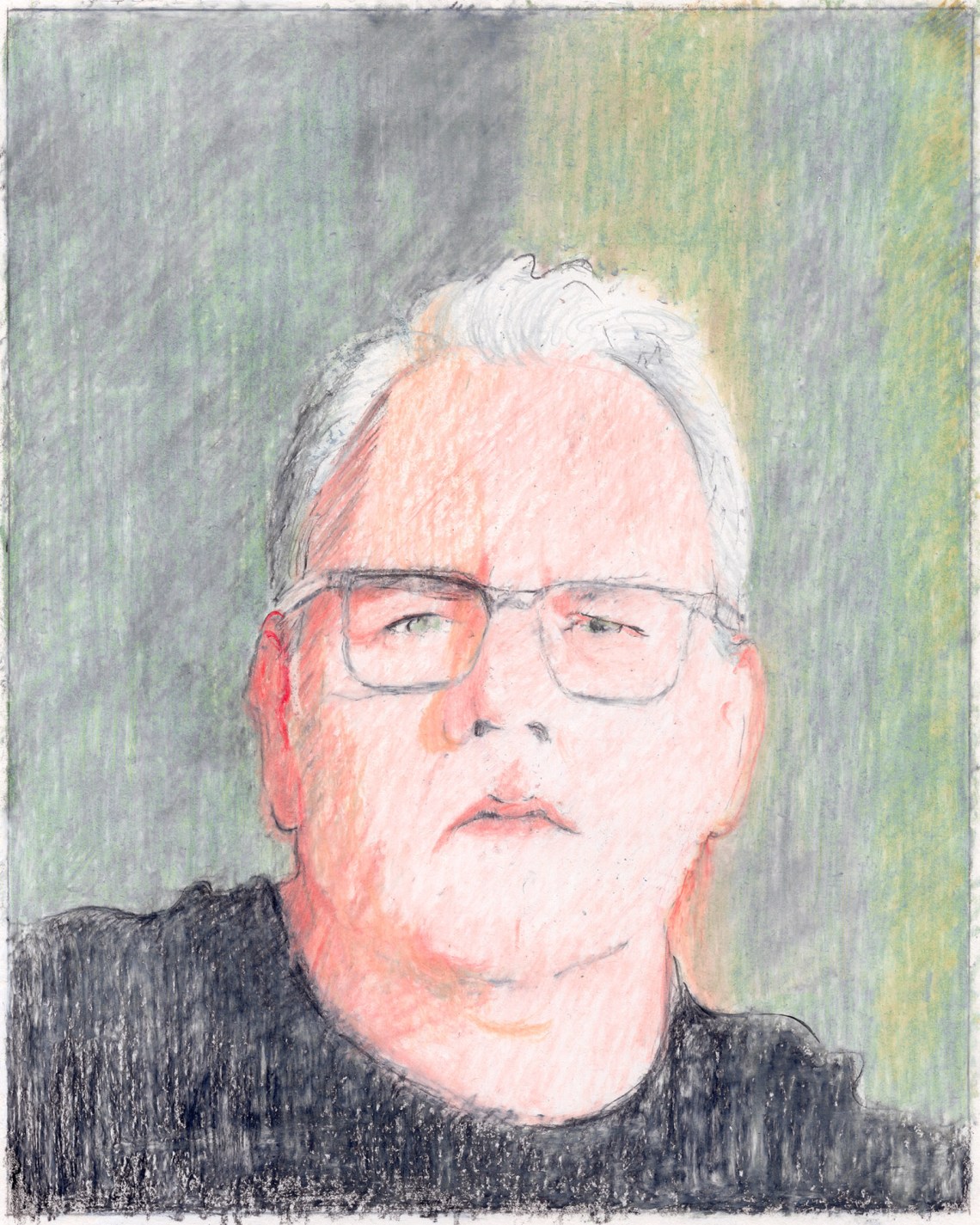

Bret Easton Ellis first saw the Paul Schrader film American Gigolo in February 1980, the month it opened, when he was fifteen years old. He has since seen it more than thirty-five times. “Looking back,” he wrote in the essay collection White (2019), “the impact American Gigolo had on me is impossible to tally.” Many of us were permanently marked by the culture we consumed at fifteen—or ennobled, or enlarged, in some cases even perverted or ruined, if we were unlucky or foolish enough to imprint on the wrong object. What American Gigolo handed Ellis was a loaded sensibility. It had to do with masculinity and sex and Los Angeles and the way that Richard Gere’s sad, blank, beautiful Julian—“less a character than an idea”—seems to elude definite categories of gay or straight, how he “just exists, floating through this world, an actor.” There is a plot in American Gigolo, in which Julian is framed for murder, but what impressed Ellis was the mood and style and surface. It was an early encounter with what he calls “the dream.”

