1.

In 1997 I published an article in these pages1 in which I tried to draw some conclusions about the Chechen war of 1994-1996. In Moscow, the presidents of Russia and Chechnya had just signed a pact that rejected the use or threat of force and postponed a final resolution of Chechen-Russian relations until the year 2001. It seemed to me that the war was finally over and that the time had come to sum up recent events.

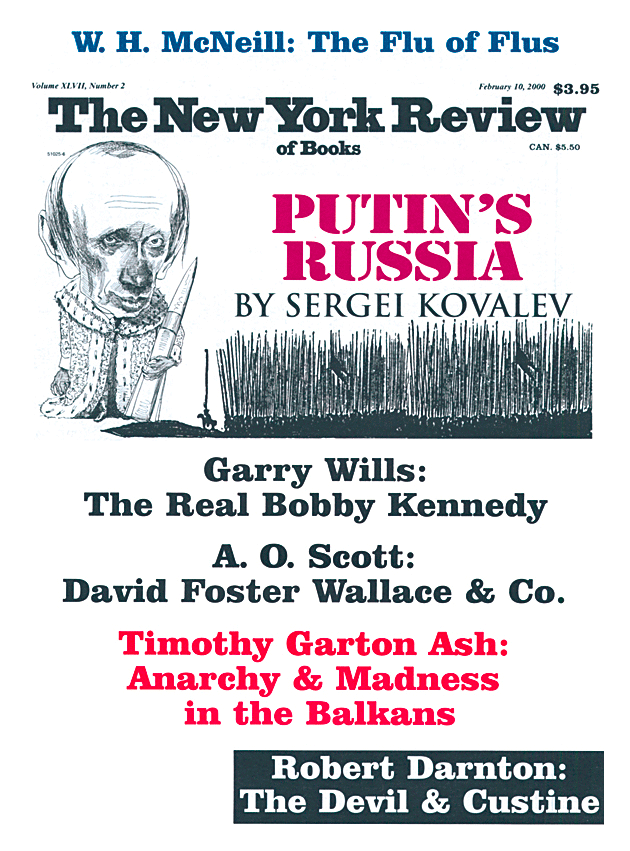

I was cruelly mistaken. However, at the time no one in his worst nightmare could have dreamed that there would be politicians in Russia who, being of sound mind and memory, would resume the Chechen war on an even greater scale than before. It was even more difficult to imagine not only that the war itself would be supported by the Russian public, but that it would result in unprecedented political dividends for the Russian leaders who presided over it, particularly Vladimir Putin, who owes his accession to the presidency largely to his backing of the war.

For American readers to fully understand how unthinkable a metamorphosis has taken place, let them imagine for a moment that in, say, 1978, the president of the United States resumed the war in Vietnam. And furthermore that this action was applauded by all Americans—from miners and farmers to university professors and students. Inconceivable? Of course it’s inconceivable. Nonetheless, this is precisely what has happened in Russia today.

First, I must make it clear that a huge share of the guilt for what has happened lies with the Chechen people and its leaders.

In the first months after the military action ended in 1996, it seemed that there was an opportunity to establish a democratic regime in postwar Chechnya, one that would act according to the rule of law. If that had happened it would not, in my view, have mattered whether Chechnya remained part of the Russian Federation or not. In January 1997, Aslan Maskhadov was elected president of Chechnya. Maskhadov was a moderate and responsible leader, a man who definitely preferred a secular model of development to an “Islamic state.”

Of course, there were serious concerns about Chechen behavior at that time. The extortion and violence against the remaining local Russian-speaking population, including kidnappings for ransom or enslavement, not only did not cease with the end of the war but increased many times over. And the new Chechen authorities made absolutely no attempt to stop this criminal activity, although in a country as tiny as Chechnya, with a population of fewer than one million people, everyone knew perfectly well which of Maskhadov’s former associates were making money on the slave trade, where the captives were held, how the ransom was extorted, and so forth. Yet after every reported kidnapping of a well-known victim, the president of Chechnya made public statements in which he explained events, in vague and extremely unconvincing terms, as “provocations by the Russian secret service.” There were hardly any attempts to rescue prisoners. There were no attempts to track down or to punish the organizers of these crimes.

