Two recent publications offer a dramatically new approach to the history of Impressionism: Marine Kisiel’s La Peinture impressionniste et la décoration and Le Décor impressionniste: aux sources des “Nymphéas,” edited by Sylvie Patry and Anne Robbins, the catalog of a superb exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris in 2022. They cover the same terrain, focus on the same works by the same artists, and have the same mission: to document the centrality of decoration—in specific commissions but also more broadly, as a founding principle—in the works of all the Impressionists, with the exception of Alfred Sisley. Although he never undertook a mural decoration, Edgar Degas confided to his dealer, Ambroise Vollard, that “it has been my lifelong dream to paint walls.” “Painting is done, is it not, to decorate walls; so it should be as rich as possible,” Pierre-Auguste Renoir explained to Albert André as he was completing his last monumental figure painting, The Bathers (1919).

Both books survey a number of decorative cycles, from Paul Cézanne’s early series The Four Seasons (1860–1861) to Claude Monet’s twenty-two glorious panels of Water Lilies (1915–1924). They redirect attention to canvases executed for specific interior spaces, as overdoors and decorative panels for dining rooms, salons, galleries, even stairwells, and occasionally as insertions into actual doors. And they reveal how deeply engaged many of the Impressionists were, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, in experimenting with new techniques in a variety of media: painting fans and ceramic tiles, pioneering the use of colored mats and frames, and even patenting colored cement as a medium for portraiture and decorative accessories. The Impressionists’ greater receptiveness in the 1890s to a more positive approach toward the qualities of decoration and the “decorative”—as expounded by Paul Gauguin and his acolytes to a younger generation of Nabis and Symbolist painters—and the implications of this for their later work are addressed insightfully in both books.1

Of the hundreds of works included in the eight Impressionist exhibitions, held intermittently between 1874 and 1886, Kisiel notes that only eight were listed specifically as “decorations.” Patry and Robbins agree: such examples constitute “a numerically marginal production.” Yet this does not prevent them from claiming that Impressionism should be considered as “a decorative movement” from the outset and that decoration, both as concept and practice, is “essential for an understanding of their art.”

This is a major revision of the historiography of Impressionism, foregrounding what had previously been considered marginal, episodic, and ephemeral activities. The Impressionists’ principal medium was oil on canvas (and occasionally panel), in which they made easel paintings in various formats. Their primary purpose was to exhibit their works regularly and to sell them: in the annual Salon, in group exhibitions, in dealers’ galleries, or at auctions (with generally disappointing results for most of the 1870s). In July 1880 Renoir refused a commission to decorate the country house of a potential patron, Philbert Joslé de Lamazière—a lawyer, music lover, and managing director of La Presse—because he did not want to be interrupted “on the picture of rowers I’ve been itching to do for a long time.” While far more expeditious in his practice than Manet, he nonetheless worked for several months on Luncheon of the Boating Party, finishing it in January 1881.

Founding members of a radical movement that remained highly contested during the 1870s and 1880s, as artists in their twenties in the early 1860s the future Impressionists had followed the example of Gustave Courbet, but in the following decade were increasingly influenced by Édouard Manet, who declined to exhibit with them. From Manet they developed a new manner of coloristic modeling, the suppression of half-tones, and the application of paint in fragmented and visible brushstrokes. (The most frequent criticism of their works was that they were unfinished.) With the exception of Degas, the Impressionists were committed to working outdoors and then completing their canvases in the studio. In their portraits, landscapes, and genre paintings—occasionally of considerable scale—they introduced “the natural light of day penetrating and influencing all things,” as Mallarmé noted.

Uncompromising in their “New Painting,” they nevertheless sought the support of collectors, critics, and dealers, and were reluctant to turn their backs on official channels of patronage and exposure. As Renoir reminded their dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, in March 1881:

There are barely fifteen art lovers in Paris capable of liking a painter who is not in the Salon. There are 80,000 who won’t even buy a nose if the painter is not in the Salon. That is why, as little as it seems, I send two portraits to the Salon every year.

Two months earlier, after a decade of struggle, Pissarro had reported joyfully to his wife that Durand-Ruel, “one of the great dealers in Paris,” had acquired a large number of his works and “has offered to take all that I produce in the future. Here is peace of mind for a while, and the opportunity to create important work.” Durand-Ruel extended the same courtesy to the other Impressionists, and after his business emerged from the financially unstable early 1880s, he remained their primary support, establishing a solid market for Degas and Monet by the 1890s.2 At that point, the “great Impressionists of the Grand Boulevard,” as Van Gogh called them, had long abandoned their group exhibitions and shared manifestos and, with the exception of Sisley, were enjoying increasing recognition, acceptance, and prosperity.

