Mao’s Invisible Hand is one of those books that make one feel good about scholarship. It describes inner workings of Chinese Communist society about which few nonexperts know anything—it may even surprise the experts—and it will interest anyone professionally interested in China. Its central purpose is to explain how China has escaped the disintegration of other Communist states; but the contributors to the book do not cram their research into a template that promises more coherence than Chinese realities can provide.

The big idea advanced by Sebastian Heilmann of the University of Trier and Harvard’s Elizabeth J. Perry, both well- established scholars of Chinese politics, concerns the ability of the Chinese Communist regime to adapt. Many China-watchers, they recall, predicted that the People’s Republic would collapse after Tiananmen in 1989; nowadays some maintain that the spread of the market will inevitably lead to a civil society and even some form of democracy. From the regime’s point of view, such predictions may recall the warnings of Lenin, quoted by one of the contributors to this volume, who in 1902 urged that the Party must “struggle against spontaneity” because the spontaneous impulses of the masses can result “in the ideological enslavement of the workers by the bourgeoisie.”

In their first chapter, however, Perry and Heilmann contend that the post-Mao regime has “become increasingly adept at managing difficult challenges ranging from leadership succession and popular unrest to administrative reorganization, legal institutionalization, and even global economic integration.” Yet there is no implication anywhere in this book that the editors and their colleagues approve of the regime’s strategies; they are concerned to show how they evolved and actually work.

They state that the regime’s “staying power” is observable “up to this point” and has very dark sides: official corruption, the ruin of the environment, and no civil liberties. “Up to this point,” as is usual with volumes based on conferences, can mean some years ago. Right now is an even worse time for Chinese civil liberties, with the Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo behind bars, many of his supporters and human rights lawyers detained, and the arrest in 2011 and release eighty-one days later of the now largely silenced artist Ai Weiwei—to name only two of the nonviolent dissidents who have been subject to repression. Chen Guangcheng has made it to NYU but his wife and associates have been treated brutally.

The editors and contributors agree that Mao’s successors have retained, although in often-changed form,

a signature Maoist stamp that conceives of policy-making as a process of ceaseless change, tension management, continual experimentation, and ad-hoc adjustment.

The editors insist this has been a relatively recent development in governance that is understood neither by political science nor theories of modernization. China’s record poses a paradox for those convinced that deviations from the standard modern assumption about progress—that economic development will lead to more open societies—must fail. The Maoist strategy, the authors write, began during the thirty-year period starting in the early 1930s when the Party was driven out of the cities into the countryside and the Long March of 1934–1935 took place from south to north China, with guerrilla headquarters being established at Yan’an in 1936.

This meant surviving in some of China’s poorest hinterlands and relying on improvisation. The authors of Mao’s Invisible Hand argue that China’s post-Mao leaders, especially those like Deng Xiaoping whose memories reached back to the darkest days before the 1949 revolution, similarly used new ideas and techniques for purposes that Mao would have condemned, especially for reforming the economy, but that reflect his unpredictable and experimental approach.

Roderick MacFarquhar calls this “guerrilla-style policy-making,” a term used throughout the collection; that notion animated Mao throughout his career and long after the Communist victory in 1949. It could be disastrous, as with the Great Leap Forward of 1958–1961, which led to the worst famine in Chinese, if not human, history. But such an approach “proved highly effective when redirected to the economic modernization objectives of Mao’s successors.” The Maoist elements, which the book’s contributors underline, “encourage decentralized initiative within the framework of centralized political authority….”1

Central to understanding this sometimes disastrous, sometimes successful “guerrilla policy,” the editors emphasize, are its resilience and adaptability. Resilience means absorbing shocks when things go wrong; adaptability is the capacity to find ways of being what they call “proactive,” “reactive,” and “digestive,” together with the determination to try something new, thus making use of fresh challenges and opportunities. What Mao’s successors have always held in reserve is their power to crush those who stray from what Maoists call “the commanding heights” of priority and command.