The kidnapping of numerous journalists was particularly repugnant. These were people who for two years, at serious risk to their lives, had told Russia and the world the truth about the last war. Chechens were as indebted to them for the peace as they were to the military victories of the Chechen militia.

The result was not long in making itself felt: correspondents stopped traveling to Chechnya, and a completely new, diametrically opposed attitude toward the republic formed among Russian journalists. It is hard for me to reproach the journalists for hostility toward Chechnya.

Furthermore, the norms of Islamic law were introduced in Chechnya in a particularly harsh form, including corporal punishment, the amputation of limbs, and public executions broadcast on local television. All of this forced people friendly to Chechnya to doubt the sincerity of Maskhadov’s intentions to defend the secular nature of the state—intentions that he never stated publicly, by the way—or, at the very least, to doubt his resolve.

Unfortunately, the fears that I expressed about Chechnya’s future in my 1997 article turned out to be well founded. During the last three years, the president and government of Chechnya have not been willing to risk taking decisive measures to bring order to the republic. Their reasons are obvious—they were afraid that the first firm step they took would lead to an uprising and civil war. But Maskhadov’s timidity led to the worst possible outcome: almost complete loss of control over the country and the transfer of real power into the hands of the so-called “field commanders,” among whom are such people as the slave traders Arbi Barayev and Ruslan Khaikhoroyev, the terrorists Salman Raduyev and Shamil Basayev, and the Jordanian Islamic fanatic Khattab, who many assert is an ally of Osama bin Laden. The last vestiges of the system of state authority disappeared in the confrontation between the government and the field commanders.

Advertisement

In other words, the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria never actually came into existence—even as an “Islamic republic.” Instead, a black hole was formed on the world map out of which bearded people driving Kamaz trucks and carrying Kalashnikovs descended from time to time on the neighboring regions of Russia. Sometimes they would seize livestock and disappear with them, sometimes people. No one knows with any accuracy what actually happened within the territory of Chechnya itself.

What we do know is that Basayev and Khattab mounted in August a “liberation crusade” into neighboring Dagestan. Apparently, they and the other commanders of the Chechen units that invaded Dagestan saw themselves as “internationalist warriors for Allah,” Islamic Che Guevaras, one might say. They were certain that fellow believers on the other side of the border would greet them with open arms. They were mistaken: the Dagestanis met them with weapons. Even some Chechens—both in Dagestan and, it is said, in the border regions of Chechnya itself—attempted to stop the insane raid. They understood what the consequences would be. “You will pass only over our dead bodies,” they are said to have told Basayev’s and Khattab’s people. “No problem,” replied “Allah’s warriors.” So the informal Chechen rural patrols in the border regions let them through.

I have no right to judge peaceful peasants who yielded to heavily armed Islamic thugs. But had they known all the consequences of the Dagestan venture, many of them would, I believe, have preferred to risk death rather than let the Islamists cross the border. And if President Maskhadov could have foreseen all the consequences (and it was his job to do so), he would have done everything he could to prevent an incursion into Russia from the territory of Chechnya, even at the risk of civil war.

In Dagestan, for the first time since the end of World War II, the Russian army carried out a genuine mission of liberation. It protected the inhabitants of Dagestan from outside attack. The army did its work badly: it suffered losses from its own artillery fire and its own air strikes. For weeks it could not take several small mountain villages that had been captured by Basayev and Khattab; and it failed to warn the peaceful populations of these villages about its impending use of artillery and bombing. The Russian troops engaged in pillaging and violence against people in the liberated areas, although, in comparison with the previous war, their behavior was fairly moderate. In the end, however, the army fulfilled its mission. Some of the Islamist invaders were dispersed; others were forced back into Chechnya.

Apparently, at this point a monstrous idea was born in the heads of the army generals and Moscow politicians: to use the momentum of the Dagestan victory to unleash a new war with Chechnya.

