Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, with its grand opening chords, is one of the most recognizable and popular pieces in the classical music repertoire. Van Cliburn’s recording of the concerto, made after his victory at the First International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the height of the cold war, became the first classical album to go triple platinum, and the first LP that many classical music lovers owned. For many, the concerto is the sound of classical music. Yet the piano’s famous opening chords are not, in fact, what Tchaikovsky wrote at all. The actual musical text of the composition, as Tchaikovsky notated and conducted it on numerous occasions, has been distorted by interventions almost certainly introduced after his death. This year—both the 175th anniversary of Tchaikovsky’s birth and the 140th anniversary of the concerto’s premiere—the Tchaikovsky Museum and Archive in Klin, Russia is publishing a new scholarly edition of the First Piano Concerto, a text that will enable us to hear for the first time the version of the composition that Tchaikovsky himself conducted.

There are three versions of the concerto. Tchaikovsky himself was responsible for the two versions of the piece dating from 1875 and 1879. The third version was published posthumously after 1894. It is this third version that has been most commonly performed for over a century—for instance, this is the version that Van Cliburn performed—and it varies significantly from the two earlier versions. But the question of whether Tchaikovsky authorized the changes, or if they were the work of other musicians or editors, has until now gone largely unanswered.

At the end of 1874, Tchaikovsky showed a final draft of the first version of his piano concerto to his supporter, one of the foremost Russian musicians of the time, the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein. Not a concert pianist himself, the composer wanted to consult on the playability and effectiveness of the piano writing in the concerto. Rubinstein was scathing about both. Tchaikovsky describes this occasion in a letter to his patron, Nadezhda von Meck, and recalls Rubinstein telling him that the concerto was unacceptable, full of clumsy, trivial passages, and many stolen ideas. At the end of the meeting, Tchaikovsky wrote, Rubinstein said

that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing my piece at his concert. “I shall not alter a single note,” I answered, “I shall publish the work exactly as it is!” This I did.

Tchaikovsky completed this first version in February 1875 and dedicated the concerto to the great German pianist Hans von Bülow, an admirer of his music. Von Bülow responded to the concerto with great enthusiasm and premiered it in Boston in October 1875. A student of Tchaikovsky’s, the pianist and composer Sergey Taneev, gave the first performance in Moscow in December 1875 with the now less doubtful Rubinstein on the podium.

