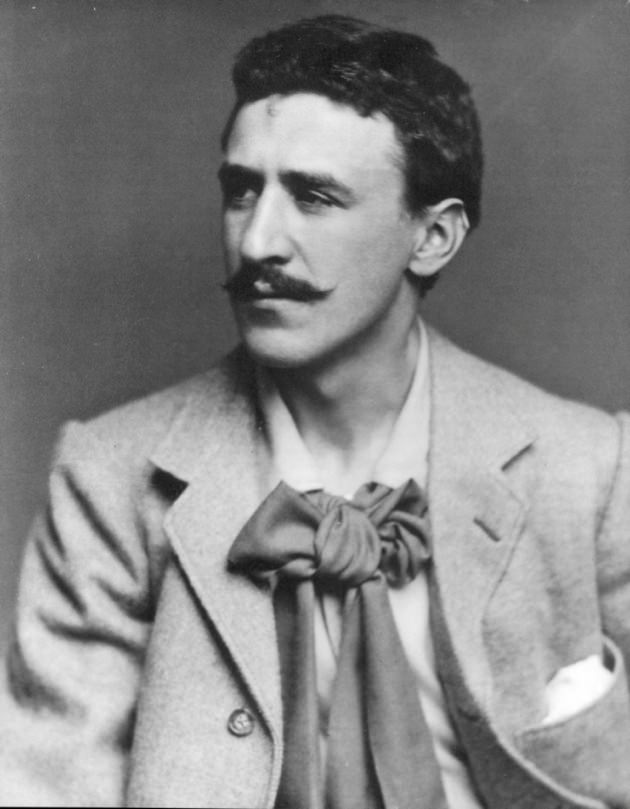

The public’s outsized affection for the Scottish architect and furniture designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) is all the more remarkable since as late as the mid-twentieth century his place in history was by no means secure. His stature rose, however, with the 1960s revival of interest in his small but exquisite output (much of it ephemeral interior decorating schemes). Indeed, Mackintosh’s hometown of Glasgow has in recent years developed a thriving cultural tourism industry largely because it contains nearly all his executed buildings, fewer than twenty in toto.

Mackintosh was saved from utter obscurity after his death at sixty following fourteen professionally fallow years (during which his major project was a sequence of highly stylized botanical watercolors), when the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner cited him in his landmark Pioneers of the Modern Movement (1936). But Pevsner, who focused on only those aspects of nineteenth-century and fin-de-siècle work that led to the mechanistic modernism he favored, defined Mackintosh too narrowly as a forerunner of the pared-down International Style.

That same line was taken in the landmark life-and-works Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement (1952) by Thomas Howarth, who until his death, in 2000, reigned as the doyen of Mackintosh studies (and foremost collector of his now-stratospherically valuable artifacts). So it’s particularly refreshing that Howarth’s place as the most authoritative scholar on the Scots master has finally been taken by a Glasgow-based architectural historian with a far more nuanced perspective. James Macaulay, in his recently published Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Life and Work offers a convincing corrective to Mackinstosh-as-proto-modernist that stresses the subject’s deep roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Macaulay is a such an archetypal Caledonian—he peppers both his conversation and his writing with quaint Scotticisms such as “douce” (sober or sedate) and “feu” (a land holding)—that one feels a strong local connection with Mackintosh just by speaking with or reading him. His argument is aided by Robert L. Wiser’s superb book design, which in its airy layout and Glasgow School display type vividly evokes the subject’s all-encompassing aesthetic while remaining both manually manageable and easily legible, as many outsized, stylistically exaggerated Mackintosh tomes are not.

Macaulay does an excellent job of detailing the preoccupations of Mackintosh and his closest collaborators, known as The Four. This working family circle included his long-suffering but ever-loyal wife, the decorative artist Margaret Macdonald; and her sister and brother-in-law, Frances Macdonald and J. Herbert McNair. The siblings contributed decorative elements, McNair devised architectonic furnishings, and “Toshie,” as they called him, tied it all together as the architect-in-charge.