Advertisement

Kisiel’s and Patry and Robbins’s surveys both begin with early decorative projects by Cézanne and Renoir that cannot be considered Impressionist at all. Cézanne’s enormous and ungainly vertical panels The Four Seasons—three of which are inscribed “Ingres,” the fourth “1811,” in honor of Ingres’s Jupiter and Thetis at the nearby Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence—were painted around 1860–1861 directly onto the plaster walls of the Grand Salon of his family’s country house, the Jas de Bouffan. They were joined by a maladroit (and similarly overscaled) copy after Larmessin’s engraving of Nicolas Lancret’s Game of Hide and Seek (1737)—an early example of the revival of the taste for French rococo painting that was being championed at the time by the Goncourts.3 In 1865 Cézanne painted a monumental portrait of his father reading, which occupied a commanding position in the center of the room, as well as other history paintings earnestly pastiching Baroque masters, added around 1869. While still an “ouvrier en peinture,” his aspirations to make paintings for museums was evident at this early stage.

In 1868 Renoir—who as a teenager had apprenticed as a porcelain painter—was commissioned by the architect Charles Le Coeur to decorate some rooms in the hôtel particulier he was building in Paris for a Romanian aristocrat, Prince George Bibesco. Renoir submitted Tiepolesque designs for a ceiling and a project for a heroic overmantle in the prince’s Salle des Armes, inspired by Antoine Coysevox’s stucco medallion of Louis XIV on Horseback in the Salon de la Guerre at Versailles.

Decoration of the interiors of the hôtel Bibesco was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War and the ravages of the Commune. Work resumed in the summer of 1871, but Renoir was not the only decorator involved. As his younger brother Edmond reported, Bibesco’s “vast and luxurious reception rooms” were adorned by two ceilings, one by Renoir and the other by the well-established (and now forgotten) decorative painter Auguste-Alfred Rubé (1817–1899), who worked for various Parisian theaters. (Rubé’s participation in this commission had hitherto passed unnoticed.) Naturally enough, Edmond emphasized his brother’s contributions: “Be sure to remember the name Renoir: he will become a great painter if he is given major works.”

In the 1870s and early 1880s, several Impressionists were commissioned to provide decorative ensembles for the residences—primarily in the country—of some of the small group of patrons and collectors who supported them. In 1876 Renoir painted two vertical panels of fashionably dressed figures for the narrow stairwell of the editor Georges Charpentier’s Parisian townhouse. Between 1877 and 1880 Renoir’s friend and patron Paul Berard, a banker and diplomat who commissioned many family portraits, had him paint hunting trophies and floral still lifes directly onto the paneling of the dining room in his château de Wargemont outside Dieppe (still in situ today). In 1879 Berard’s neighbors in Dieppe, the celebrated psychiatric doctor Émile Blanche and his eighteen-year-old son, the aspiring painter Jacques-Émile, requested a pair of decorations on Wagnerian themes for the younger Blanche’s new studio. (They were to adorn a small balcony used to store paints, brushes, and casts after the antique.) Having been given the wrong dimensions, Renoir produced an identical second set and sold the unused canvases to a dealer.

Earlier in the decade, Pissarro had also undertaken two decorative commissions for well-to-do clients. (This would be the full extent of his employment as a “decorator.”) The magnificent series The Four Seasons (1872–1873) for the dining room of the country house in Saint-Cloud of the financier Gustave Arosa—whose father had been the Rothschilds’ Madrid agent—was executed with all the concentration and refinement of Impressionist easel paintings. The art historian Richard Brettell noted that they “can be justifiably seen as the single most important manifestation of Pissarro’s interests during the classic Pontoise period.” Pissarro received 800 francs for the four pictures in March 1873, more or less the going rate for Impressionist paintings at the time (although he had labored on them intermittently for about a year). They were likely the first of his works to come to Gauguin’s attention. Between 1871 and 1873, while training as a stockbroker, Gauguin was much in the company of the banker and his family—Arosa had been his guardian since his mother’s death in 1867—and he would have been able to follow the commission and its execution “from beginning to end.”

