“Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi,” mused Thomas De Quincey in his 1821 Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. He wasn’t worried about the real Piranesi, long dead by then; he was considering the plight of an etched figure he understood to be Piranesi in one of the artist’s Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons). “Creeping along the sides of the walls,” De Quincey wrote,

you perceived a staircase; and upon this, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself…. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived…. And so on, until the unfinished stairs and the hopeless Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall.

De Quincey never claimed to have seen the etching in question—he was riffing on hearsay from Coleridge—so our compassion is being called into play for an imaginary figure in an imaginary prison in an imaginary etching. And throughout the two centuries that followed, Giovanni Battista Piranesi the person and Piranesi the tormented trope have shared space in the world like a badly executed hologram: never invisible, never quite clear.

The actual Piranesi was born in the Veneto in 1720 and went to Rome at the age of nineteen with the dream of becoming an architect. When he took up printmaking, it was to make ends meet, and his elaborate title pages announced the authorship of “Giambattista Piranesi, Venetian Architect,” but he died with just one significant architectural project to his name. His prints, in the meantime, made him famous. Preceding the dark vaults and pointless bridges of the Carceri were the first of the Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome, 1745–1778) that were sold in volume to travelers on the Grand Tour and defined the popular image of Rome for generations: the theatrical slanting light, the grandiosity, the squalor.

But just as the architectural establishment, bewildered by Piranesi’s effervescent schemes, treated him as a crank (the architect Luigi Vanvitelli called him a “lunatic”), print connoisseurs, put off in part by his entrepreneurial success, dismissed him as a hack.

The definitive twenty-one-volume roster of important print artists, Adam Bartsch’s Le Peintre-Graveur (1803–1821), ignored him. The American Joseph Pennell, a leading light of the nineteenth-century etching revival, acknowledged his existence only to observe, “His perspective is as poor as his industry is great.” In Prints and Visual Communication (1953), one of the twentieth century’s most influential texts on printed images, William Ivins (the founding curator of the Metropolitan Museum’s Department of Prints) described him as “a commercial manufacturer of architectural prints—conveyors of information—[who] rarely let his genius interfere with his business.”

Look around, though, and somehow poor Piranesi is still everywhere. His prints pop up like background chatter in photographs, fictions, and Logan Roy’s living room in Succession’s fourth season. Jorge Luis Borges and Le Corbusier were aesthetic and philosophical adversaries, but both decorated their rooms with Vedute (the overgrown Remains of the Temple of the God Canopus for Borges, the cubic block of the View of the Villa Albani for Corbu). Louis Kahn, champion of modernist monumentality, had Piranesi’s quixotic plan of the Campo Marzio in his Philadelphia office; Peter Eisenman, architecture’s field marshal of fragmentation, has the same print in his bedroom.

Sergei Eisenstein, Sir Walter Scott, and my late in-laws had little in common but for the chosen companionship of Piranesi. When Eisenstein wrote, “I am now looking at this etching on my wall,” it was 1946, and he was in his Moscow apartment with eyes on Carcere oscura (Dark Prison). Scott never wrote about the Vedute that hung in his Edinburgh dining room (unlike Eisenstein, he had not bartered with a provincial Russian museum to secure them, having taken the easier route of inheriting from an uncle), but the prints’ dramatic entanglements of heroic history, ruination, and busy human actors surely reverberated with the author of Ivanhoe. Exactly how an impression of Piranesi’s view of the pronaos of the Temple of Concordia—majestic columns above, drunken wastrels below—found its way to the walls of my in-laws’ summer cottage is a mystery, but they were academics who gave great thought to the competing claims of historic preservation and living cities, so it felt at home and has remained.

