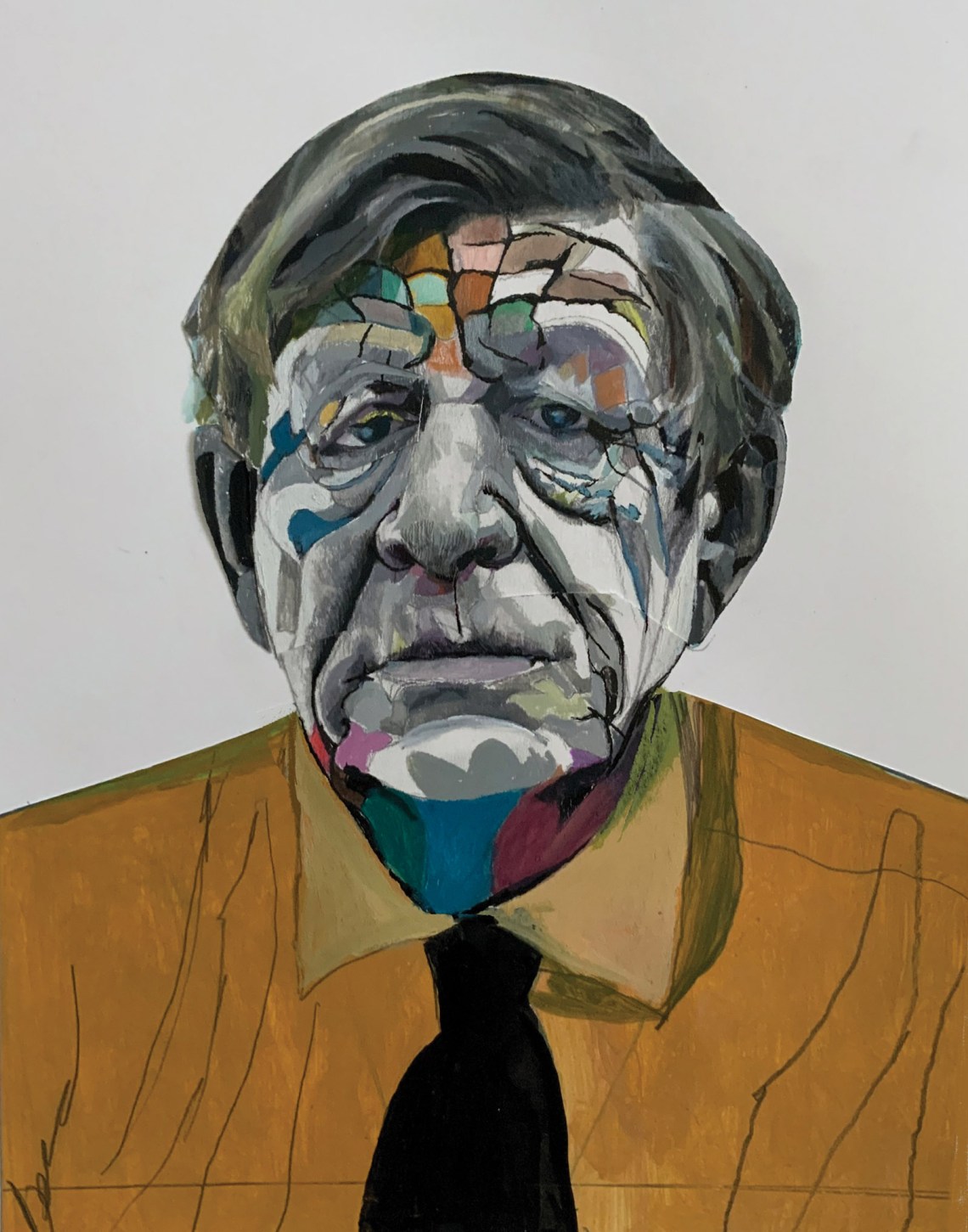

The two volumes of Poems by W.H. Auden (edited by Edward Mendelson, his tireless literary executor) contain all the poems that he published, submitted for publication, or sent to friends for “posthumous” publication from 1927 until his death in 1973, along with Mendelson’s scrupulous textual notes. The books run, in total, to almost two thousand pages and come seven years after the sixth and final volume of Prose, which gathered the essays, reviews, and autobiography.1 Mendelson edited all of them—publishing the first volume of Auden’s prose (1926–1938) back in 1997—and wrote the definitive and fulsome critical biographies Early Auden (1981) and Later Auden (1999).

