This stonewalling strategy works. Judge Samuel Alito’s performance was particularly evasive, but his lack of candor made his confirmation inevitable. If he had revealed the opinions he actually holds about what rights the Constitution protects, he might well have been defeated. But he provided no headlines that would alert Americans to the very real danger that he will join the legal revolution that right-wing administrations, think tanks, judges, and justices have been planning for decades.

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his own hearings last fall, offered little more substance than Alito has; he apparently persuaded the several Democratic senators who voted for him that he would prove to be a moderate rather than a right-wing justice.1 But in his first important vote he joined the two ultra-conservative justices, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, in dissenting from the Court’s 6–3 holding that former Attorney General John Ashcroft had no authority to stop Oregon voters from adopting a cautious assisted-suicide plan.2 It seems likely that Alito will now provide a dependable fourth vote to form a right-wing bloc that will have a great impact on constitutional law for a very long time. But his performance before the Senate, like Roberts’s, gave the public no warning of this and therefore no chance to object. Democratic senators appear likely to vote solidly against Alito because they think they know what he actually stands for. But the result of his steadfast silence means that they have little chance of creating popular support for a filibuster to defeat him.

In my view, future nominees can be discouraged from such evasion only if there is a change in the public’s understanding of the function of the confirmation hearings and of the nominees’ moral responsibilities in those hearings. Enough people must be persuaded that the hearings are not a game of hide-and-seek and that a nominee who fails to be candid is morally culpable. It would be helpful to that end if the chairman of the Senate committee (or the ranking member of the other party) were to explain in his opening statement that the committee accepts without further reassurance that the nominee intends to abide by the law and will apply what he believes to be the general principles that underlie the Constitution rather than try to invent new ones.

He should then add that he and the committee are well aware that lawyers disagree about what these principles are, and how they should be identified, and that the committee is therefore anxious to know the nominee’s answers to these controversial questions of principle. Perhaps the public can somehow be persuaded that a nominee’s failure to answer those substantive questions candidly would justify—indeed force—senators of both parties to vote against his confirmation. That may sound unlikely, but it is hard to see what else could save the constitutional process from irrelevance.

Many lawyers think that the change I propose would be a change for the worse.3 Constitutional rights are often unpopular, and we should want Supreme Court justices who will protect those rights even when a substantial majority of the public is opposed to them. Any requirement that nominees disclose their actual opinions might mean that only judges with a particularly narrow view of individual rights would be appointed. In today’s political climate, for example, presidents might be reluctant to nominate judges who would assert strong liberal opinions about the barrier between church and state. That objection would be stronger, however, if presidents appointed justices on intellectual ability alone, and were as ignorant as the public generally is about their nominees’ constitutional philosophy. But of course they do not and are not.

Harriet Miers, whom Bush had first nominated for the seat that Judge Alito will now hold, had to withdraw her nomination because right-wing Republicans, though they represent only a minority opinion on such matters as abortion and presidential power, are nevertheless sufficiently powerful within Bush’s political base to dictate that he choose someone in whom they had more confidence. The conservatives who condemned Miers were ecstatic about Alito. The current ground rules guarantee not that judges will keep their own counsel on constitutional matters until they are on the Court, but that the President and the politicians he is most anxious to please will know his views while the nation does not. Alito was interviewed before his nomination not only by President Bush and administration lawyers but by Vice President Cheney, his deputy, “Scooter” Libby, who has since been indicted, and by Karl Rove. Do you doubt that they know something about Alito’s views of the president’s powers and other politically sensitive matters that he did not disclose at the hearings?

The Senate’s decision to reject the nomination of Robert Bork in 1987, after he had candidly announced his very narrow view of constitutional rights, showed that large numbers of Americans are attracted in principle to the idea of substantial constitutional rights, even when they disagree about which particular rights people should have. There would, in any case, be little point in the constitutional requirement that the Senate “consent” to judicial nominations if the Senate’s duty were merely a matter of ascertaining that the nominee does not take bribes and is willing to proclaim allegiance to the rule of law.

Advertisement

2.

In 1985, in his application for a job with the Reagan administration, Judge Alito wrote that he had always been a conservative, and that his career as a lawyer in that administration justified his claim.4 His subsequent fifteen-year record as a federal judge confirms it as well: his decisions place him far to the right even among other federal judges who were appointed by Republican presidents. Statistics about judicial opinions must be treated with great care, since a judge’s decision in any particular case may turn on facts and doctrinal subtleties that are hard to fit into neat categories. Still, the statistics in Alito’s case are revealing. Professor Cass Sunstein, a respected and cautious legal scholar, has analyzed all of Alito’s dissenting opinions in cases that might plausibly be thought to raise issues about individual rights against what Sunstein calls “established institutions.”5 He reports that Alito voted against individual rights in 84 percent of the cases in which a majority of other judges on his court upheld those rights. In only two of these cases was the majority composed only of judges appointed by Democrats. Indeed, in almost half of the cases the majorities from which Alito dissented were made up entirely of Republican appointees to the court.