Advertisement

Two years later, Pissarro was asked by a distant cousin, Alfred Abraham Nunès, to provide two overdoors for the dining room of his Villa Josette in Yport on the Normandy coast. In April 1875 Nunès sent him the dimensions (almost square in format), requested that the paintings be finished as quickly as possible, “pour être agréable à ma femme,” and advised on the subjects: “It would be good if you could choose two different effects of nature, as for example, spring and autumn.” Pissarro complied in part; he depicted autumn and winter, the latter a dazzling blue and white snowscape reminiscent of Courbet. Just as he might for exhibition pictures, Pissarro made smaller preparatory compositions from nature before painting the larger overdoors in the studio. Hence his request for 2,000 francs, which Nunès dismissed out of hand. “While I do not wish to haggle over your pictures, which, as you know are entirely to my taste, I cannot and will not spend 2,000 francs on decorations for my dining room.” Pissarro had to be content with 1,200 francs.

In June 1876 Monet was commissioned to paint a series of four large decorations for the Grand Salon of Ernest and Alice Hoschedé’s opulent château de Rottembourg at Montgeron, twelve miles southeast of Paris. This eighteenth-century residence had been inherited by Alice in 1870, and she was financing its refurbishments largely through her impressive fortune. (Having separated from her husband, Alice became Monet’s companion after Camille Monet’s death in September 1879; she and Monet finally married on July 16, 1892.)

Ernest Hoschedé, the son of a textile merchant of modest origins, was the proprietor of the Parisian department store Au Gagne Petit and a passionate collector of contemporary French painting. In May 1874 he had acquired Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) from the first Impressionist exhibition. Between September and December 1876 Monet embarked on the four large canvases: a pair of garden views, a scene of hunters at a shoot, and a riotous composition of a rafter of turkeys disporting themselves on the château’s grounds. At the Third Impressionist Exhibition, which opened on April 4, 1877, Monet exhibited several paintings related to his time at Montgeron, including The Turkeys, which he listed, provocatively, as a “Décoration non terminée” (an unfinished decoration). One wag noted that this was indeed a painting “to frighten the horses.”

There is still some uncertainty as to whether Monet’s series was ever fully installed in the Hoschedés’ Grand Salon and how much he was paid for his work. From Monet’s account books, Kisiel estimates that between September and December 1876 he received just over 3,000 francs for expenses and another 2,500 francs for the completed decorations and the related preparatory compositions (a considerable amount). The opportunity for further commissions of this sort was dashed, however, when the profligate Hoschedé declared bankruptcy in August 1877. His collections and furniture at Montgeron were auctioned in Paris the following summer, and such was the lack of interest in his Impressionist pictures that Monet felt obliged to buy back two of his decorations from the series for derisory sums.

Somewhat surprisingly, the next decorative commission that Monet received, in May 1882, seems to have presented unexpected difficulties. Durand-Ruel wanted to adorn the large double doors of his dining room at 35, rue de Rome in Paris with still-life paintings. Monet was provided with canvases of the appropriate dimensions since each door was to contain six decorations in all, inserted into the paneling. He delayed starting work on a fairly straightforward, almost banal, program of still lifes of fruits and flowers until September 1883, much to his dealer’s frustration. He finally delivered some of the canvases by November, but the project took a turn for the worse in February 1884 when Durand-Ruel moved to another apartment on the first floor in the same building. Monet was now charged with decorating five double doors in the Grand Salon, but it was only in November 1884 that he received the additional canvases. It took him almost another year to complete the commission. In late October 1885, Durand-Ruel was still urging him on, reasoning that since the weather was so bad, “you must surely be less averse to finishing my panels, since you can hardly work out of doors at the moment.”

Durand-Ruel seems to have had high hopes for marketing Impressionist decorations. In July 1884 he explained to Monet, “I spent three hours with a group of capitalists, whom I am trying to convince and encourage. I took them to the rue de Rome where they reveled in your painting. It is there that I can get the best results, and I think we have already made good progress.” Durand-Ruel considered that a domestic setting—the Grand Salon rather than the gallery—had the potential to expand the Impressionists’ clientele. In February 1885 he informed Monet that he had once again brought several “serious art lovers” to the rue de Rome to see his paintings and had also been working to secure an important decorative commission for Renoir. In part, this was a way of pushing Monet: “Do try and finish the panels for my Salon. Your decoration is beginning to bear fruit and this will bring you new admirers and clients.” Nothing came of the proposed project for Renoir, and Monet continued to drag his heels on Durand-Ruel’s doors. But the encounter suggests that it was the dealer rather than the painter who was the more invested in such decorative commissions.

