In 1976 John Leonard reviewed Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts for The New York Times:

Those rumbles you hear on the horizon are the big guns of autumn lining up, the howitzers of Vonnegut and Updike and Cheever and Mailer, the books that will be making loud noises for the next several months. But listen: this week a remarkable book has been quietly published; it is one of the best I’ve read in years.

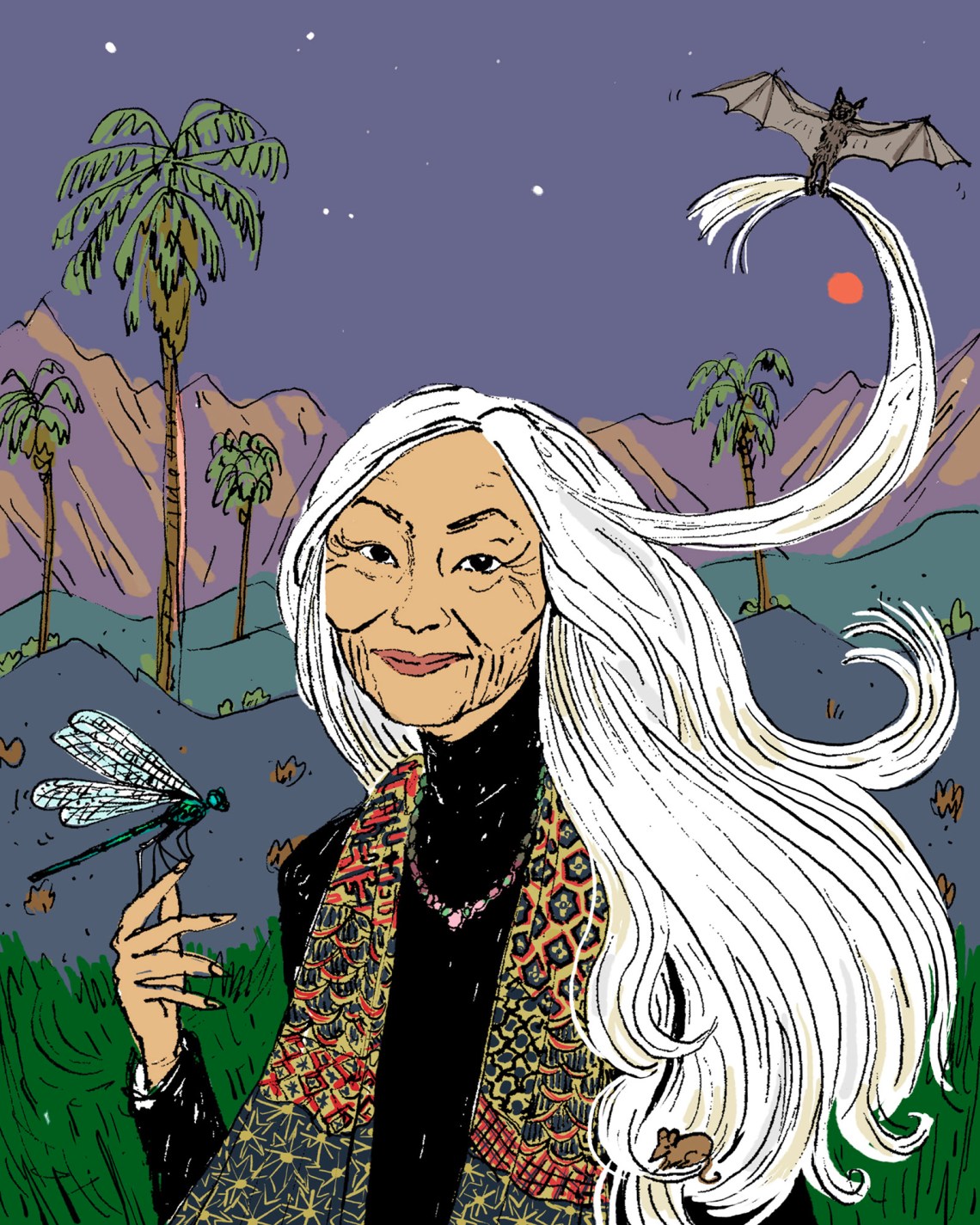

Kingston was about as far from literary stardom as a published writer could be. She was from the West Coast, she was first-generation Chinese American, she taught English and creative writing at a small college in Hawaii, she was a woman. “Who is Maxine Hong Kingston?” Leonard asks. “Nobody at Knopf seems to know. They have never laid eyes on her.” Yet The Woman Warrior hit the literary world with such convincing force that the author went from the obscurest of the obscure to the winner of the 1976 National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction, her book acing out the favorite, Irving Howe’s extensive, learned, and haunting narrative about Yiddishkeit and its fate in America, World of Our Fathers.