When Piranesi’s three-hundredth birthday rolled around on October 4, 2020, the world had other things on its mind, but the celebratory exhibitions and publications have now begun pouring out. Taschen has reissued Luigi Ficacci’s catalogue raisonné of the etchings (originally published in 2000)—this time with 1,028 plates in a single “XL” volume (T-shirt sizes having replaced the old language of quartos and elephants). Piranesi and the Modern Age by the architectural historian Victor Plahte Tschudi was published this past fall in conjunction with an exhibition at the National Museum of Norway.1 And at the Morgan Library, the curator John Marciari has assembled “Sublime Ideas: Drawings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi,” supplementing the museum’s celebrated cache of Piranesi drawings with important loans. These efforts do much to explain his remarkable staying power and the current relevance of even his loopiest creations.

Advertisement

Piranesi’s prints made him “the great apostle of Rome,” Marciari writes, “a connoisseur of the Eternal City’s ever-adaptive, ever-eclectic art,” but as a Venetian he played to the clichés of both cities. The latter gave him a taste for illusion, confusion, and elaboration; the former, an allegiance to the here and now of the past. In drawings at the Morgan, the young architect tests out the physics-defying Venetian Rococo of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo with designs for wall panels that sparkle with asymmetries and arabesques. A frothy pen-and-ink image summons up a ceremonial gondola on which satyrs, a winged dragon, crowns, and medallions dissolve in a flurry of wavelets.