According to Mary Cassatt, Manet claimed that Degas, not Paul Baudry, should have been given the commission to decorate the foyer of Charles Garnier’s Opéra de Paris (inaugurated in 1875). In an article he published anonymously in L’Impressionniste on April 28, 1877, Renoir was also critical of both Baudry’s and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s contributions there and argued for a thorough reform of modern architectural practice. At first glance, the Impressionists would seem the artists least suited, in every way, to the Third Republic’s program of decorating the interiors of public buildings, yet between 1878 and 1880 both Manet and Renoir made earnest attempts to secure such monumental official commissions.4

After exhibiting the multifigured Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876) as the centerpiece of his contribution to the Third Impressionist Exhibition in April 1877, Renoir marshaled the connections he had made at Madame Charpentier’s salon to help him land a commission for the state. As he informed her husband in December 1878, he had the ear of the Paris deputy, Eugène Spuller, whose portrait he had painted the year before, and Spuller was prepared to petition on his behalf. “But he has asked me for the most precise information as to what might be possible: he wants me to tell him, ‘I want this ceiling, or that wall or staircase in such and such a building.’” In order to respond appropriately and make headway “with the needs of the budget,” Renoir asked Charpentier for an introduction to the office of the minister of fine arts, in which a friend of his was employed.

Manet’s and Renoir’s efforts came to nothing. As Kisiel notes, both artists launched their campaigns too early and did not approach the appropriate agencies. Moreover, this was a competitive, bureaucratic arena dominated by experienced history painters such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. By the 1890s, however, avant-garde critics began to ask why the Impressionists had not been selected for any of these municipal commissions. Between August and November 1892, after Jules Breton reneged on his large landscape for the first-floor gallery of the Hôtel de Ville, Monet was encouraged by Rodin and Bracquemond to present himself as a substitute candidate. He received insufficient votes from the committee—four as opposed to the ten awarded to Pierre Lagarde, a decorative painter working in the style of Puvis de Chavannes and forgotten today.

Eight years later, in December 1900, encouraged by his friend Paul Signac, Pissarro briefly considered participating in the competition to decorate the Salle des Fêtes of the town hall at Asnières, a working-class suburb northeast of Paris. Kisiel reproduces a preparatory study in gouache for a panel showing the railway bridge crossing the Seine at Asnières; Patry and Robbins note that in the end Pissarro decided against submitting any sketches for the jury’s approval.

While they were in every case unsuccessful, the ambition of some of the Impressionists to seek public commissions remains unexpected, even surprising, today. Less so is their eagerness in the late 1870s to experiment in a variety of techniques, media, and formats associated with both the decorative and industrial arts: an “unprecedented effervescence,” as Kisiel notes. With Degas and Pissarro leading the way, between 1877 and 1880 many of the Impressionists painted and exhibited fans; decorated faience, plates, planters, and Barbotine ware; painted on Haviland ceramic tile; and worked in distemper, metallic paint, and mixed media. In 1879 Degas even encouraged Caillebotte to use gold, silver, and colored powders, “which you can purchase from any of the shops that sell accessories for flowers.” Pissarro, always the most adventurous, was exchanging recipes for painting in cheese with his son Lucien in the early 1890s. After his initial experiments in mixing Gruyère with quicklime had failed, he recommended having a pharmacist handle the preparations: “It’s just like pastel.”

One of the most ambitious of such projects was to introduce McLean cement—a British invention used to make chimneypieces imitating colored marble for export to the colonies—to the French and Belgian markets. In April 1877 Caillebotte advanced 30,000 francs to Renoir and Alphonse Legrand (an employee of Durand-Ruel’s) to form a company to develop products in this medium. In the patent registered by Renoir in July 1877, it was specified that this was for “decorative painting in white and colored cement to be used in panels, door jambs, friezes and ceilings.” Only a handful of lackluster objects in McLean cement survive today, among them Renoir’s mirror frame for Madame Charpentier and his little portrait of Georges Rivière (the artist’s closest friend and most fervent advocate at the time). The enterprise was a complete failure, and Caillebotte dissolved it a year later in April 1878, “because of the total loss of capital.”5