Mendelson has been studying, explicating, and collating Auden’s work for more than fifty years, since Auden asked him, around 1970, when Mendelson was a young teacher at Yale, to help organize his uncollected essays into what became Forewords and Afterwords (1973). Mendelson, recalling the selection process to another biographer of Auden’s, Richard Davenport-Hines, said the poet

asked me why I didn’t include his essay on Romeo and Juliet, and I simply shook my head no, as a slightly nervous way of saying I didn’t think it equaled the rest. At this, he beamed at me, and I realized he was delighted that I didn’t think everything he wrote was worthy to be engraved in gold.

Still, whatever Mendelson thought then, he has now given us everything, or almost everything. (A final volume, Personal Writings: Selected Letters, Journals, and Poems Written for Friends, is forthcoming.) It’s been an astonishing act of literary scholarship and personal dedication on Mendelson’s part, and readers the world over should be thankful for it.

In the twentieth century those interested in poetry had to come to terms with the big beasts of the initials: W.B., T.S., and the upstart, W.H.—and it’s no exaggeration to say that the publication of Auden’s Poems in October 1930 by Faber and Faber, his first commercially published collection, changed poetry in English. Here, from a twenty-three-year-old, was a new tone in the language, a different way of saying, pushing back against expectations of rhythm and syntax and referent. The poems were strange, rich, authoritative.

Certain tropes percolate through the early poetry—stratagems, machinations, espionage—and have been read as symptoms of adolescent rebellion, or the resistance of youthful leftism against the bourgeois establishment, but it’s hard now not to see much of it simply as a consequence of the necessary sexual coding, its power derived from what could not be said. “Here am I, here are you:/But what does it mean? What are we going to do?” (It’s worth remembering that homosexuality was subject to criminal sanctions in Britain until 1967, when Auden was sixty.2)

Take the fifteenth poem (they are numbered rather than titled) of the thirty in his first collection:

Control of the passes was, he saw, the key

To this new district, but who would get it?

He, the trained spy, had walked into the trap

For a bogus guide, seduced with the old tricks.

At Greenhearth was a fine site for a dam

And easy power, had they pushed the rail

Some stations nearer. They ignored his wires.

The bridges were unbuilt and trouble coming.

The street music seemed gracious now to one

For weeks up in the desert. Woken by water

Running away in the dark, he often had

Reproached the night for a companion

Dreamed of already. They would shoot, of course,

Parting easily who were never joined.

“Who would get it?” indeed. The poem tells us itself that the “new district” has a “key,” a code, a way of being read. The texture is not without precedent in English literature—the heavy alliteration (line 10, for example, has “weeks,” “woken,” “water”) harks back to Anglo-Saxon verse—though the tone feels entirely new. There is a straightforward-enough reading: a “trained spy” has been betrayed by a “bogus guide” and is now in enemy territory. He’s been abandoned by his handlers and seems sure he will be shot. But ambiguities multiply suggestively. There is an oddness, a dream logic to the lines: water runs away in the dark, the desert seems to bring us to a landscape more psychological than actual. Its symbolism seems allegorical.

Auden thought that modern poetry, which he defined as “poetry of the last fifteen centuries,” “means and cannot help meaning more than and something different from what it expresses, so that the reader is required to play a creative role,” and “The Secret Agent,” as Auden later titled the poem, demands to be read as both literal and figurative: there’s a metaphor being extended here. Although Mussolini had closed the alpine passes into France and Italy in 1927, providing a ready political interpretation for the contemporaneous reader, the isolation the poem explores is romantic, and the “new district” seems the world of sexuality.

Advertisement

Written the same year, 1928, that the OED records the first use of “pass” in the sense of an amorous advance, the poem counsels the self on the importance of sexual continence or restraint or subterfuge. In his notes Mendelson explains that “Greenhearth is a variant of Greenhurth, a mine in Teesdale, near Alston,” and Auden’s decision to use the variant is not accidental. The hearth, the locus of the household, is a fine site for a dam, meaning also a female parent, and easy power, meaning also heterosexual normality—but “they” will not allow it. Trouble is coming.

