None of this had to happen. In the fall of 2008, amid the great shipwreck of the international financial order, an anonymous person or group of persons writing under the name Satoshi Nakamoto proposed a new electronic cash system called Bitcoin. In the “white paper” proposing the system, initially circulated to a cryptography mailing list, Nakamoto claimed that it would “allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.” In order to avoid the problem of users spending the same intangible electronic cash twice, Nakamoto proposed something called a “distributed timestamp server,” now generally known as a “blockchain,” which is a kind of digital ledger. Anytime someone made a payment, it would get added to the ledger, and the ledger would be a permanent, open, transparent record of all payments. Unlike banks, there would be no central repository, no single authoritative copy of the ledger. Instead, every participant in the network would hold a copy.

When a transaction happened, the participants would race to do the difficult computational problems the system required to verify it relative to all previous transactions in the ledger, and the first participant to verify would be awarded with new bitcoins. This system is called “proof of work.” In this way, new bitcoins would slowly be created, or “mined,” up to an eventual limit, because the computations needed to verify the chain of transactions would continually require more and more processing power, gradually driving the production of new coins to zero, which would also eliminate the potential for inflation. With no centralized authority there was no bank that could fail—and no CEO to prosecute. Thus from the ruins of 2008 was cryptocurrency born.

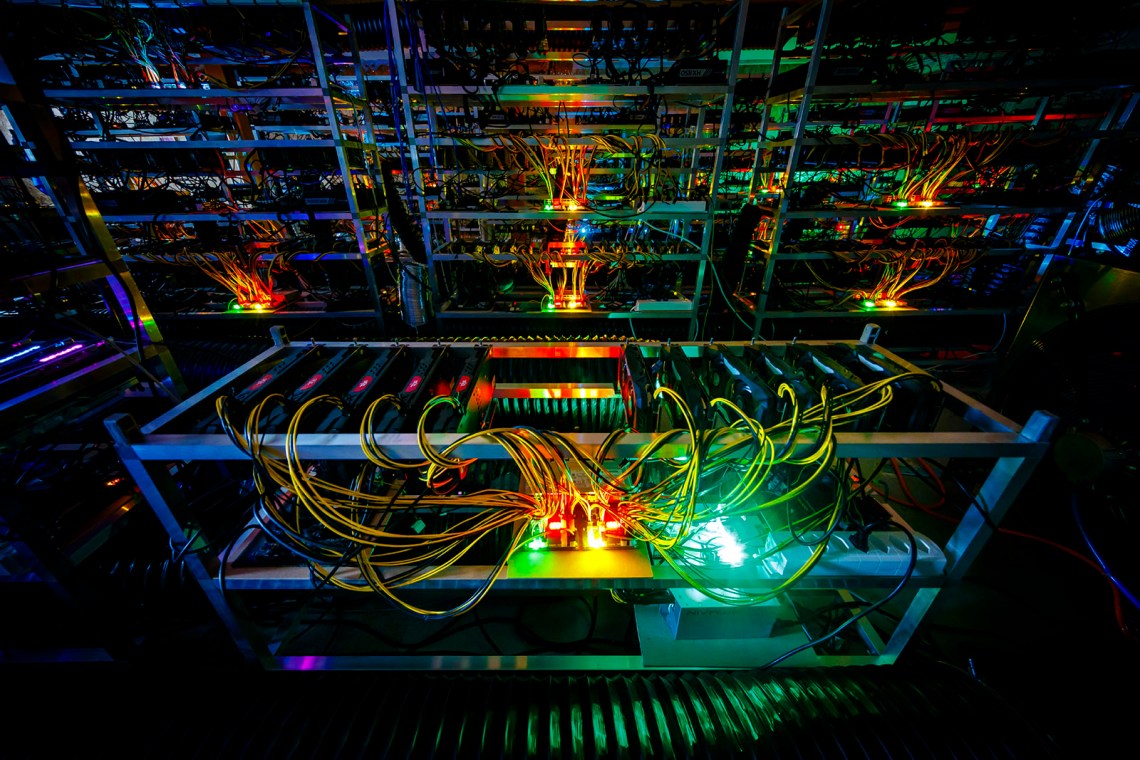

But Bitcoin (the network is capitalized, the “currency” is not) was and is terrible. Proof of work meant everyone in the network raced to verify every transaction, but there could only be one winner, generating a huge amount of wasted, redundant effort and truly appalling consumption of electricity and computer chips as participants engaged in an arms race to build bigger and more powerful computers. The network could process just a few transactions per second, relative to thousands for companies like Visa, and some transactions could take hours, during which time the price of bitcoins, and thus the value of the transaction, could change.

