At the Starbucks Reserve Roastery in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, the giant wooden front doors swing open to reveal the company’s sprawling, multilevel temple to itself. The space, which contains a cocktail bar, a gift shop, and a bakery in addition to a café, is done up in walnut and leather, with tastefully displayed industrial machinery. The presiding deity is an enormous copper statue of the Starbucks mermaid bursting from a wall, unless we’re meant to worship the smaller, shinier, bug-eyed mermaid statue for sale in the shop for $4,500.

Last autumn, on the third day of a strike over unsanitary conditions in the Chelsea café, workers on the picket line seemed to take particular glee in puncturing the Roastery’s carefully controlled image of luxury. “Do you want some bugs with your dessert? I’d be glad to help you out,” one baker said to passersby cheerfully. “Only fifteen dollars for mold with bedbugs.”

In April 2022 the Roastery became the first Starbucks in New York City to unionize. Seven months later Starbucks was refusing to begin serious contract negotiations with the location’s employees. I wondered, standing on the sidewalk, if the strike was mostly tactical, an attempt to shame the company into coming to the table. But Owen, a nineteen-year-old who has worked at the café for a year and was a member of the original unionization committee, told me that it was about workers coming together to address serious workplace concerns. There were ongoing complaints of mold in an ice machine, he said, and bedbugs had been spotted twice. Management insisted there wasn’t an infestation.

Management’s handling of the bedbug complaint reminded Owen of its tepid response to a Covid surge among workers in December 2021. “They waited until it was too late, until all of us had Covid. That’s kind of what they’re doing now,” he told me. Starbucks cultivates a progressive image and offers its employees (or “partners,” as it insists on calling them) more benefits than other fast-food chains, but during the pandemic many workers were radicalized by the dissonance between the company’s stated values and the disrespect they felt as they worked frantically in skeleton crews to keep the cafés running with no extra pay. Since December 2021 nearly three hundred Starbucks cafés around the country have voted to unionize. The company has tried to crush the union by a variety of means, including closing unionized locations and firing organizers.

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has issued over eighty complaints against Starbucks. From mid-2021 to mid-2022 it faced more NLRB cases than any other private employer, by a 30 percent margin. (One New York judge described their actions as “egregious and widespread misconduct.”) This past March Senator Bernie Sanders hauled Starbucks founder and on-again-off-again CEO Howard Schultz before the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee under threat of subpoena to testify about the company’s labor violations. In the hearing, Schultz denied that Starbucks had broken the law in any way; refused to promise that he would expedite contract negotiations with workers at the first unionized café, who had been waiting over 460 days for a contract; and objected to the term “billionaire.” “Yes, I have billions of dollars,” he said. “I earned it. No one gave it to me. And I’ve shared it constantly with the people of Starbucks. And so anyone who keeps labeling this billionaire thing…. It’s your moniker constantly. It’s unfair.”

Last fall, although Starbucks was unwilling to start bargaining and worker turnover was high, Owen said he felt encouraged by the community’s support. Local politicians visited, and UPS refused to deliver packages to the café during the strike. “Some partners are a little bit anxious, like myself,” he said. “But you realize that it’s gone too far and you’re the one that has to make the change.”