The last line is taken, as many have pointed out, from the Old English poem “Wulf and Eadwacer,” the monologue of a captive woman to her outlawed lover. It reads, “þaet mon eaþe tosliteð þaett naefre gesomnad waes” (One can easily split what was never united). This allusion casts Auden’s whole poem as one of frustrated love—but what exactly is parted? Lovers or the poet’s own body and soul, which were never joined? Is the poem referring to the impossibility of fully inhabiting his own desires, of matching the inward and the outward—the public and private faces he wrote about so much?

Astonishingly fluent, Auden could write poems of immense power that take their subject matter head-on. When it came to love poems, more circumspection was needed, but using the second-person pronoun licensed a direct approach of sorts: “Lay your sleeping head, my love.” Though he later became famous for lines that have the feel of diagnostic epigrams (“We must love one another or die”) or generalizing maxims (“About suffering they were never wrong,/The Old Masters”), the early poems are necessarily oblique, and this vital hedging and coding gives rise to a new style. “Audenesque” came to mean minatory, knowing, allusive, densely enigmatic. Behind that approach lies also a very English irony, a refusal to stand entirely foursquare behind the thing being said, a tone that allows some play within it. And play, for Auden, created a space where he could exist in his complexities.

Auden’s dialectic—the puckish, unruly youth versus the adult diagnostician—was there from the start, and finds embodiment in “Paid on Both Sides,” which opens Poems. “Paid on Both Sides” is an odd saga of two feuding families, set in the North of England, and has much of the telegraphed, stylized action of, as he called it, a charade. It’s tonally all over the place, teetering now toward farce, now tragedy, but the following scene is worth quoting at length since it shows—in his first public outing as a writer—elements of Auden out in the open, in competition and dialogue with each other:

[Enter DOCTOR and his

BOY]

B. Tickle your arse with a feather, sir.

D. What’s that?

B. Particularly nasty weather, sir.

D. Yes, it is. Tell me, is my hair tidy? One must always be careful with a new client.

B. It’s full of lice, sir.

D. What’s that?

B. It’s full of lice, sir.

D. What’s that?

B. It’s looking nice, sir….

X. Are you the doctor?

D. I am.

X. What can you cure?

D. Tennis elbow, Graves’ Disease, Derbyshire neck and Housemaid’s knees.

X. Is that all you can cure?

D. No, I have discovered the origin of life. Fourteen months I hesitated before I concluded this diagnosis. I received the morning star for this. My head will be left at death for clever medical analysis. The laugh will be gone and the microbe in command.

X. Well, let’s see what you can do.

[DOCTOR takes circular saws, bicycle pumps, etc., from his bag. He farts as he does so.]

B. You need a pill, sir

D. What’s that.

B. You’ll need your skill, sir. O sir you’re hurting.

[BOY is kicked out.]

The schoolboy humor attempts to subvert and deflate the adult dignity and certainty and self-congratulation (“I have discovered the origin of life”); the unresolved tension between these two aspects of Auden’s character was to play out in his work for the rest of his life.

In his review of Isaiah Berlin’s The Hedgehog and the Fox, Auden quotes Berlin’s famous thesis: hedgehogs “relate everything to a single central vision,” while the foxes “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory.” Dante, Plato, Hegel, Proust, Nietzsche, and Ibsen are hedgehogs, while Herodotus, Aristotle, Molière, Montaigne, Goethe, and Joyce are foxes. Auden goes on:

I find this classification entertaining and illuminating, but I think it needs elaboration. Are there not artists, for example, who, precisely because they can perceive no unifying hedgehog principle governing the flux of experience, are aesthetically all the more hedgehog, imposing in their art the unity they cannot find in life?

Of course he is talking about himself. Making sense of his experience, for Auden, involved synthesizing in his art the disparate and divided, using formal principles, metric or syllabic or stanzaic. (“Talent,” as Yeats noted, “perceives differences, genius unity.”)

Advertisement

Being an inveterate schematizer,3 Auden cannot resist a further categorization when it comes to Berlin, who takes his two classes of thinkers from Archilochus. Auden, in response, goes to Lewis Carroll: all men, he insists, may be divided into Alices and Mabels. (Mabel is one of Alice’s friends, who “knows such a very little.”) Auden’s elaboration is slightly nonsensical—he decides that a Mabel is an “intellectual with weak nerves and a timid heart, who is so appalled at discovering that life is not sweetly and softly pretty that he takes a grotesquely tough, grotesquely ‘realist’ attitude,” and he puts Donne, Schopenhauer, Joyce, and Wagner in the Mabel column—but it’s typical of Auden to steer the argument to childhood.