Still, when you’ve sat through a movie three dozen times you get to wondering about it. Ellis’s new idea, which he mentioned in January while introducing a screening of American Gigolo in New York City, is that actually, Julian isn’t framed. That he did commit the murder. It’s not surprising that Ellis would be more interested in perpetrators than so-called victims. He has never written a character who is blameless or pure of heart. His novels are filled with beautiful actors in nightmarish dreamscapes who seem innocent but are revealed to be guilty. (At other times they are only guilty in their own imaginations; the dream is nothing if not ambiguous.)

“Many years ago I realized that a book, a novel, is a dream that asks itself to be written” is how his new novel, The Shards, his first in thirteen years, begins. It is narrated by Ellis’s alter ego, a fifty-six-year-old writer named Bret, and is, as Ellis has described American Gigolo, “a kind of sunlit neo-noir, heavy on dread, heavy on menace.” The dream is a place, Los Angeles, and it’s also a time, the early 1980s. Bret is a senior at Buckley, the elite prep school Ellis himself attended. His parents have gone to Europe for three months, leaving him in the care of the mostly absent housekeeper. He drives his Mercedes to school and sometimes borrows his mother’s Jaguar. He is best friends with the homecoming king and queen and dates Debbie Schaffer, the daughter of a Hollywood producer and the hottest girl in the class. He’s also secretly gay. He’s spent much of the summer in the bed of a classmate, a lonely, green-eyed stoner named Matt Kellner—“my first love.”

Bret listens to bands such as Icehouse and Ultravox (he especially likes the song “Vienna,” with its soaring, mournful refrain, “This means nothing to me”) and spends weekends at parties or the movies, or in his room working on the book that will one day become Ellis’s first novel, Less Than Zero (1985). At night, to help him sleep, he takes Valium supplemented with heroic doses of marijuana. The reason he can’t sleep is that he suspects that a handsome new student at Buckley, Robert Mallory, is really a serial killer known as the Trawler, who has been kidnapping and mutilating teenagers. When Matt is gruesomely, floridly murdered, Bret is the only one who cares.

Buckley; Less Than Zero; references to Todd, Ellis’s real-life boyfriend; mentions of vacations with Jay McInerney—from the beginning, The Shards is playing a long game with truth and fiction. We first met Bret, or a looking-glass version of him, in Ellis’s novel Lunar Park (2005), when he was coming down from the trip of publishing American Psycho (1991) and Glamorama (1998). At that time “Bret” seemed like a solution to the problem of Ellis’s celebrity, specifically how celebrity splits a person. Ellis had become too famous—and too interested in his fame—to do anything but make it the subject of his fiction. But where Lunar Park treated Ellis’s biography like a piece of taffy, something to stretch out and play with, The Shards earnestly buttonholes the reader, like a horror movie that trades in being a true story: “I had to write the book because I needed to resolve what happened—it was finally time.”

The need to resolve and the urge to confess are related. (The desire to spill one’s guts will have extra meaning for a writer so preoccupied with innards.) The Los Angeles of The Shards, like the Los Angeles of American Gigolo, conceals a horrible, hidden reality of violence. As Bret put it in Lunar Park, “There was another world underneath the one we lived in. There was something beneath the surface of things.” But reality for Ellis is as slippery as a pool of blood; it is not reliably real. There’s a serial killer in Lunar Park, but he’s copying the plot of American Psycho, in which a status-obsessed Wall Street banker named Patrick Bateman may or may not commit a number of nauseatingly described, extravagantly sadistic murders; meanwhile a demon is haunting Bret, appearing in the guise of a hairy, hungry thing from a story Bret wrote as a little boy. There is a megalomania at play here, a belief in the writer’s powers of creation, but Ellis also understands that the things we make make us. Whatever fear or anxiety readers felt about American Psycho—the book was widely banned, and Ellis received numerous death threats—was nothing compared to how it made Bret feel. Writing itself—what we put into the world—is the source of horror. Just doing it makes you guilty of something.

