son and an act of violence that prompts Topper to kick Trelawny out of his house.

The story “Odd Jobs” follows on from this family cataclysm. By now Sanya numbers among the returnees who have gone back to Jamaica permanently. The unemployed Trelawny is out of luck and out of sorts; he has no choice but to live in his car, changing parking spaces at the local shopping center every few hours. He believes, though, that his fortunes will change when he happens across a Craigslist posting: “I’VE NEVER HAD A BLACK EYE…” In it an entitled college girl named Chastity explains that she both needs the bruise for a photo project and wants to experience what it feels like to be punched. The ad ends with “sorry, no black guys.” But Trelawny responds anyway because, he admits, “I’d reached the point in my starvation where personal ethics and phenotypic traits couldn’t deter me.”

Off-the-scale stupidity, surely. The warning bells should have rung at every stage, but it’s a mark of Escoffery’s creative power that Trelawny’s unlikely signing on for the gig feels convincing, as it reveals his desperation and lack of insight. This won’t end well. After some hesitation at Chastity’s upscale apartment, he agrees to her final plea: “You don’t even have to use closed fists. Just slap me a little.” On his second attempt, Chastity topples over. Still, she wants it harder, so he straddles her, tugs on her ponytail, and hits her “with certitude” until “tears streaked her taut cheeks.” Trelawny begins to worry that he’s gone too far but then surprises himself with what comes out of his mouth: “Do me now.” Before Chasity can comply, her parents walk through the door and their violent response to what they see is all too expected.

Escoffery’s exploration of the lure and commodification of danger among middle-class Americans stultified by their wealth is darkly funny and unsettling. Growing up as the child of Jamaican migrants to the UK, I recall how those “blessed” relatives who went to the US were often spoken of with awe. America’s meritocratic culture allowed them to fulfill their potential and succeed, we were told, whereas the UK’s environment stymied ambition. General Colin Powell, whose parents were Jamaican migrants to New York, was celebrated as the personification of that notion and embodiment of the American dream. On September 26, 1995, The Times of London carried a story that contrasted the general’s fortunes with those of his British cousins:

Mentally reclothe Colin Powell. Remove that immaculate and bemedalled military uniform…. Dress him instead in a London bus conductor’s drab grey garb and imagine the man…punching the bell above his head, and bawling “Fare please!”…Had the chips fallen slightly differently this, not America’s adulation, could well have been General Powell’s fate. After all, this is more or less how two of his first cousins ended up.

Escoffery’s book challenges that received truth. Despite all the advantages of life in North America, his fictional Jamaican family seems destined for skid row. Social mobility is possible, but the trajectory is downward. The sense of an imminent but avoidable emotional car crash and our voyeuristic interest in it particularly informs the story “If He Suspected He’d Get Someone Killed This Morning, Delano Would Never Leave His Couch.” The story centers on the elder brother, who earlier in the book starts a tree-surgery business and has a family living in the suburbs. Delano is undoubtedly a poster boy for the possibility of successful transition from immigrant to respected citizen. But he, too, is down on his luck; his business has been hit badly by the calamitous 2008 recession. With a natural disaster predicted, though, he spies an opportunity.

The story, weighted with dread from the start, opens with the news that Key West residents are expected to begin evacuating in advance of Hurricane Irene. If Delano can get his confiscated truck back from Rusty, the garage owner, and a contract from the manager of a housing complex to fell its trees before the storm knocks them onto cars and houses, then he’ll be back in business.

The odds are against him. The complex’s manager, Tina, has yet to forgive Delano for spurning her previous sexual advances. He must now seduce her to get the contract, but after his business pitch, Tina’s expression is “that of someone watching a grown man vomit on himself.” Worse still, hell would freeze over before Rusty would release the truck. Delano’s tree-surgery crew also presents formidable challenges, especially his deputy, Nordic, who when it comes to violence “doesn’t speak in metaphor.” His most vexing problem is the fading possibility of rapprochement with his wife, who reminds him, “You’re not a provider, Delano. You’re a liability.”

Delano’s life, so promising when he was entering adulthood, has been stunted by the fluctuating fortunes of his business. He is disheartened to recognize that he is at best a compromised, degraded soul who “deteriorated in the ways one can while still waking up on the right side of the dirt.” None of his difficulties seems surmountable, yet “still an idea slips through, despite his efforts to contain it. An idea that he controls his destiny.” Delano is obviously deluded. He steals back the truck. But it turns out to be dangerously faulty, resulting in an accident with Mikey, one of his spliffed-out workers: “He calls Mikey’s name, but the truck’s arm is already catapulting the bucket to its apex, windmilling Mikey and his screaming chain saw into a hemorrhaging street.”