Taken together, these various artisanal, protoindustrial activities—in which neither Cézanne nor Monet participated—throw light on the Impressionists’ engagement with the experimental, as well as their willingness to consider new markets and to work in different media. What it does not suggest, however, pace Kisiel, is a desire on the part of Renoir, Degas, or Pissarro “to abandon painting and therefore the fine arts stricto sensu to experiment in other techniques.” By the same token, decorating and exhibiting fans does not indicate any ambition—or any capacity—to paint lunettes and tympana in public buildings, since these delicate items can hardly be said “to evoke the domain of grand decoration.” Similarly, the distinctive double-square format of Degas’s scenes of ballerinas rehearsing and jockeys preparing for the race—his “tableaux en longueur”—cannot be related to overdoors or decorative friezes, as both books claim. It strains the evidence to suggest, for example, that his Dancers in the Classroom (circa 1880) was painted to serve a decorative function. This carefully elaborated, freestanding cabinet picture was acquired around 1880 by Jacques Drake del Castillo, a wealthy winegrower from Touraine, to add to the small collection of Impressionist paintings in his Parisian hôtel particulier. There is no reason to believe that it was ever installed as an overdoor there.

Both books are on much firmer ground in their analyses of the small but significant number of Impressionist paintings that were conceived of and exhibited as “decorations.” Monet’s large, glorious Luncheon, painted in 1873 but held back until the Second Impressionist Exhibition of April 1876, shows the aftermath of an elegant luncheon at his villa in Argenteuil (see illustration at beginning of article). In a garden full of flowers, sunlight dapples the white tablecloth on which are visible the remnants of coffee and dessert. An early reference to the picture described it more accurately as “after the luncheon.” Relegated to the background at the upper right are the hostess, Monet’s companion, Camille Doncieux, in a white summer dress, and her parasol-bearing guest. Also easy to overlook is the little boy in a straw hat—the six-year-old Jean Monet—seated in the foreground at left, playing with his toy. The dynamic angle of the circular table and the garden bench propels the bedazzled, even disoriented, viewer into this sundrenched scene. With its deep purple shadows, syncopated dabs of color, and figures relegated to the margins, The Luncheon discourages narrative or anecdotal interpretation. In the catalog of the Second Impressionist Exhibition, Monet listed the work as “un panneau décoratif” (a decorative panel). This too was provocative, since the term panneau, rather than tableau, carried associations of the artisanal and the workshop.