Advertisement

Ellis published Less Than Zero when he was a twenty-one-year-old student at Bennington College. Its cultural impact is hard to overstate. The book is narrated by Clay, a freshman at New Hampshire’s Camden College (a thinly disguised Bennington), who is back home in Los Angeles on a break. Clay drives around, does drugs, goes to parties, and remembers his dead grandparents. He sees his therapist and lends money to a friend—the word suggests a degree of warmth and intentionality utterly lacking in his world—named (in a nod to American Gigolo) Julian. But Julian is a drug addict in debt to a pimp, and the only way for Clay to get his money back is to go with him to the Saint Marquis hotel, where a customer has requested two boys—one to have sex with, and one to watch them:

And in the elevator on the way down to Julian’s car, I say, “Why didn’t you tell me the money was for this?” and Julian, his eyes all glassy, sad grin on his face, says, “Who cares? Do you? Do you really care?” and I don’t say anything and realize that I really don’t care and suddenly feel foolish, stupid. I also realize that I’ll go with Julian to the Saint Marquis. That I want to see if things like this can actually happen. And as the elevator descends, passing the second floor, and the first floor, going even farther down, I realize that the money doesn’t matter. That all that does is that I want to see the worst.

Sensationalism had been done before, but Ellis made it new by cloaking it in cool, hard, gleaming prose—Stephen King by way of Joan Didion. The idea is an old one: that beneath the surface of the dream factory—the city of Los Angeles, the life of privilege and celluloid—is hell, and the only way to get out of hell is to not care about anything, to become numb to the pain of others and your own pain. Clay can’t care, about Julian or anyone else, because if he did, he would never escape, and escape is the only alternative to death in Less Than Zero. But Clay is not indifferent. He wants to look, and he has to. Only when he knows what’s there can he leave it behind.

Ellis’s work posits an inevitable relationship between wealth and the desire to “see the worst”; money creates a frictionless existence that demands to be jolted with reality. But what will do it? Inequality isn’t “the worst” in his work; neither is losing a job or your mind or being diagnosed with a fatal illness or any other form of common unhappiness. Death itself isn’t even enough. The secret he buries beneath the surface is a frenzy of violence, the deranged exercise of power of one body over another. Less Than Zero descends into a snuff film and the gang rape of a child. American Psycho is infamous for its depictions of torture, dismemberment, etc. (The Shards does stuff with pets.)

One problem with wanting to see the worst is that you never get there; as Edgar in King Lear knows, “The worst is not/So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’” Another is that Ellis’s desire to see the worst is so all-consuming that it blinds him to anything else. He has a once-in-a-generation talent for conjuring dread and disgust and exposing them as the consequences of a sick, hollow, and narcissistic culture; he’s also funny. But the truth that lies beneath the surface of the world is not that we are depraved authors of Boschian nightmares; it’s that our Boschian nightmares exist alongside acts of love, compassion, faithfulness. Ellis’s stark and unsentimental moral vision is blind to half of human truth, and in this way has remained as childlike as the innocence it wants to dispel.

Advertisement

The Shards stages the desire to see the worst quite literally, when Bret goes to Matt’s house after his death and Matt’s father shows him the photographs of his son’s defiled body. These images split Bret’s life in two:

The secret story about Matt was my loss of innocence, my first moment of adulthood and death, and I never moved through life again unaffected by the trauma this caused, everything changed because of it, and, even more painfully, I realized—and this was the truer, starker loss—that there was nothing I could do. This was life, this was death, nobody cared in the end, we were alone.

The Trawler considers himself an artist. He describes the grotesquely desecrated bodies of his victims as “treasures” or “alterations.” (Before killing someone, the Trawler also breaks into his or her home and rearranges the furniture. This Manson Family–style “creepy crawling” also takes place in Lunar Park and Imperial Bedrooms, from 2010.) I think Ellis wants us to understand The Shards as an alteration of another kind. Yet it’s not quite right to say that Bret was entirely innocent before. Like Clay, Bret came to Matt’s house because he wanted to know more; he wanted to see the worst, he just didn’t know what it was. I would say more about this, but I can’t. Whenever I come to a passage of explicit violence in Ellis’s work, I try to skip ahead. It doesn’t work; my vision always snags on a line that then persists in my mind in the form of intrusive, disturbing thoughts. (Do I want to see the worst, or don’t I?)