Looking back, the award of that prize to an unknown Chinese American woman over the great chronicler of Eastern European Jewish immigration and culture seems to mark the beginning of a change in what Americans noticed and read—as if a baton were being passed from one community, long struggling to assimilate and yet maintain its identity, to another doing the same. The Woman Warrior was an immediate best seller and quickly became part of the academic canon. Chinese immigrants were, like Eastern European Jews, an essential part of nineteenth-century American history, but it was Kingston who introduced them as literary figures, further expanding America’s already extensive immigrant narratives. An entire generation of writers has cited Kingston as an influence.

She also introduced a new kind of narrative. The Woman Warrior did not easily fit into the traditional categories of memoir or novel, not even into the broad categories of fiction or nonfiction. Billed as a memoir, her book floated unexpectedly, unapologetically into myth; then, just as unexpectedly and unapologetically, it landed forcefully back on earth. The earth on which her prose landed had long been unexplored, ignored, or simply unknown to the world of big-gun American literature and publishing. No more. Maxine Hong Kingston was now a howitzer herself.

The Woman Warrior appeared in the midst of enormous national upheavals: the women’s movement, the Vietnam War, all the radical cultural changes of the 1960s and early 1970s. It was in some ways very much of its radical time. But even so, the wonder readers felt at Kingston’s writing should not be underestimated. Magical realism was not yet an established literary style. One Hundred Years of Solitude had been published in the United States only a few years before; Midnight’s Children was five years away. Both those books were, in any case, billed as novels, not memoirs. Stylistically, there was no real category for Kingston’s freewheeling handling of time and reality, of legend and childhood memory. In “Cultural Mis-readings by American Reviewers,” one of the essays included in the Library of America’s recent collection of Kingston’s writing, she says:

Now, of course, I expected The Woman Warrior to be read from the women’s lib angle and the Third World angle, the Roots angle…. What I did not foresee was the critics measuring the book and me against the stereotype of the exotic, inscrutable, mysterious oriental.

She did not foresee it and we no longer see it because Kingston is such an American writer in the way that, say, Whitman is an American writer. Her work is original and shocking and deeply personal, and like Whitman she created her own America, a place she saw, so accurately, so fully, around her.

Her work has aged well. The earlier quibbles—memoir or novel; immigrant reductionism or exoticism—disappear the minute you open this new collection, which includes The Woman Warrior and Kingston’s second memoir, China Men (1980); her novel Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989); and a selection of her shorter works, some previously uncollected. Tripmaster Monkey is a fierce, funny, but rather tiring adventure tale set in the 1960s of a poet recently graduated from UC Berkeley, and it feels very much of that time. The Woman Warrior and China Men, in contrast, have a timeless quality and are still as startling as they were the first time around, just as fresh, as beautiful, as horrifying, bursting with myth and fantasy and nagging reality.

In The Woman Warrior, that nagging reality has as much to do with being female as with being an immigrant. The daughter in the book does not always say much, but she listens and she hears the meanings of words. “There is a Chinese word for the female I,” she tells us, “which is ‘slave.’” Power is not just something found in the legends of mighty women like Fa Mu Lan, the mythical warrior who disguised herself as a man (familiar now from the Disney movie Mulan); it is expressed in the telling of these legends, which Kingston calls “talking-story”:

Advertisement

When we Chinese girls listened to the adults talking-story, we learned that we failed if we grew up to be but wives or slaves. We could be heroines, swordswomen…. Perhaps women were once so dangerous that they had to have their feet bound.

Each night the mother tells bedtime stories that “followed swordswomen through woods and palaces for years,…her voice the voice of the heroines in my sleep.” Only later, years later, does her daughter realize “that I too had been in the presence of great power, my mother talking-story.”

The mother Kingston gives us is full of contradictions. With her husband off working in New York City, she attends a Western-style medical school in China and returns to her village, where she becomes a successful midwife. But once she joins her husband in the US, she works in the laundry he opens in Stockton, California. She never praises her children—a way of protecting them, she later explains to her daughter. She badgers the family to eat, eat, eat. She invites potential suitors to dinner against her daughters’ wishes. She is cold, dismissive, withholding, and undermining. She talks story, but some of those stories are of families back in China selling their daughters. She uses expressions from the old country like “When you raise girls, you’re raising children for strangers” and “Feeding girls is feeding cowbirds.” Even when she is eighty and no longer needs to work, she insists on going out to the fields to pick tomatoes. The woman warrior, Kingston suggests, appears in many guises.

