“We need to broaden and diversify our gaze,” Linda Colley asserts in The Gun, the Ship, and the Pen. Her dazzling global history does just that, pulling away the blinkers of national stories, widening the focus, and showing—as the current pandemic has done—how interconnected all our lives and interests are. In this bold, packed account of the growth of written constitutions from the mid-eighteenth century until the advent of World War I, a web of connections spins between continents, entangling, clashing, looping back, increasing in speed and complexity. In a daring revisionist move that overturns explanations of the proliferation of constitutions “only by reference to the rise of democracy and the lure of certain (mainly Western) notions of constitutionalism,” Colley foregrounds warfare, particularly naval warfare, as the spur and points to the many military men involved in constitution-making: hence the guns and ships of the title, although the ships reappear in more peaceful guise, carrying nineteenth-century exiles and future leaders as they gather ideas across the world.

Colley is a professor of history at Princeton, and the broader perspective she demands of her readers also marks her own academic journey. Her first book, from 1982, was a study of Britain’s Tory Party; she went on to a highly original account of nation-making in Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (1992) and then to the casualties and strains of empire in Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600–1850 (2002). Other books have intervened, all with a keen sense of issues concerning identity and the intermeshing of particular histories with wider struggles for power.

Now she takes on the entire world, at war and at peace. The initial lever for political change, she argues, was the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), which spread beyond Europe to India, North and South America and the Caribbean, Senegal, and the Philippines. In the aftermath of this and later wars and revolutions, constitutional thinking developed both as a means of shoring up entrenched power and of turning successful rebellions into legitimate governments.

In the most basic terms, a written constitution is a single document that stands above the law, clarifying the relationship of the executive, legislature, and judiciary, as well as the duties and rights of citizens. One enduring notion is that such a document should embody certain values considered immutable, such as liberté, égalité, fraternité. Sadly, in practice, when regimes are concerned with asserting their power, “liberty” and “justice” come low on the list. But the belief in universal values goes back to the Enlightenment origins of this “new political technology,” as Colley calls written constitutions. Thus she shows Jeremy Bentham, queried by the German law professor Eduard Gans in 1831 on the relationship between lawmaking and local history, exploding, “Do you actually value history?… This upholder of mindlessness, this page on to which intellect and stupidity are equally written.” Furiously, Bentham asserted that written constitutions should instead, as Colley explains, “embody rational principles of liberal justice and rights that were of universal application.”

Colley’s account contradicts Bentham’s bluster. Taking us at different points to Corsica, Japan, the US, China, Venezuela, Sierra Leone, and many other nations, she shows how historical events and local traditions have always been crucial to constitutional development. The geographic sweep and legal complexities are daunting, but Colley makes them accessible by employing a human scale, evoking settings and individuals—from the “white-haired, trim and restless” Bentham, strolling round the gardens of his London house, to the Japanese prime minister Itō Hirobumi at the end of the nineteenth century, wearing Western dress and then reverting to his kimono, “a white or pale one in summer and a black one in winter.”

In this vein, she opens not with the French Revolution or the American War of Independence but with the thirty-year-old Pasquale Paoli, soldier and Freemason, returning to Corsica on April 16, 1755, determined to free his native country from Genoese rule and French encroachment. That November, by then a successful rebel leader, he drafted a ten-page constitution, declaring that the representatives of the people, now “legitimate masters of themselves” after having regained Corsica’s liberty, wished “to give a durable and permanent form to its government by transforming it into a constitution suited to assure the well-being of the nation.” Paoli drew ideas from the classics, from contemporary writers, and from his father’s own local attempts at reform. A decade later, all Corsican men over twenty-five could vote and run for a seat in the diet, the island’s parliament—a higher proportion than anywhere else in Europe. But enfranchisement was less an assertion of principle than an acknowledgment of the need for willing troops: If a man had no political rights, asked Paoli, “what interest would he take in defending the country?”