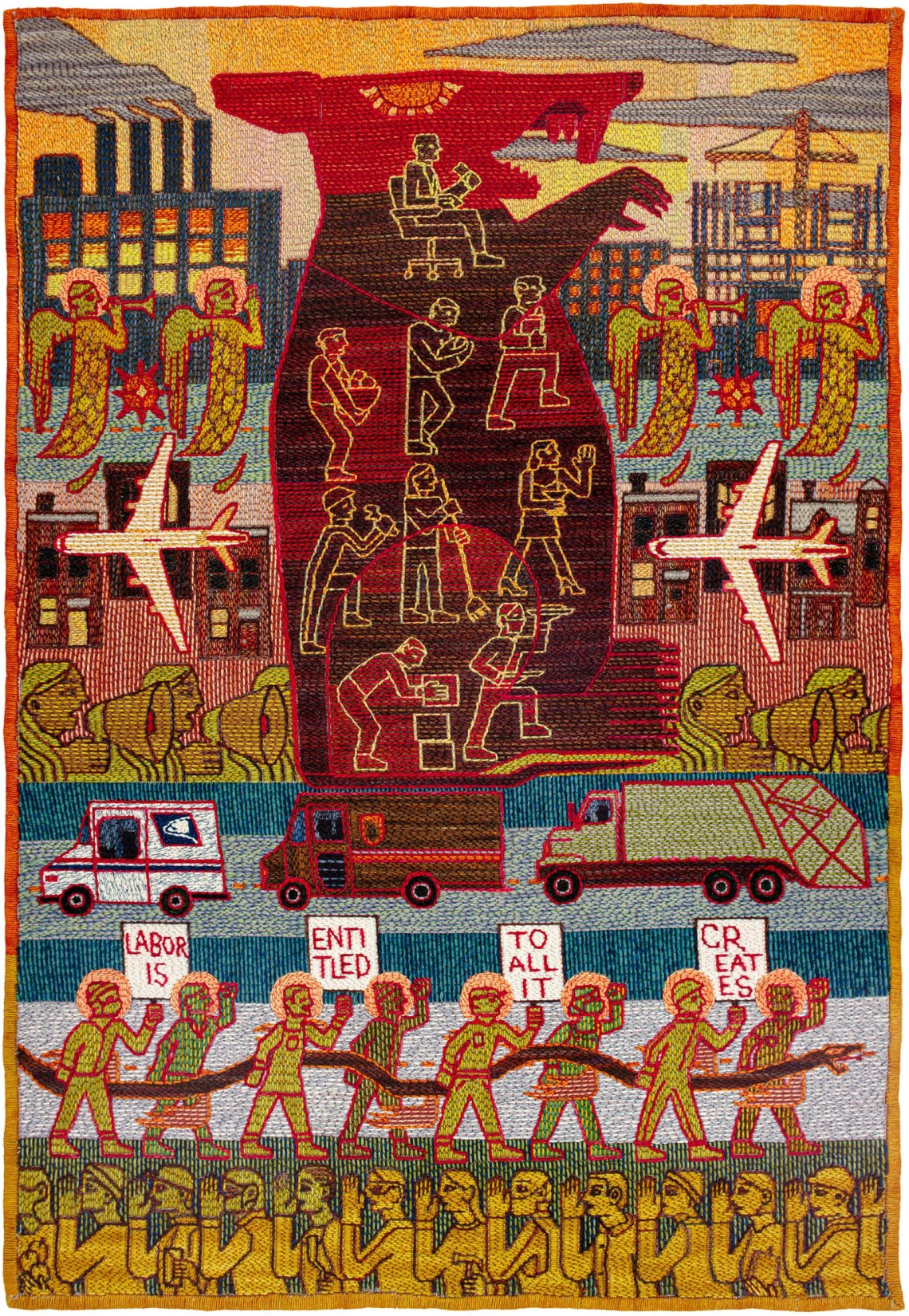

For our economy to function in its current form, hourly workers must toil at unpleasant jobs for very little money. Nearly a third of the US workforce makes less than fifteen dollars an hour—40 percent of female workers, 47 percent of Black workers, and 57 percent of working single parents. A number of recent books about low-wage work show the human misery behind that status quo. Together they describe a system that may well be nearing a breaking point. From this instability has grown some of the most high-profile grassroots labor organizing in decades. While the success of the movement is far from certain, it may offer the only way out.

The story of this crisis is a long one. It could start as early as the 1930s, when agricultural workers and domestic workers, who were predominantly Black, were excluded from laws that enshrined a minimum wage and the right of workers to organize. Or in the late 1950s, which marked the beginning of a steady shift in private-sector employment from producing goods to providing services, as the country moved away from a manufacturing economy. Or in 1981, when Ronald Reagan fired over 11,000 striking air traffic control workers, signaling to business owners that strikebreaking was not only politically acceptable but admirable. In Essential, an account of the labor market during the pandemic, the sociologist Jamie K. McCallum highlights the effects of the Great Recession of 2007–2009: midwage jobs made up 60 percent of those lost and only 22 percent of those that came back during the recovery. “We put people back to work, mostly as fast-food workers and in care services—almost seven million jobs that paid under $25,000 per year,” McCallum writes.