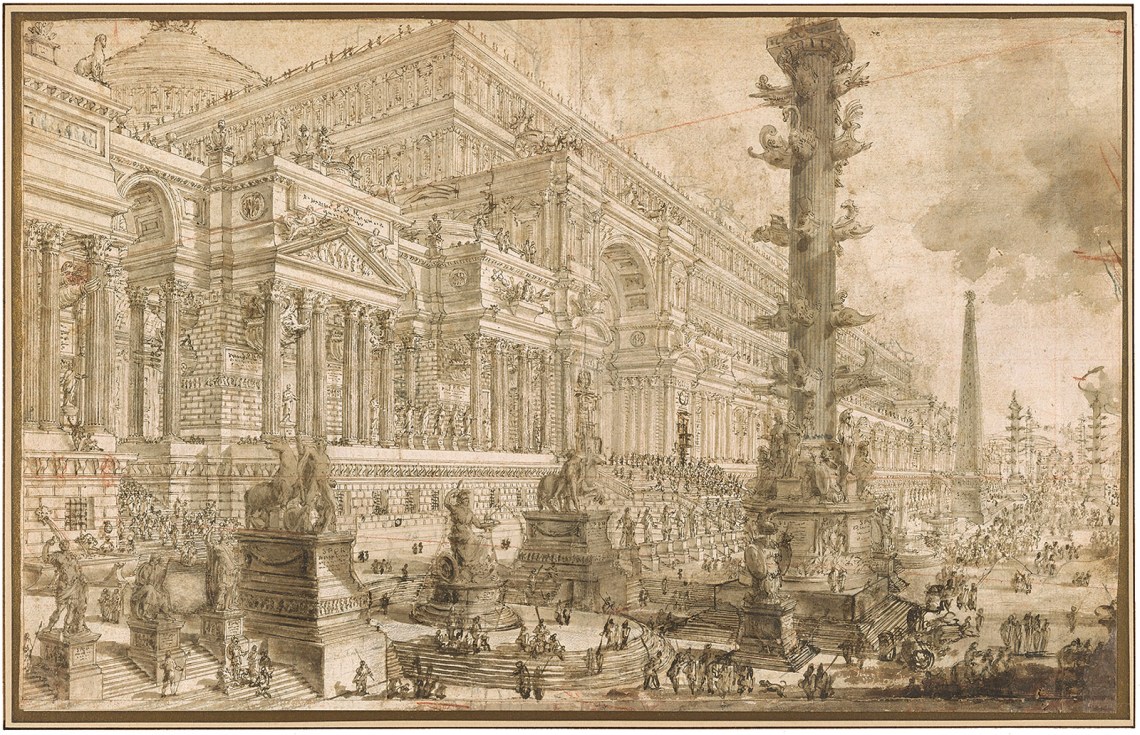

His early architectural inventions employed more right angles but were no less spectacular or far-fetched. In Architectural Fantasy with a Colossal Façade (circa 1743–1745), Corinthian columns and Palladian pediments gang up in aid of what Marciari aptly calls “a grandeur bordering on the megalomaniacal.” The façade is make-believe, but the plaza in front is stocked with real Roman monuments—the Quirinal Horse Tamers, a seated Seneca, the standing Domitian from the Palazzo Giustiniani. This was the conceptual territory Piranesi made his own: a tidal flat where what has been left behind gets flooded by visions of what might be. Examining Piranesi’s excited dreams of ancient Rome 170 years later, the young Le Corbusier was appalled: “Porticos, colonnades, and obelisks!!! It is crazy. It is horrible, ugly, and idiotic.” Horace Walpole was more of a fan, enthusing about “scenes that would startle geometry, and exhaust the Indies to realize.”

Piranesi’s first substantive etching project, the Prima parte di architetture, e prospettive (First Part of Architecture and Perspectives, 1743), includes some lightweight etchings of romantic ruins—all-purpose toppled columns and invasive greenery that would not be out of place on a length of toile de Jouy—but most of the prints follow the lead of the Colossal Façade, imagining a spotless, gargantuan, urbane antiquity. While the dedication page bemoans the dearth of visionary patrons who might enable architects like himself to express themselves in stone rather than on paper, the tenor of the images is that of eager invention. It is difficult to imagine what purpose could be served by these vast arcades, but they must have been fun to draw.

The Vedute, which he began in the 1740s and added to throughout his life, cleave closer to reality, but here also he found room for play—stretching the scale, collapsing distances, and infusing everything with haphazard life. People clamber over broken walls, herd sheep, gesture at each other in Italian; women hang clothes on a laundry line tethered to the Temple of Cybele (now known as the Temple of Hercules Victor). These actors are too peculiar and specific to qualify as staffage (the art-historical term for the generic persons dotted about painted landscapes), and sheets of figure studies at the Morgan show Piranesi clocking the attitudes of workers in his printshop and people on the street.

In one etching of the Pantheon’s interior, the angled beam of light from the oculus is echoed by a leaning, forgotten ladder in the shadowed portico. In his expansive vista of St. Peter’s Square, the imposing symmetry is disrupted by the arrival of a florid carriage that, as a wall label at the Morgan points out, has nicked its ornamentation of bird wings, medallions, and curlicues from Piranesi’s earlier ceremonial gondola.

Taking us through Piranesi’s career on the not-quite-parallel track of his drawings, the Morgan illuminates his inventiveness and also his pragmatism. Few of the surviving drawings match finished prints, perhaps because he preferred to reinvent things afresh on the plate, or perhaps because once a drawing was replicated in print, there was no need to preserve it. The drawings that he kept seem to be those that still had something to give, and they served as an ongoing library of forms and ideas.

In the Carceri Piranesi abandoned the disciplined, schoolboy line he used in the Prima parte in favor of something more spontaneous and frisky. Masonry is conjured with feathery strokes and Edward Koren–esque wiggles. He seems to be making it up as he goes along—Harold with a purple etching needle, laying out parkour courses of towers, arches, ladders, and bridges. Tolkien’s account of the Mines of Moria might have been written while looking at the Carceri Gothic Arch:

Glimpses of stairs and arches, and of other passages and tunnels, sloping up, or running steeply down, or opening blankly dark on either side. It was bewildering beyond hope of remembering.

Drawings show earlier investigations of similarly incomprehensible spaces: the passageways in Perspective of Massive Piers and Arcades (circa 1742–1743) swell and contract in a queasily organic way, while darkened vaults executed in ink-and-wash on blue paper are disconcertingly cinematic. In the Carceri etchings, vaults and piers repeat without purpose, and ropes fall like large block-and-tackle pulleys in aimless catenary arches. None of them are particularly believable as places of incarceration—even the torture in The Man in the Rack happens in a picturesque ruin adorned with bas-reliefs and open to the sky. Piranesi’s audience, however, would have understood the subject as a pictorial trope rather than an institution. Prisons were “standard fare,” Marciari points out, “for architectural draftsmen and theatrical designers,” and stage design had been part of Piranesi’s training.