China Men, a sprawling story of the men in Kingston’s family, is a brilliant, moving history of America, and something like a many-charactered Victorian novel. The writing is sterner, more attentive to detail, and at the same time more outgoing, broader, than the prose of The Woman Warrior. Kingston’s gift of allowing particularity to hum with universality reverberates through China Men. It’s an astonishing book.

Kingston begins with a tender but slightly ominous memory of her father:

Father, I have seen you lighthearted: “Let’s play airplane,” you said. “I’ll make you a toy airplane.” You caught between your thumb and finger a dragonfly…. I saw that the wings were networks of cellophane.

The almost pastoral vision of the city of Stockton continues with a description of the walk home from the family’s laundry each night, again with Kingston’s gentle but unmistakable tinge of the portentous:

On summer nights, when we picked new routes home…crickets covered the sidewalks and the lighted windows. Bats flew between the buildings, and some got hit by cars; we examined them, spread their wings, looked at their teeth and furry countenances.

The insects, the bats, the warm summer night—we could be with any family at any time in any small city. But this family arrives home to swat the moths on the front porch while joyfully crying out, “Hit-lah!”: “We killed Hitler moths every summer of The War. It was interesting to grow older and find out that only we called them that, and outside the family, things have other names.”

The names and words that live inside or outside a family reflect the immigrant’s dilemma. Kingston did not learn English until she went to school. Her father had been a poet, a scholar, and a teacher in China; in Stockton, before the laundry, he managed an illegal gambling parlor where people bet on words. Instead of pulling a series of numbers from a barrel, the Chinese gamblers pulled a series of words:

You had to be a poet to win, finding lucky ways words go together. My father showed me the winning words from last night’s games: “white jade that grows in water,” “red jade that grows in earth,” or—not so many words in Chinese—“white waterjade,” “redearthjade,” “firedragon,” “waterdragon.”

Words—with their shades of meaning, their shape and swoop in Chinese script, their greenhorn pronunciation and punning (Hit-lah!)—have a physical reality. They are as tangible as Stockton’s moths and crickets and bats with their furry countenances and teeth.

Kingston’s understanding of words and their material truth grounds her sometimes elaborate, flowing style. There is little that is merely decorative here; the customs of her father’s village in prerevolutionary China, so foreign, so “exotic” to American eyes, become if not familiar then certainly recognizable as human ways of being in the demanding world: for example, the practice of the bride going to live with the bridegroom’s family—a reminder, and a reason, Kingston suggests, that girls are of such little value there. Daughters are not really members of their biological family; they are destined to leave, to desert and serve other mothers, grandparents, fathers. It is with an almost matter-of-fact explanation of the single word “bridge” that Kingston illuminates a woman’s position in both the family and the village. “Her palanquin was called a ‘bridge,’” she writes of her mother’s marriage. “She would go no more to her parents’ house except as a visitor; the visit a woman makes to her parents is a metaphor for rarity.”

Advertisement

And again, by focusing on a single word, this time “poetry,” Kingston illuminates the challenges her father faces as a teacher. After years of intense study, he passes the prestigious imperial exam and becomes a schoolteacher in his village. Her father—who loved study and learning even as a child, who balanced a book on his plow, who writes verse in beautiful calligraphy, who was deemed a scholar from birth because of his long, elegant fingers—is faced with a classroom full of recalcitrant dolts. Still animated by optimism and excitement, he offers the intractable children what he thinks will be a treat. He presents them with a couplet and asks them to finish the poem: “The word poetry had hit them like a mallet stunning cattle.” They stare at him. We don’t get it, they say. And here Kingston moves us seamlessly into the deepest level, the rhyme and reason, of her work: “‘Take a guess,’ he suggested. ‘Taking a guess is the same as making up a story.’”

Taking a guess, taking a risk, writing a story—these are the wonders Kingston recognizes in her ancestors. The Woman Warrior is a compilation and a celebration of talking-story: tales her mother and other relatives passed down, but also Kingston’s freedom to tell stories as she imagines they happened. The result, even now, fifty years after the book was published, is a sense for the reader of being airborne. Talking-story is freedom.