He thought that “to grow up does not mean to outgrow either childhood or adolescence but to make use of them in an adult way. But for the child in us, we should be incapable of intellectual curiosity.” The “intricate play of the mind” allowed Auden to entertain, as it were, notions, and he was intellectually promiscuous, always open to new modes, new thoughts. Eliot’s well-known observation of Henry James, that he had a mind so fine no idea could violate it, might be reversed in Auden’s situation. He was interested in everything—in psychology, Christianity, opera, Thucydides, Diaghilev, Tolstoy, Shakespeare; or, to take some examples from his poem “Spain 1937,” “the enlarging of consciousness by diet and breathing,” “the diffusion/Of the counting-frame and the cromlech,” “the photographing of ravens,” “the divination of water,” “the origin of Mankind,” “the absolute value of Greek,” “the installation of dynamos and turbines,” “theological feuds in the taverns” …

In A Certain World, Auden’s commonplace book, he reproduces Schiller’s lines from On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1795): “Man only plays when, in the full meaning of the word, he is a man, and he is only completely a man when he plays.” Play is a way of existing in full, of not being caught or trapped in attitudes or poses, just as Auden could shrug off communism and try on Freud, or shrug off Englishness and become American.4 Play can be flippant, but it can have the seriousness and gravity of the nursery rhyme, of the psychoanalytical or metaphorical truth—the truth of the archetype, say—and it allows one to cleanly interact with the experience of symbols, of relations, of exploration of the other, of the forbidden, without falling foul of moral or common law. It is also, of course, a resistance to tyranny, to the strict imposition of order, whether that be the po-faced doctor or the stern housemaster or the fascist dictator.

Auden is the brilliant trickster, the naughty boy with a stink bomb and a devastating verse about the Latin master. The tone can be tiresome—“plague the earth/with brilliant sillies like Hegel/or clever nasties like Hobbes”—and his lighter verse can stray a bit too far toward showing off. Some of the epigrams or shorts seem to anticipate the awfulness of Instagram poetry—“Nothing can be loved too much,/but all things can be loved/in the wrong way”—and I could do without much of the marginalia and clerihews: “Martin Buber/Never says ‘Thou’ to a tuber:/Despite his creed,/He did not feel the need.”

But Auden introduced, or tried to, a certain kind of irony into American poetry, even as America was teaching him the revelations of a more puritan, more direct way of being, or of reporting being. (In The Sea and the Mirror, his long poem-as-commentary on The Tempest, he has Prospero ask, “Can I learn to suffer/Without saying something ironic or funny/On suffering?”) As he told a Time interviewer in 1947:

People don’t understand that it’s possible to believe in a thing and ridicule it at the same time…. It’s hard for them, too, to see that a person’s statement of belief is no proof of belief, any more than a love poem is proof that one is in love.

Wystan Hugh Auden was born in York in 1907, the youngest of three boys. (His brothers became a farmer and a geologist.) When he was a year old, his father, George Auden, became the school medical officer for Birmingham, and the family moved there. Dr. Auden served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in Gallipoli, Egypt, and France during World War I. Auden boarded at St. Edmund’s prep school in Surrey, where he met Christopher Isherwood, who became his lifelong friend, his collaborator, and in the late 1920s and 1930s, his lover. Between 1920 and 1925 Auden boarded at Gresham’s School in Holt, Norfolk, and at the suggestion of a fellow pupil, Robert Medley, with whom he was in love, began to write poetry.

Hardy, Edward Thomas, the Anglo-Saxon poems were important early influences. (Fittingly, perhaps, considering the extensive criticism and poetry he wrote looking to Shakespeare, his first poem was published in the school magazine under the typo “W.H. Arden.”) He went up to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1925, where he studied natural science, then PPE (politics, philosophy, economics), and finally English, under the medieval scholar Nevill Coghill, graduating with a third-class degree but a university-wide reputation for his brilliance and for his poetry. As an undergraduate he read and imitated Eliot, Gertrude Stein, Edith Sitwell, and Laura Riding.