Advertisement

Returning to the series a decade after he first published them, he added two new plates and reworked the old ones for darker, more muscular drama. Shadows were strengthened and huge spikes grace beams and bollards, as if to fend off gargantuan pigeons. De Quincey’s account of “wheels, cables, catapults, &c., expressive of enormous power” wasn’t quite true, but it captured the mood and helped establish the images as metonyms for the irrational mind. Their special architectural-psychological trick was to appear simultaneously claustrophobic and infinite. More than a century after De Quincey, Aldous Huxley saw their “colossal pointlessness,” which “goes on indefinitely, and is co-extensive with the universe” as revealing the “subterranean workings of a tormented soul.” Later, nihilist aesthetes of my own generation meditated on posters of the Carceri through fugs of dorm-room pot smoke. Susanna Clarke’s recent novel of elliptical captivity and captivation is titled simply Piranesi.2 “All considered,” Tschudi writes in Piranesi and the Modern Age, “the mind itself as an infinitely extending entrapment is perhaps Piranesi’s most lasting legacy as an architect.”

For all their fame, however, the Carceri and the Vedute between them account for less than 15 percent of Piranesi’s prodigious output. Flipping through the Taschen book you encounter oceans of archaeological illustrations, designs for housewares, studies of capitals and molding profiles.

The charisma of intaglio prints is always compromised in reproduction, where they are stripped of their brawny blacks and shimmering whites and often reduced in scale. The compression of Piranesi’s nine-foot-tall columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius to ten inches eliminates everything that makes the actual prints—each assembled from six large sheets and engineered as colossal book fold-outs—such wonders. What you get in exchange for these losses, however, is a volume that is not only affordable but also conveys Piranesi’s deployment of art as argument in a way wall display does not.

The practice of framing works on paper under glass developed during Piranesi’s lifetime, and most of his plates were conceived on the older model of albums or portfolios with title pages, dedications, and texts. Those appendages could be lengthy: Divers Manners of Ornamenting Chimneys and All Other Parts of Houses (1769) came with a trilingual, thirty-five-page “Apologetical Essay in Defence of the Egyptian and Tuscan Architecture.”

The four-volume Antichità romane (Antiquities of Rome, 1756) contains more than two hundred plates illustrating paving systems and bridge abutments, floor plans and maps, pottery shards and carved reliefs arranged on shelves, a soldier guarding cannonballs behind the Mausoleum of Hadrian, also known as the Castel Sant’Angelo. Piranesi takes care to demonstrate how much is missing: surviving fragments of the great plan of Rome engraved on marble plaques float on the page like icebergs calved from a glacier, dwindling spots of firm knowledge in a sea of forgotten connections. Isolated details from family tombs show grids of small, engraved rectangles like doorbell plates to the great beyond, but the stone is shattered and the names lost.

In other places, however, he fills in the blanks with gusto. The fantastically cluttered Ancient Circus of Mars with Neighboring Monuments has near relations in Oz and Wakanda. Antichità romane established Piranesi’s reputation as a serious archaeological scholar, but no sharp line separates the didactic from the picturesque, or what he has seen from what he has imagined. The latter grows from the former like lichen on a senescent tree.

The prints of his Campo Marzio (1762) are half archaeology, half speculative fiction. One depicts the prehistoric site along the Tiber in the form of a topographic map, torn, curled and held in place with trompe l’oeil nails—an imaginary artifact from the developer’s pitch to Romulus and Remus. Another reinvents the Severan marble plan, engraved like the original to show structural walls, columns, and staircases throughout the city, but Piranesi once again interlaces recorded structures with pure inventions.

In 1764 Piranesi finally achieved the validation he longed for when he was awarded the commission to rebuild the Knights of Malta church of Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine Hill. The sympathetic Pope Clement XIII, a fellow Venetian, honored him with a knighthood, and Piranesi thereafter signed his plates “Cav[aliere] Piranesi,” but as far as his career in architecture went, it was the capstone rather than a stepping stone.