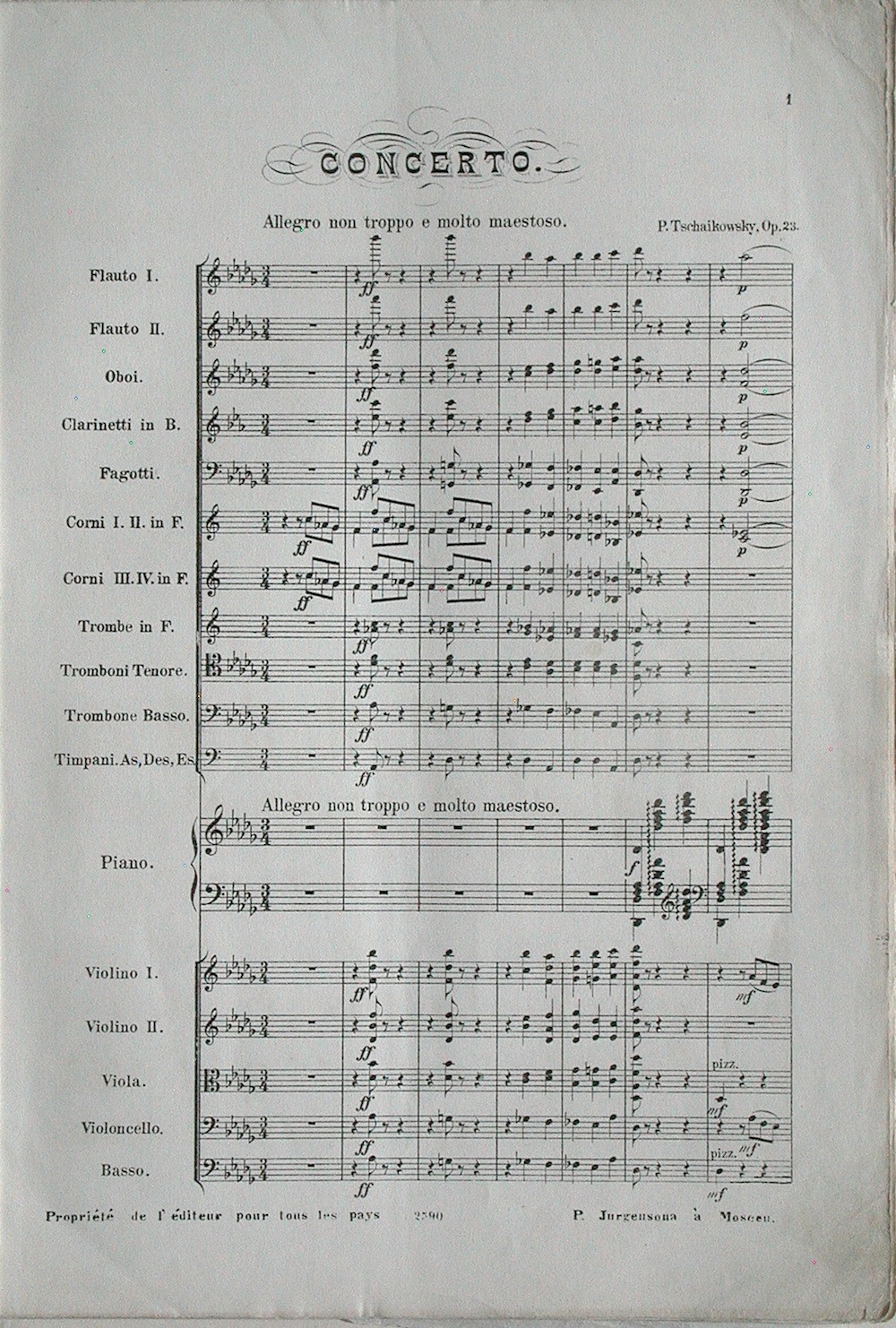

Shortly after these early performances Tchaikovsky decided to make some alterations to the piano part, making it more sonorous and playable while leaving both the musical material and the overall structure intact. With these changes incorporated, the second version of the concerto was printed by his publisher, P. Jurgenson, in 1879. From then on, it was this 1879 version that Tchaikovsky conducted, right up until his very last performance in St. Petersburg on October 28, 1893, days before his death.

It is impossible to know for certain just who is responsible for the posthumous version. The name of Alexander Siloti, a student of Tchaikovsky’s, is most commonly mentioned in association with the changes in Tchaikovsky’s text. Siloti is quoted by Olin Downes in a New York Times article of October 13, 1929:

Some time after the first and second editions had appeared, Mr. Siloti informs us, he ventured to speak to Tchaikovsky about these matters. The young musician played the opening chords on the piano. “That’s what you want, isn’t it?” “Why, yes,” replied the composer, astonished, “it’s what I’ve written, isn’t it?” “No. That’s just the point. It’s what I’ve played.” Siloti had transposed the chords of the right hand an octave higher than Tchaikovsky had written them—transposed them as they stand today. Siloti suggested other changes, and a short cut in the last movement.

There is documentary evidence that Siloti and Tchaikovsky discussed a proposed cut in the last movement, and that some further changes to the concerto were contemplated. However, the existing correspondence between them does not mention changing the opening chords, nor other alterations that actually ended up in the posthumous version.

Siloti’s New York Times interview contains a number of inaccuracies relating to the history of the concerto. Siloti mentions the third edition of the concerto being published by P. Jurgenson during Tchaikovsky’s lifetime and claims he was not credited as the editor because he was so young at the time. Yet the publishing house’s records show that, following the second version of 1879, no updated edition of the concerto was brought out by Jurgenson until 1894, a year after Tchaikovsky’s death. And it is hard to believe Siloti’s boastful claim that Tchaikovsky had not noticed the changed opening chords.

One can only speculate about the reasons why the posthumous edition became the prevalent one in the twentieth century. It was probably due to a confluence of factors, among them: the limited number of copies in the early printings of the concerto; the fact that additions and alterations by virtuoso performers was an accepted practice of the time; a widespread but unfounded view among pianists that Tchaikovsky did not know how to write “pianistically”; and Siloti’s claims that the changes were authorized by the composer himself.