Sunstein made a parallel study of the dissents of the Republican appellate judges widely thought to be very conservative—including Michael Luttig and Harvie Wilkinson, who were widely regarded as candidates for the nomination Alito received. Sunstein classified the dissents of between 65 percent and 75 percent of these judges as “from the right”; he classified 90 percent of Alito’s dissents that way.

The Washington Post also compared Alito’s record with that of other Republican-appointed federal judges. It compared his votes on different issues in divided-vote cases—those in which judges on the panel disagreed—with those of a national sample of judges appointed by Republicans.6 It reported that Alito voted with the prosecution in 90 percent of the criminal law cases, with the government in 86 percent of the immigration cases, and against the claimant in 78 percent of cases involving discrimination on grounds of race, age, sex, or disability. By contrast, the sample of Republican-appointed judges voted for the prosecution in 65 percent of the criminal law cases, for the government in 40 percent of the immigration cases, and against the claimant in 52 percent of the discrimination cases.

Alito’s written opinions, several of which were discussed in some detail in the hearings, seem to confirm the ideological convictions that these statistics suggest. His dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Pennsylvania case in which the Supreme Court later reaffirmed its earlier Roe v. Wade protection of abortion rights, was of course of particular concern. Alone on the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, he voted to uphold a provision of the Pennsylvania law that required married women to inform their husbands before seeking an abortion, except women who could prove that their husbands were not the father of the child or that they would be subject to physical abuse if they told their husbands.

The other Third Circuit judges worried that some pregnant women would not want publicly to charge their husbands with violence or feared abuse that was not only physical. Alito insisted that this did not matter for two main reasons. First, he wrote, most women who had abortions were unmarried anyway; and second, since a state could require teenage women to inform their parents before an abortion, it could, by “analogy,” require an adult woman to inform her husband. These are very bad arguments, and were soon seen as such. As Justice O’Connor said in her Supreme Court opinion in the case, a state cannot be excused for violating even a few people’s constitutional rights, and adult women should not be treated as children. But those positions might very well appeal to a judge who believes, as Alito declared he did in a 1985 Justice Department memorandum, that the Constitution contains no right to abortion and that the Supreme Court’s mistake in recognizing that right should be corrected gradually by seizing opportunities to cut back the protection it offers.

In his Senate hearings Alito tried to distance himself from these earlier claims without disclosing whether they still reflected his opinion. He said that Roe v. Wade is a precedent that deserves respect though he refused to say that a right to abortion is “settled law.” He was equally cagey about his past statements on what might turn out to be an even more important constitutional issue: the president’s claimed power to ignore congressional statutes in conducting what he considers military operations. A number of senators were particularly worried by Alito’s speech to the ultra-conservative Federalist Society in 2000 when he was a sitting judge, in which he said that

Advertisement

when I was in [the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel]…we were strong proponents of the theory of the unitary executive, that all federal executive power is vested by the Constitution in the president. And I thought then, and I still think, that this theory best captures the meaning of the Constitution’s text and structure…. The case for a unitary executive seems, if anything, stronger today than it was in the 18th Century.

The phrase “unitary executive” has been much used by conservatives anxious to increase the president’s power, particularly in the “war on terrorism.” Justice Thomas, for example, appealed to the doctrine to justify his dissent from the Court’s refusal, in the Hamdi case, to allow the president unrestricted discretion to hold prisoners indefinitely as enemy combatants. John Yoo, then a Justice Department attorney, who has been widely described as the author of the administration’s torture policy,7 wrote after September 11 that

the centralization of authority in the president alone is particularly crucial in matters of national defense, war, and foreign policy, where a unitary executive can evaluate threats, consider policy choices, and mobilize national resources with a speed and energy that is far superior to any other branch.

The then assistant attorney general, Jay Bybee, advised his superiors in 2002 that

even if an interrogation method arguably were to violate [an anti-torture law], the statute would be unconstitutional if it impermissibly encroached on the president’s constitutional power to conduct a military campaign.

Bush has himself mentioned the “unitary executive” doctrine 103 times in the “signing statements” he has issued when signing bills in order to make it plain that he does not regard himself as bound by congressional restrictions; he was appealing to that doctrine when he declared, before signing a bill including the McCain Amendment banning torture and inhumane treatment of prisoners, that he would “construe” the act “in a manner consistent with the constitutional authority of the President to supervise the unitary executive branch and as Commander in Chief….”