Cashing out and returning to real money has also been very difficult: bank fraud officers look askance at untraceable anonymous transactions. For those reasons, Bitcoin was of limited utility: a speculative investment for some who watched its price oscillate, and a means of payment for people doing things that were so illicit that the slow transactions, unpredictability, and illiquidity were worth it. In late 2013 the FBI shut down Silk Road, the main online black market, meaning bitcoin holders couldn’t even buy drugs anymore. It could have all ended then.

While Bitcoin was running into technical and legal constraints, a nineteen-year-old computer programmer and writer for Bitcoin Magazine named Vitalik Buterin had an idea for expanding and generalizing the cryptocurrency technology to more aspects of economic and social life. He announced his Ethereum project in early 2014, and since 2018 it has been the second-largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization, after Bitcoin itself.

Like Bitcoin, Ethereum has its own currency, ether, but it has two crucial innovations: “proof of stake” and “smart contracts.” Proof of stake is the easier of the two to explain: instead of the wasteful and redundant proof-of-work system, Ethereum transactions are verified by a lottery of the users who have deposited collateral (stake), with larger deposits increasing the odds of winning. That system has the advantage of eliminating the redundant calculations but means that players with a lot of cash to deposit are continually rewarded with new ether, and it introduces a bottleneck, since transactions have to go through relatively few verifiers. Between 2020 and 2022 Ethereum switched completely to proof of stake, which the developers claim has reduced their electricity consumption by 99 percent—before that, the network was using about as much electricity as Finland.

Smart contracts are a little more difficult to understand, because they are neither smart nor contracts. They are bits of computer code that automatically make something happen: upon receipt of X ether from person Y, transfer asset Z to person Y, for example. They are not (yet) legal agreements, although several US states have begun to pass legislation recognizing them. But they remain only occasionally and haphazardly enforceable. They are dumb in the way all computers are dumb: they cannot distinguish between intention and mistake, transaction and theft, bad inputs and good.

Buterin’s idea was that the Ethereum system could be applied to anything. The journalist Laura Shin, in her book The Cryptopians, provides this lucid example:

Imagine you wanted to create a decentralized ride-sharing network—an Uber-like network of cars without the company Uber. You mint a new cryptocurrency—let’s call it CabCoin—and create CabCoin’s fund-raising contract on the Ethereum network. The contract could be programmed to send out the new token to anyone who sent it ether, at some predetermined ratio, such as ten thousand CabCoins per ether. Holders of CabCoin could then use it to pay for rides or vote on changes to the network, such as the pricing, drivers’ wages, and the network’s marketing budget.

In a 2014 article for Bitcoin Magazine, Buterin claimed his project constituted “a new kind of ‘economic democracy,’” and explained it this way:

Advertisement

It is possible to set up currencies whose seigniorage, or issuance, goes to support certain causes, and people can vote for those causes by accepting certain currencies at their businesses. If one does not have a business one can participate in the marketing effort and lobby other businesses to accept the currency instead. Someone can create SocialCoin, the currency which gives one thousand units per month to every person in the world, and if enough people like the idea and start accepting it, the world now has a citizen’s dividend program, with no centralized funding required. We can also create currencies to incentivize medical research, space exploration, and even art; in fact, there are artists, podcasts, and musicians thinking about creating their own currencies for this exact purpose today.

