I’m in the cabin of a crane, a hundred feet off the ground. My seat is the ultimate La-Z-Boy, an exaggerated captain’s chair out of a sci-fi film. Under the watch of a mechanic named Dylan, who’s employed by the Port of Tacoma and represented by the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, I tug gently on the joystick, jerking us forward and backward along the cables that keep us aloft.

Were I actually a crane operator and not a visiting journalist, I would know how to correct for “feathering” in the wind. Looking through the glass floor, I would steer the rectangular metal grabber to lift a container from the deck of a ship onto a pier, or from the back of a truck onto a dock. I would rely on a second operator to give me signals or trade time with me in my seat, especially on overnight “hoot owl” shifts.

If you live near a port, you may have contemplated such activities while watching a ship piled high with colorful boxes grow larger on the horizon. Or perhaps you are one of the millions of people for whom the pandemic stirred a fascination with logistics. When the Ever Given, one of the largest container ships in the world, got stuck in the Suez Canal last spring, it felt like a metaphor for capitalism during Covid-19.

I grew up not far from this port—Tacoma, like its neighbor Seattle, has always been a marine town—but this is my first time on the premises. To the right of our crane is the Hyundai Courage, a ship that arrived from Busan, South Korea, via Vancouver.1 (Ninety percent of the containers coming through here originate in Asia.) It takes about two minutes for each box, filled with whatever we’ve ordered on Amazon, to be hoisted and set down. From the air, or faraway on land, it all looks like a robotic ballet, free of human exertion.

But there are, in fact, many human choreographers. Besides the cranemen (and occasional cranewomen) overhead, there are lashers who fasten containers to the deck of every ship and slingmen who pull oddly shaped goods—such as logs, bulk grain, and military helicopters—onto shore. Day and night these workers get their assignments through a union-operated hiring hall. In North America, some 100,000 longshore workers belong to a union: the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) on the East Coast and Gulf Coast, and in eastern Canada and Puerto Rico, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) along the West Coast and in Alaska, Hawaii, and British Columbia. Though their numbers are small compared with the two million members of the Service Employees International Union or the million-plus members of the International Brotherhood of the Teamsters, longshoremen are trained in esoteric work that is essential to global commerce. This gives them the unique ability to freeze the economy—when their labor conditions, or those of other workers, so demand.