Alito told the senators that the unitary executive doctrine he meant to endorse in 2000 was different from the doctrine cited in Bush’s statements because, in his view, “the question of the unitary executive…does not concern the scope of executive powers, it concerns who controls whatever power the executive has.” He meant to suggest, he said, no more than that it is the president rather than any other executive official who controls the executive branch, not that Congress lacks the capacity to restrict the power of all executive officials including the president. But that reading is inconsistent with other statements he has made. In a 1989 speech to the Federalist Society, for example, he called Scalia’s dissent in the Supreme Court’s 1988 Morrison decision “brilliant.”8

In that case, the Court upheld the Independent Counsel Act, which limited the president’s ability to fire an independent counsel appointed to investigate possible crimes in the executive branch. Scalia dissented on the broadest possible ground: he said that the statute must be struck down

on fundamental separation-of-powers principles if the following two questions are answered affirmatively: (1) Is the conduct of a criminal prosecution (and of an investigation to decide whether to prosecute) the exercise of purely executive power? (2) Does the statute deprive the President of the United States of exclusive control over the exercise of that power?

If Scalia were right, then Bush would also be right in saying he could approve torture: since the day-to-day conduct of war is the exercise of purely executive power, Congress could not then forbid the president to torture prisoners if he believed that torture was militarily wise.

Bush’s claims that he is constitutionally free to ignore congressional statutes, both in his treatment of prisoners and in his decisions to wiretap Americans without any form of judicial oversight,9 threaten a genuine constitutional crisis that can only be resolved by the Supreme Court. It is therefore disturbing that four justices who will now be serving on the Court—Roberts, Alito, Scalia, and Thomas—have expressed strong support for such an expanded view of presidential power.10 In response to questions by Senator Russell Feingold, Judge Alito made a particularly disquieting suggestion. He said that the question of how far Congress can control the president might fall under the “political question” doctrine: the doctrine, as he described it, that the Supreme Court should not intervene in disputes that should be resolved between the other two branches of government. But if the Court appeals to that doctrine and refuses to declare that the president has no right to disregard legislation, then it hands victory to the president because Congress has no way of checking the president without judicial enforcement.

3.

Judge Alito duly assured the Judiciary Committee that if confirmed he would enforce the law, not his own “personal bias.” It is true, he said, that facts change—the framers of the Fourth Amendment, which condemns “unreasonable” searches and seizures, could not have anticipated sophisticated electronic eavesdropping devices. But the underlying “general principles” remain the same and the judiciary “must apply the principles that are in the Constitution” and not “inject its own views into the matter.”

The crucial question, of course, which these pious statements leave entirely unanswered, is how judges should decide what the principles are in the Constitution. The key clauses, including those separating the powers of the different branches of government as well as those creating individual rights like the due process and equal protection clauses, are very abstract. American lawyers have always disagreed, and continue to disagree, over what principles these clauses contain. If Judge Alito had been even minimally candid he would have conceded what every law student knows: that judges cannot avoid drawing on their own understanding of fundamental principles of decent government when they interpret those abstract clauses. But that is what he denied.

He did confirm that he believes—as any successful nominee must say he does—that the right to use contraceptives is part of the “liberty” protected by the due process clause and the right against segregation is part of the “equality” guaranteed by the equal protection clause. Senator Richard Durbin observed that neither of these rights is explicit in the text of those clauses, and asked Judge Alito which interpretative strategies he had used to find them there so that the senators might judge what else those strategies might find or not find in the Constitution.

Alito’s response was not impressive. He said that racial segregation plainly denies equality because it treats blacks and whites differently. But every statute inevitably treats some people differently from others, while not every statute violates the equal protection clause. He said even less about contraception: only that the Supreme Court had decided that contraception falls within the area of liberty protected by the due process clause, which does not explain why he thinks the Court was right to find it there.

Alito had publicly declared, in 1988, that Judge Robert Bork was “one of the most outstanding [Supreme Court] nominees of this century.” That statement seemed to reveal something of Alito’s constitutional philosophy, because Bork’s understanding of the crucial abstract clauses of the Constitution was so constricted that his nomination to the Court was decisively rejected. But when Senator Herb Kohl reminded Alito of this statement, he said that in fact he disagreed with many of Bork’s views and that he had praised Bork only out of loyalty to the Reagan administration, which had nominated him. That is not believable: loyalty may require a Justice Department lawyer not to speak out against a nominee whose views he thinks are wrong, or even to support the nomination; but it hardly requires him to describe the nominee as one of the greatest of the century. Once again, however, Alito succeeded in giving his opponents nothing they might use to arouse public concern about his nomination.