His initial ideas were to use Ethereum for multisignature escrows, savings accounts, and peer-to-peer gambling, and he said that since any group of enthusiasts could use the technology to launch their own projects, the only limit was imagination. Soon Buterin thought the system could replace judges. At a convention in 2015 Christoph Jentzsch, the founder of an “Internet of Things” blockchain project who went on to help implement Ethereum, showed how he could “use Ethereum to control a lock that would enable people to rent out belongings to people who had paid. While standing at his laptop, he created a transaction that turned on an electric kettle several feet away.” Other blockchain peddlers claim it may be an ideal way to preserve shipping inventories, medical records, electoral counts, and property titles. In 2021 Francis Suarez, the mayor of Miami, endorsed a “MiamiCoin” for local transactions, with part of each going to the city government—though by May 2022 its value had crashed by 95 percent. Late last year Hillary Schieve, the mayor of Reno, Nevada, announced the first “city-run and resident-focused blockchain platform,” but maintained it had no relation to cryptocurrency.

The specific virtue of blockchain technology is supposed to be that it is inviolable: a permanent, add-only record of past transactions. But what if you make a mistake, or get hacked or tricked? The only way to undo a transaction is to persuade a majority of participants in the network to undo all subsequent transactions. Even if that happens, all participants may not agree, and the network may split in what is known as a “hard fork,” when one part of the network recognizes a change in the ledger and another part refuses it. The same applies if verifiers disagree on the validity or order of transactions. Or if a hacker takes control of some of the network—at 51 percent, they can effectively rewrite the rules. Or if the developers of the network introduce updates and not all participants accept them, something usually known as a “soft fork.” This problem not only eliminates most practical consumer protections with its irrevocability, but also means that disagreements over individual transactions can result in entirely separate narratives of economic reality.

Bitcoin hard-forked in 2013 when a glitch in the software prompted a sell-off. It hard-forked again in 2017 over a disagreement on resource demands, and one of the prongs of the split network (Bitcoin Cash) itself hard-forked in November 2018. Now imagine a blockchain containing your medical records or electoral rolls hard-forking and one of those forks hard-forking again.

Ethereum launched in July 2015. By late April 2016 the developers were ready to expand and created something called the DAO, a specific version of a general concept known as a “decentralized autonomous organization.” These are the organizational structures for the coin projects, something like a crowdsourced hedge fund. The DAO took in payments in ether and gave its members back tokens. Those tokens would ostensibly rise in value and conferred voting privileges. Anyone could make a project proposal to the DAO, and its token-holding members would decide whether or not to fund it. Whether this amounted to “economic democracy” or an unregistered hedge fund, it raised something like $150 million from tens of thousands of investors.

And then the DAO immediately hard-forked. On June 17 some still-anonymous attacker discovered a mistake in the code that allowed them to make the same withdrawal over and over, moving the proceeds into their own separate fund where they were the only voter.

Advertisement

Despite its claims to decentralization and democracy, Ethereum and its DAO project were the work of a small team of developers whose reputations and financial interests depended on its success. They rapidly mobilized to transfer out the remaining cash to a new fund with new rules that excluded the attacker. They rewrote the initial rules to lower the voting quorum, and persuaded the “whales” (the largest holders of their tokens) to vote in favor of a hard fork to undo the attacker’s transactions. Hard-forking won the vote by 90 percent, but only 5 percent of tokens voted.

Buterin and his Ethereum collaborators claimed that they were preserving the intentions and ideals of the project. Other people in the crypto world disagreed: by rewriting the blockchain, they had committed the cardinal sin of showing that crypto is not actually a decentralized democracy. Gregory Maxwell, one of the Bitcoin developers, wrote to Buterin: “If you rewrite the ethereum consensus rules to recover the coins you and others lost to the as-written execution of that smart contract, you show that the system is really controlled by political whim, in particular via you.” The attacker, meanwhile, wrote an open letter claiming that “a soft or hard fork would amount to seizure of my legitimate and rightful ether, claimed legally through the terms of a smart contract.”

Ethereum survived, at the cost of $700 million, which was some 41 percent of its market capitalization. The attacker’s prong of the network survived, buttressed by Ethereum’s enemies, and continues today as “Ethereum Classic.” Ethereum hard-forked twice more in 2016, and again temporarily in 2021. By one interpretation, Ethereum’s attempt to invent economic democracy through the blockchain showed yet again that constitutional legitimacy is difficult to secure and can lead to political schisms; by another, the repeated hard forks simply prove that blockchains are not inviolable, but rather unstable and subject to rewriting whenever it suits their owners.