Piranesi’s last decades were largely given over to activities as a collector, dealer, and restorer of Roman antiquities. The palazzo that housed his family and workshop now became his “Museo,” described by another architect as “so full of marbles, and antiquities, that it would not stun me to hear that one day it had fallen.” The Piranesi Vase at the British Museum and the Warwick Vase now in Glasgow are the most celebrated examples of these efforts, and Piranesi’s pride is evident in his etched portraits of them. (There is also a fine drawing of the Warwick vase at the Morgan.) Unearthed at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli in shattered or incomplete condition, both were rebuilt by Piranesi, who used his knowledge of Roman decorative arts to create new materials to fill in the lacunae. As in his prints, surviving bits of ancient Rome were made whole through a combination of scholarship and invention. Though both vases were purchased as Roman antiquities, the British Museum now names the “producer” of its vase as Piranesi, and the Warwick Vase should, Marciari writes, be “celebrated as a representative masterpiece of Piranesian Neoclassicism rather than as an ancient artifact.”

This penchant for dressing younger lamb as mutton earned Piranesi the derisive sobriquet “Cavalier Pasticci” (Sir Pastiche), but most connoisseurs of the time concurred that the job of restoration was to fix what was broken and replace what was lost. Some years later the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen restored the pediment sculptures of the Temple of Aphaia and invented whole figures on the basis of a surviving foot or knee. The seam between new and old was finessed not to deceive but to enable aesthetic experience, even if at a loss of forensic clarity. The fact that guesswork was involved was a reason to put a good guesser in charge.