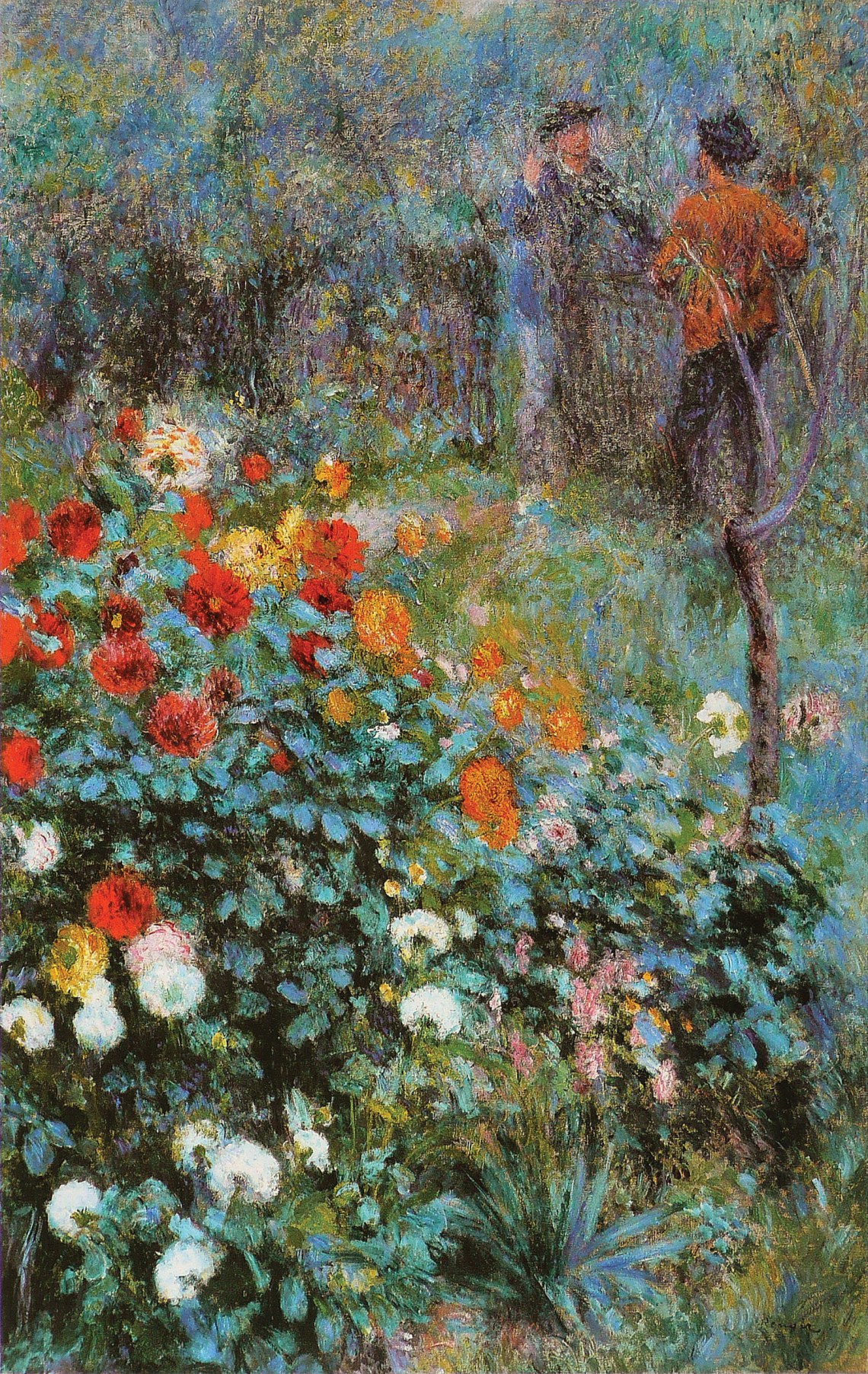

The same “all-over” quality is seen in Renoir’s Garden in the Rue Cortot, Montmartre (1876), exhibited as The Dahlias at the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877 and referred to by Rivière as a “splendid decoration” (see illustration below). As with Monet’s Luncheon, it was a decoration in search of a location. Once again the structure and scale of Renoir’s unorthodox large vertical garden scene—landscapes are generally horizontal in format—challenge the viewer. Our eyes are drawn to the verdant clump of flowers that dominate the picture, and only gradually do we become aware of the young men in casual conversation in the background at upper right—figures similar in appearance to Renoir and Monet themselves.

Painted a decade later, in a style that consciously rejected the fragmentary brushwork of Impressionism—but not its radiance—Renoir’s The Great Bathers (1884–1887) is discussed at length in both books. Elaborated over three years through many preparatory drawings, it was exhibited at Georges Petit’s Sixth International Exhibition in May 1887, at Renoir’s insistence, as An Experiment in Decorative Painting (Essai de peinture décorative). A rumination on Raphael’s frescoes in the Villa Farnesina, which Renoir had seen six years earlier in Rome, its friezelike composition inspired by François Girardon’s bas-relief Bath of the Nymphs (1668–1670) at Versailles, The Great Bathers was Renoir’s magisterial effort to imbue Impressionism’s coloristic modeling and heightened luminosity with greater rigor and structure, primarily through drawing. A polarizing work among his Impressionist colleagues—Monet admired it, Pissarro did not—The Great Bathers remained unsold after Petit’s exhibition and was only acquired by Jacques-Émile Blanche in 1889 for the modest sum of 1,000 francs.

Late in life, Renoir spoke of having undergone a “crisis of Impressionism” at this time; creating The Great Bathers was one way out of this impasse. Between 1882 and 1884 he was also reconsidering the theoretical underpinnings of his art and produced a series of draft essays on the concept of Irregularism, which took Nature’s irregularity as a guiding principle.6 Renoir’s Société des Irrégularistes advocated for a more holistic system that included practitioners of the decorative arts—tapestry and porcelain designers, ornamentalists, muralists—in addition to painters and sculptors. Nothing came of the movement, and Renoir’s drafts—including a lengthy Grammaire des Arts—remained unpublished. As Robert Herbert and other art historians have noted, it was in these years that the renamed Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs was campaigning for a renewal in the training of the nation’s artisans and craftsmen in the luxury trades, one that married utility with beauty.

Yet despite Renoir’s earnest commitment to a revitalization of all the arts—and his horror of industrialization and progress in general—it is hard to see how these ideas are inflected in The Great Bathers, which remains essentially a large-format exhibition picture and a harbinger of the rappel à l’ordre of his later years. Renoir’s elusive descriptive title, Essai de peinture décorative, still remains to be satisfactorily interpreted, and so it is hard to agree with Patry and Robbins’s assertion that The Great Bathers is “a powerful decorative manifesto.” A manifesto of what, precisely?