The story of Ethereum’s founding, the 2016 hard-fork incident, and its survival through several subsequent hacks and scandals is all minutely told in The Cryptopians. Shin has interviewed all of the major players and most of the minor ones, and combed through thousands of e-mails, Skype chats, Slack channels, tweets, and Reddit posts. No one will ever tell this story again at the same level of detail, or want to.

There are at least fifty characters, referred to by first name, last name, nickname, or Internet handle. Shin introduces each person with a brief description of their hair and one other adjective. It is difficult to remember whether Gav is the lanky one with the tousled hair, or the boyish one with the unruly mop. These people lie to one another constantly, about whether they graduated from MIT, or were spies, or did or didn’t do certain professional tasks they’d agreed to do. In addition to haircuts, Shin has an interest in interior design, especially at dramatic moments. At a contentious meeting where a few founders are pushed out, we learn that the table “was made of six long and wide bleached-wood kitchen countertops arranged three by two, with thin gray streaks, laid on blond-wood workhorse-style table legs.” Later, as the Ethereum team gathers to respond to a major hack, “the pattern in the carpet looked like blank STOP signs chained together in rows.” And so on.

Shin clearly considers this story to be high drama populated by colorful characters, and there’s an inescapable sense that she hopes the book will one day be a film directed by Adam McKay. But it reads as an exhaustive catalog of the memories of a set of socially illiterate computer programmers having a series of IT problems and HR meetings. Thanks to the technical complexity of the subject, the dialect of crypto enthusiasts, and Shin’s very literal reporting, there are a lot of sentences like this: “In the 0x969 address, the attacker, who had spent 10 BTC, had amassed 25,805.61 DAO tokens (about $4,650) and 139 ETH ($2,724).” They are intelligible, but not for the impatient or the uninitiated.

Shin’s habit of uncritically transcribing the recollections of her interviewees sometimes approaches free indirect style. It is, for instance, unclear whether it is her opinion or someone else’s that Buterin “was more honest and pure than the others.” Whatever the case, she believes Buterin to have been the heroic idealist of the Ethereum world: socially awkward, perhaps, and conflict-averse, and not interested in the day-to-day grind of business management, but a brilliant thinker with a heart of gold. Buterin is indeed widely respected in the world of crypto for his psychedelic unicorn T-shirts, his apparent consistency even after his acquisition of wealth, and his donations to Ukrainian relief charities after the Russian invasion in early 2022. In an essay on free speech first published on his website, he claims that he wants to follow a social principle that “the ideas that win are ideas that are good.” So what are his ideas?

Proof of Stake collects that essay along with twenty-two of Buterin’s articles and blog posts written between 2014 and 2022, as well as the 2013 white paper proposing Ethereum. It has all the aesthetic qualities of a website that someone has printed out. It is introduced and lightly edited by the media scholar Nathan Schneider, but remains largely unintelligible unless the reader already knows the story of Ethereum and the language of the cryptosphere.

Buterin’s essays are full of attempts to use game theory to explain human behavior. He concludes that “it is cognitively hard to convincingly fake being virtuous while being greedy…so it makes more sense for you to actually be virtuous.” Later he tries to understand legitimacy, defining it as

a pattern of higher-order acceptance. An outcome in some social context is legitimate if the people in that social context broadly accept and play their part in enacting that outcome, and each individual person does so because they expect everyone else to do the same.

In each case, he tries to map out the game-theoretical logic of why virtue, honesty, and legitimacy are rational behaviors.

Like Nakamoto, Buterin argues that one of the most valuable properties of his institutional design is “trustlessness.” Trust, he believes, is “the use of any assumptions about the behavior of other people.” Again and again, he argues that crypto is a way of building a trustless utopia: rational, with institutions and actors replaced by markets, and never dependent on knowing or assuming anything about anyone else. But at the same time he, like the rest of the crypto ecosystem, constantly invokes “community.” The community makes decisions; the community confers legitimacy; forks and policies are accepted and adopted by the community. How do you build a community without trust? You don’t: Buterin has confused community with investors, users, and buyers. He cannot conceive of a community that is not bought, and he thinks the problem with other communities is that they are not run according to efficient market logic. Hence his project of moving beyond the pseudomonetary goals of Bitcoin to the organizations and social projects of Ethereum.