Advertisement

The editors, and for the most part their contributors, do not duck the fact that many of the “grievous and growing social and spatial inequalities” attendant on guerrilla policymaking “would surely have undone less robust or flexible regimes.” They describe, too, vast upheavals like the hundreds of uprisings in the spring of 1989 that the leadership violently repressed. Decades earlier, as they dealt with civil war, Japanese occupation, and leadership divisions within the Party, “Mao and his colleagues had come to appreciate the advantages of agility over stability,” although, I would add, stability is exactly what they invariably claim to be preserving no matter what changes they make.

Mao’s closest comrades, including Deng and Hu Yaobang, absorbed the chairman’s “work style,” which the editors, brilliantly, in my opinion, sum up as marked by “secrecy, versatility, speed, and surprise”—in short, politics as warfare. The leaders carefully keep for themselves the power to make decisions about strategic policies and the overall direction of the economy; but they encourage much local initiative—unless it goes wrong or goes too far astray. In that case all alliances can be broken or newly reestablished. The guerrilla style means maximizing the leaders’ choices and initiatives “while minimizing or eliminating one’s opponents’ influence on the course of events.” In the face of most informed opinion at the time, including mine, this is what enabled Deng and his colleagues, as they dismissed in 1989 their high-ranking, long-term comrade Zhao Ziyang, not only to survive Tiananmen but to emerge tougher and more successful than ever, in part, as this book shows, by buying off some of their severest critics.

Perry and Heilmann characterize this style of policy as “fundamentally dictatorial, opportunistic, and merciless.” Scholars of modernization will have to consider, as a result of this book, what many may find discouraging, or even gloomy:

The adaptive capacity of China’s non-democratic political system offers a radical alternative to the bland governance models favored by many Western social scientists who seem to take the political stability and economic superiority of capitalist democracies for granted…. [These social scientists should take] a sober look at the foundations of innovative capacity displayed by non-democratic challengers such as China.

A capacity, the editors point out, that can also be damaging and dangerous for large parts of China’s population.

Tracing the origins of the Maoist experimental method, the contributors—astonishingly, at least to me—reach back to John Dewey, whom Mao heard lecture. They go on to describe Mao’s involvement in rural health care, the function of unofficial or voluntary organizations, the uses of the law and the press, and the methods of local administration. In every case we see two things at work: local or at least noncentral bodies trying things out, being observed or finally noticed at the center; and central control then being brought to bear, including or adapting some of the bottom-up ideas and actions, while snuffing others out.

According to Heilmann, a strategy Maoists called “proceeding from point to surface” meant that a local initiative, if encouraged from the center, could become a “model experience” and then national policy. Such procedures appeared as early as 1928, during the years when Communist forces were active in the countryside and long before Mao rose to supreme power inside the Party. “In sum,” writes Heilmann, “experimentation has been a core feature of the Maoist approach to policy- making since revolutionary times.”

These experiments may have begun with another Party member, Deng Zihui, who consulted local people about their ideas on land reform. Mao, working elsewhere, was impressed by Deng’s findings (although in 1955 he characteristically attacked Deng’s rural experiments as “right opportunism”). After the establishment of the remains of the Party at Yan’an in 1936, local Party activists at a “base area” some distance away were instructed to become “labor heroes” in experiments with land reform. One of the leaders of such efforts was Deng Xiaoping, and Heilmann suggests that the “active experimentation…may have exerted considerable influence on his approach to policy-making in the later stages of his political career.” Mao would declare such experimentation to be “much closer to reality and richer than the decisions and directives issued by our leadership organs” and that, as Heilmann writes, it “should serve as an antidote against tendencies towards ‘commandism’ within the party.”

This statement strikes me as ironic when we consider Mao’s early violence against those who appeared to defy him.2 Indeed, the Party’s basic position, which is to eliminate its enemies, is a weapon he handed down to all his successors. The perception that enemies, including fellow Party members, must be destroyed appeared as early as 1930 when Mao, still only a senior Party member, began the “AB”—the “Anti-Bolshevik”—campaign that led to the executions of some thousands of Party followers he deemed “objectively counterrevolutionary.” After 1949 this violence intensified.