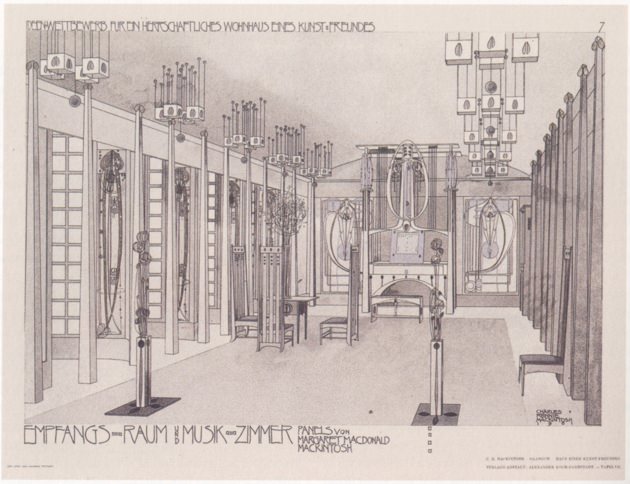

In search of spiritual communion through design, all were much influenced by the Symbolists, particularly the Belgian writer Maurice Maeterlinck. His otherworldly fables of enchanted princesses confined in paradisiacal walled gardens or sacred groves directly informed a number of intricately embellished schemes, a handful still extant but most now lost, like the stunning model rooms at widely publicized avant-garde design exhibitions in Vienna (1901) and Turin (1902).

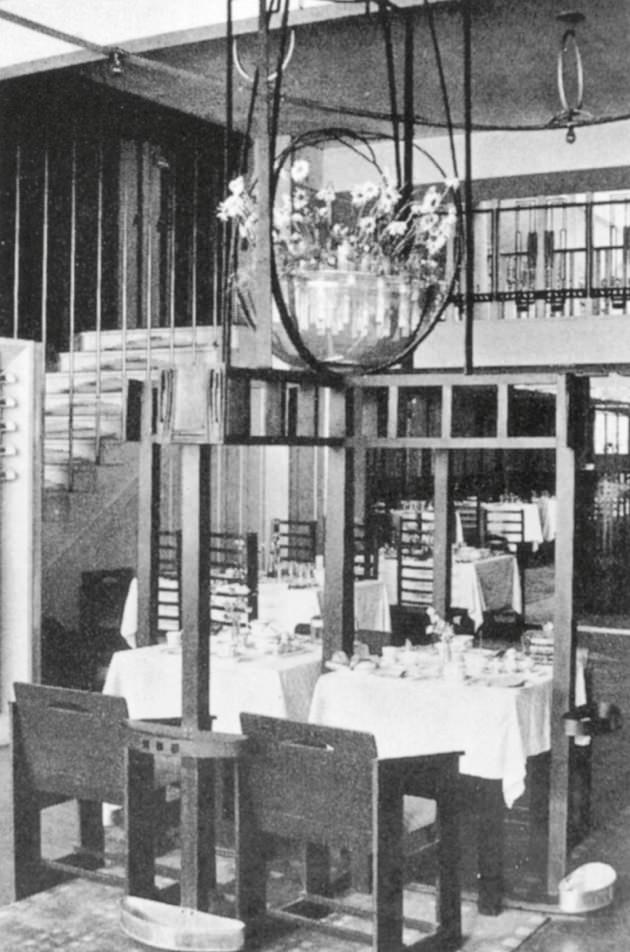

One of Macaulay’s major themes is the recurrence of arboreal references in Mackintosh’s interiors, a unifying thread that ran through the work of The Four in several mediums. For example, in his virtuoso series of temperance tea-rooms in Glasgow’s city center for the reform-minded Catherine Cranston, he devised stacks of multistory dining areas that employed a tripartite root-stem-flower or root-trunk-branch motif—either used either in a single representation on each floor, or, where there was a vertical light well (as in his tour-de-force Willow Tea Rooms of 1902–1904), expressed as a continuous organism from ground to rafters.