It is easy to understand what the generals wanted. They wanted revenge for their shameful defeat in the previous war. The motives of the politicians are far more complex. I recently tried to describe some of them in the Berlin paper Die Welt:

For reactionary Russian politicians the resumption of the war is also a form of revenge, revenge against the “vile liberals” and the “irresponsible loudmouths” who in 1994-96 roused public opinion against the bloody demonstration of Russian state power.

But I am afraid that this interpretation was far too simplistic. I underestimated the level of cynicism pervading contemporary Russian political life. Of course, the “reactionary Russian politicians”—supporters of nationalist-patriotic groups and various factions of the Communist Party—would have been happy to dispose of the “vile liberals” as well as the decrepit Kremlin tsar, who authorized the cease-fire agreement at the town of Khasavyurt on August 31, 1996, and signed the pact in Moscow in May 1997. But they didn’t get the chance to do this.

The new Chechen war was used as political ammunition by other people, above all by Vladimir Putin, and others close to the Kremlin. At the very height of the military action in Dagestan last summer, Yeltsin fired Prime Minister Stepashin and replaced him with Putin. Moreover, the President publicly named Putin his “heir for the year 2000″—an announcement which at the time provoked only laughter. And indeed, it seemed ridiculous. First, how was it possible that the current president could “appoint” the future president—are we living in Haiti or some such place?

Second: Putin, a man with a professionally nondescript face, previously the director of the FSB (the KGB’s successor organization), was virtually unknown to the public at large. It seemed that he had absolutely no chance of winning in a campaign against such experienced politicians as Evgeny Primakov, the former prime minister, Yury Luzhkov, the mayor of Moscow, or Gennady Zyuganov, the leader of the Russian Communist Party. Third: after the financial crisis of August 1998, Yeltsin’s own reputation was such that his public support of any candidate seemed to mean disaster for the person he backed.

Advertisement

Putin, however, was not fazed. Without missing a beat, he confirmed that he did indeed intend to run for president, but that at the moment the most important thing was the war in Dagestan. This impressed the public—and, in fact, seemed a correct judgment: Could there be anything more important for the government than military action on its own territory?

After the Chechen forces left Dagestan and returned to Chechnya in August, Putin announced that the current state of affairs in Chechnya could no longer be tolerated—which was true. The government could not stop now, he said; it had to strike at the Chechens’ bases, “even,” he said, “if they are on the territory of Chechnya.” (This logic is understandable, too—but leaves unmentioned a basic problem: How do you distinguish a “terrorist base” from a normal Chechen village?)

Putin began to send troops to the borders of the Chechen Republic. Many people took his words and actions as merely a demonstration of military power for the benefit of Maskhadov and the other official Chechen leaders, a move meant to force them to turn, at last, from mere verbal condemnation of the Islamic extremists to active measures against them. For attentive observers, however, his motives were obvious: the new prime minister had no intention of limiting himself to threats. He never even tried to initiate contacts with the legitimate government of Chechnya. He didn’t consider it necessary to present Maskhadov with an ultimatum. He wanted war, and it was clear why he wanted it.

The parliamentary elections were coming up in three and a half months—a dress rehearsal for the presidential elections of June 2000. It was quite likely that the movement called “Fatherland—All Russia” (consisting largely of former Soviet business managers and strong regional bosses), which opposed Yeltsin and the Kremlin establishment, would bring off a significant victory in these elections. And the newly anointed presidential candidate would be competing with the leaders of this movement, the most popular politicians in the country: Yury Luzhkov and Evgeny Primakov.

The only way Putin could manage a political victory over his Moscow competitors was to achieve a military triumph. And Dagestan was not enough. But would public opinion support renewed military action in the Caucasus? After all, only three years had passed since the Russian public expressed relief when the Khasavyurt agreement of 1996 was signed. True, since then the Chechens had done much to undermine any sympathy the Russians might have had for them. However, even the armed incursion into Dagestan had not sufficiently strengthened the anti-Chechen mood in Russian society for it to approve a new military venture. As recently as the end of August the prospects for popular support of a new campaign in Chechnya seemed more than doubtful.