After Oxford, Auden went to Berlin with Isherwood for nearly a year and embarked on many sexual affairs, mainly with male prostitutes. Eliot published Auden’s Poems in 1930, and while teaching at Larchfield Academy, Auden wrote The Orators: An English Study, which deals with the country’s social and political landscape after World War I and with his homosexuality. A state-of-the-nation census, an elaborate diagnosis of “this country of ours where nobody is well,” it’s wild in its techniques, combining, among other things, a prize-day speech at a school, a “Letter to a Wound,” an airman’s journal with accompanying diagrams, genetic and psychoanalytical theory, a sestina, an airman’s alphabet, Pindaric odes… In the foreword to its reprint in 1966, Auden wrote:

As a rule, when I re-read something I wrote when I was younger, I can think myself back into the frame of mind in which I wrote it. The Orators, though, defeats me. My name on the title-page seems a pseudonym for someone else, someone talented but near the border of sanity.

From 1932 to 1935 Auden taught at Downs School in the Malvern Hills, enjoying the teaching and gossipy company of his colleagues and their charges. (“The aim is training character and poise,/With special coaching for the backward boys.”) In 1934 he took a motoring holiday in Central Europe with two of his former pupils at Downs, one of whom was Michael Yates, with whom he was infatuated. In 1935 Auden temporarily left teaching to join the GPO Film Unit, writing the “verse commentary” for the documentary Night Mail (1936), and married Erika Mann, the lesbian daughter of Thomas Mann, who needed a passport to leave Germany. In 1936 he wrote a play, The Ascent of

F6, with Isherwood, and he published the collection Look, Stranger! (published in the US the following year as On This Island), which contains some of his loveliest lyrics (“Out on the lawn I lie in bed”) and shows signs of Auden accepting his sexuality. The military metaphors are reprised, for example, in poem XXVI, but it turns out the passes do not need to be controlled:

That night when joy began

Our narrowest veins to flush

We waited for the flash

Of morning’s levelled gun.

But morning let us pass

And day by day relief

Outgrew his nervous laugh…

By 1937 the thirty-year-old Auden was regarded as the leading poet of his generation (and the voice of the socialist youth) in England, a reputation that had spread across the Atlantic. That year New Verse dedicated a double issue of the magazine solely to celebrating his work, and contained tributes from elder statesmen like Pound and up-and-comers like Dylan Thomas. Thomas’s real feelings were revealed in a letter to James Laughlin, not long after Laughlin’s founding of New Directions, in May 1938:

Auden is, I think, 31. I am 23. I don’t know Auden, but I think he sounds bad: the heavy, jocular prefect, the boy bushranger, the school wag, the 6th form debater, the homosexual clique-joker. I think he sometimes writes with great power: “O Love, the interest itself in thoughtless heaven, Make simpler daily the beating of man’s heart.” I can’t agree he’s as bad as [Archibald] MacLeish. He’s overpraised of course. I’ve added my own little dollop of praise in a number of New Verse devoted entirely, with albino portrait and manuscript, to gush and pomp about him. He’s exactly what the English literary public think a modern English poet should be. He’s perfectly educated (& expensively) but still delightfully eccentric…. He’s just what he should be: let him rant his old communism, it’s only a young man’s natural rebelliousness, (& besides, it doesn’t convert anybody: the awarding of conservative prizes to anti-conservatives who are found to be socially harmless is a fine, soothing palliative, & a shrewd gesture. And, incidentally too, the rich minority can always calm down a crier of “Equality for All” by giving him individual equality with themselves).

Although Thomas himself was no stranger to inhabiting the caricature of Poet, readers coming from a working-class, state-educated background might share some of his reserve. While we’re at it, reading much of Auden’s work again, one notices the absence of women in his poems. They are either abstracted (“By landscape reminded once of his mother’s figure”) or cartoonish and misused, like Edith Gee (in the ballad “Miss Gee,” from Another Time), who has a “slight squint” and “no bust at all.” She dies of cancer and is hung from the ceiling to be dissected by Oxford students. Auden’s world is a male world, with male actors in it.

In the 1939 travelogue Journey to a War, written with Isherwood, an account of their visit to wartime China the previous year, Auden described America as “absolutely free” (one might quibble and ask for whom, exactly?), and in January 1939 Auden and Isherwood made the move there, arriving by ocean liner in New York Harbor. Initially the trip was to be for a year, and they were going to write a travel book called Address Not Known. Auden ended up staying in New York on and off for thirty-three years. Isherwood headed to Hollywood to write screenplays.

In his first year in New York, Auden, then thirty-two, met the eighteen-year-old Chester Kallman, who was, as The Cambridge Companion to W.H. Auden rather brutally puts it, “an aggressively ‘out’ and promiscuous homosexual who, though Jewish, had the stereotypical ‘Aryan’ good looks Auden favoured.” Through turmoil and betrayals and temporary separations, Kallman and Auden were to remain partners for the rest of Auden’s life.