Advertisement

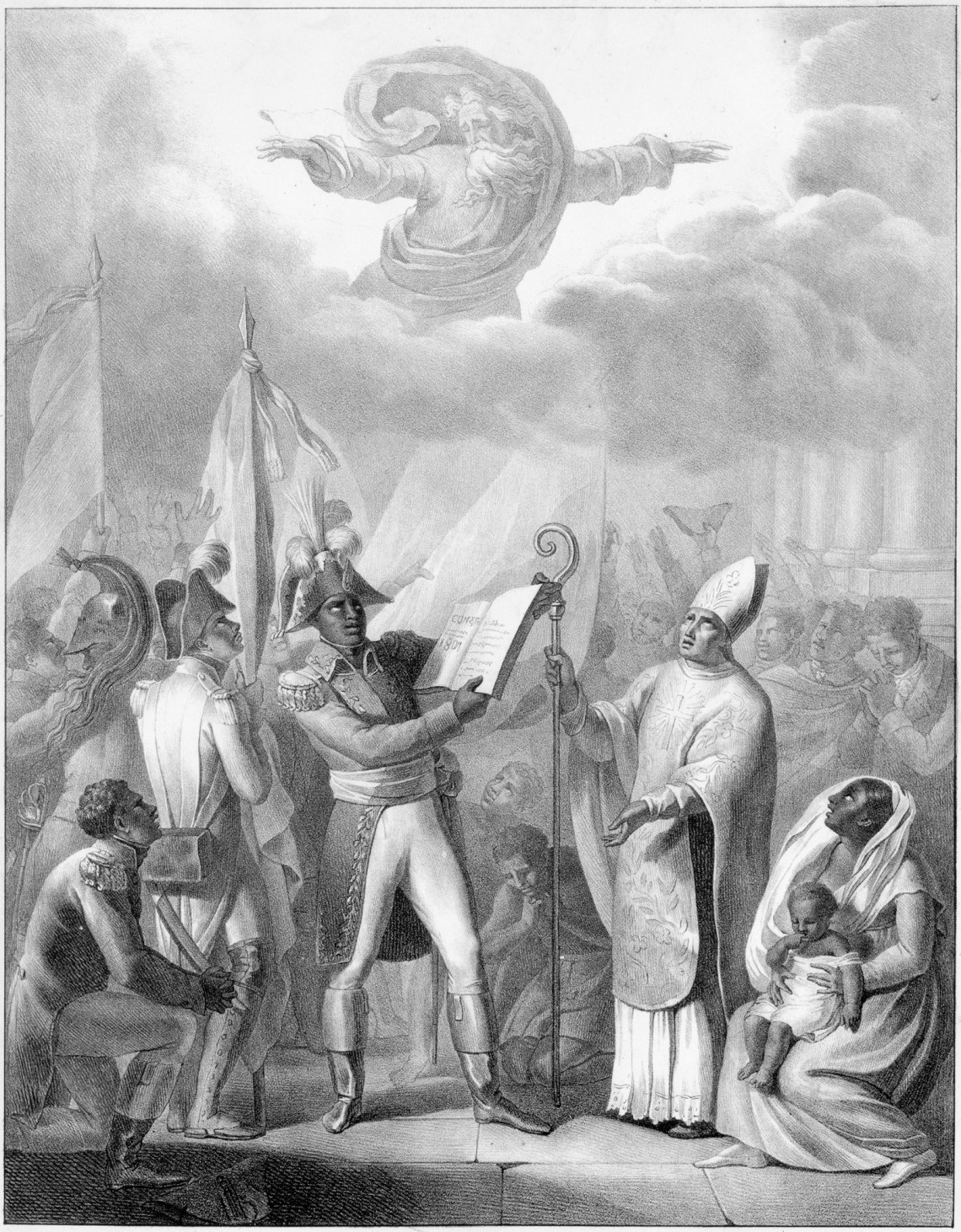

The models for early written constitutions, even those born of revolution, were not necessarily republican. Paoli, scribbling his constitution in Corte, “a fortified town high in the granite heart of the island,” is set against Henry Christophe in Haiti fifty years later. Christophe used his 1811 constitution, modifying earlier constitutions of Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, to declare himself a hereditary monarch. Posing for his portrait in military dress against a background of rolling clouds, he presented himself as “a soldier king valiantly engaged in defending a realm whose very independence had been secured by Black warfare.” A monarchy, Colley points out, could be revolutionary, if claimed by “an uneducated Black artisan, turned drummer boy, turned innkeeper, turned butcher,” then a general and a self-proclaimed king.