In China Men, the freedom to speak, to tell stories—the same need for self-expression and spoken narrative—is most explicit in a section devoted to Great Grandfather Bak Goong, who leaves his wife and village for Hawaii. He is recruited by the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society to go to what people in his village call the Sandalwood Mountains to cut sugarcane and make money to send home. The work is grueling, the conditions primitive, the foremen harsh. But what galls Bak Goong the most is that the workers are not allowed to speak during the long, hot, pitiless days in the fields.

After years of this, Bak Goong wakes up with a fever one day and is left behind with the other sick workers:

In his fever, he yearned so hard for his family that he felt he appeared in China. He reached out his arms and said, “Wife. Wife, I’m home.” But she said, “What are you doing here? What are you doing here without the money? Moneyless and bodiless, you better go back to the Sandalwood Mountains. Go back and pick up your money and your body. Go back where you belong. Go now.”

Kingston is as unrelenting here, and throughout her memoirs, as those foremen, which keeps her work free of sentimentality, deviously funny, and impossibly rich. These men, called Sojourners, could be away from their wives and children for twenty years or more. Their homesickness must have been overwhelming. The intimacy of Bak Goong’s wife in the dream, her no-nonsense domestic scolding to her bodiless, penniless husband, is marvelously, absurdly realistic. And Bak Goong’s response embodies the achingly sincere emotions and unpredictable resolutions of so many of Kingston’s characters. In the dream, though Bak Goong tries to talk to his wife, “his tongue was heavy and his throat blocked.” It is only when he wakes up that he knows what he and the other Chinese men silently working themselves sick in the Sandalwood Mountains must do. “Uncles and Brothers,” he tells them, “I have diagnosed our illness. It is a congestion from not talking. What we have to do is talk and talk.”

Bak Goong begins the cure by telling them the story of a king who desperately wanted a son. After many years, a princeling is finally born, and the king rejoices—until he sees that his longed-for male child has “little pointed furry ears like a kitten’s.” Afraid his subjects will laugh at him, the king keeps the prince’s kitty ears a secret for years and years, telling no one and raising his child as a normal boy.

But one day the king “could not hold the secret inside himself any more.” He went to a winter field, dug a hole, and shouted into it, “‘The king’s son has cat ears.’ He shouted until he was empty of his secret.” Then spring arrived and the wind blew through the grass. “The sounds swelled through the summer, enunciated until the people knew for sure what the tall grass and the wind said louder and louder: ‘The king’s son has cat ears. The king’s son has cat ears.’ It grew into a song.”

The day after Bak Goong told the story, the men went out as usual to the fields. But instead of cutting cane, they dug a hole, then

threw down their tools and flopped on the ground with their faces over the edge of the hole and their legs like wheel spokes. “Hello down there in China!” they shouted. “Hello, Mother.” “Hello, my heart and my liver.” …They had dug an ear into the world, and were telling the earth their secrets.

Another Sojourner grandfather, Ah Goong, travels three times to Gold Mountain, as San Francisco was called. Ah Goong is a delightful eccentric. Against every societal dictate, he wants a daughter and tries to exchange his fourth son (Kingston’s father) for a neighbor’s baby girl. He is considered insane by his wife and village. Ah Goong “would have stayed in China to play with babies or stayed in the United States once he got there,” but he was pushed into the Sojourner cycle by his wife. “‘Make money,’ she said. ‘Don’t stay here eating.’”

In 1863, “the Central Pacific hired him on sight; chinamen had a natural talent for explosions.” In one particularly poignant description, Ah Goong is sleeping outside with the other workers when he recognizes stars and constellations from the skies of China:

There—not a cloud but the Silver River, and there, on either side of it—Altair and Vega, the Spinning Girl and the Cowboy, far, far apart…. Pretending that a little girl was listening, he told himself the story about the Spinning Girl and the Cowboy…. They were too happy. They wanted to be doves or two branches of the same tree.

The Spinning Girl and the Cowboy neglect their work, and the Queen of the Sky has to separate them. But once a year the King of the Sky takes pity on them, and they are allowed to meet:

Ah Goong’s discovery of the two stars gave him something to look forward to besides meals and tea breaks. Every night he located Altair and Vega and gauged how much closer they had come since the night before…. The Spinning Girl and the Cowboy met and parted six times before the railroad was finished.