Advertisement

Such brutality was characteristic, too, of Deng Xiaoping, who as Party general secretary oversaw the 1957 anti-Rightist campaign, resulting in the purge of hundreds of thousands, and who, in 1989, ordered the internal exile of the Party’s general secretary Zhao Ziyang and the Tiananmen killings. In 2010 Deng’s successors perceived the wholly nonviolent Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize winner, as a danger to their rule and, with considerable success, threatened foreign ambassadors who had been invited to Oslo to see the prize awarded to Liu in absentia, discouraging several from attending.3 This was not experimentation, but Maoist-style paranoia and persecution.

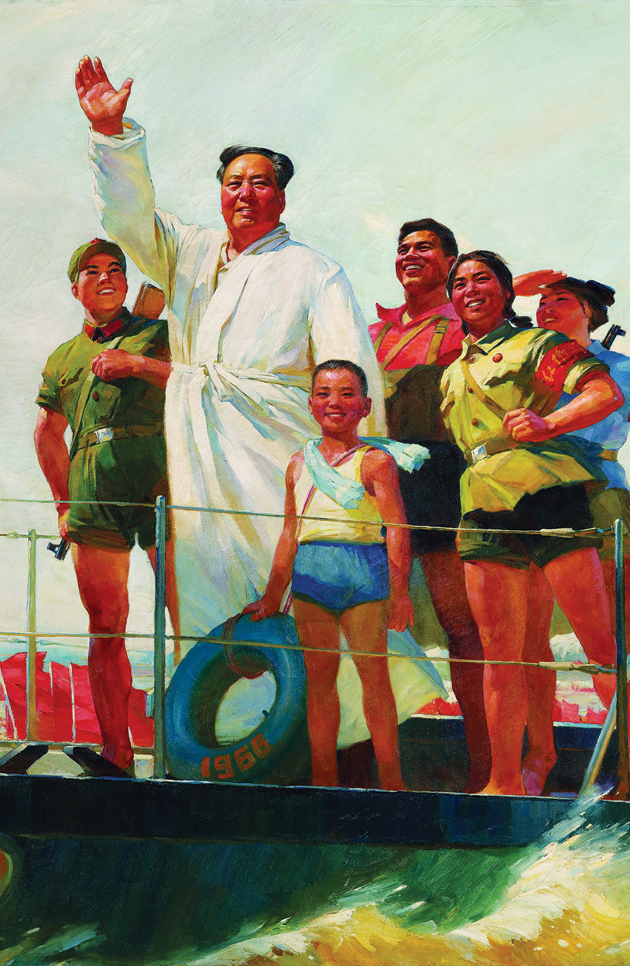

Even without violence, as Heilmann observes, “The party center always reserved, and regularly exercised, the power to annul local experiments or to make them into a national model.” By the 1950s, moreover, experimentation was weakened by the spread of central directives, especially during the ill-fated Great Leap Forward and the decade of the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976. After Mao’s death in 1976, top-level backing for experimentation, always under central supervision, resumed.

While Party historians attribute the notion of learning from local experiments to the chairman, Heilmann insists that this is not the case. It was, he says, John Dewey’s pragmatist philosophy, especially his emphasis on “intentional anticipation instead of…blind trial and error,” that had a great impact in China. Mao attended a lecture by Dewey in 1920, read one of his books, and had it stocked in the bookshop he opened that year. Dewey’s notions attracted open-minded Chinese thinkers like Hu Shi and James Yen—a Yale graduate—whose ideas were to influence the Communist plans to select rural districts for “intense and extreme experimentations.”

In her chapter on a possible civil society in China, Harvard’s Nara Dillon discusses China’s hundreds of thousands of “voluntary associations, non-profits, and other kinds of intermediate organizations,” such as charities, trade associations, and scholarly and recreational groups, including, for example, the Chinese Shakespeare Association. Dillon quickly observes:

Since few, if any, of China’s new voluntary associations and nonprofits are truly autonomous from the state, characterizing them as civil society seems premature. Indeed, many question whether China has ever had anything approaching a civil society.