Instructive here is Degas’s contrarian response to the news that Cassatt had been invited to provide a mural for the Woman’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. “I wish you could have heard the conversation I had with Degas on what is known as ‘decoration,’” Pissarro wrote to his son, Lucien, in October 1892.

I am wholly of his opinion: for him it is an ornament that should be made with a view to its place in an ensemble, and it requires the collaboration of architect and painter. The decorative picture is an absurdity, a picture complete in itself is not a decoration.

It is hard to discount Degas’s and Pissarro’s assessment. Decoration and the decorative were not the Impressionists’ primary objectives or the driving force of their art in the decades during which the movement flourished. But with Gauguin and the Nabis exalting the intrinsic qualities of the decorative—anticipating Matisse’s maxim that “for a work of art, the decorative is an extremely precious thing: it is an essential quality”—it is the case that from the 1890s Monet’s serial paintings and Renoir’s nudes evolved in ways that came to embody some of the values associated with decoration and “l’art décoratif.”

The greatest decoration made by any Impressionist is Monet’s Nymphéas (Water Lilies) for the Orangerie in Paris (see illustration below). In Le Décor impressionniste, Patry and Simon Kelly provide excellent overviews of a project that preoccupied him for the last thirty years of his life. An enthusiast of the hybrid water lilies cultivated by the horticulturalist Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac, whose yellow, pink, and deep red flowers had been a sensation at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 (until then only white waterlilies were known), Monet had begun to purchase plants from him for his garden at Giverny as early as 1895.

In the summer of 1897 he apparently contemplated decorating a circular room with water lilies, painted “with all the delicacy of a dream.” He returned to this project in 1909 with forty-eight paintings of water lilies, which he called “a series of aquatic landscapes,” that were shown to acclaim at Durand-Ruel’s gallery. Monet was now thinking of a moderately sized circular dining room, empty except for a table in the center, with a frieze of water lilies painted from the ground up.

Having been diagnosed with cataracts on his right eye in July 1912—and reluctant to undergo surgery—Monet began working on large horizontal canvases of water lilies in the spring of 1914, informing Durand-Ruel in June of that year that he was getting up at four in the morning and painting all day, his eyes no longer troubling him. Water lilies would be the principal subject of Monet’s late years. In addition to his panels for the Orangerie, he produced some 240 canvases, forty of which were monumental in format.

Only in January 1915, five months after Germany declared war on France, did Monet embark upon his Grandes Décorations for an as-yet-unspecified location. In June he estimated that the cycle of twenty large panels would take him five years to complete and require 170 square meters of canvas. The Nabis painters Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard lunched with Monet at Giverny on June 21, 1915, and marveled at what had already been accomplished. “After luncheon, alone with Bonnard in the little studio,” Vuillard noted in his diary. “[Monet’s] large canvases are like the Sistine Chapel; idea, rhythm and color; there is great lyricism in all of his work.”7 The next month, Monet received planning permission to build a large studio at Giverny—the third on his property—and beginning in October 1915 he worked on his panels there. In November 1918, at the time of the Armistice, he donated to the state the first two Water Lilies “as a bouquet of flowers in celebration of victory in the war.”

There was still no decision as to where exactly the water lily decorations would reside. By the summer of 1920 Monet seems to have settled on a cycle comprising twelve monumental panels, having refused the extraordinary offer of $3 million for the series from a delegation of the Art Institute of Chicago. In collaboration with his good friend Georges Clemenceau, the politician and former government official responsible for the commission, Monet finally settled on a location. A pavilion was to be built next to the new Musée Rodin, housed in the former hôtel Biron on the rue de Varenne and recently inaugurated in accordance with Rodin’s wishes. In December 1920 Monet reviewed plans for the large circular gallery in which his twelve panels would be mounted, with a frieze of wisteria decorating the upper section of the walls.

Monet became disenchanted with the scale of the room, which he dismissed as a “veritable circus ring,” and insisted that his paintings be shown in a sequence of two elliptical galleries (which could not be accommodated on the proposed site). Clemenceau was responsible for finding a solution to this impasse in April 1921, when he identified the dilapidated Orangerie on the Place de la Concorde, built in 1852 to house Napoleon III’s orange trees, as the home for Water Lilies. Monet inspected the site on April 6, 1921, and gave his approval. Finally working with the chief architect of the Louvre, who supervised renovations at the Orangerie and designed the two requisite galleries, on April 12, 1922, Monet signed an official act of donation for nineteen panels and promised to complete them by April 1924.