Putin moved cautiously. He announced that the government was talking about nothing more than sealing the border with Chechnya. (He was lying, of course; only two weeks later a large-scale invasion began—and operations such as this cannot be planned in two weeks.) Then he said that in order to guarantee the troops’ safety they would have to occupy a few, just a few, hilltops on Chechen territory. Of course, it went without saying that no one was really talking about a war, God forbid; the government was only trying to ensure the safety of the neighboring regions.

And then, in September, explosions tore through Moscow and Volgodonsk—nighttime explosions in apartment buildings that killed well over two hundred people.

Those explosions were a crucial moment in the unfolding of our current history. After the first shock passed, it turned out that we were living in an entirely different country, in which almost no one dared talk about a peaceful, political resolution of the crisis with Chechnya. How, it was asked, can you negotiate with people who murder children at night in their beds? War and only war is the solution! What we want—so went the rhetoric of many politicians, including Vladimir Putin—is the merciless extermination of the “adversary” wherever he may be, whatever the casualties, no matter how many unarmed civilians die in the process, no matter how many Russian soldiers must give up their lives for a military victory—just as long as we destroy the “wasp’s nest of terrorists” once and for all. And it doesn’t matter in the least who this “adversary” is—the fighters Basayev or Khattab, the elite guard of President Maskhadov (who had nothing to do with the raid into Dagestan, or, of course, with blowing up apartment buildings in Russian towns), or simply a member of a local militia who is defending his native villagers from Russian troops that suddenly swoop down on them.

Russian politicians began to use a new language—the argot of the criminal world. The recently appointed prime minister was the first to legitimate this new language by publicly announcing that we would “bury them in their own crap.” It was after saying this that Putin’s rating in the polls began to rise astronomically: finally there was a “tough guy” at the wheel.

Old terms took on a completely new meaning. Thus, the word “terrorist” quickly ceased to mean someone belonging to a criminal underground group whose goal was political murder. Now the word came to mean “an armed Chechen”—anywhere. Military reports from Chechnya put it plainly: “A group of three thousand terrorists has been surrounded in Gudermes”; “two and a half thousand terrorists were liquidated in Shali.” And the war itself came to be called nothing less than the “antiterrorist special operation of the Russian troops.”

In Moscow this autumn a huge roundup of people from the Caucasus region took place and the harassment continues today; there was talk of setting up “temporary holding points” in the Moscow suburbs “for individuals living in the capital without appropriate documentation”—i.e., for people from the Caucasus who don’t have enough money to buy off the police. It seems that these “temporary holding points,” or, to put it more simply, internment camps, were not set up after all—though the intention to do so was telling. But apart from a handful of human rights activists, no one was shocked by these barbaric ideas.

The position of human rights activists themselves changed and the name acquired a new meaning. Today, human rights workers and organizations are considered the country’s primary internal enemies, a “fifth column” that is supported by Western foundations (read: secret services), and is conducting subversive activities against Russia. A series of articles on this theme was published not by some nationalist-patriotic yellow rag, but by none other than one of the preeminent newspapers of Russia’s free press—Nezavisimaya Gazeta.

It turns out that it is the human rights activists and the “unpatriotic” press who are guilty of bringing about the defeat of the Russian army in the last Chechen war: their reports created sympathy for the sufferings of the Chechen people and thus confused public opinion. No one, by the way, accuses either human rights activists or the press of having circulated false or one-sided information. In effect, they are accused of objectively reporting on events.

The generals have established an unprecedented information blockade around Chechnya. Some accounts have seeped through of horrors committed by Russian troops—such as the killing of civilians—that have been taking place in the military conflict zone and the “liberated territories.” These reports need systematic and independent investigation and I cannot specifically confirm them; but unfortunately I have no reason to disbelieve them either. Strictly speaking, the generals didn’t have to establish any information blackout. On those occasions when reports of destruction and casualties among the peaceful inhabitants of besieged Grozny do make it to the television screen, they no longer provoke revulsion in the Russian viewer.

2.

The current state of mind in Russia may be summed up in two words: “war hysteria.” And, of course, the apartment-building explosions were not the only factor causing it. Apparently, even before the recent violence began, public opinion in Russia was psychologically prepared to support tough government measures, regardless of what they were or against whom they were directed. What has happened is what was predicted some time ago: society is nostalgic for the “firm hand.”