Advertisement

It was also around this time that the gig economy was born. (TaskRabbit was founded in 2008, Uber in 2009.) Gig companies receive a lot of media attention because they seem to have pioneered a new kind of work that severs the relationship between employer and employee. But more traditional employers, from government agencies to airports, have been doing something similar for years, subcontracting jobs like cleaning and security to the lowest-bidding firm. In the service industry, major chains like McDonald’s evade responsibility for violating workers’ rights by franchising their restaurants to private owners. “There are so many industries where employers just aren’t interested in workers anymore,” Kirk Adams, former executive vice-president of the large and influential Service Employees International Union (SEIU), explained to me in an interview. “They don’t want to be the employer.”

Low-wage work itself has changed, too. “Nearly everyone with influence in this country, regardless of political affiliation, is incredibly insulated from how miserable and dehumanizing the daily experience of work has gotten over the past decade or two,” writes Emily Guendelsberger in On the Clock. In the mid-2010s she worked at an Amazon warehouse in the months before Christmas, at an outsourced customer service call center, and at McDonald’s, jobs that she sees as representative of the “future of work” in their use of surveillance technology and algorithms to monitor and manage employees.

Among the most revealing sections of the book are her accounts of surreal orientations, in which she and other recent hires were given cheerful but blunt overviews of the hardships they could expect in their new jobs. “Another day in paradise!” begins her Amazon trainer, a recent immigrant from Cuba and a former warehouse worker himself. After explaining that employees will be on their feet for eleven hours per day, he describes the draconian attendance policy. Workers accumulate points for being slightly late or missing shifts. Six points and you’re fired.

“Let’s say it’s Saturday, 4:00 PM. You’ve been working since Tuesday. You think you cannot make it anymore, your feet are killing you, you want to go home. And you’re free to go home!” Without pay, and at the cost of a point, of course. This luxury can’t be indulged too often, because, as the trainer explains, there are very few exceptions to the six-point rule: “I have a doctor’s appointment, I have court—it has to be more serious than that.” When he discusses the importance of rest, he seems to veer off script: “The funny thing about it is that, where I come from, they talk about this country as the American Dream. Then we come here and we find out we cannot sleep!”

Guendelsberger finds that all three jobs have little forgiveness for the inefficiencies of the human body. At Convergys, the call center, if she takes more than thirty seconds off the phone, including to go to the bathroom or recover from being berated by customers, the time is tallied and deducted from her day’s wages. At McDonald’s her restaurant is chronically understaffed to ensure that workers operate at top speed, and she is instructed not to keep customers waiting for an order for more than one minute. At Amazon a handheld scanner sends her to collect items in the warehouse along routes that seem to keep her intentionally isolated from other workers and tracks her pace to the second, alerting a manager if she takes too much “time off task.” Guendelsberger calls these “cyborg jobs”—so highly routinized and technologically monitored that they seem to be halfway automated.1

In the 1950s and 1960s, an era of union strength, it was common to fight “speedup,” sometimes by including clauses in contracts that allowed workers to go home after finishing a set amount of work or just to relax in the breakroom. Reading Guendelsberger’s descriptions of Amazon workers popping painkillers under banners hung throughout the warehouse that say “WORK HARD. HAVE FUN. MAKE HISTORY,” it’s clear what happens when workers lack the power to advocate for the importance of rest.

Advertisement

Then came 2020, when an employment system built for cyborgs collided with mass human vulnerability. In Essential, a forceful and deeply researched book drawing on interviews with hundreds of workers, McCallum recounts wrenching stories about the danger essential workers faced and the callousness of their employers during the first few months of the pandemic.

Yok Yen Lee, a sixty-nine-year-old greeter at a Walmart in Quincy, Massachusetts, went to work with Covid symptoms while her request to take some of her meager number of vacation days was pending approval, having already used her sick days earlier in the pandemic out of fear of contracting the virus. She died about a week later. Lee’s daughter Elaine sued the company for worker’s compensation. Quincy’s health commissioner argued that Walmart had not been complying with quarantine or isolation guidelines or sharing contact information for their numerous infected employees. Walmart settled for a small amount in addition to sending Elaine, in her words, “a little plant…a fuckin’ succulent.” In Kathleen, Georgia, when workers walked out of a Perdue chicken processing plant in protest of unsanitary conditions and no hazard pay, the company gave them one free chicken breast each.