He did, however, make one comment of considerable—and alarming—significance. When Senator Charles Grassley asked him how he would interpret the text of the Constitution’s abstract clauses without allowing “personal bias” to intervene, he said that “you would look to the text of the Constitution and you would look to anything that would shed light on the way in which the provision would have been understood by people reading it at the time.” This is a frank endorsement of the “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution that Bork used to defend the extreme conservative views that Alito now says he rejects. It is precisely the strategy that Judge Roberts in his hearings rejected as inappropriate. Roberts said that since the Constitution’s framers use abstract moral language it is the job of contemporary judges to answer the moral questions that language raises rather than to discover how the framers themselves would have answered those questions.11

Judge Alito not only embraced the originalist strategy of interpretation that Roberts rejected, but embraced it in the distinctive form that Justice Scalia has often proposed: whereas other conservatives have appealed to the intentions of the framers, Scalia has appealed instead to the expectations of the framers’ contemporaries.12 No wonder Senator John Cornyn of Texas, an enthusiastic Republican supporter of the nominee, referred to him, accidentally, as “Judge Scalito.”

Alito’s response provides a formula for a highly conservative constitutional jurisprudence, one that would support few of the individual rights that the Supreme Court has found in the due process and equal protection clauses, including a right to abortion. That jurisprudence would not support even the rulings that Alito says he accepts. The Americans who read the Fourteenth Amendment when it was enacted after the Civil War would certainly not have thought that it contained any principle prohibiting laws against contraception or banning the racially segregated schools with which they were familiar. Alito did say repeatedly that he would respect, as precedents, even those past Supreme Court decisions with which he disagreed. But that apparent concession is less important than it might have seemed, for two important reasons.

First, judges vary widely in their opinions about what any particular past decision is precedent for. Is the Griswold decision about contraception precedent only for the proposition that states may not forbid the use of contraceptives? Or is it precedent for the broader principle that the Constitution grants a general right to privacy in matters of sexual preference and practice? Does the doctrine of precedent require respect only for the narrow holding in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey: that states may not restrict abortion in the particular ways that the Court rejected in those cases? Or does the doctrine require respect for the very broad proposition that Justices Kennedy, O’Connor, and Souter set out in their joint opinion in Casey: that Americans have, in principle, a constitutional right to develop their personal convictions about how and why human life has intrinsic value and how that value is best realized?

Whether Judge Alito reads precedent in a narrow or a broad way matters crucially for any estimate of how far his declared respect for precedent will in fact moderate his conservative political convictions. His discussion of how the Morrison decision bears on questions of presidential power suggests a very narrow view of the scope of precedent. Morrison, he told the senators, “is a precedent of the court…. It concerns the Independent Counsel Act, which no longer is in force.” Most lawyers would think that Morrison is concerned with a great deal more than that.

Moreover, as Alito also said repeatedly, the doctrine of precedent is not “inexorable.” He expressly reserved the right to vote to overrule Roe v. Wade if he were to decide that he had adequate reason to do so. It might be sufficient reason to overrule Roe, he said, simply if the decision was seriously mistaken. After all, the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which allowed racial segregation, was taken as law for much longer than Roe has been and was also reaffirmed countless times. We all agree, Alito said, that the Court was right to overrule it in 1954—in the Brown v. Board of Education case—just because Plessy so plainly misread the Constitution.

Judge Roberts, in his hearings, set out a different and equally threatening ground for ignoring even a longstanding Supreme Court precedent that has been repeatedly affirmed: its doctrinal basis, he said, may have been eroded by later decisions which, though they respected the narrow holding of the original decision, are nevertheless inconsistent with any principled rationale for it.13 That is exactly the strategy Alito recommended in his 1985 memo. “What can be made,” he asked, “of this opportunity to advance the goals of bringing about the eventual overruling of Roe v. Wade and, in the meantime, of mitigating its effects?” His answer was that the government should take every available opportunity to regulate abortion without contradicting the explicit narrow holdings of Roe or of the cases that upheld and expanded on it.

When Judge Alito is confirmed, the four justices we may expect to form an ideologically conservative phalanx—Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito—will be in a position to execute that strategy. They may begin with Gonzales v. Carhart, a case the Court has been asked to consider that, if it does consider it, will provide it with an opportunity to overrule its earlier decision that a statute prohibiting “partial birth” abortion must contain an exception to protect a mother’s health. That case was decided 5–4 in 2000, with Justice O’Connor, whom Judge Alito replaces, as the deciding vote.14 Or they may let the question of abortion alone for a while and transfer their attention to diminishing the power of Congress, or expanding the power of the president, or cutting back on affirmative action, or limiting the newly expanded rights of homosexuals or some other minority.