No, it doesn’t end well. And finally, in the last story (which gives the book its title), we’re back to moral corrosion with Trelawny scrolling through Craigslist ads. There’s a feeling of déjà vu, as he yet again defaults to an unwise choice in helping a couple of “attractive young professionals,” Tim and Morgan, both white, spice up their sex life:

WATCH MY BOYFRIEND AND I…

We are looking for someone to watch us in bed. Preferably 6’2″ or taller…. PREFERABLY BLACK.

Trelawny at least registers the jeopardy this time: “You consider that Morgan prefers Black guys because when one goes missing no one bothers to look for him.” A black, second-generation immigrant may have more social stock than an economically challenged African American, but Trelawny is not likely to fare any better in his precarious position. And no, this also doesn’t end well.

Readers might shake their heads and remind themselves that Delano and Trelawny are the sons of immigrants who, had they stayed in Jamaica, were destined for comfortable, privileged lives. This unraveling of fortunes is not supposed to happen to people like them. But is it kismet, or are their parents to blame?

Invariably among migrants there’s a tension between nostalgic romantics who dream of returning to their homeland and hard-nosed pragmatists determined to stay. A central question posed by If I Survive You concerns the emotional cost of displacement: Do financial betterment and the prospect of living the American dream outweigh the long-term erosion of a sense of one’s former self? Finally, can the decision by Topper and his sons to remain in the US be considered a success?

Judgment comes at the end of “Under the Ackee Tree.” In celebration of his retirement, Topper summons those members of his family who are still on reasonable terms with him to a poolside party at his Miami house. The family’s tenacity and ability, albeit compromised, to thrive on foreign soil is symbolized by the fact that Topper’s ackee tree has started to bear fruit. On the night of the party, there’s a hum of contentment reflected in the seductive lights draped from the roof of the pool deck and the old-time reggae music playing in the background as celebrants slam dominoes down on the table. But the festive mood darkens as “man start in on the white rum” and Topper’s tongue loosens. In the increasingly vexed discussion about the state of Jamaica (“Boy, is Manley mash up the country”), and the wisdom of leaving the island (“Soft boy like you [Trelawny] would’ve dead longtime”), Topper offers a stinging assessment of his “defective” younger son. Trelawny walks out of the argument burning with humiliation; he is soon seen in silhouette under the ackee tree with an ax in his hand, repeating to himself:

I’ll chop down your tree.

I’ll chop down your tree.

I’ll chop down your fucking tree.

Trelawny wields the ax, but the violence is emblematic of the years of frustration that not only he but also his brother and father have felt; in subsequent stories, the half-destroyed ackee tree appears as a recurring motif of the migrant family’s failure to thrive in the US.

The bleakness of “Under the Ackee Tree” runs right through to “If I Survive You.” Now, a few years after the ax incident, the adult brothers are living together, sharing once more the house where they grew up. But both are struggling: a dreadlocked Delano dreams of making it big as a reggae musician, although he doesn’t actually have a band; Trelawny is a poorly paid high school teacher who aspires, and threatens, to buy out his brother from the house, even though it is sinking.

They are rivals in desperation: Who will sink and who will swim? Delano strikes first when Trelawny is at work: calculating that he needs his brother’s room as a rehearsal space for his future band, he clears out Trelawny’s possessions, dumps them on the front lawn, and changes the lock on the front door. The pathos is rendered, as in much of the book, with humor; the backwash of pity at the naiveté of each brother’s scheme for self-improvement is tempered by the brio of Escoffery’s writing. In this story, as in all the others, there are echoes of how émigrés’ social capital disappears in their adopted homelands, and how they and their descendants are reduced to lives of permanent jeopardy, of uprooted temporariness.

As Trelawny’s options narrow for evading homelessness and penury so, too, his luck runs out and his judgment falters. The paid nonparticipating observer of white middle-class sexual coupling contemplates participation when lured back by Morgan to the luxury apartment when her partner is out of town. As he knocks back cocktail after cocktail, the tequila courses through Trelawny’s body, and he drifts through time, feeling simultaneously that he’s on Morgan’s couch and “diffused across the universe, on an infinite trajectory.”

In this mental state, freed from his troubles, he has a premonition of a better future. He imagines escaping both the prison that his life has become in Miami and the path to self-destruction he has forged for himself. But it doesn’t last long. Trelawny soon succumbs to the notion that escape is a fantasy: “It occurs to you that people like you—people who burn themselves up in pursuit of survival—rarely survive anyone or anything.”