In the early stages of the pandemic, essential workers were publicly valorized throughout the country, with nightly tambourines and applause from city balconies, even as their employers were endangering their lives. McCallum finds that many workers resented being extravagantly praised but still denied basic protections. “The hero cult allows us to be put in harm’s way,” one Trader Joe’s worker told him. “It’s not that it’s not true, it’s that it assuages the guilt of society for not doing enough to protect us.”

This dissonance, McCallum argues, helped create a “frontline class consciousness” that spurred a wave of labor agitation. “The language of being ‘essential,’” he writes, “was almost always part of the rhetoric of protest.” In 2020, owing to the general chaos and the closure of much of the economy, major strike activity dropped precipitously from the previous two years. But there were smaller bursts of labor unrest, often in unexpected places. In addition to the thousands of nurses who went on strike that year, grocery-store workers, fast-food workers, bus drivers, and meatpacking workers engaged in work slowdowns or stoppages. The historic union win at an Amazon warehouse on Staten Island began with a walkout led by Chris Smalls over concerns about the spread of Covid in March 2020. Many of these protests were fleeting. “About one-third of the strikes during 2020 were led by workers without unions, which probably limited their effectiveness,” McCallum writes. But the fact that there were so many spontaneous labor actions in nonunionized sectors does suggest an untapped energy, an urgency brought on by the strain of the pandemic.

When the country began to reopen, service industry workers at restaurants, grocery stores, and airlines were tasked with enforcing Covid protocols, which often left them vulnerable to anger or violence from customers. The first half of 2021 brought a labor shortage that the media dubbed the Great Resignation, especially concentrated in the health care and service industries—some of the jobs most affected by Covid. Prices, meanwhile, went up and up, and amid concerns over inflation, public sympathy for frontline workers largely evaporated. Both business owners and economists admonished workers for not returning to their old jobs in full force and blamed economic instability on wage increases. By fall simmering discontent boiled over in larger strike actions—quickly christened “Striketober” on social media and in the press—in a number of already unionized workplaces like John Deere, Kellogg, and Nabisco plants. It was an active year for labor, but far from the revolution it might have seemed to be on Twitter: overall union membership continued its decades-long downward march.

How best to move forward? Labor law makes traditional organizing in any sector extremely challenging.2 Employers can submit employees to mandatory, hours-long “captive audience meetings” in which they disseminate anti-union information during work hours. In 2019 nonemployee union organizers lost the right to enter even parts of the workplace open to the public. It is illegal to fire an employee for organizing or expressing union support, but employers frequently do it anyway because essentially the only penalty is that they need to reinstate the employee and pay them back wages—minus any amount of pay the worker earned from another job in the often lengthy interval between being fired and getting a decision from the NLRB.3 Last December Joe Biden, the self-declared “most pro-union president you’ve ever seen,” crushed hopes for a genuinely monumental rail strike by signing legislation forcing over 100,000 workers to accept a contract with no sick leave.

In On the Line, the organizer Daisy Pitkin shows just how daunting these obstacles are in practice, and how much they limit what unions can legally achieve. The book is a gripping account of her first union campaign, spent organizing industrial laundries in Arizona in the early 2000s. When most workers at one plant signed union cards, the parent company, Sodexho, launched a vigorous anti-union campaign. In the process it committed a host of labor-law violations, firing pro-union workers and threatening to cut wages and benefits and to refuse to bargain if the union won. Pitkin addresses the book in the second person to one of these workers, Alma, who became her close friend and organizing comrade. The stylistic choice initially grates but begins to feel more justified once the reader absorbs the sheer number of hours the two spent together crisscrossing Phoenix, talking to workers and strategizing, nearly to the point of breakdown.

The workers lost the election and filed a complaint with the NLRB, which ultimately issued a rare ruling—“the judge found that the company violated the law so egregiously that there could never again be a fair election in the factory”—and mandated that Sodexho recognize the union. But the company appealed, and Pitkin learned that the legal process would take years to resolve. The SEIU and Pitkin’s union, UNITE-HERE, ran a public pressure campaign that resulted in a bargain with Sodexho: it agreed to accept the union if Pitkin and Alma could again muster most of the workers, which took another herculean feat of organizing.

We learned in the days after winning the card count that the national agreement between the union and your company had included a prefabricated contract, one that left only small pockets of space for what the negotiator called “local nuance.”…It was difficult to look at those words, to know that they were what remained after years of promising workers that you would bargain the contract, that you would decide what changes to prioritize, what to fight for.

The contract was quickly ratified, but both Pitkin and Alma were demoralized and burned out. The feeling intensified after months of public, bitter infighting between two factions in the union as the result of an unwise, top-down merger. Several years later, after Pitkin left organizing, she got back in touch with Alma and learned that she had been injured in a car accident, which made it impossible for her to do strenuous physical work. The laundry put her on indefinite leave with no pay, and the union was either too weak or too complacent to press charges.

Organizing in the service industry can be even more difficult. Some workers, including domestic workers, are still excluded from the NLRB’s protections. Parent companies of franchised restaurant chains can shut down individual locations if there is a whiff of union organizing by workers. Many service-industry workplaces have very high turnover, which is often intentional on the employers’ part. (Guendelsberger emphasizes the astonishing churn of employees at all the jobs she took.) Workers are often undocumented or divided by language.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, with union power declining, community-led groups called worker centers emerged to serve workers in especially underorganized sectors. Their numbers increased steadily over the next decades to about 250 today. They are exempt from some of the restrictions placed on unions, like limits to picketing, and often emphasize immigrant or racial justice, embracing workers who were historically excluded from collective bargaining laws or from unions themselves. Together these groups are known as the “alt-labor” movement, a term coined in 2013 by the journalist and former organizer Josh Eidelson. Some behave like informal unions, bringing workers together to negotiate with their employers about workplace conditions. Others operate at a broader scale, advocating for pro-labor legislation at both the local and national levels.

At their best, worker centers are creative and vigorous, and draw on the strength of radical organizing traditions in the communities they represent. A drawback is that they can’t raise money consistently from members in the way a union can, and sometimes depend on fundraising from donors like the Ford Foundation. In Class Struggle Unionism, the veteran union negotiator and labor lawyer Joe Burns argues that the worker-center movement “originates largely outside the working class and is not self-sustaining. For that reason, it can never replace the labor movement.” A lack of worker leadership can be a problem in unions as well—Burns argues that middle-class, highly educated staffers who are divorced from the concerns of those on the shop floor have come to dominate too many unions. But he maintains that the financial and legal structure of unions, in which leaders must be elected, provides a baseline level of democratic governance that is missing from worker centers. Even so, most worker-center organizers see their role not as replacing unions but as recouping some rights for their members. Often worker centers and unions work together, or unions use alt-labor tactics like advocating for workplace policy change.

In 2002 Saru Jayaraman cofounded a worker relief center called the Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC). At first intended to support the surviving staff of Windows on the World, the restaurant at the top of the World Trade Center, it soon grew into a larger organizing hub for restaurant workers. Since its inception, ROC has won over $10 million in back wages and settlements and led local policy campaigns for benefits like paid sick leave, and it now has 65,000 members. It also displays some of the limitations that Burns describes. In his 2008 book The Accidental American, Jayaraman’s cofounder, Fekkak Mamdouh, reports that its initial name was Restaurant Organizing Center, but that a union staffer advised Jayaraman that the name would be

too confrontational, and that it aroused the hostility of foundations, employers, and government. Saru went back to the group, and they replaced “organizing” with the all-American “opportunity.”

Jayaraman left ROC in 2019 to focus on policy as the head of the advocacy group One Fair Wage. She often works in that capacity with Fight for $15, a national campaign for a fifteen-dollar minimum wage launched by SEIU in 2012.4 The federal minimum wage of $7.25 hasn’t been raised since 2009, when it was worth over 40 percent more than it is today. Yet in her recent book One Fair Wage, Jayaraman identifies a surprising breadth of workers who are excluded from even this meager protection: gig workers, incarcerated workers, disabled workers, youth workers, and tipped service workers, who in sixteen states can be paid as little as $2.13 per hour by their employers. The book’s introduction and conclusion have the brisk tone of a white paper, and Jayaraman hammers home the title’s imperative—to pass legislation that requires, without exceptions, a fifteen-dollar minimum wage for all. But most of the book consists of moving testimonies from workers, and their accounts of life at the bottom of the US labor market touch on issues far beyond what could be addressed by a single, or even several, laws.