Established rulers too, nervously reestablishing control after the Seven Years’ War, embarked on constitutional projects. In 1765, three years after her coup and the death of her husband, Peter III, Catherine the Great spent eighteen months—rising every morning between four and five, enduring eyestrain and headaches—compiling her Nakaz, an agenda for modernizing the laws of the Russian Empire. Among her many borrowings were sections of important Enlightenment texts—Beccaria’s On Crimes and Punishments (1764), the Encyclopédie, and Montesquieu’s The Spirit of Laws (1748), which she called “the prayerbook of all monarchs with any common sense.”

Catherine needed to bolster her position: as “a female usurper” who faced sexual innuendo and personal as well as political threats, she ruled a country overextended in war and consumed by debt. Yet while the Nakaz reaffirmed her power to make and repeal laws, the Legislative Commission that discussed it was stirringly innovative, gathering delegates from across the empire, including women landowners and “state peasants”; Colley observes that “in sharp contrast with the men of Philadelphia in 1787, not all of the Moscow deputies were white, and not all of them were Christian.”

Other European rulers engaged in similar projects, notably Frederick II of Prussia and Gustav III of Sweden, whose Form of Government, proclaimed as “a fixed and sacred fundamental law,” was published in 1772 with the provision that both king and people were “bound to the law, and both of us tied together and protected by the law.” Catherine and Gustav had their documents printed and distributed at home and abroad. (The Nakaz was censored as “dangerous and advanced” in France.) From then on, the printing press, as much as the pen, was a powerful driver in circulating different constitutional possibilities.

At the same time, the Persian ruler Nadir Shah Afshar was waging war from the Caucasus to India, and the Qing Dynasty was annihilating the Zunghar-Mongolian Empire. The Chinese conquests contributed to the “blizzard of new paperwork” across the globe. An army of scholars and officials worked for eighteen years on the Qianlong Emperor’s Comprehensive Treatises, a reference source for officials in the newly conquered lands, as well as a propaganda exercise to demonstrate his power; they were published in 1787, the same year as the drafting of the American Constitution.

Subjects, as well as rulers, pondered constitutional issues. Colley argues that this was particularly true in Britain, where “because of the limits on royal power, such developments were less top-down and more diverse.” Royal prerogative had already been circumscribed by the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and the Bill of Rights that followed ensured free elections and certain civil rights. Yet Tom Paine, one of a growing number of excise officers raising the money needed to pay for the Seven Years’ War, was convinced, in Colley’s words, that “monarchies were congenitally addicted to warmongering,” and he became a powerful advocate for written constitutions. Paine looked not to contemporary texts but to earlier charters such as the thirteenth-century Magna Carta, the object of a revived cult and the foundational “liberty text” that was repeatedly cited by radical groups fighting for more rights, including the Chartists of the 1830s and 1840s.

In Colley’s narrative, Paine “the charter man” stands for three crucial features: grassroots involvement, the authority of the past, and the bold transmission and recycling of ideas—another example of the power of print. In Common Sense, published in 1776, two years after he landed in America, Paine recommended that a congress, with two members for each of the thirteen states, should “frame a CONTINENTAL CHARTER, or Charter of the United Colonies; (answering to what is called the Magna Carta of England).”

Twelve years later, in the long, hot summer of 1787, many of the delegates gathered in Philadelphia to amend the Articles of Confederation drawn up during the Revolutionary War referred to the earlier charters for the different American colonies. Once the draft of the Constitution was published, Colley argues, print was essential to its ratification. This was bolstered not only through the Federalist Papers of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton (which stressed that the Constitution would defend the new nation against armed threats from abroad and insurrections from within, more than they celebrated its new beginnings), but through its dissemination by newspapers, magazines, and broadsheets all across America and the world.

Advertisement

Yet for outsiders the US Constitution was both a model and a warning. On one level, Colley writes, the expanding web of state constitutions provided

exceptional levels of white male democracy and opportunity. At another level, however, many of these same documents helped to further, order and legitimise the appropriation of other peoples’ lands on the part of advancing armies of mainly white settlers, thereby acting as building blocks for the construction of a continent-wide American empire.