Ellis’s essay about American Gigolo is less laconic than my quotations above may have suggested. Here is the full sentence:

Looking back, the impact American Gigolo had on me is impossible to tally, and it’s not as if this is a great film—it’s not, and even its director agrees—but in the way it changed how we look at and objectify men, and altered how I thought about and experienced LA, its influence was vast and undeniable.

This sounds like a spoken monologue because it is. The essays in White first took form as texts that Ellis read aloud on his podcast, as did The Shards. Apparently, like a modern-day War of the Worlds, the podcast so seduced listeners with its veneer of veracity that they became convinced that all the events in the book were true.

It is not easy to write narration that reads like spoken language, but by translating from one medium to another, Ellis has backed into something interesting. He has always tended to “lean toward” (his words) long run-on sentences, but The Shards indulges them to excess, one flowing to the next, to hypnotic effect. Some of them run away like the last rays of sunset on a darkening ocean, and others circle, manically, as if covering a set of tracks. They pull the reader in, creating a sense of intimacy and complicity in a world that otherwise wants to deny both.

There is a compulsiveness to the narration of The Shards, an exhaustive level of information—who sat with whom at the lunch table, who looked at whom at the homecoming game—that is engrossing and ultimately has a purpose. Bret has to keep talking, telling every single thing that happened, from every angle, to sew the reader more tightly into his point of view, his version of the truth. Long exchanges of dialogue shore up the pretense of objectivity. The point is control. (There is also an “unedited” version of the book available on Ellis’s Patreon page that apparently contains an additional 90,000 words, which suggests, at the heart of the novel, a Borgesian desire for a map as detailed as the territory.)

One of the things that makes a novel different from a film is that every reader is free to picture the events in her own way. No two people will “see” the same face or room or light falling on the water at just the same angle. (Even if the language is clichéd, yielding stock images in the mind, there are many different stock images to choose from.) When text becomes image, it gets fixed, determined; there is one face, one hue, one set of props in the room. The freedom is reversed: we now all see the same face, but can describe it in different words. Bret’s paranoid and exhaustive descriptions, by not leaving any space for the reader’s imagination, make the book feel like a film we are watching.

Ellis tells us what Bret is thinking but, more importantly, he puts us in Bret’s gaze. We notice what Bret notices, and what Bret notices most of all are bodies:

Robert cannonballed into the pool and swam sloppily to the shallow end, where he stumbled up the steps and padded over to the diving board, completely wet and naked, and I homed in on his tight, smooth ass and I was suddenly unable to breathe.

Cannonballed, swam, stumbled, padded, and, most importantly, homed—everything is motion, the camera moves across the pool following Robert until it zooms in, holds, so Bret can find the breath to keep talking.

It’s not enough for The Shards to show us things in motion; the sentences ask us to move with them: “I parked on the street, jumped out of the car, unlatched the side gate, and walked the pathway to the backyard directly to the pool and the guesthouse beyond it.” There is no purpose to narration like this except to make sure the reader is with Bret, accompanying him, walking next to him, seeing what he sees when he sees it, entirely controlled by his direction. In this as well as its long, wordy dialogue, The Shards reads as if Bret were watching his own interiority through a screen and writing down everything he sees. (At one point he describes his point of view on a room as “my tracking shot.”) Or maybe the style is Ellis’s comment on retrospection—not that life is a movie, but that memory is:

The opening of “Rapture” by Blondie was playing as we moved down the entrance hall, where only a couple of bare lightbulbs illuminated a concrete floor and Pepto-Bismol-pink walls, the paint peeling away in great patches of black and silver, and Junior, a tall, thin Jamaican wearing a black suit with a white shirt and a black tie and a porkpie hat, was sitting on a high wooden stool and hugged Debbie while the dreamily ominous first verse of “Rapture” played out softly past the doorman—I remember this so clearly and I remember looking behind me to see if anyone was following us down the hallway.

The passage is heavy on color and visual detail but, more than anything, movement. Even the paint is in motion, “peeling away.” We move (we don’t walk, amble, or dawdle; we move, as if impelled by someone or something else, some external force) down the hall with Bret, smoothly taking it all in. If you know “Rapture,” you can hear it, twice, pulling Bret closer to the door. If you don’t, you’ll miss an important emotional cue. You’ll have the sense of motion and the idea of something “dreamily ominous.” But you won’t hear the synthesizers tolling, or the voice, high and breakable as glass.