Voluntary groups, she writes, existed in large numbers in the Republican period of the late 1920s and early 1930s, when their activities were circumscribed by numerous regulations. Those strictures were loosened in the United Front period during the anti-Japanese war. After the Communist victory in 1949, a series of “anti-corruption” campaigns attacked voluntary associations. For a time only “state-sponsored groups such as the official labor union and the Red Cross remained.” In the 1990s, a more relaxed attitude emerged, leading to the vast expansion of voluntary organizations, always closely observed by officials from the center.

Such organizations are part of a hierarchy determined by the degree of approval they receive from the state, with the women’s federations, youth leagues, and trade unions at the top. Always suspect, religious associations come next, and are under much firmer control, Dillon writes, than the groups in the first category. Finally, there are large numbers of informal and potentially illegal groups. Recently, a man was imprisoned for attempting to organize a group protest against the contamination of powdered milk, which had caused a few deaths and the illness of many thousands of children. Also placed under scrutiny—and in some cases detained for questioning—were hundreds of the signers of the manifesto Charter 08 calling for basic democratic freedoms, which led to the eleven-year imprisonment of Liu Xiaobo.

Indeed, as Dillon goes on to say, new regulations issued after Tiananmen in 1989, including the dismantling of even the Chinese Shakespeare Association, “suggest that one of the Chinese Communist Party’s…goals is to prevent the voluntary sector from turning into a civil society, and ultimately a force for further political reform.” Rather unconvincing, I fear, is her suggestion that “even if a democratic civil society does not appear to be on the horizon,” the voluntary organizations have “the potential to lead to more fundamental change.” In an otherwise excellent chapter, this hope, in 2012, sounds hollow. (The Party, for example, has recently warned “independents” not to run in grassroots elections.4)

Columbia Law School’s Benjamin L. Liebman, in his chapter on populist legality, states from the outset that “legal reforms have not imposed significant restraints on the party-state.” In 2012, the evidence for this view is only too stark. Legal reforms, Liebman continues, are used to serve state policies rather than to limit state powers and increase individual rights and interests. Nonetheless there has been an expansion of administrative law that stipulates how official bodies should act—although, Liebman adds, there is little enforcement of such regulations. Those seeking justice, he makes plain, “must do so strategically and within the framework of party-state leadership.”

In what may be a concession to optimism, Liebman suggests that legal experimentation “may lead to more robust legal institutions”—but may also “be an example of the arbitrary way in which law is often implemented in China.” Echoing the warning to mainstream scholars in Perry and Heilmann’s stimulating introduction, Liebman’s chapter shows that

China’s legal reforms have confounded those who argue that significant [legal] reform will necessarily give rise to political challenges to the state or that the party-state is not serious about such reforms other than as a tool for policy implementation.

While he is right to say that legal reform has aided economic development, for example, in improving conditions for trade and entrepreneurship, it is puzzling to say that because “the formal powers of the courts are weak,” the contemporary legal system is flexible, informal, and responsive to public opinion. As he himself writes, those seeking justice will find it not in the courts but, if at all, somewhere within the party-state. This seems hardly a “legal system.”5 Stanley Lubman of the law faculty at Berkeley has recently written:

It would be a mistake to think of China’s legal institutions as a “legal system.” Legal institutions in China, especially the criminal law, are part of a political system that ultimately directs their application and their use. They are essentially grounded on the dominant notion that law is to be used to keep the Party in power.

As The New York Times recently reported:

There are also growing concerns that a culture of nepotism and privilege nurtured at the top of the system has flowed downward, permeating bureaucracies at every level of government in China. “After a while you realize, wow, there are actually a lot of princelings out there,” said Victor Shih, a China scholar at Northwestern University near Chicago, using the label commonly slapped on descendants of party leaders. “You’ve got the children of current officials, the children of previous officials, the children of local officials, central officials, military officers, police officials. We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people out there—all trying to use their connections to make money.”