When the Cherokee people, alarmed by white invaders, held a convention in 1827 and adopted a constitution setting out the borders of their territory, it was quickly declared illegal by both the US government and the legislature of Georgia, where most of them lived. In the following decade the Cherokee were driven from their lands. “The opportunities and ideas made available by print,” Colley notes, could be quickly “pushed to one side by those in possession of superior levels of power.”

When the early constitutions laid down a franchise, they almost always excluded certain categories, particularly women, Blacks, and indigenous peoples. The exceptions stand out. One was the Plan de Iguala, issued in Mexico in 1821 as an intended blueprint for the country. It selected some elements from the American Constitution, but it also specified that “all the inhabitants of New Spain, without any distinction between Europeans, Africans, or Indians,” would be citizens, with “access to all employments according to their merit and virtues.” It was widely published, and its inclusiveness (though still limited to men) was quickly picked up by campaigners in other parts of the world, from Irish writers concerned at the lack of Catholic Irish representation in the Westminster Parliament to the remarkable James Silk Buckingham and Rammohan Roy in Calcutta, who campaigned for improved liberties and rights for India’s indigenous peoples. Colley writes powerfully about those who lost out or were excluded, noting that until World War I the treatment of women often became more rather than less restrictive as constitutions were amended.

“Superior levels of power,” though, trumped any drive for wider liberties. Napoleon, whom Colley sees, in a slightly forced trope, as a model for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein—both as a monster fond of reading about the founding of ancient republics and as a scientist whose experiment lets loose lasting violence and chaos—declared that “conquered provinces must be kept obedient to the victor by psychological methods” and by changes in “the mode of organisation of the administration.” But his greatest influence in this field came not with his new Cisalpine and Westphalian republics, swept away by conflict, but almost by accident. Before defeats at sea limited his global imperial ambitions, Napoleon’s Statute of Bayonne, drawn up in 1808 after the invasion of Spain, envisaged a constitution applicable to all of Spain’s overseas territory.

This spurred the opposing Spanish cortes, which met in Cádiz in 1810, to draft a rival constitution. The Cádiz constitution granted a measure of citizenship to all ethnicities in Spanish territories from the Philippines to Chile. Although Spain’s empire collapsed, the Cádiz constitution proved “massively influential, even game-changing.” The fact that it came from a Catholic nation (so far, most constitutions had been published under Protestant regimes) encouraged priests in Mexico, for example, to support their country’s new constitution in 1824, ensuring its widespread dissemination and acceptance. Yet in the newly liberated South American states, many constitutions were born and died with startling rapidity: “Our treaties are scraps of paper,” sighed the liberator Simón Bolívar (who recommended aspects of the British system), “our constitutions empty texts.”

The Gun, the Ship, and the Pen traces these shifts and abounds with subtle arguments grounded in expertly marshaled sources, generously acknowledged. But perhaps the book’s most impressive aspect is its mobility, felt not only in the fluid narratives but in the movement of constitutional ideas themselves. Hurried on by war, political and legal theories and models jump from nation to nation, continent to continent, carried by newspapers, books, and official documents, expressed in speeches, thrashed out in congresses, and argued over by exiles and dissidents. Endlessly adaptable, once published they could provide regimes “with an exportable and sometimes charismatic manifesto and vindication.”

Even small, ad hoc examples could be seeds for change. In 1790 the mutineers from HMS Bounty took refuge on tiny, volcanic Pitcairn Island with eighteen Tahitian companions, mostly women. When Captain Russell Elliott landed there in 1838, he found one hundred “predominantly non-white, mixed-culture” people. Listening to their anxieties about the arrival of missionaries, American whalers, and traders, and their fears that they had no flag and no government and that their island was easy prey, Elliott handed out a spare Union Jack and drew up “a few hasty regulations.” These ranged from protecting their scant resources (the first example of a constitution attending to the environment) and making children’s schooling mandatory to planning the election of their “magistrate and chief ruler,” who could assume no power “without the consent of the majority of the people.” Furthermore, all native islanders and long-term residents over eighteen, male and female, would have “free votes.”