In addition to economic definitions of money, scholars like Christine Desan and Stefan Eich have argued that money is also a political technology: an expression of sovereignty, yes, but at the same time a representation of how a society is constituted as a set of ongoing negotiations between people and power. What kind of constitutional order does Buterin’s project reflect?

He calls it “futarchy,” which he defines as “a governance model in which voters choose certain social goals, and in prediction markets, investors bet on the policies they believe are most likely to achieve those goals.” It’s a kind of radical marketization of politics and, like Ethereum itself, one in which the coordination of a few “whales” can rewrite the rules as needed.

In her 2015 book Undoing the Demos, the political theorist Wendy Brown warned that neoliberalism was not just a package of free market economic policies but a system that remakes our understanding of democracy. Regardless of how you feel about the word “neoliberalism,” her description matches Buterin’s goals exactly: “Neoliberal reason…is converting the distinctly political character, meaning, and operation of democracy’s constituent elements into economic ones.” It reconfigures elements of democracy, including “vocabularies, principles of justice, political cultures, habits of citizenship, practices of rule, and above all, democratic imaginaries,” into market calculations.

By this she means that the hollowing out of democracy from a substantive idea based on solidarity, sacrifice, and mutual recognition into a set of formal procedures that equates buying with voting undermines not only democracy but the cultural preconditions for it as well. In their continual confusion of “community” with “investors” and voting with buying, in their continual application of game theory to social life, and in their entrusting of public policy to bets in prediction markets, Buterin and his comrades are an unreflexive demonstration of this entirely marketized subjectivity. When Buterin refers to spending crypto tokens as “economic democracy,” he is not only unaware of the long line of thought that considered socialism to be economic democracy; he is theorizing a cheap and hollow facsimile of democracy and revealing that he cannot even tell the difference.

But to say the political is eroded by the economic or that democratic ideas are converted to the rule of markets is not to deny that there really is a specific political content at work in crypto. Both Buterin and Shin move quickly over the fact that Ethereum was possible thanks to a $100,000 grant from the Thiel Foundation, which was founded and is funded by Peter Thiel, the PayPal billionaire, Facebook investor, and Donald Trump supporter who has written that he believes freedom and democracy are incompatible. Buterin likes to quote David Friedman, a self-described “anarcho-capitalist” who is incidentally the child of Milton and Rose Friedman, on subjects like virtue and rationality. The idea of “futarchy” is most closely associated with Robin Hanson, an economist at George Mason University and a proponent of prediction markets who, among other things, claims to have “invented a new form of government.” He did not: futarchy is a repackaging of nineteenth-century political systems that allocated votes proportionately to wealth, and “trustlessness” is an obsession of property owners who have come by their wealth in an especially illicit way.

The trouble with trustlessness, as Shin’s book shows, and as anyone who has read any news article about crypto has seen, is that crypto promoters actually trusted a lot of people, very much including people they shouldn’t have. They needed to trust one another in decision-making and liability, they needed to trust their programmers not to leave mistakes in the code, and they needed to trust other operators, especially at exchanges and in payment apps like digital wallets. Crypto exchanges are a necessary part of the ecosystem, because they are where prices are determined and where people can try to cash out. In 2014 Mt. Gox, then the largest exchange, was hacked and lost hundreds of millions of dollars before abruptly ceasing operations. The Cryptopians tells at least three stories of wallets and exchanges being hacked, including one case in which $150 million was locked in 587 wallets, potentially forever. Last summer’s crypto crash brought another exchange, Binance, under federal investigation. And of course in November 2022 FTX entered bankruptcy proceedings. One of the principal selling points of crypto is the allure of getting in on the ground floor of the next big thing. Don’t you wish you had bought bitcoins in 2009? Well, if you had, you probably would not be rich today. The FBI would have seized your bitcoins when it shut down Silk Road, or you would have lost them in the Mt. Gox hack.