Whether it’s Patrick Bateman in American Psycho talking about Whitney Houston or Clay thinking about the Beach Boys, Ellis’s characters often listen to and comment on music. His novels are soundtracked to an unusual degree. Or perhaps it’s better to say that they work like mixtapes; the references create an atmosphere. Bret lives in an exclusive world of codes and style, and doesn’t much care who is left out. It’s not going too far to say that “in” and “out” are everything in Ellis’s work. Is the anomie inside Clay or outside of him? Do the events of American Psycho occur out there in reality or only in Patrick Bateman’s mind? There’s something terribly literal about where Ellis takes this problem—serial killers turning bodies inside out, making “alterations” of one kind or another.

Music helps us hear the atmosphere, and it helps Bret write, too. He explains that while working on the book he drank heavily, took Xanax and Ativan, and watched old music videos on YouTube. He discovered that the songs don’t mean what they once did. He thought they were about freedom, but they’re really about “desperate desire and rejection and running away.” He thought they represented “a child who became a man,” but now that he is fifty-six, they represent “a man who stayed a child.”

To stay a child, frozen in time, is a typical trauma response, and The Shards, in several ways, is a novel about trauma. There is, first of all, Bret’s seeing the photographs of Matt Kellner’s body. But even putting those aside, Bret is frequently dissociated. He feels “numb” and also speaks of being “an actor.” He calls the role he plays “the tangible participant.” Whenever anxiety threatens to puncture his stoned haze, the tangible participant tries to keep him focused on playing the part of the normal kid who isn’t obsessed with the Trawler, to soothe him with a reminder that “none of this is real.”

Bret’s real trauma isn’t seeing the photographs of Matt. It’s his sexuality. “I had no stakes in the real world—why would I?” he writes. “It wasn’t built for me or my needs or desires.” Bret has his heart broken first by Matt (“You think we’re gonna be boyfriends? Are you fucking crazy?”), then by another classmate, Ryan Vaughn. He is in love with his friend Thom Wright and angry that this desire can’t be reciprocated. At a climactic moment in the book, he has an explosive encounter with Robert Mallory. But Robert doesn’t stab him. His weapons of choice are seduction and humiliation:

I looked up at his face and the sexy grin was gone and he pushed back and sat on the edge of the bed and then looked down at me and with a faint trace of disgust wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and muttered, “Fucking faggot.” And then, “I knew it.”

Teen heartbreak always feels like life and death, but in The Shards it literally is. There are probably a dozen pages of explicit violence in the novel, but every paragraph is humid with adolescent desire and the fear of discovery. Bret is an obsessive observer of his environment and peers, and much of the terror of the book unfolds as a forensic accounting of social dynamics. He sees others because no one can see him—or so he thinks. But the point remains that the paranoia of the novel is the paranoia of the closet. Bret can’t talk to anyone about Matt’s death because no one knows, or is supposed to know, that he knew Matt at all. Matt’s murder becomes, in the novel’s dream logic, the expression of sexual guilt.

So far, so traumatized. (Not that Ellis would agree. In a recent interview he claimed that The Shards explores gay relationships “a little bit,” which is like saying that American Psycho is “a little bit” about Wall Street.) But to get the full picture of what Ellis is doing with trauma, it helps to look back at White, a book of screeds against liberal “snowflakes,” “micro-aggressions,” and the “rage machine” of the political left. In White Ellis remembered reading horror novels as a child and being fascinated, at age seven, with Thomas Tyron’s The Other, especially its pitchfork death scene, which he read over and over, trying to understand it “on a technical level”—“how the author linked the words up to give this scene its charge.” He loved horror movies, too, and insists that he and his peers weren’t “wounded” by repeated viewings of The Omen at age eleven; on the contrary, “it probably made each of us less of a wuss.” In other words, Ellis isn’t a traumatized person traumatizing his readers; he is dispensing benefits as salutary and bracing as a plunge into cold water. If you do feel traumatized, you should work that out, preferably in private:

This widespread epidemic of self-victimization—defining yourself in essence by way of a bad thing, a trauma that happened in the past that you’ve let define you—is actually an illness. It’s something one needs to resolve in order to participate in society, because otherwise one’s not only harming oneself but also seriously annoying family and friends, neighbors and strangers who haven’t victimized themselves.