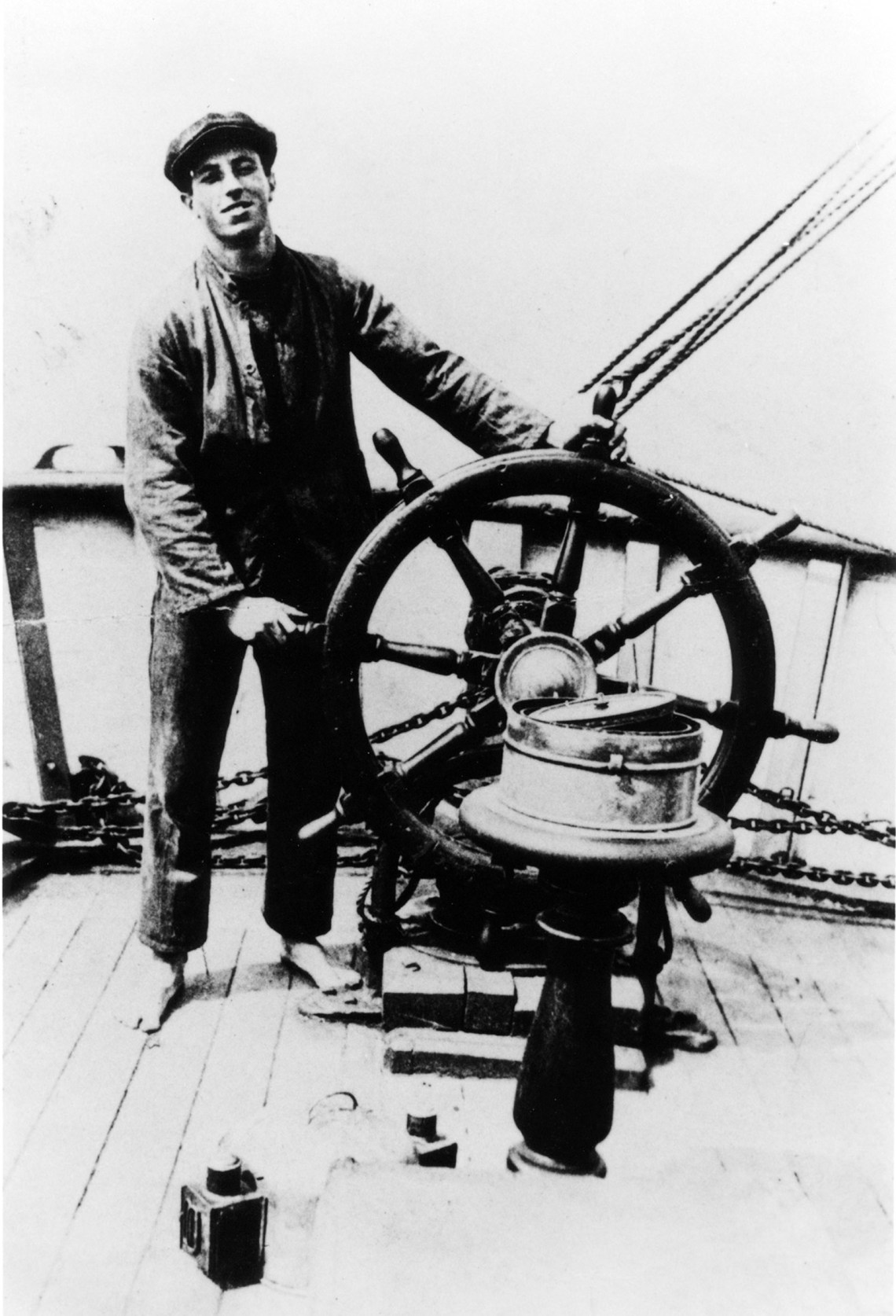

The ILWU in particular is known for wielding its power, and in politically radical ways. It was formed in 1937 as a rebuke to the ILA’s style of unionism, which was top-down and deferential to the shipping companies. Its cofounder and longtime president was Harry Bridges, an immigrant dockworker who became something of a celebrity. In the history of the US labor movement, he is arguably as significant as Walter Reuther, who led the United Auto Workers in taming Detroit’s Big Three, or John L. Lewis, the miner who helped bring millions of disparate people into unions. In the history of the American left, Bridges merits comparison with Eugene V. Debs, Emma Goldman, and Malcolm X. Today he is less well-known than he should be.

A new biography, Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend by the historian Robert W. Cherny, an emeritus professor at San Francisco State University, won’t do much to bring the man to a general audience. With the permission of Bridges’s third wife and widow, Noriko Sawada, Cherny spent decades examining archives and conducting interviews to assemble a definitive account. But he is like a pianist who has sat too long with a sonata: the tingly beauty of the theme has worn away; no flourish survives the overpractice. The book moves chronologically through eighteen chapters, elaborating on a previous biography, Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the United States (1972), which Charles P. Larrowe published while Bridges was still alive. (In the copy I perused at the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies at the University of Washington, Bridges himself wrote, over the title page, “I don’t think much of this book. Too many distortions.”2)

Cherny’s book nonetheless allows us to revisit a monumental twentieth-century life. Bridges the man may not be widely known, but his philosophy of inclusive, democratic unionism imbues much of today’s most ambitious organizing campaigns, from Starbucks and Amazon to the teachers’ unions in Chicago and Los Angeles. The compromises Bridges made as head of the ILWU are just as instructive. As he evolved from rank-and-file incendiary to bureaucrat, he faced criticism for his links to Communists, his growing skepticism of strikes, and his willingness to adopt “labor-saving” technologies. His example prompts us to ask: When is it time for a leader to step down? How closely should labor align itself with a political party? And whose interests should a union represent—those of its current members or the members to come?

Advertisement

Harry Bridges was born in 1901 and christened Alfred, after his father. As he grew up in a suburb of Melbourne, he decided to adopt the name and pro-labor politics of his paternal uncle. Australia was a new country then (at least from Europe’s point of view) and had the highest unionization rate in the world. This was due, Cherny writes, to a strong “system of industrial arbitration” and a “White Australia” policy that prevented the entry of Asian workers and kept the labor market tight. During World War I, Bridges’s beloved uncle died from combat wounds, and young Harry dropped out of school.

In 1917 high food prices led waterside laborers across Australia to rebel. They refused to load certain ships, then walked off the job completely, along with seamen, coal miners, and railway workers. The government blamed this “Great Strike” on the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), with its gospel of direct action and “one union for all.” The strike inspired Bridges, who reviled his first job of delivering eviction notices for his landlord father and later worked as an office clerk, to become a merchant marine. He joined a seafarers’ union as well as the IWW and went to work and organize in New Orleans and Mexico.3 In 1922 he docked in San Francisco, where he decided to stay, at least temporarily.

It was common then to go from seafaring to longshoring, despite the brutal, irregular rhythm of the docks—being on the water wasn’t any easier. In San Francisco, longshoremen lined up outside the Ferry Building, trying to catch the attention, and stay in the good graces, of shipping foremen. This ritualized “shape-up,” Bridges observed, resembled an old-world “slave market.” (It still exists in cleaning and construction. Just visit a Home Depot at 6:00 AM, where immigrant day laborers haggle for work.) The men were induced to join a sham union under the shippers’ control and faced blacklisting for demanding better pay or reporting debilitating injuries. Once, when Bridges was in the hold of a ship, a load of steel fell on him, and he lost a week of work. Several years later his foot was crushed.

He married Agnes Brown, a waitress he’d met on a trip to Oregon, in 1923. During the Depression, he worked day labor jobs and went on unemployment to support her, their daughter, and a stepson. He then returned to the docks and joined the ILA, whose headquarters were in New York. It was “a lousy, rotten, racketeering organization,” Bridges said, but still preferable to no union at all. (By then he had left the IWW.) In 1933, as violent strikes erupted across the US, he and a group of like-minded longshoremen, many of them Communists or fellow travelers, established a new chapter of the ILA, Local 38-79, based in San Francisco. They published a mimeographed newsletter called the Waterfront Worker and committed to eight principles that emphasized “the unity of all workers and the maximum degree of membership control.”

Longshore organizing got a boost from the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act, which included a section protecting workers’ right to organize—and which the Roosevelt administration was willing to enforce. Dozens of new locals formed up and down the West Coast, all the way to Alaska. Bridges and his allies in Local 38-79 pressed for coastal unity and sent organizers far beyond the Bay Area. (In the 1940s they led a remarkable campaign to organize sugar-plantation workers in Hawaii.) At a meeting of the Pacific Coast District of the ILA in 1933, the locals settled on a batch of demands, including maximum hours and a worker-controlled hiring hall. They also wanted a single coastwise contract in order to prevent employers from relocating cargo to ports they perceived to be less troublesome. Bridges had no support from the ILA president, Joseph P. Ryan, who resented this western rebellion.

In May 1934, after months of fruitless bargaining, thousands of Pacific marine workers went on strike. Bridges, who would soon turn thirty-three, led the strike committee and traveled to major port cities to get commitments from longshoremen as well as other workers in the supply chain. Rank-and-file Teamsters truckers, like rank-and-file ILA members, were increasingly at odds with union leadership. The president of one Teamsters local in California dismissed the longshoremen as “radicals of the worst type,” yet his members refused to cross the picket line. Bridges also visited Black churches to seek support from men whose exclusion from the docks made them vulnerable to being recruited as scabs. Cherny quotes from a Black newspaper: “He implored Blacks to join him on the picket line and when the strike was settled, Blacks would work as union members on every dock in the Bay Area and the West Coast.”

Advertisement

Bridges and his fellow unionists found themselves battling “labor spies, strikebreakers, and private armed guards.” Each port was different, but in cities such as Seattle, Oakland, and Los Angeles, longshoremen risked their lives to block replacement workers from the docks. “The city of San Francisco stood on the brink of class warfare,” Cherny writes. “Sentries with bayoneted rifles marched in front of the piers. Machine-gun nests guarded key locations. Tanks prowled the Embarcadero.” Two months into the strike, on a July day that would come to be known as Bloody Thursday (and is still commemorated by the ILWU), two unionists were shot and killed, most likely by the police. Thousands of workers and supporters joined a funeral march through downtown.

Within days the maritime strike blossomed into a citywide general strike. Bridges explained to a crowd of Teamsters “that defeat of the maritime strikers would challenge the entire labor movement,” Cherny writes. In San Francisco, “no taxis or trucks moved on the streets. Movie theaters, barbershops, dry cleaners, bars, auto-repair shops, and most gas stations were closed.” Shippers called for “bloodshed” and local officials panicked; the Roosevelt administration implored all sides to submit to arbitration. Longshoremen returned to work, provisionally, at the end of July. For nearly two months federal officials heard testimony on working conditions and what was needed to guarantee a lasting peace. The final decision, announced in October, was, in Cherny’s words, “a smashing victory” for the longshoremen. The ILA won a six-hour day and a thirty-hour week, a wage increase, “and, most important, control over dispatching.” Union members would run the hiring hall; the shape-up was no more.

Three years later, after experiments in industry-wide organizing and another lengthy strike, the Pacific Coast District, under Bridges’s leadership, broke off from the ILA and formed a new entity: the ILWU. A philosophical divide in the labor movement had by this time become structural: the American Federation of Labor, to which the ILA belonged, was generally conservative and risk-averse, focused on defending what skilled workers already had. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), on the other hand, wanted to aggressively unionize major industries across nationality, race, and job category, and drew many leftists, including Communists, as a result. Bridges chartered the ILWU with the CIO.

The 1934 strike, in its sheer daring, became the foundational event of the ILWU and shaped the rest of Bridges’s life. He and the union were seen as one and the same, which protected him against years of attacks. Between the mid-1930s and the mid-1950s, various federal agencies, at the behest of the shipping companies, put Bridges repeatedly on trial, and the ILWU funded his defense. There were several attempts to have him deported, as well as a prosecution for perjury stemming from his application for citizenship. (Not to mention a vengefully baroque tax case.) The basis was his alleged membership in the Communist Party, which Bridges denied.

Cherny details the strange turns of each trial. At the height of McCarthyism, Bridges was close to a household name. Americans tuned in to news of his legal goings-on, though the evidence, as in so many red-baiting prosecutions, was dubious. Government witnesses bore personal grudges against Bridges or were “‘professional’ witnesses—former [Communist Party] officials who traveled the country testifying against alleged CP members,” Cherny writes. There was ample proof that Bridges admired the party, was close to party officials, and held the same views as the party. But it was as often the case that the party followed Bridges’s lead.

For decades Bridges’s alleged communism was a sensitive topic for the ILWU. If he was, indeed, a party member, hadn’t he put the union at risk and unfairly drawn on its financial and political capital for his repeated defense? Was it red-baiting even to ask the question? Cherny wants to provide a definitive answer. He reviews the evidence from Bridges’s trials, supplemented with new information from Russian archives. What he finds is inconclusive: Bridges probably wasn’t a party member, though he can’t be sure.

It feels like much ado about (almost) nothing, in 2023, when younger unionists attach little stigma to the Communist label. Red-baiting still happens, of course, and radicals are often sidelined, or worse, in more traditional quarters of the labor movement. (Immigrants still must repudiate communism to stay in the US.) But Bernie Sanders–style socialism has helped to normalize various leftisms, and members of the Democratic Socialists of America and the Young Communists League have applied lessons from the 1930s to recent campaigns. After the Amazon Labor Union formed the first-ever union at an Amazon warehouse in the US, on Staten Island, organizer Justine Medina wrote in Labor Notes that the workers had studied Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry, an old how-to pamphlet by William Z. Foster, a general secretary of the Communist Party USA.

What might Bridges’s association with Communists, and the Soviet cause, reveal about labor and politics? He was a committed leftist, but never thought that the ILWU should be above or detached from electioneering. He once said of the IWW, “There comes a time that you can go a little too far with direct action. The IWW philosophy was never to sign an agreement, for example; never to arbitrate; never to mediate; never to consolidate.” Bridges was a New Deal loyalist and a confidant of Frances Perkins, Roosevelt’s formidable secretary of labor and the first woman to serve as a member of the cabinet. (Perkins faced enormous pressure to deport Bridges; according to Cherny, he told her “to do what was necessary to save herself politically.”) Members of the ILWU voted down the line for Democrats.

The signing in 1939 of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a nonaggression agreement between the Soviet Union and Germany, led the Communist Party to oppose US involvement in the war—to the shock of many antifascists. Bridges adopted this position, causing splits within the ILWU and the rest of the Communist-heavy CIO. After Roosevelt died, Bridges and the ILWU executive board fell out with the Democratic Party. They opposed the Marshall Plan, which the Communist Party derided as “American capitalists’ effort to control the economies of Europe,” Cherny writes. When the ILWU backed Henry Wallace, an idealistic but hopeless third-party candidate, over Truman in the 1948 election, the CIO expelled the union.

In 1956 Bridges changed his voter registration to Republican as an act of protest and political theater. “I have always resented the pat conclusion of most Democratic politicians and their labor movement followers that organized labor must stick with the Democrats no matter what,” he explained. His members, meanwhile, stayed steady with the Democrats. The question for unions is the same today: How much to rely on legal reforms and regulations? How closely to hew to Biden?

Cherny, like Larrowe before him, writes admiringly of Bridges’s rank-and-file independence. But he also documents how Bridges grew intolerant of dissent within the ILWU and hung on to the presidency, despite his criticism of the “one man union” model. Contradictions within the union arose in the 1950s, spurred by technological change. The demands of globalized consumption, and shippers’ ambitions, pushed toward mechanization and larger, faster loads. Goods became standardized and stackable: first uniform boxes and cribs, then the container. Cranes and forklifts displaced manual hooks and poles. Fewer men were needed on the docks.

In 1960 the ILWU signed the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement (M&M), a contract that accepted new technologies and reduced working hours in exchange for an annual payout. This fund, Cherny writes, provided for minimum weekly earnings, an early retirement program, and increased death and disability benefits. Was the trade-off worth it? Cherny argues that Bridges and the ILWU underestimated the speed and scope of the coming transformation. There was also the matter of how the union spent its money: in a second M&M, in 1966, the ILWU voted to distribute some $13 million in accumulated funds to registered A men (the most senior workers), instead of saving or reinvesting it for future needs. The historian Nelson Lichtenstein has argued that, as a result of the concessions of the M&Ms, “the ILWU shriveled as longshoring practically vanished from the West Coast occupational landscape.”

What if the ILWU had put those employer payouts toward new organizing or industrial research? It might have prevented the deunionization of warehouse workers, coordinated with the Teamsters to organize port truckers, or embarked on an imaginative campaign in a new region, as it had with the agricultural workers in Hawaii. Could the ILWU have better anticipated, and strategized against, the automation of ports in California? Mechanization wasn’t avoidable in longshoring any more than in car or plane manufacturing, but there are many ways to mitigate harm.

Peter Olney, a retired organizing director of the ILWU, has argued for a renewed “march inland” to where the jobs are.4 Between 1980 and 2010 the number of registered Class A and B longshore workers in California, Oregon, and Washington increased only slightly. The number of workers in marine logistics call centers, warehousing, and trucking, meanwhile, increased between 64 and 600 percent. “Why couldn’t the ILWU represent people doing software development?” Olney asked me. (The current ILWU contract expired last July; members have stayed on the job without striking while their representatives negotiate.)

In 1971 Bridges was seventy years old and still leading the union. He had prevented Louis Goldblatt, its long-suffering secretary-treasurer and a former warehouse worker, from rising to the presidency. Jack Hall, another promising leader, who masterminded the Hawaii strategy, died that year shortly after becoming the director of organizing. The ILWU opposed the war in Vietnam but benefited from “the increase in shipping and concomitant demand for longshore workers,” Cherny notes. There was no refusal to work ships supplying the war effort, as there had been with respect to Nazi Germany, imperial Japan, and Italy during its invasion of Ethiopia. Younger members of the union were energized by the antiwar, civil rights, and student movements, and wanted more from the M&M contract. Between 1966 and 1970 their work hours had fallen dramatically while the freight passing through Pacific Coast docks increased by a quarter. Cherny describes how some members accused Bridges, once a civil rights vanguardist, of discriminating against newer Black members by prioritizing seniority.5

The young rank and filers of the ILWU prevailed, sort of. They voted to strike and stayed off the job (making exceptions for military and perishable cargo) for seven months, until January 1972. It was the longest dockworkers strike in history and worried President Nixon enough that he met directly with Bridges and threatened forced arbitration. Unfortunately for the union, Cherny writes, the strike’s primary win was a work guarantee for A and B men. Bridges never supported the walkout. “The strike weapon should never be used except as a last desperate resort, when there’s no way out,” he said.

Both Cherny and Larrowe have chapters late in their books titled “Labor Statesman,” though Cherny adds a question mark. Bridges led the union for too long, if democratically and without scandal: his members kept voting him in, and he set his own salary “well below that of the best-paid ILWU longshore workers,” Cherny notes. Bridges married three times—Agnes, Nancy, and Noriko—and had four children and one stepchild, but his true beloved, for whom he worked through chronic illnesses and his addiction to pills and alcohol, was the union. Whatever the shortcomings of his latter-day leadership, it’s hard to know how, or how long, he might have prevented job losses. The insularity of the union is the more convincing critique. Bridges’s M&M contracts, in their defensive crouch against technology, put preservation first. It’s something all unions struggle with in an era of declining worker power: how to keep old members happy while bringing in the new. (In 2022 a historic low of 10.1 percent of US employees belonged to a union.)