His attraction to the country was partly about escape from the old certainties: he told Robert Fitzgerald that “America is the place because nationalities don’t mean anything here, there are only human beings, and that’s how the future must be.” Auden found new subjects and concerns in the United States—early on he befriended the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who was influential in his return to Christianity, which is, according to Auden, “a way, not a state, and a Christian is never something one is, only something one can pray to become.” Kallman’s Jewishness provided him, however, with access to a different set of references, and Kallman also got him interested in grand opera. They collaborated on libretti, including Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress (1951).

Auden’s move to America prompted some rancor in the literary world. He was recruited to the Morale Division of the US Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany,5 where he interviewed German citizens about the war and “got no answers that we didn’t expect.” He returned briefly to London in 1945, and Robert Graves’s attitude seems not untypical: “Ha ha about Auden: the rats return to the unsunk ship.”

So much has been written about Auden—and so much was written by Auden—that it can be difficult to keep the poems in view. There is the chaotic love life, the twenty years of daily amphetamine use, the squalid domesticity, the last, lonelier years, and all the gossip—he made Anne Sexton cry backstage at Poetry International; in Austria he lent his car to Hugerl, a male prostitute, who used it in a bank robbery, during which it got a bullet hole in the hood; when his flat on St. Mark’s Place was too filthy he used the toilet in the local liquor store; Hannah Arendt took him shopping and made him buy a second suit…

The received idea about Auden is that in the later work the complicated ambiguous truths elicited by play, by the parabolic, are overtaken by a more public, more life-involved tone, and the received idea is mostly true. It’s also thought that Auden’s American years produced less memorable and influential poems, although this is a more arguable proposal. The later books contain more than a few works of genius: Nones (1951) has “In Praise of Limestone,” and The Shield of Achilles (1955) contains “Bucolics” and the title poem, which strike me as being among the most accomplished things Auden—or anyone—ever wrote.

Reviewing The Age of Anxiety (1947), Auden’s long “baroque eclogue” set in a wartime downtown New York bar with four characters, Quant, Emble, Rosetta, and Malin, who represent Intuition, Sensation, Feeling, and Thought, respectively, Randall Jarrell wrote:

The man who, during the thirties, was one of the five or six best poets in the world has gradually turned into a rhetoric mill grinding away at the bottom of Limbo, into an automaton that keeps making little jokes, little plays on words, little rhetorical engines, as compulsively and unendingly and uneasily as a neurotic washes his hands.

In general it is true that the diagnostician took over, and in the later poems an urbane, benevolent, slightly smug Auden is forever lecturing, warning, or advising his readers. Also, the poems became very long indeed. “New Year Letter” (1941), “For the Time Being” (1944), and The Age of Anxiety might be rated partial successes. “For the Time Being” (subtitled “A Christmas Oratorio”) began life as a libretto for Benjamin Britten and has good bits—the wise men, the narrator—as well as long, indigestible passages, particularly Saint Simeon’s meditation:

By Him is dispelled the darkness wherein the fallen will cannot distinguish between temptation and sin, for in Him we become fully conscious of Necessity as our freedom to be tempted, and of Freedom as our Necessity to have faith…

The reader’s ability to finish it might depend on their own feelings about Christianity.

The Age of Anxiety is virtuosic in places, full of verbal energy and rhythm and documentary details (“Near-sighted scholars on canal paths/Defined their terms”) but is overextended, and all four characters sound both a lot like Auden and, thanks to the insistent Anglo-Saxon alliteration, like no one who’s ever lived. (“Muster no monsters, I’ll meeken my own…./You may wish till you waste, I’ll want here…./Too blank the blink of these blind heavens.”) The unnaturalness of the language begins to grate.

“New Year Letter” (1,707 lines of rhyming tetrameter) has many brilliant passages, particularly when it harks back to Auden’s lost landscape of the Pennines, though the liveliest thing about it might be its notes, written in doggerel and free verse and prose anecdotes. In some ways it’s a tour de force, attacking ideas of nationalism and using the American polyglot argot, while frequently demonstrating a clipped English restraint and clarity:

However we decide to act,

Decision must accept the fact

That the machine has now destroyed

The local customs we enjoyed,

Replaced the bonds of blood and nation

By personal confederation….