The events of The Shards are traumas by any measure of the word. It’s as if Ellis, annoyed at a culture that finds injury everywhere, has written this book to up the ante, to show us all what real trauma is. But then he trolls the trauma plot by casting doubt on Bret’s story, by showing that Bret is not the good detective, by suggesting, in the end, that Bret is culpable for certain horrifying events. He’s not a victim. Even when Bret is coerced into sex with Debbie’s father in a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Bret insists that he, an underage teenager, is responsible. “You did this to yourself,” he says to his reflection in the bathroom mirror. “You wanted to come.” It’s a conversation with the reader. You did this to yourself, I hear him saying. You wanted to read it.

Perhaps the trauma that is hitting Bret hardest has to do with one that everyone must eventually face: getting old. At the end of the introduction, Bret, in the present day, writes about buying a reproduction of Images, the 1982 Buckley yearbook:

I was haunted by the fact that out of the sixty seniors from that class of 1982 five were missing—the five who didn’t make it for various reasons—and this fact was simply inescapable: I couldn’t dream it away or pretend it wasn’t true.

Bret is as captivated by his youth as Ellis himself, who, forty years on, is still working through the success of Less Than Zero. But while his last novel, Imperial Bedrooms (2010), the metafictional sequel to Less Than Zero, was an attempt to destroy the characters who made him famous, The Shards is a cry of nostalgia tinged with rage. “Sometimes I dream about Robert,” Bret writes in the final lines of the book. He is “mostly young, and staring at me fixed in that moment of his teenage beauty, a place where he would always reside—he would never age.” The book’s violent deaths may be nothing more than the fantasies of a middle-aged writer searching for an image that can express the shock and horror of his own mortality.

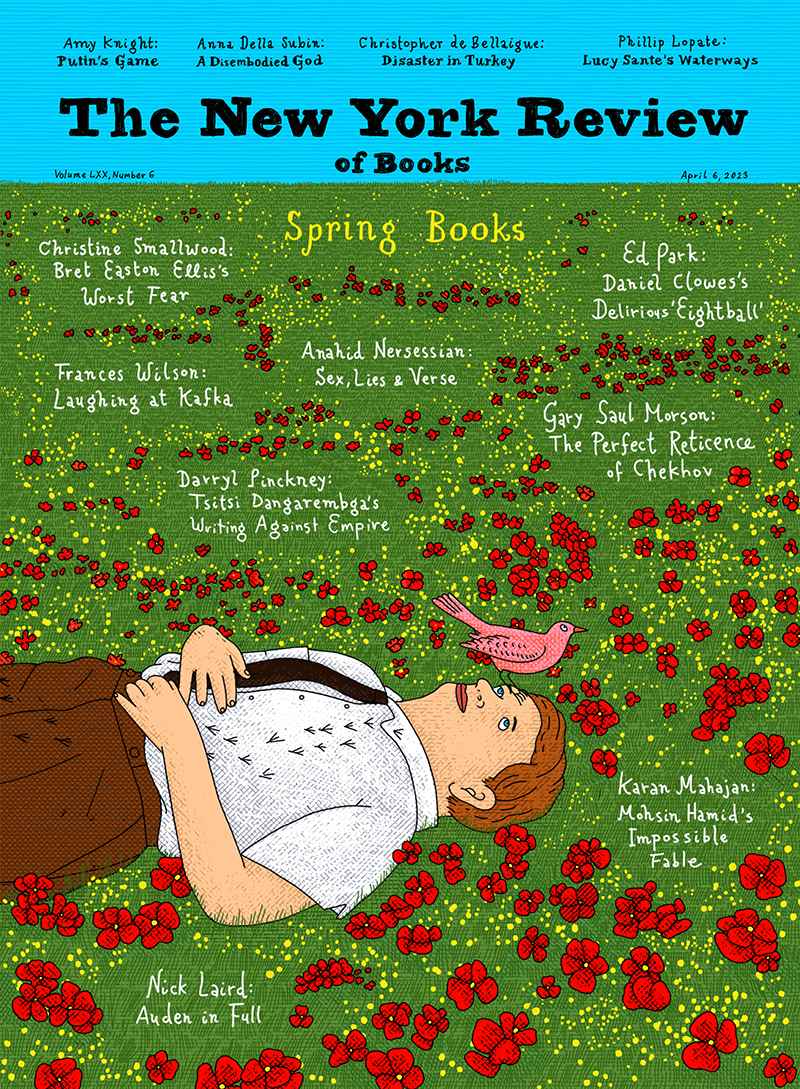

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle