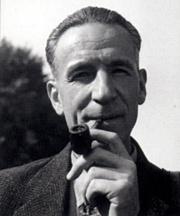

“The French photographer André Zucca was not a Nazi,” Ian Buruma writes in his recent article on Paris during the German occupation, “but he felt no particular hostility to Germany either…. Zucca simply wanted to continue his pre-war life, publishing pictures in the best glossy magazines. And the one with the glossiest pictures, in fine German Agfacolor, happened to be Signal, the German propaganda magazine.” Born in Paris in 1897, Zucca worked for both French and foreign publications in the 1930s, and covered the Russian–Finnish War in the winter of 1939–1940 for Paris-Soir, before becoming a photographer for Signal from 1941 to 1944. After the liberation he was arrested but never prosecuted, and spent the remainder of his career as a wedding and portrait photographer in a small town west of Paris. He died in 1973. Recently, a volume of Zucca’s controversial wartime pictures of Paris was published in France. Here is a selection from it with comments by Buruma. —The Editors

The only threatening thing about Zucca’s photograph, taken in 1942, of two German airmen at the tomb of the unknown soldier in Paris, is the dagger suspended from the officer’s belt; and even that looks more ornamental than like an actual murder weapon. The man on the left is fiddling with his camera, the man on the right, the one with the dagger, is looking on, perhaps with a word of advice on how to take the best picture of the Arc de Triomphe looming over their heads. On the stone bench beside them lies a guide book to the French capital. Everything about this picture emphasizes what French people at the time, pleasantly surprised by the good manners of German soldiers stationed in Paris, called correct. Even the respect shown for a tomb containing the remains of Germany’s old foes in World War One is a sign of civilized behavior. That much of the behavior of Germans stationed in Paris was anything but civilized is carefully hidden from view. As in most of Zucca’s wartime pictures, what is left out is what needs to be further investigated.

They could be country bumpkins on a rare visit to the big city, those German soldiers peering at a horse in the paddock of the Longchamp racecourse in August 1943. There is a slightly disapproving look on their faces, as though they have just lost their last French francs on unwise bets. Or perhaps they feel out of place amidst the flashy horse owners and their silk-clad jockeys. Like awkward adolescents at a high school prom, they would like to make their presence felt, but don’t quite know how. It is hard to imagine this scene in Poland or the Ukraine. There, they knew all too well how to make their presence felt.

Even the polar bear at the zoo in Vincennes looks disgusted with the Germans. His head lies on the slab of rock, contemptuous of the German soldier staring at him. We see the soldier in his feldgrau uniform and his pale, close-shaven pink neck from behind. It is hard to imagine satirical intent on the part of Zucca. But it is also difficult not to see the bear, trapped, exhausted, disdainful, as a symbol of the French population. Perhaps satire can be unintentional.

Jean Baronnet’s Les Parisiens sous l’Occupation: Photographies en couleurs d’Andre Zucca was published in Paris by Gallimard in 2008 and reviewed by Ian Buruma in “Occupied Paris: The Sweet and the Cruel,” which appeared in the December 17 issue of The New York Review.