In these latter years Monet was once again plagued by cataracts and the fear of impending blindness. He underwent three eye operations between the summer of 1922 and the summer of 1923, and with the help of corrective lenses from Germany was able to return to his decorations in October 1923. With the improvement of his vision, he informed the painter André Barbier in October 1925, “I am working as never before, satisfied with what I am doing and if the new eye glasses are still better, I ask only that I live to be 100 years old.” In the end, and despite the official agreements, Monet did not relinquish any of the decorations during his lifetime. Nor did he live to see them installed. He died at Giverny, aged eighty-six, on December 5, 1926; the Orangerie, with its twenty-two monumental water lily decorations in two galleries, opened to the public five months later, on May 17, 1927.

It is something of a shock to learn that for much of its early history the Water Lilies cycle—a renowned pilgrimage site today, less trafficked than the Sistine Chapel but inspiring a similar sense of awe among many of its visitors—was ignored (or disdained) by the public. Both Cassatt and Blanche dismissed the decorations as “glorified wallpaper,” and as late as December 1952 the Surrealist André Masson lamented that Monet’s series was overlooked in “this deserted place in the heart of Paris.” As the art historian Romy Golan has noted, Monet’s cycle was installed in what was initially seen as “a splendid cul-de-sac,” and his heirs had to remain vigilant in monitoring the galleries. In 1935 an exhibition of Flemish tapestries was mounted on movable partitions in them, and Michel Monet intervened with the administration the following year to ensure that this would not happen again with the exhibition “Rubens et son temps,” which attracted over a million visitors. (It is not clear that he succeeded.)

Restorations of 2000–2006 removed the floors built above Monet’s galleries in the 1960s to house the Walter- Guillaume donation, a collection of 148 outstanding works given by Domenica Walter (widow of both collectors). These were now replaced with large skylights, and a translucent velarium was installed across the two elliptical galleries at the same height as the original ceiling. Once again it is possible to contemplate Monet’s Water Lilies in natural light, as one could in 1927. In immersing the viewer in the fleeting and evanescent effects of clouds, sunlight, and air as they pass overhead and are reflected in the water, Monet undertakes a consummate and magnificent example of Conceptual—as well as Impressionist—art, each room transporting us to a nonexistent spot mid-pond, a tiny island of the mind.

-

1

Vanguard critics in the 1890s were more critical of the limitations of naturalism and the priority given to easel paintings, both now seen as characteristic of Impressionism in its heyday. See Nicholas Watkins, “The Genesis of a Decorative Aesthetic,” in Gloria Groom, Beyond the Easel: Decorative Painting by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890–1930 (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press, 2001). ↩

-

2

On Durand-Ruel and the Impressionists, see my “How He Ruled Art,” The New York Review, December 3, 2015. ↩

-

3

On the influence of eighteenth-century French Rococo painting on the Impressionists, which focuses primarily on Renoir, see Renoir: Rococo Revival, edited by Alexander Eiling (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022). ↩

-

4

Throughout his life Manet “harbored the desire to paint a large modern decorative work,” noted his friend Antonin Proust. For more on Manet’s efforts, see my “Suffering, Unfaltering Manet,” The New York Review, December 3, 2020. ↩

-

5

The ever decent and generous Caillebotte made provision in his will that Renoir would not be expected to repay any of the funds advanced for this enterprise. See Kisiel, La Peinture impressionniste, pp. 119–120. ↩

-

6

These writings, and others, were published by Robert Herbert in Nature’s Workshop: Renoir’s Writings on the Decorative Arts (Yale University Press, 2000); reviewed in these pages by John Golding, November 16, 2000. ↩

-

7

“Déjeuner chez Monet. Ses grandes toiles le Plafond de la Sixtine. Idée, rythme et couleur: grand lyrisme de toutes ses œuvres.” From the Journal d’Édouard Vuillard, Monday, June 21, 1915 (Paris: Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Ms 5397 (8), folio 27 verso); partially transcribed and translated in Charles Stuckey, Claude Monet, 1840–1926 (Thames and Hudson, 1995), p. 246. On the first page of this diary, which he began on March 14, 1915, Vuillard had written, “A quelle page sera la fin de la guerre!” ↩