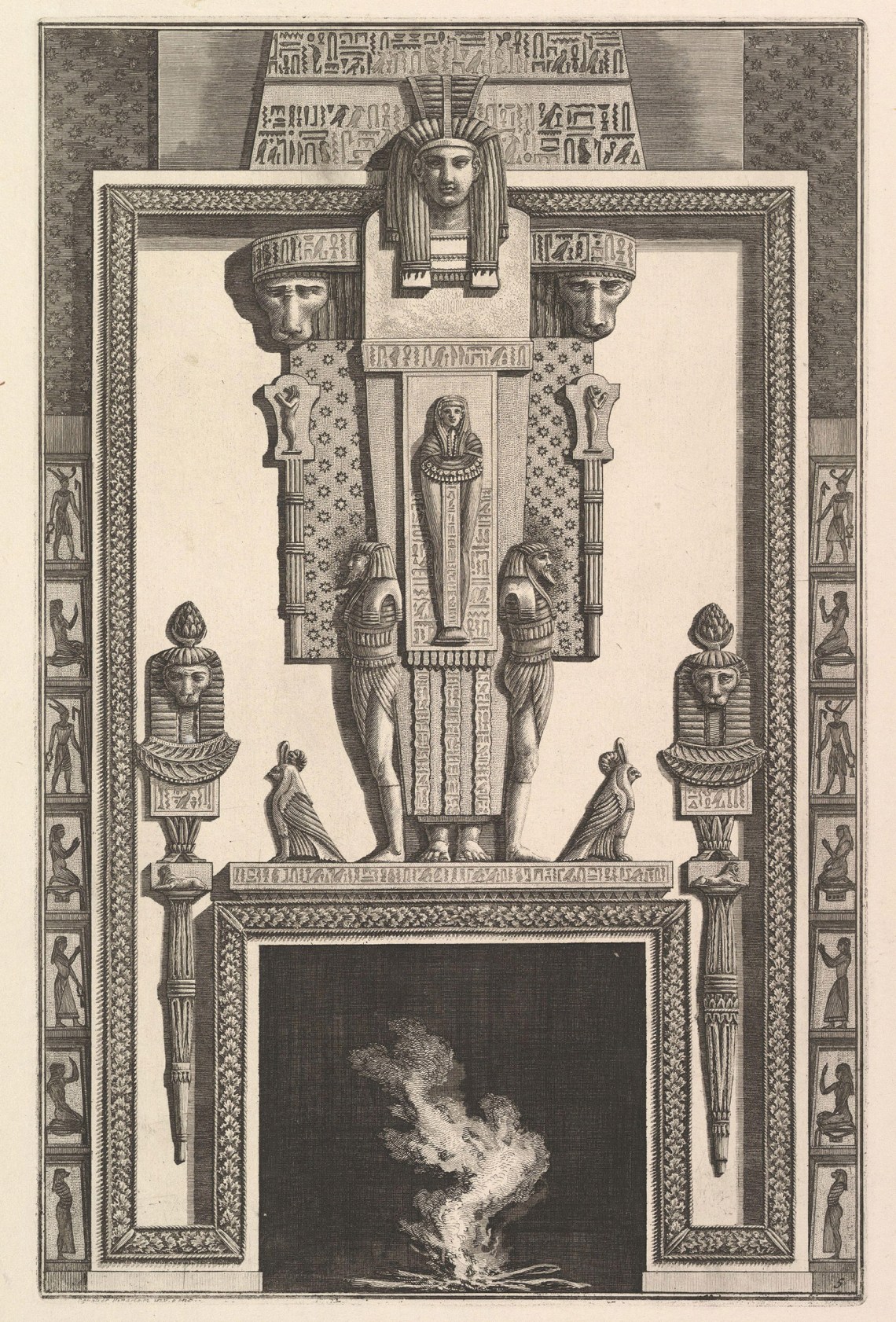

But Piranesi also believed that the past was, by rights, the feeding ground of the present. The “apologetical essay” attached to Divers Manners states its author’s ambition “to shew what use an able architect may make of the ancient monuments by properly adapting them to our own manners and customs.” The designs that follow include dozens of chimneypieces—an object-type with no ancient precedent—in styles ranging from discreetly neoclassical to carnival-sideshow Egyptian, along with candelabra, carriages, and clocks. A few of these designs were executed by artisans at the time, and in 2010 the Fondazione Giorgio Cini joined forces with the Madrid-based fabrication firm Factum Arte to transform other etchings into cast marble and bronze, but most have remained paper dreams.

The purpose of the Divers Manners was in any case as much theoretical as practical. It was a declaration of possibility and a manifesto in the tug-of-war between those who looked to the cosmopolitan classicism of Rome for aesthetic guidance and those who idolized the putative purity of classical Greece. The latter position had been argued persuasively—if not, as it turns out, accurately—by Johann Joachim Winckelmann. “All beauty is heightened by unity and simplicity,” he held, and artists such as Antonio Canova and John Flaxman responded with sublime elegance. Piranesi, meanwhile, was all in for Team Rome, precisely because of its willingness to appropriate and adapt. When he died, in 1778, Greek neoclassicism had won the day, though not, in the end, the battle.

In Piranesi and the Modern Age, Tschudi chases Piranesi’s long tail into the present, mapping his influence on “ideas ranging from existential anxiety to social liberation.” After giving the Carceri their due as avatars of nineteenth-century Romantic moodiness, he turns to the prints’ curious star turn at the Museum of Modern Art. The 1936 exhibition “Cubism and Abstract Art” introduced American audiences to the dramatic breakthroughs of Picasso, Mondrian, Malevich, and others. This might seem strange company for the Carceri drawbridge in its woolly second state (revision of the plate) from 1761, but paired with Robert Delaunay’s drawings of exploded teetering buildings, the drawbridge shed its Sturm und Drang to stand revealed as an adventure in spatial restructuring and dissolution—architecture en route to abstraction. A few months later the museum’s “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” exhibition, which explored the antirational trend in modernism, also included a Carceri drawbridge. This time, however, it was the lucid first state from 1749–1750, all loose line in open air, a fitting consort for Giacometti’s The Palace at 4 AM (1933), which stood beside it—same design, different jacket, new meaning.