It is dangerous to predict what the Supreme Court, or indeed any justice, will do, and I hope my fears will turn out to be exaggerated. Justice Anthony Kennedy now replaces Justice O’Connor as the swing vote, and several of his recent opinions are encouraging (for example, his argument that the federal government could not prohibit Oregon’s assisted suicide plan). But there seems little doubt that the Court will now move to the right. We may be on the edge of a new, long, and much darker era of our constitutional history.

—January 25, 2006

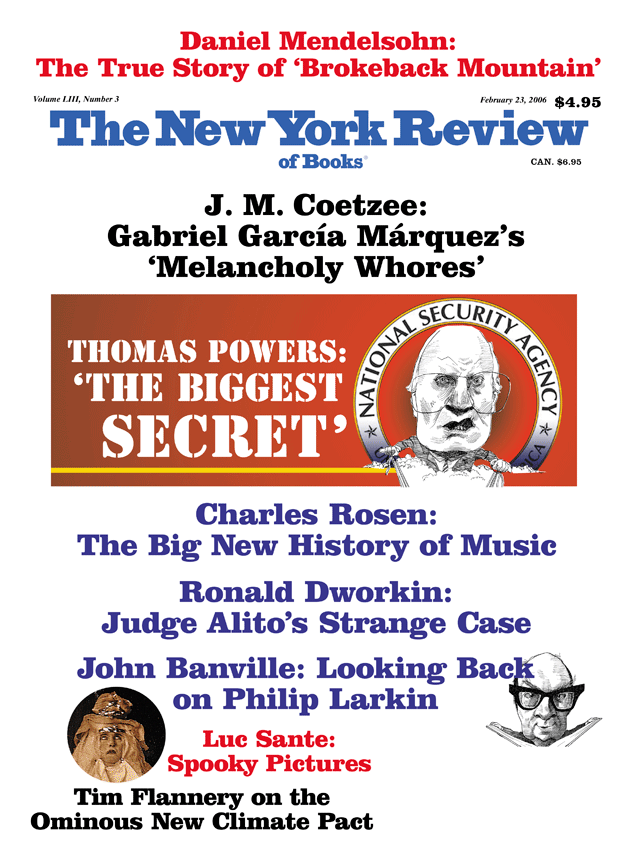

This Issue

February 23, 2006

-

1

See my article “Judge Roberts on Trial,” The New York Review, October 20, 2005. ↩

-

2

See Linda Greenhouse, “Justices Reject US Bid to Block Assisted Suicide,” The New York Times, January 18, 2006. ↩

-

3

Alito’s own argument for refusing to offer opinions about principles that might come into play in cases before the Court sounded like a parody: “It would be wrong for me to say to anybody who might be bringing any case before my court…, I’m not even going to listen to you; I’ve made up my mind on this issue; I’m not going read your brief; I’m not going to listen to your argument; I’m not going discuss the issue with my colleagues. Go away.” ↩

-

4

In his 1985 job application Alito said that he believed in the protection of “traditional values” and listed, among the organizations to which he belonged, the Concerned Alumni of Princeton, which was notorious for campaigning against admitting women and minority students to Princeton. While in the Justice Department he wrote memos declaring that the Constitution contains no right to abortion and that the attorney general should be immune from civil suits when he illegally wiretaps Americans. ↩

-

5

See “Letter from Professor Sunstein on Alito’s Dissents,” The New York Times, January 10, 2006; www.nytimes.com/2006/01/10/politics/politicsspecial1/sunstein-letter.html. ↩

-

6

See “Which Side Was He On,” The Washington Post, January 1, 2006. ↩

-

7

See David Cole, “What Bush Wants to Hear,” The New York Review, November 17, 2005. ↩

-

8

Morrison, Independent Counsel v. Olson Et Al., 487 U.S. 654 (1988). ↩

-

9

See the letter to members of Congress on NSA spying from fourteen former officials and constitutional scholars, The New York Review, February 9, 2006. ↩

-

10

Roberts joined a D.C. Circuit opinion affirming the president’s power to detain prisoners indefinitely. See my article “Judge Roberts on Trial.” ↩

-

11

See “Judge Roberts on Trial.” ↩

-

12

See Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation (Princeton University Press, 1997). ↩

-

13

See “Judge Roberts on Trial.” ↩

-

14

See Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 914 (2000). ↩