Doubts about the authenticity of the third version surfaced early on. As the Russian pianist Konstantin Igumnov is quoted in a 1979 Russian book Pianists Speak:

The third version … introduces significant changes to the original text. The chordal accompaniment of the opening theme is altered (thicker voicing, increased dynamics and introduction of solid chords instead of the arpeggiated ones in the original). The range of the final restatement of finale’s secondary theme is changed, and a cut in the development of the third movement is made. … We are convinced that the composer, and not his editors, is right.

Sergey Taneev, in addition to giving the concerto’s first performance in Moscow, helped in the preparation and copying of its score and orchestral parts, and was one of the early exponents of the piece. In a letter to his brother, Tchaikovsky described how gloriously Taneev played his concerto. Thus, Taneev’s 1912 letter to Igumnov, expressing his disbelief in the authenticity of the third version, is particularly significant:

The [opening] chords sound excellently on the piano (I remember them in N. Rubinstein’s performance) and why one should prefer the ideas of “editors” to what the composer himself wrote is beyond me. … If in addition to all else, one adds the extremely quick tempi that go beyond the limits of what is indicated in the composition (for example listening to the middle part of the andantino movement one could think that it is a prestissimo, when indicated is only an Allegro vivace assai), my dissatisfaction with the performance of the concerto will be quite understandable. I believe it is necessary to return to the author’s text, to forget what overzealous editors put in the composition on their own, and to perform it according to the author’s intentions.

The editorial team of the Tchaikovsky Museum and Archive, led by its senior researcher, Dr. Polina Vaydman, has examined what is to date the most complete set of materials relating to the concerto: all extant autograph manuscripts as well as numerous copies of the printed score dated pre and post Tchaikovsky’s death. Of special significance among the studied sources is Tchaikovsky’s own conducting score with handwritten performance markings that he used in his last public performance on the 28th of October, 1893. The fact that this score of the 1879 version was the one from which Tchaikovsky conducted just before his death further suggests that the third version was not executed with Tchaikovsky’s participation, and that he did not definitively authorize further changes for publication.

Comparing the 1879 version with the posthumous one, I find the editorial changes in the third version add a superficial brilliance to the piece, while at the same time detracting from its genuine musical character. Many examples of differing dynamics, articulations, and tempo indications in Tchaikovsky’s version point to a more lyrical, almost Schumannesque conception of the concerto. The arpeggiated chords and softer dynamics in the opening do not threaten to overpower the theme in the strings and allow the melody more metric flexibility and differentiation. Restoring the measures traditionally cut in the middle section of the finale enables us to hear harmonically and contrapuntally adventurous combination of several motivic strands. The extended middle section allows for an introduction and deeper immersion in a new mood. In the posthumous version, this section of the finale is so short that the new mood introduced always seemed a jarring miscalculation. It would now appear that this miscalculation was not the author’s, but his editor’s.

Tchaikovsky said that composing was a lyrical process for him, and the First Piano Concerto in his own version shows a strong lyrical and noble vein that the better-known posthumous version negates.

Advertisement

We present below excerpts from Kirill Gerstein’s new recording of the First Piano Concerto—the first ever based on Tchaikovsky’s own 1879 score—alongside samples from a recording of the posthumous edition. Each sample is accompanied by commentary from Kirill Gerstein.

—The Editors

In Tchaikovsky’s 1879 version of the concerto, the arpeggiated chords in the opening of the piano part allow for a more flexible metric shaping and lyrical coloring of the orchestral melody than the bombastic block chords of the posthumous version.

In the posthumous edition, the middle episode of the concerto’s second movement (heard at 1:22 in the sample from Gilels’s recording and 1:09 in the sample from my own) is marked prestissimo and is often played so quickly that the melody sounds almost like cartoon music. Tchaikovsky’s own marking is a less extreme allegro vivace, which allows for the entire section to be played at a lively waltz-like tempo.

The passage of slower music that has been traditionally cut from the finale can be heard in the second sample below. When this passage is removed—as it has been in the first sample—the whole section becomes so short that the introduction of a different mood seems a jarring miscalculation.

The final cadenza in the posthumous version has acrobatic octave jumps at the end of the passage and a fermata, or hold, before the final restatement of the melody. What Tchaikovsky actually wrote is a slow, almost vocal trill, arranged in octaves, that flows into the final statement of the melody. His own edition does not include the pompous fermata. The cadenza thus becomes a preparation for an emotional breakthrough into the final, joyous episode, rather than a virtuosic insert.

Kirill Gerstein’s recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto is available from Myrios Classics.