In my 1997 article, I wrote that Chechnya’s military victory, which gave the country de facto independence, might in fact lead to the death of Chechen freedom. But I also wrote that Russia’s military defeat could turn out to be a blessing in disguise, that it might give new impetus to the effort to carry out reforms that had become gridlocked, that it might turn the country once again toward democracy and freedom. With regard to Chechnya my fears were justified; with regard to Russia, my hopes did not come true.

It wasn’t only the Russian economy that was damaged by the catastrophic financial crisis of 1998. To an even greater degree the political scandals accompanying the crisis undermined the population’s faith in the possibility and desirability of political democracy and social freedom in Russia. For many people the economic and political failure of “Yeltsin’s reforms” meant disillusionment with the ideals of “Western-style” liberalism—after all, for many years the public had been assured that reforms were being carried out according to the Western model.

The first symptom of the shift in society’s mood was the outburst of anti-Western emotion during the Balkan crisis. This had nothing whatever to do with “Slavic” or “Orthodox Christian” solidarity with the Serbs, or, moreover, with NATO’s violation of international law. The issue was something different. Russians fell definitively out of love with the object of their sudden, deep infatuation of about ten years ago: the West and everything associated with it, including the concepts of democracy, freedom, and human rights.

It is bizarre that in Russia many people see “Western intrigue” in the current mess in the Caucasus, failing to note the absurdity of the assumption that the Western nations, in particular the United States, would support their sworn enemies—Islamic terrorists—against Russia. European and American denunciations of the cruelties of the current war are seen as further confirmation of the West’s “anti-Russian feelings.” The Western protests are not credited with any sincerity.

But the Russian public’s negative emotions have been directed for the most part against the current state of affairs in Russia itself, which has been quite correctly identified with the political machinations of the Yeltsin era and—absolutely incorrectly—with the values of liberal democracy.

One might have expected that this situation would end with the restoration of the ancien régime, as conceived by Zyuganov, or with a semi-restoration as conceived by Primakov. It’s quite likely that such fears led the Kremlin (and, perhaps people outside the Kremlin) to consider a plan to bring about an “authoritarian modernization” of the crippled Yeltsin regime. I am almost certain that the final version of this plan had been drafted by mid-summer. The key factor was, of course, not the plan itself but the state of mind that made it workable. It could be summed up in the following formula: “We don’t want to return to communism, but we’re fed up with your democracy, your freedom, your human rights. What we want is order.”

And the directors of the drama being written had already, it seems, chosen an actor to play the leading role. It didn’t matter that he quite obviously would never be compared to Napoleon or Cromwell—whether in administrative and political talents, or even in toughness. The overwrought Russian public was quite prepared to accept as evidence of toughness some hysterically aggressive remarks on television and some views of Grozny destroyed by bombs and artillery.

Testifying to that acceptance by the public is the astonishing breakthrough that the movement called “Unity”—quickly put together “to support the prime minister”—made in the December parliamentary elections. The Unity bloc, also known as “The Bear,” gained 23 percent of the vote.2 For a political bloc that didn’t even exist at the end of the summer, that entered the elections without any political, economic, or social program, with essentially a single slogan, “We support Putin,” and whose leaders were unknown in Russia, that result was not simply a good showing but an overwhelming success.

After the election it was time to perform the last act of the play. I am almost certain that Yeltsin’s dramatic resignation on December 31, 1999, was part of the plan I mentioned earlier. And the issue here is not simply that Yeltsin’s resignation pushed Putin’s competitors into a foreshortened political campaign, giving him the opportunity to make maximum use of his current popularity before the early March elections. It was also a demonstrative gesture, comprehensible to the masses: the new leader was now rid of the stigma of being a “Yeltsinite,” which would have been almost inevitable if he had entered the presidential race as Yeltsin’s prime minister. Now he can appear before the electorate free of the sins of the previous political regime, which has been unpopular for many years and which destroyed itself after August 1998.