In Tschudi’s telling, Piranesi presented twentieth-century creators with two gifts—one straightforward (the dynamism of high contrast and strong diagonals) and one elliptical (the idea that what’s important may be parked in the gaps between things as much as in the things themselves). Eisenstein’s films exploited both, massing dark forms in the foregrounds as Piranesi so often did and, more innovatively, recognizing the seeds of filmic montage in his motley groupings. Similarly, for architects in the later twentieth century, Tschudi argues, it was Piranesi’s inconsistency that inspired.

In the 1930s Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock summarized the idealized International Style as “unified and inclusive, not fragmentary and contradictory.” Later, when a younger generation began to question those precepts, Piranesi reemerged as a beacon of heterogeneity. “Piranesi speaks to the present in a profound and mysterious way,” Daniel Libeskind wrote in 1982.

It wasn’t the look of Piranesi’s creations that mattered—no one rushed out to build his buildings or manufacture his clocks—it was the license to accommodate the old and damaged within the living and functional. The crucial reference now was not the Carceri but the Campo Marzio, its big trompe l’oeil marble map standing, Rem Koolhaas told Tschudi, as

an emblem of the urban condition in its duality of being both planned and unplanned…chaotic and organized at the same time, or, rather, that it is an assembly of organized pieces in a chaotic whole.

A principle can look silly when applied to a clock yet feel humane and important when expanded to a city.

As in De Quincey’s imagination, Piranesi keeps appearing and reappearing, each time on a different landing, but contra De Quincey, he never seems “hopeless.” On the contrary, in the Taschen book, at the Morgan, in the myriad works whose influence Tschudi traces, he seems always in a fever of observation and creation. “I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it,” he once proclaimed.

The Vedute, the Carceri, and the Campo Marzio have each enjoyed their moment of cultural relevance and reinterpretation, but if I were to pick a Piranesi project for the present, it would be the Divers Manners. Those gewgaw-packed pages, it is true, lack the visual drama of his other works. John Updike described them as “utilitarian,” and he wasn’t wrong: they are a means to an end, careful descriptions of ideas rather than ideas in themselves. But they manifest Piranesi’s unrepentant glee in invention and his awareness that all invention is predicated on the work of others; more than any of his other publications, they challenge the limits and prejudices of our own aesthetic rulebook.

His chimneypieces are everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink agglomerations: half-clothed women with wings stand on horned bovine skulls, snakes turn into dog leashes, sphinxes stretch out on mantles above random hieroglyphs. Much of this is ridiculous and some of it hideous, but there is intermittent beauty. Inside black fireboxes, small bundles of sticks erupt into smoke and flame built from wiggly black line and white paper, each plume as solid and erratic as elkhorn corals or Chinese scholars’ rocks.

Meanwhile, the extended essay in Divers Manners reads as a defense of multiculturalism avant la lettre: Rome was “the mother of good taste, and perfect design” because all roads had led there. The inventions of Egyptians, Etruscans, and other peoples further afield had, he argues, as much claim to greatness as those of the Greeks, and anyway, “the Greecks [sic], who boast of being the inventors of almost every thing,” had pilfered their best ideas from others. He knows that isolated fragments from an unfamiliar culture cannot reveal the material or cultural logic behind their creation, hence the need for rigorous study.

In practice, of course, the line between respectful imitation and cultural piracy is fuzzy, and it’s hard to see how his fireplace with mummy caryatids or his clock mounted on the head of a breast-festooned Artemis of Ephesus3 lands on the side of righteousness. Not to mention that the roads leading to Rome were paved by slavery and conquest. These are quandaries that rile cultural politics today and still stubbornly refuse resolution, no matter how diligently we acknowledge dispossessed peoples in our e-mail footers. All of which is to say, three hundred years on, Piranesi still has the power to provoke.

Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi? Watch this space.

-

1

“Piranesi and the Modern,” September 9, 2022–January 8, 2023. ↩

-

2

Bloomsbury, 2020; reviewed in these pages by James Walton, April 8, 2021. ↩

-

3

The sacs that characterize ancient Artemis of Ephesus figures have been variously identified as breasts, testicles, or eggs, but Piranesi drew his with nipples. ↩