Yuezhi Zhao, who teaches at Simon Fraser University, includes in her chapter on the mass media an account of how retired high-ranking revolutionaries use the press, radio, television, and the Internet to lambaste the Party for abandoning its Maoist ideals. An Internet site was temporarily closed down in 2007 for posting “an open letter by seventeen former…officials and Marxist academics accusing CCP polices of making a mockery of Marxism and taking the country ‘down an evil road.’” We shouldn’t underestimate “the repressive and rigid nature of the CCP’s market authoritarianism,” Zhao warns, nor should we “exaggerate the significance, let alone idealize the democratic nature, of what has been described as the unfolding Internet-led ‘second cultural revolution.’” The thesis of Zhao’s chapter is summed up in this sentence:

The maintenance of a Leninist disciplinary core in the media system during a process of rapid commercialization ensures the media system’s continuing subordination to the CCP’s ideological objectives.

This was made all too evident by the treatment of the relatively moderate Hu Yaobang, an old comrade of Chairman Mao, who was purged as general secretary of the Party for his relative moderation in 1987, and whose death in 1989 set off the Tiananmen uprising. In 1985, two years before he was purged, Hu stated, in Zhao’s formulation, that “the CCP’s mouthpieces [i.e., in the mass media] are ‘naturally’ also the mouthpieces of the government and the people.” Hu said:

No matter how they [other businesses] are to be reformed…it is absolutely impossible to change the nature of party journalism in the slightest sense and change its relationship with the party.

I remember what must have been one of the Party’s ultimate nightmares when in May 1989 the staff of the official People’s Daily and their colleagues marched into Tian- anmen carrying an enormous horizontal banner reading “No More Lies.”

I can’t think of anything gloomier—and, regrettably, accurate—than the conclusions of the Oxford scholar Patricia M. Thornton in her chapter “Retrofitting the Steel Frame” on the way the Party maintains its control. Mao’s Invisible Hand shows conclusively and thoughtfully how, since Mao’s day, this has been achieved by allowing experiment but never letting slip the reins of power. Remembering Lenin’s warning that the Party must “struggle against spontaneity,” Thornton contends that it is indeed “remarkable” how quickly the party-state rechanneled the energies of the Tiananmen generation into economic modernization. What has this produced, Thornton asks? Following Zygmunt Bauman, she sees “a sea of suppressed anxieties, personal inadequacies, and longings that serve to lubricate the global machinery of capitalism.”

Behind these economic blandishments lies Mao’s invisible hand, the inspiration and justification for those who, in June 1989, ordered the murder of the students and workers in Tiananmen Square who had the temerity to shout “Down with the Party!” and “Down with Deng Xiaoping!” As so often in Party history, the Beijing spring was an experiment that had fatal consequences and is worth keeping in mind when we hear of the experiments undertaken within the party-state.

This Issue

June 21, 2012

Real Cool

How Texas Messes Up Textbooks

Mothers Beware!

-

1

Perry makes much the same points in her chapter “Sixty Is the New Forty” in The People’s Republic of China at 60: An International Assessment, edited by William C. Kirby (Harvard University Asia Center, 2011). ↩

-

2

Mao expanded this violence from the first years of his rule. See Klaus Mühlhahn, “‘Turning Rubbish into Something Useful,’” in Kirby, The People’s Republic at 60. ↩

-

3

Perry Link, “At the Nobel Ceremony: Liu Xiaobo’s Empty Chair,” NYRblog, December 13, 2010. ↩

-

4

See Chris Buckley and Michael Martina, “China Warns ‘Independents’ Challenging Party-Run Legislatures,” Reuters, June 9, 2011. ↩

-

5

For a comprehensive survey of the silencing of China’s human rights lawyers, see Jerome A. Cohen, “Turning a Deaf Ear,” South China Morning Post, June 7, 2011; for the retreat from earlier legal reforms, see Ong Yew-kim, “Ruling with an Iron Fist,” South China Morning Post, June 10, 2011. ↩