As measured by his members’ affection, Bridges was a singular leader. He died in 1990, yet dockworkers on the West Coast still refer to him as “Harry” and credit the 1934 strike for their middle-class livelihoods. The union remains left-wing, a reliable partner to peace and racial justice movements. In 2018 members elected the first Black president of the international, Willie Adams. In Tacoma, where Adams started on the docks, Local 23 of the ILWU operates a hiring hall and a credit union across the street.

Late last summer I went to the hall with Tyler Rasmussen, a twenty-seven-year-old longshoreman and member of the union’s Young Workers Committee, to observe the morning “pick.” People of all genders, ages, and races gathered in a large auditorium, making friendly chatter. Jobs were allocated by seniority (Class A, Class B, then newcomer “casuals”) and on the basis of “low man out,” giving preference to people who’d clocked fewer hours. Each group started behind a yellow line, then stepped up, when called, to check in with a dispatcher. Old-timey longshore hooks were displayed in wooden boxes along the wall. Volunteers with the spouses’ auxiliary club served coffee. A portrait of Bridges stared out from the window of the dispatch office.

On Labor Day, which was sunny and cool, I joined Rasmussen and other members of Local 23 for an annual service at the grave of Ralph Chaplin, a polymath IWW organizer who traveled the world before settling down in Tacoma. Chaplin, who died in 1961, is best known for writing the lyrics to the labor anthem “Solidarity Forever.” (“It is we who plowed the prairies;/built the cities where they trade.”) He also designed the anarcho-syndicalist symbol of a caterwauling black cat, spine and tail raised high.

Fifty people from different parts of the local labor movement (age range: Zoomer to ninety) stood in a circle on the grass and took turns introducing themselves. One young man wore an Amazon Labor Union T-shirt; another, a shirt that said “Fuck ICE.” There was excitement about the organizing campaign at Starbucks, the movement to abolish student debt, and the record number of union elections being handled by the National Labor Relations Board. We sang from little red songbooks as an older, bearded guy played a guitar.

The bearded guy was Vance Lelli, a crane operator whose dad led Local 23 for twenty years. “I’m probably the only person here who ever met Harry Bridges,” he told me. Bridges seemed present nonetheless. Nyef Mohamed, a younger member of Local 23, wearing a straw hat, sunglasses, and sandals, spoke of him in the present tense. “For me, Harry is such an important leader, and we’re so lucky to have him involved in the union,” Mohamed said. “He was a young worker when he became a leader of the union, so for me it’s inspiring. I look at myself, the same age, thirty-three years old.”

-

1

A month later, on a trip to South Korea, I visited the Port of Busan and pictured the Courage gliding over the East Sea toward North America. Busan’s port is one of the largest container throughputs in the world and a nerve center of the South Korean economy. ↩

-

2

Both the center and an endowed position in labor studies were established through a grassroots fundraising campaign among ILWU pensioners. One handwritten donation letter from the archives reads, “I owe Harry more than this. I was dead broke with a wife + child to support when I went down to the ‘front.’ The ILWU was a life saver for me.” ↩

-

3

In his Workers on the Waterfront (University of Illinois Press, 1988), the historian Bruce Nelson identifies four reasons for the historic radicalism of seafarers: raw exploitation, rootlessness and transiency, social isolation, and a sense of internationalism born on the seas. ↩

-

4

Harvey Schwartz’s The March Inland: Origins of the ILWU Warehouse Division, 1934–1938 (Institute of Industrial Relations at UCLA, 1978), covers the longshore union’s ambitious attempt to organize transportation, storage, and even food-processing workers in San Francisco. Bridges’s vision for a large industrial union was undermined in part by the Teamsters, which feared losing potential members to the ILWU. ↩

-

5

In Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area (University of Illinois Press, 2018), Peter Cole notes that, despite Bridges’s attempt to set a tone of racial justice from the top of the ILWU, “prejudice flourished in locals where white members were racist or treated the union as a job trust for sons, nephews, and neighbors.” Yet Bridges succeeded in forcing some locals to accept Black members, and in 1965 the ILWU passed a resolution to boycott Alabama cargo in response to events in Selma. ↩