There’s the Uber driver in Philadelphia who has a mental breakdown after becoming mired in debt: having fallen behind on car payments after a bout of the flu with no paid sick days, he had his car repossessed and incurred hundreds of dollars in fees. Initially drawn to the job for its promised flexibility, he says, “I’m doing it now out of necessity, because I have nothing else.” There’s the man in Illinois who was sentenced to life in prison for aiding and abetting two murders committed by his older brother’s friends by stealing a car for them as a sixteen-year-old; he worked in the prison kitchens eight hours a day, six or seven days a week, at thirty dollars per month, subject to disciplinary action if he refused: “I didn’t want to miss a [college] class offering, but they drafted me to come work in the kitchen. I didn’t want the job, but I had to work it.” There’s the nail-salon worker in New York City, fearful of speaking up about wage violations and harsh conditions because of her immigration status. “Here I’m a slave to the job, to the bills,” she says. “You don’t have your own life, you don’t have a social life. Here it’s just work, job, children, seven days of the week. There are no days off…. You can’t live like this.”

Jayaraman’s book focuses most extensively on the pernicious effects of a tipped wage on service workers. She writes that the European practice of tipping, which Americans in the nineteenth century derided as aristocratic and encouraging of servility, didn’t catch on in the United States until after the Civil War, when Black people and women joined the service industry in large numbers. Nonwhite and female workers still make up a disproportionately high percentage of those whose wages depend on tips, and they live at higher levels of poverty than the rest of the workforce. Being subject to the whims of their customers means that Black workers make less than their white counterparts and that women have to humor a constant stream of sexual harassment if they want to be paid. During the pandemic, hundreds of women reported being asked to pull down their masks so that men could see their faces and tip accordingly.

One Fair Wage has passed bills and ballot initiatives to end tipped wages in Washington, D.C., and Michigan. (The group also passed a ballot measure in Maine, but it was overturned by the legislature; implementation of the Michigan bill has been complex and is currently awaiting a decision from the state’s supreme court.) Its Raise the Wage Act was incorporated into Biden’s Covid stimulus bill and passed the House but stalled in the Senate. Counting on such policy changes to improve workers’ conditions has its downsides. “In moving the conflict out of the workplace and into the political arena, alt-labor groups have swapped one set of formidable challenges for another,” the political scientist Daniel Gavin writes in a report for the Economic Policy Institute. It’s difficult enough for small groups to pass pro-labor laws in the face of powerful industry lobbying, but once the laws are passed, there are often too few inspectors to adequately enforce them, whereas a union is embedded in the workplace and can constantly monitor for violations.

Employers are supposed to make up the difference if tips don’t bring their employees to the full minimum wage, meaning that technically it isn’t legal for tipped workers to make $2.13 anywhere (a significant detail that Jayaraman skims past, writing that compliance with this law is “nearly nonexistent” without citing any specifics). For workers to make less than the federal minimum is wage theft, which is rampant in a variety of forms in the service industry. In a chapter on nail-salon workers, one woman describes working for a flat rate of fifty-five dollars a day, seven days a week. Her employer, she reports, told her to lie about the salon’s working conditions to Department of Labor investigators. Her testimony and those of many other workers in Jayaraman’s book reflect problems—the hotly contested contractor status of gig workers, the forced labor of prisoners, the vulnerability of the undocumented—that clearly require broader solutions than just raising the minimum wage.

The glimmers of hope in this section come from organizing. Some of the woman’s colleagues are part of an association of nail-salon workers affiliated with the SEIU:

“They’ve taught me a lot,” says one. “We didn’t know our rights. Now we learned it all, we can demand something. Demand our rights. Demand time to eat lunch. It’s not the same as before. Before when they said you have to hurry I had lots of fear, thinking, ‘They’re going to fire me.’…I’m able to tell other coworkers to not be afraid.’”

And yet the book ends with a rallying cry not for workers to come together but for “consumers across America” to take action. Jayaraman suggests three steps:

(1) Contact your legislator…. (2) Support restaurant owners who have been championing One Fair Wage and increased equity in restaurants…. (3) Encourage your favorite restaurant owner to join the fight for equity.

Having just read one devastating story after another about the travails of service-industry workers, one has trouble feeling optimistic that change will come from right-minded restaurateurs.