For the machine has cried aloud

And publicized among the crowd

The secret that was always true

But known once only to the few,

Compelling all to the admission,

Aloneness is man’s real condition,

That each must travel forth alone…

Auden witnessed the worst of nationalism and felt it his moral obligation to be alienated from the crowd, the mob. Did he succeed in uncoupling nationalism from poetry? Eliot, in “The Social Function of Poetry,” wrote that “no art is more stubbornly national than poetry,” and Yeats’s entire project was to create a nation, a unifying myth for Ireland—from the Celtic twilight poems and Cathleen ni Houlihan to one of his final poems, “Cuchulain Comforted.” He wanted “an Ireland/The poets have imagined.”

Auden’s response to this kind of thinking can be discerned in his elegy for Yeats:

In the nightmare of the dark

All the dogs of Europe bark,

And the living nations wait,

Each sequestered in its hate…

His reply to becoming the poster boy for a certain kind of Englishness was to up sticks and move to New York. (He told his friend Louis MacNeice in 1940, “An artist ought either to live where he has live roots or where he has no roots at all.”) Nationalism to Auden was akin to patriotism, which was akin to warmongering, and he shrugged off the necessity of speaking for or to a national audience. More interested in a relation of intimacy, he had no time for grandstanding.6 Mendelson wrote of him in these pages:

A writer who addresses a plural audience claims to deserve their collective attention. He must present himself as the great modernists—Yeats, Joyce, Eliot, Pound—more or less seriously presented themselves, as visionary pioneers and cultural authorities, artist-heroes setting an agenda for their time and their nation. In contrast, a writer who addresses an individual reader presents himself as someone expert in his métier but in every other way equal with his reader, having no moral authority or special insight on anything beyond his art.

Auden can be boring, and he can be thrilling, but it nearly always feels like he is talking to you, an individual sitting beside him at high table or at a bus stop. He doesn’t present himself as one of the great visionary pioneers but as a gossipy equal, albeit one endowed with a preternatural facility for language. What may have begun as a way of writing truthfully within the strictures of public life—i.e., writing to a “you” in order to avoid gendering the love object—became for Auden a creed, a tenet. And many poems open like conversations. The tone might be dramatic or funny or confidential, but it’s always chatty: “Looking up at the stars, I know quite well/That, for all they care, I can go to hell”; “A lake allows an average father, walking slowly,/To circumvent it in an afternoon”; “I know a retired dentist who only paints mountains.”

Of the great poets of the twentieth century Auden is the most aware of the danger of “greatness,” of self-presentation as a cultural authority, and where that path can lead: to Yeats’s nationalism or even Pound’s fascism. In “The Composer,” Auden’s depiction of the poet’s job shows both his conviction of poetry’s vital connective work and his understanding of how ludicrous and grubby and unsystematic the work actually is: “Rummaging into his living, the poet fetches/The images out that hurt and connect.” That “rummaging” suggests something decidedly disorderly, someone scrabbling around in the common life. For Auden, “perfection, of a kind, was what” the ideologically committed, the tyrants, were after. Auden lived in the real world of retired dentists and average fathers, where we—if we’re lucky—live too.

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle

-

1

See Fintan O’Toole’s review in these pages, October 22, 2015. ↩

-

2

He is always described, and self-described, as homosexual, though for several years in the 1940s he had a sexual relationship with a woman, Rhoda Jaffe, and brief affairs with women at other times in his life. ↩

-

3

Mendelson reproduces some of Auden’s explanatory diagrams to Isherwood—for example, about his ars poetica, The Sea and the Mirror—though he doesn’t include the extraordinary “comprehensive chart” of antitheses Auden constructed while teaching at Swarthmore and writing The Sea and the Mirror, which can be found in Later Auden. ↩

-

4

Auden discovered Freud at thirteen, according to Mendelson’s biography, “when his father began using the new psychology in his school medical practice.” All his life the poet argued with and borrowed from Freud, becoming, perhaps, the first major poet to use modern ideas about psychology in his work. According to the Cambridge Companion, “From adolescence he would startle or bully his friends with Freudian diagnoses.” ↩

-

5

He had been rejected by the US Army in August 1942 on medical grounds, because of his homosexuality. ↩

-

6

When he felt he had to, he took political and moral stands effectively and quietly. See Mendelson, “The Secret Auden,” The New York Review, March 20, 2014; and “Auden and No-Platforming Pound,” nybooks.com, February 27, 2019. ↩