In the mind of the masses the “young, decisive politician” now stands in contrast to the elderly Primakov and the retrograde Zyuganov, as well as to his feeble predecessor. The public is being gradually but persistently encouraged to see Putin’s presidency as an alternative both to a Communist restoration and the incompetence of “the democrats.” (Of course, the Yeltsin regime of the last few years could only be considered democratic by a large stretch of the imagination—but most Russian voters associate the “democrats” with Yeltsin.)

This seems to mean that the Chechen campaign will continue at least until March, when Vladimir Putin will almost certainly become the second president of Russia. Before the war he didn’t have the slightest chance of being elected.

I do not claim that Putin deliberately organized the September explosions in order to have an excuse to begin the war. The story of the explosions is very murky; but I have no reason to believe, as some do in Russia and the West, that the explosions were the work of the Russian secret service. Frankly, I think Western commentators are inclined to exaggerate both the power and, more important, the professionalism of the KGB and its successors. I have had dealings with this organization for many decades; in my view they don’t have people who are sufficiently qualified and decisive to carry out such an action.

Nevertheless, it’s true that the world of terrorism and the world of the secret services are not divided by a wall so impassable that they are prevented from merging into one landscape. And a police provocation can take different forms: for instance, the police may fail to act when they receive threatening information—if, that is, someone thinks that inaction more closely corresponds to the unspoken desires of the higher-ups.

The presumption of innocence naturally applies not only to Chechens but to the secret service. In fact, now, after three and a half months, more and more people recognize that the “Chechen terrorist” version of these crimes has not been confirmed by any facts at all. At least, no evidence, either direct or indirect, has yet been presented to the public to support the claim that the terrorists are to be found on “the Chechen trail.” What little is known about the people suspected of having some responsibility for the explosions indicates that this is likely a false trail: the individuals in question are not even ethnic Chechens.

But the absence of evidence doesn’t prevent the population from continuing to enthusiastically support the government’s actions in the Caucasus. The explosions were needed only as an initial excuse for these actions.

While I do not believe Putin himself created this excuse, I have no doubt that he cynically and shamelessly used it, just as I have no doubt that the war was planned in advance. And not only in the headquarters of the Russian army, but, as I have suggested, in some political headquarters as well.

Which political headquarters? It is a question that is unpleasant even to contemplate. These plans do not bear the stamp of the older generation of Communists or the fanatic younger supporters of Great Russian Statehood, whose reactionary influence on the life of the country I so feared at one time. Instead, they are in keeping with the bold, dynamic, and deeply cynical style of a new political generation. It is unlikely that, after next March, President Putin will either resurrect Soviet power or resuscitate the archaic myths of Russian statehood. More likely he will build a regime which has a long tradition in Western history but is utterly new in Russia: an authoritarian-police regime that will preserve the formal characteristics of democracy, and will most likely try to carry out reforms leading to a market economy. This regime may be outspokenly anti-Communist, but it’s not inconceivable that the Communists will be tolerated, as long as they don’t “interfere.” However, life will not be sweet for Russia’s fledgling civil society.

The so-called rightists (i.e., the “Union of Right Forces,”3 which includes my own party, the “Democratic Choice of Russia”), had in effect announced their support of Putin’s candidacy in the presidential elections before Yeltsin resigned. Indeed, the fact that the Union of Right Forces passed the 5-percent barrier4 in the parliamentary elections, an accomplishment which was more than doubtful just a couple of months ago, is largely owing to the fact that a number of its prominent leaders, including such reformers as Anatoly Chubais and Sergei Kiriyenko, publicly supported Putin and the war.

Putin, in turn, doesn’t conceal his sympathy for the rightists, his interest in their economic program, and particularly his desire to have Anatoly Chubais work on his coming election campaign. (Chubais is widely credited with much of the success of Yeltsin’s 1996 campaign.) And this is understandable—you can’t go shopping for an economic program in the ranks of Unity, which was created by the government solely to get its own hand-picked, controllable deputies into the Duma. Nor, certainly, can you do so among the Communists.