This startlingly democratic constitution, sometimes written off as a “picaresque episode,” a utopian whim on Elliott’s part, was, Colley argues, no marginal venture but an inspiration across the Pacific. Other Pacific islands would develop texts to cement local unity and ward off other powers. These included the political code of Pomare II of Tahiti and Hawaii’s constitution of 1840, designed to show the island as a modern state and “therefore not an appropriate target for imperial takeover,” which enabled it to fend off American annexation until 1898.

Ideas spread like ripples. The Hawaiian model “of calculated repositioning and defensive modernisation” may, Colley argues, have influenced the Tunisian constitution of 1861, the first written constitution of an Islamic state, which was, she notes, at once ambivalent and lastingly significant. While granting no voting rights or freedom of expression or assembly, it accepted all residents as equal before the law, since they were all “creatures of God.” And although the ruling bey was confirmed as a hereditary prince, he was now required to act through his ministers and council. Other Muslim states took note. Even the Ottoman sultan accepted a constitution modifying his powers in 1876, and the influence of this early assertion of the possibilities of political change turned possession of a written constitution into an anticolonial statement, a spirit that could still be felt in the new Tunisian constitution of 2014 that followed the Arab Spring of 2011–2012.

The 1860s, like the 1750s, were another decade of crushing wars: the US Civil War, the Crimean War, the War of the Triple Alliance (Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay) against Paraguay, and the crushing of the Taiping Rebellion in China. Once again, conflict was followed by constitutional change in several widespread parts of the world. The American Reconstruction Act of 1867, for instance, which granted voting rights to Blacks, inspired the New Zealand government to grant rights to the Maori male population, and prompted James Africanus Horton in Sierra Leone to draw up proposed constitutions for independent West African nations.

Toward the end of the century, however, attention turned from the West to the East, where the new constitution of Meiji Japan, a deliberate constitutional leap into the modern world, was of major significance. “A large polity which was not situated in the Western world, which was not Christian, and which was not inhabited by people who viewed themselves as white” had, Colley notes, produced a document combining Western provisions, many gleaned in London, with historical continuity and a (very limited) embedding of popular rights. National and international opinion linked Meiji victories against China in 1895 and Russia in 1905 directly to this embrace of change. The Japanese, said one Turkish commentator, “are fighting for a country where they are free.”

Colley’s far-reaching account ends, as it began, in conflict, with World War I and the shaking of the old imperial powers. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Soviet Republic’s Fundamental Law, with its opening “Declaration of the Rights of Labouring and Exploited People,” provided a new, socially aware reference point for constitution writers. Many of these post-1918 constitutions failed—that of Germany’s Weimar Republic perhaps most memorably—but World War II and the waves of civil wars that gained momentum after the 1950s brought yet more. Since the 1990s, Colley notes, “the rate of flux and constitution-manufacture has only quickened.”

Preserving constitutions can become a cult, making them lumbering vehicles at odds with changing times: Colley suggests that the difficulty of amending the American Constitution is one reason for the “political dysfunctionality and hampering divisions” that have marked the US in recent decades. Today only a few countries—including Israel, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—lack a written constitution.

As a British historian, Colley admits that until she moved to the United States, constitutions seemed “profoundly exotic,” a phrase suggesting not only texts from “outside” but something decorative and unnecessary. Britain has a “constitution,” of course, but its elements enshrined in law evolved over centuries, rather than in a single document. Yet at times many Brits, including me, might agree with Tom Paine, who wrote in The Rights of Man (1791) that a constitution has “not an ideal, but a real existence; and wherever it cannot be produced in a visible form, there is none.” A written text could, one feels, have spared us the Brexit agony by laying down terms for a referendum, as well as checking betrayals of ministerial responsibility. It might even—utopian dreams—tackle poverty and inequalities of race and gender.

Britain does have recourse to the invaluable European Convention on Human Rights, drafted in 1950, an inspiring example of a supranational “constitution,” which is outside the sphere of Colley’s book. A constitution, even today, can offer at least a hope of protection for the individual against the overwhelming power of the state. However vain that trust, its potency is suggested by the images with which Colley ends her book—a young Pretoria demonstrator shielding his face behind a copy of the constitution signed by Nelson Mandela in 1996, and a Russian girl protesting in 2019 by reading passages from the state constitution. The surrounding soldiers, Colley believes, with an uncharacteristic flash of hope, recognized the words and the text, and did not attack her.