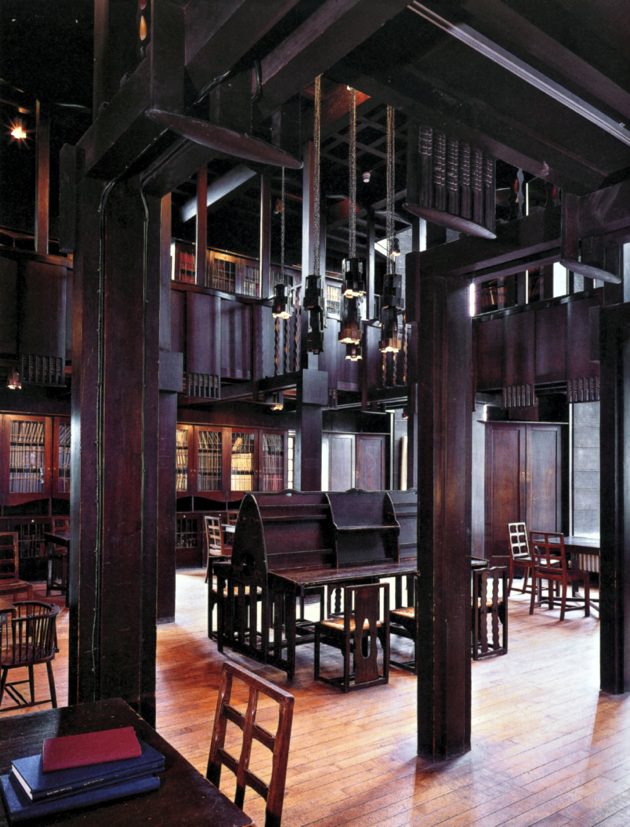

Mackintosh’s masterwork, of course, is the Glasgow School of Art (built in two increments, the first executed in 1897–1899) and Macaulay devotes particular attention to its celebrated library (1907–1909). In his most novel and important interpretation, he maintains that the library is in fact an encoded manifestation of the Tree of Knowledge. The verticality of this soaring reading room, illuminated by three 25-foot-high west-facing oriel windows to maximize the city’s scant winter light, is enhanced by long, root-like hanging lamps and trunk-like columns surmounted by a stylized dome that suggests the crown of a towering tree.

Sadly, the building’s universal renown has not protected it from the expansion pressures that many art institutions now face. The most favorable thing one can say about the overrated American architect Steven Holl’s $80-million design for an annex to the Glasgow School of Art is that it would be built across the street from Mackintosh’s original rather than next to it. However, not only would Holl’s cubist, white-clad structure be wholly at odds with the city’s architectural ethos and tonalities, but ambient light from the new building’s vast windows and reflective façade would completely ruin the subtle illumination that makes the neighboring landmark even more arresting after dark.

Advertisement

Despite the expensive-seeming aura of Mackintosh’s public and private interior ensembles (which invariably included his hallmark high-backed chairs and decorative panels by his wife), he favored humble components. Look closely and you will find that enamel paint conceals the grain of cheap wood; brown wrapping-paper is elevated to a wall covering; stenciled muslin or burlap become hangings; and loose arrangements of brambles and weeds fill beaten copper containers. He believed in the uniqueness of every object almost as a moral obligation, and refused to recycle his furniture schemes for new commissions. Everything had to be reconceived from scratch because, as a friend recollected, “Mackintosh once asked me why he should design for my use an armchair like that of someone else.”

When Mackintosh wrote to Josef Hoffmann in 1903 to encourage the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), which the latter co-founded that year, he sounded like William Morris, the grand guru of the Arts and Crafts Movement, who famously exhorted, “Have nothing in your homes that you do not know to be useful and believe to be beautiful,” and insisted that good design was a birthright of all classes:

From the outset your aim must be that every object which you produce is made for a certain purpose and place … [A]ttack the factory-trade on its own ground, and the greatest work that can be achieved in this century, you can achieve it: namely the production of objects of use in magnificent form and at such a price that they lie within the buying range of the poorest.

Mackintosh could never fully achieve that high-minded goal himself. His building career was undermined and then halted by his acute alcoholism and the deep depression it exacerbated, which alienated him from colleagues and clients alike. Swiftly changing fashions made his unconventional designs look outmoded within a few years of his brief heyday. But in the improbable setting of grimy, industrial Glasgow he created radiant oases of extraordinary grace and refinement, wherein, as one contemporary admirer wrote, Mackintosh “raised the banner of beauty in this dense undergrowth of ugliness.”

James Macaulay, Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Life and Work (W.W. Norton, 2010)