For this reason a deal between Putin and the rightists seems highly likely. Putin’s administration will accept the liberal program of economic reform that the rightists insist on. The rightists will refrain from excessive criticism of the authoritarian and police features of Putin’s government. And perhaps they will even support more stringent police measures, as they have already supported the second Chechen war. There is nothing new under the sun. Something similar happened in Chile during Pinochet’s dictatorship.

Such, in my view, are the political prospects. As for the war in Chechnya, which has been central to the recent political strategy, a military victory there is possible and even likely. It seems clear that the military command has firmly resolved not to worry about casualties among unarmed civilians; they are capable of wiping out any part of Chechnya, including Grozny, in order to destroy “terrorists.” The result of this victory will in all likelihood be a drawn-out, vicious guerrilla war in the mountains and in the foothill regions. As is well known, moreover, there is only one way to destroy guerrillas: to make no distinctions between them and the unarmed people among whom they hide. In other words, a campaign of ethnic genocide must be carried out in the regions controlled by the guerrilla movement.

The Russian army is quite prepared for genocide. This was demonstrated in the previous war; it was proven again recently by events in the village of Alkhan-Yurt, where professional soldiers shot around forty unarmed inhabitants—for no reason. It has already been confirmed by official announcements that vacuum bombs are being employed in Chechnya—terrible weapons that kill every living thing over a wide area, including people hiding in shelters.

What is new this time around is that Russian society as a whole is prepared to carry out genocide. Cruelty and violence are no longer rejected. But is Russia ready for a protracted terrorist campaign in its own towns and cities? I have no doubt that if even a few thousand Chechens are left alive somewhere after this war, there will be such a terrorist campaign, and that it will go on for a long time.

In my article of two and a half years ago I wrote that the visions of catastrophe evoked by government propaganda in order to justify the war in Chechnya—including violence and the advent of Islamic extremism—in fact materialized after the war, and as the direct result of the war. Today the Russian public is being frightened with the specter of Chechen terrorism. What phantom will materialize as a result of these new incantations? Unfortunately, the answer, in my view, is all too predictable. It is also clear that, given our traditions, such developments will make the prospects of a victory of democracy in Russia improbable any time soon.

Instead, I fear, it is very likely that the year 2000 will someday be re-ferred to as the “twilight of Russian freedom.”

—January 13, 2000

—Translated from the Russian by Jamey Gambrell

This Issue

February 10, 2000

-

1

See my “Russia After Chechnya,” The New York Review, July 17, 1997. ↩

-

2

The interregional movement Unity was established in September 1999. Formally, Vladimir Putin does not belong to this or any other party or bloc. Unity’s official leaders are Sergei Shoigu (the minister of emergency situations), Alexander Karelin (a world champion wrestler), and Alexander Gurov (a retired police major general). The party list consists largely of nationally unknown athletes, minor regional bureaucrats, and interior ministry officers. The bloc did not publish any program. ↩

-

3

The Union of Right Forces is a coalition of democratic and reform-oriented parties and movements. It was founded in November 1998 (and originally called “For the Right Cause”) on the basis of “Democratic Choice of Russia” (to which the author of this article be-longs and which is known as “Gai-dar’s party”). Other parties in the bloc include Sergei Kiriyenko’s “New Strength”; Boris Nemtsov’s “Young Russia”; Irina Khakamada’s “Common Cause”; “Democratic Russia”; Samara governor Konstantin Titoz’s “Voice of Russia,” Konstantin Borovoz’s “Party of Economic Freedom”; Vladimir Lysenko’s “Republican Party”; and a number of other small groups. The formal leaders of the Union of Right Forces are Kiriyenko, Nemtsov, and Khakamada. Anatoly Chubais ran the bloc’s election campaign. The bloc unexpectedly received 8.5 percent of the vote in the December elections, surpassing its traditional democratic rival, Grigory Yavlinsky’s “Yabloko.” The Union of Right Forces had no relationship with Unity other than its support of the government. ↩

-

4

The Russian Duma has 450 seats. Half of them are representatives elected directly in so-called single-mandate districts; the other half are drawn from party lists. The 225 party seats are distributed proportionally among those parties that receive more than 5 percent of the overall vote. ↩