The depiction of Ah Goong’s work building the railroad is some of Kingston’s most powerful writing. The men, each in a basket, were lowered down high, steep cliffs to the point where tunnels would have to be dug. Ah Goong

rode the basket barefoot, so his boots, the kind to stomp snakes with, would not break through the bottom. The basket swung and twirled, and he saw the world sweep underneath him…. Suspended in the quiet sky, he thought of all kinds of crazy thoughts, that if a man didn’t want to live anymore he could just…tilt the basket, dip, and never have to worry again. He could spread his arms, and the air would momentarily hold him before he fell past the buzzards, hawks, and eagles, and landed impaled on the tip of a sequoia.

Instead he grabs a twig, holds himself against the cliffside, digs holes, places his gunpowder in the holes, then lights his fuses: “The men above pulled hand over hand hauling him up, pulleys creaking.” The men did not always get up in time:

This time two men were blown up. One knocked out or killed by the explosion fell silently, the other screaming, his arms and legs struggling…. The shreds of baskets and a cowboy hat skimmed and tacked. The winds that pushed birds off course and against mountains did not carry men.

Ah Goong goes back to China for good after the 1906 earthquake, his gold made into jewelry he presents to his demanding wife.

Kingston understands the intimate bond between exact, eerie detail (that cowboy hat) and grand observations of the ways of the cosmos. She can also embed historical, social observation in a panoramic view:

Across a valley, a chain of men working on the next mountain, men like ants changing the face of the world, fell, but it was very far away. Godlike, he watched men whose faces he could not see and whose screams he could not hear roll and bounce and slide like a handful of sprinkled gravel.

With the spiral of a falling cowboy hat, Kingston observes and upends America’s western myth. With the famous pounding of the golden spike in 1869, when the railroad from the east meets the railroad from the west, she acknowledges and overturns another American myth:

A white demon in top hat tap-tapped on the gold spike, and pulled it back out. Then one China Man held the real spike, the steel one, and another hammered it in.

While the demons posed for photographs, the China Men dispersed. It was dangerous to stay. The Driving Out had begun.

The driving out of Chinese workers after the completion of the transcontinental railroad led to massacres in California, Colorado, Wyoming, Washington, and Oregon. One chapter of China Men, entitled “The Laws,” is simply a list of over a hundred years of America’s exclusionary racist laws aimed at Chinese immigrants. Barred from public schools, forbidden to own the land in the San Joaquin Delta they were filling and leveeing, subjected to “a pole law prohibiting the use of carrying baskets on poles”: the list goes on and on. In 1868, while debating the Nationality Act, one congressman insisted that America should be a nation of “Nordic fiber.” The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was not repealed until 1943. “At this time Japanese invaders were killing Chinese civilians in vast numbers,” Kingston notes. “It is estimated that more than 10 million died.”

The political crimes of the US government cannot, however, tear up those railroad ties laid down by Chinese workers. They don’t fill in the dynamited tunnels. “After the Civil War,” Kingston writes, “China Men banded the nation North and South, East and West, with crisscrossing steel. They were the binding and building ancestors of this place.” They are Kingston’s ancestors, too. Yet the secret words that Bak Goong yelled down the hole in the sugar fields were “I want home.” Home is everywhere in Kingston’s books, and nowhere. Who belongs where? Who, though longing for a village near Canton, is an American? Who, though speaking English and dressing in Western-style suits, will always be Chinese? Who is neither? Who is both? This is, of course, the dilemma of every immigrant population.

What Kingston does is reveal the pain and confusion and determination and, often, the comedy experienced not only by the immigrant Chinese population as a whole, but by individual Chinese men and warrior women, by families living the contradictions of cultures while celebrating the universal continuity of the stars, the seasons, the migration of birds. On the one hand, Kingston writes:

Many men on my mother’s side of the family, even today, even the young men in countries where polygamy has been outlawed, have two wives, two houses, two families. The men in the past had three wives. The first wife, of course, was the important one; the others were “for love.”

On the other hand, there is Kingston herself, a writer rejecting the indignities of both cultures yet compassionate, with uncanny precision, to the people who must endure them.

When her father was struggling to teach the unruly children of his village (I have never read a better description of a classroom out of control),

he yearned for the fields with their quiet surprises, which he had plowed around—the nest with eggs from which he had felt the warmth rise, the big mushroom with nibbles around its crown and the mouse dead underneath, a volunteer lily when the field had been sown to rice.

This is the story Kingston tells with her delicate, microscopic caress, one of longing and impossible sweetness. But always, she says, there is the dead mouse.