None of this is to understate the importance of raising the minimum wage by whatever means may be effective. “Eight to fifteen is a big deal,” Kirk Adams told me. “Try living on eight dollars per hour. It changes everything—what you can do with your time off, with your family.” A federal minimum wage increase would be a tremendous achievement, but it seems extremely unlikely to pass the deadlocked Congress. (It was, however, heartening to see Nebraska voters embrace a fifteen-dollar minimum wage pegged to inflation during the 2022 midterms.) Fight for $15 has successfully raised wages for approximately 26 million workers, but the campaign hasn’t translated to a large increase in SEIU membership, which was part of its original intention. Adams told me the SEIU was able to build power in sectors where they already had inroads, like home health care and nursing homes, but wasn’t able to engage restaurant and retail workers at the scale it had hoped.

This is why the recent wave of union drives in those very industries is all the more surprising. Starbucks isn’t franchised, which makes organizing easier than at other chains, but it nonetheless provides an example of how unionization is possible in fast food. When workers are in the lead, they can organize quickly store by store—a feat that a more top-down union campaign could only accomplish by expending significant time and resources to send in staffers. There have been successful drives at REI, Trader Joe’s, Apple, Chipotle, and of course Amazon. There have also been major losses, and it remains to be seen if these small, independent unions will be able to bring their powerful, lawbreaking employers to the table. But in sectors where little else has worked, grassroots organizing can’t be called an unrealistic strategy.

Both Pitkin and McCallum offer reminders that the worker protections of the 1930s were won only through militant striking. “Labor law reform won’t facilitate mass organizing,” McCallum writes. “It will result from it.” Many service-industry jobs are not as strategically placed as autoworkers were in the 1930s, but the pandemic made clear how integral grocery-store workers, care workers, and warehouse workers are to a functioning society, and union campaigns can build particular momentum at large chains familiar to the public. Burns, too, argues that the only way forward for unions is an increased militancy and willingness to strike, with a stress on worker leadership and an explicit class politics.

There are signs of growing radicalism beyond low-wage industries as well: in November 48,000 workers in the University of California system went on strike, the largest at an academic institution in US history, and a strike of 9,000 Rutgers faculty members ended on April 17 but may resume. After corruption scandals and declining membership, the United Auto Workers implemented a more directly democratic election structure, and a slate of candidates promising to take a more confrontational stance with employers won every race they challenged, including the presidency.

Pitkin doesn’t mention in On the Line that she’s now a lead organizer on the Starbucks campaign, but the job sounds like a good match, given her respect for worker-led organizing. In an October interview with the podcast The Dig, she described the campaign as the most self-directed she’s ever seen. Part of what makes this approach possible, she observes, is the strong community built by the many queer and trans workers at Starbucks: “From the beginning of the campaign, it’s already a community defense project.”

Cee, thirty-two, a bartender in North Brooklyn, wasn’t certain that Starbucks provided much of an example for his own workplace, which, like other restaurants he has worked at, was hierarchical and divided along class lines. “Unless there’s a clear culture of camaraderie, you’ll have front-of-house people who respect the head chef,” he told me. “But do they really know the names of the dishwasher, the people doing the prep work down in the basement in the back, and if they do, how much do they talk to them?” It also seemed to him that many of the Starbucks workers were college educated, which he imagined shaped their politics and exposed them to ideas about unions. When he had discussed asking for more benefits with his coworkers, they were polite but noncommittal, more inclined to keep their heads down.

“People are doing their damnedest to understand what’s going on in the world,” he said. “Why is my check like this, or why am I angry, or why am I scared? I’m hopeful that people will start unionizing a little more over the years, but there’s that fear you have to get over.” Overcoming this fear through community-building, and reclaiming the humanity that employers ask workers to leave at home: this is the stuff of organizing. Cee had some plans:

I have to learn Spanish, to increase our ability to communicate. Even hokey things like doing barbecues, going to do garden work together: solidarity is contagious. It’s almost an automatic thing—who you spend time with, you empathize with.

-

1

For more on worker surveillance, see Zephyr Teachout, “The Boss Will See You Now,” The New York Review, August 18, 2022. ↩

-

2

For more on the assault on unions, see Jane McAlevey, A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (Ecco, 2020). ↩

-

3

A December ruling by the NLRB found that employers are liable for “direct and foreseeable” financial harms suffered by an employee as the result of an illegal firing, such as out-of-pocket medical expenses. ↩

-

4

For more on the inception of Fight for $15, see Steven Greenhouse, Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labor (Knopf, 2019). ↩