Is cryptocurrency the future of money? No. Cryptocurrency is not money. The economist’s basic definition of money is that it serves three functions: it is a store of value, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange. Crypto does none of those things. Its price oscillates by two or three orders of magnitude, so it is far from a stable store of value. Further, there is no single price of ether or bitcoin: the prices are different on different exchanges. Because of crypto’s instability, it is not very useful as a unit of account: nobody wants to set prices or wages in bitcoin or ether if their dollar value varies widely. And because it is difficult to cash out and transactions are so slow, it is a medium of exchange only for illicit, expensive things or for other cryptocurrencies. Nor has it replaced banks, as Nakamoto claimed it would: banks conduct payments, yes, but they also match borrowers and savers, providing loans and finance. Bitcoin does not, and Ethereum’s attempt to do so with the DAO immediately showed why deposit insurance is a good idea, not to mention consumer protections, financial regulation, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Cryptocurrency is, instead, an unregulated speculative security. Shin helpfully explains the four points of the “Howey test” that the courts use to determine if something is a security and thus regulated by the SEC. A security is (1) an investment of money, (2) in a common enterprise, (3) with a reasonable expectation of profits, and (4) dependent on the efforts of an identifiable party. Crypto’s main strategy for avoiding regulation has been to claim that the fourth criterion does not apply: since the blockchain is decentralized, since decisions in a DAO are made by vote, there is no identifiable responsible actor. The story of the 2016 hard fork clearly demonstrates the falsity of that claim.

Can the speculation be stripped out and the underlying technology applied to city funding, medical records, and property titles? Even if it could be rescued from this pullulating hive of scams, hacks, and mendacity, and even if the nakedly reactionary politics could be set aside, the prospect of holding medical records on a transparent public ledger is not a good idea. The notion of tying municipal finances to proof-of-stake verification is patently oligarchic. Logistics companies may well want to track things, but they certainly do not want their internal workings to be public knowledge on a blockchain. Proof of work is environmentally disastrous thanks to the huge amount of electricity expended doing redundant calculations, and proof of stake rewards and increases inequality. The story of the DAO illustrates exactly why identifiable individuals with fiduciary responsibility to investors are necessary for corporate governance. There is nothing to salvage here.

Is the crypto bubble like other historical financial bubbles? Again, mostly no. The value of historical comparison should be to illustrate what is new and different, not merely to search the past for similarity to the present. As the historian Anne Goldgar has shown, the Dutch tulip mania of 1634–1637 was actually a minor affair (overblown by Anglophone writers who could not distinguish satire from reporting), and anyway, there really were real tulips, and they were beautiful. The world’s first international financial crisis, in 1720, did involve monetary innovation (the Scottish adventurer John Law pioneered paper money in France) and did involve speculators losing their investments in ridiculous schemes that were floated in London’s Exchange Alley. But the bubble was driven by real companies with real assets and real cash flow, each closely connected to political power, and each attempting to convert state debt into company stock. Even Charles Ponzi’s postage reply stamps really could be used for postal services, and he was a single, central, responsible entity.

In the past, anyone attempting to set up a speculative venture with no specified or tangible product, no cash flow, and no physical location would have had trouble drawing on global pools of investment liquidity. Anyone who succeeded on a local level would probably be flattened by fraud investigators. The crypto bubble is new because it represents a unique combination of technical complexity, internationally mobile capital, and regulatory arbitrage. It has been fueled by cheap electricity, cheap computer chips manufactured by cheap Asian labor, and above all more than a decade of cheap money from central banks.

Both Buterin and Shin end their books with optimistic invocations of NFTs: nonfungible tokens that were briefly a craze in late 2021 and 2022. They were another version of the Ethereum plan: entice people to contribute (which they did in ether, thus creating a new source of demand for crypto, another new set of buyers to help existing crypto holders cash out), give them a claim to unique digital ownership of something (usually a ghastly cartoon profile picture), and promise that “the community” would decide whether the pooled funds went toward creating a video game, a movie, or some other unknown project. Between the writing of these two books and this review, the NFT market has crashed so hard that services have appeared offering to buy worthless NFTs in exchange for tax write-offs. Such is the state of the crypto utopia.

This Issue

June 8, 2023

Getting Sacagawea Right

A Life of Sheer Will