I recently had the chance to see an extraordinary new exhibition space devoted to the arts of Islam. The collection included works in stone, metal, glass, ivory, and textile, as well as illuminated manuscripts, and spanned from Moorish Spain and Umayyad Syria to the Central Asian steppe and Safavid Iran; the pieces were mostly of a quality that might be worthy of any great world institution. Readers may at this point guess I am talking about the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s just-reopened Islamic galleries. Actually, I was visiting a museum in the tiny Persian Gulf nation of Qatar.

Like the new Met galleries, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the Qatari capital, attempts to provide a comprehensive view of its subject; the two museums even feature a number of nearly identical works — inlaid wood panels from Medieval Cairo; the Ferman, or signature, of Suleyman the Magnificent; carved marble acanthus capitals from 10th-century Cordoba; ceramic bowls from Nishapur in the uncannily modernist “black-on-white” style. But there the similarities end. Whereas the Met amassed objects like these over the course of more than a century, in Doha, the collection was built from scratch in less than a decade. For all its grandeur, it is as new as the artificial island the museum is sitting on.

In fact, the Museum of Islamic Art, which opened in 2008, is only the first of a series of colossal projects now being launched by Qatar’s Emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani, through the recently established Qatar Museums Authority. Last year, Qatar opened the Arab Museum of Modern Art, known as Mathaf (for “museum” in Arabic), which houses one of the most wide-ranging collections of twentieth-century Arab art in the region and features work by artists from such different lands as Iraq, Egypt, Syria, Morocco, Algeria, Lebanon, and Palestine. In one of its inaugural exhibitions, “Sajjil: A Century of Modern Art,” the museum showed how a distinct regional tradition of painting and sculpture emerged as Arab artists gradually adapted western currents and ideas to Middle Eastern idioms and experience. And the ground has just broken on the National Museum of Qatar, a structure so large and complex— arrayed across a 1.5 million-square-foot site, it is meant to evoke the interlocking petals of a native mineral formation called a desert rose—that the structural engineering alone will reportedly cost some half billion dollars. How did the rulers of this parched and featureless desert peninsula—a place that until recently was peripheral even to the politics and culture of the Middle East—come to take such a far-reaching interest in the aesthetic traditions of the Arab and Muslim world?

By now, the appeal of high-end museums and universities to newly flush Gulf countries is well-known. Like its close neighbor Abu Dhabi, which is now building satellites of the Louvre and the Guggenheim, Doha views having prestigious, western-caliber houses of culture as a prerequisite to placing itself among the ranks of world cities like Paris, Hong Kong, and New York. Hence the choice of I.M. Pei, who is neither Arab nor Muslim, to design the Museum of Islamic Art; and Jean Nouvel, who is of course French not Qatari, to design the National Museum.

But visiting Qatar, it’s also hard to avoid the sense that the country is intensely interested in writing a past for itself, even as the Qatari capital’s ultra-modern skyline emerges seemingly out of the sand. As you cross the pedestrian causeway to the Museum of Islamic Art, you are confronted with a series of old pearling ships. Moored along the waterfront and restored into mint condition, they self-consciously assert the country’s economic heritage (pearling was the mainstay of the economy before oil and gas) next to the social and religious heritage preserved in the museum. North of the capital, archaeologists have been digging up the buried remains of Al Zubara, an abandoned pearling village that was once the country’s main commercial center; for those who don’t want to make the trek, one of Doha’s most exclusive new hotels takes the form not of the usual waterfront midrise, but a series of traditional courtyard dwellings—a “recreated version of a Qatari village” that allows you to “experience the past today.”

Clearly the museums are central to these efforts. More and more, when Islamic masterpieces surface at auction, it is deep-pocketed Qataris who are placing the bids—with resources that not even the Met can match. (The original Qatari royal in charge of the Islamic Art Museum spent more than a billion dollars on art in just eight years, an amount that made even the Qatari government squirm and led the Emir, his cousin, to briefly arrest him in 2005.) Like their counterparts in China, who have been spending millions of dollars “buying back” Chinese antiquities that have migrated to the west, Qatar’s rulers have come to view the artistic traditions of their own region as a crucial part of their national story. And by concentrating on the art of the Middle East (rather than, say, Impressionists or Old Masters), they can reclaim for the Arab world the kind of material heritage—and the presentation of that heritage—that has long been the preserve of the West.

Advertisement

But why Qatar? Sparsely populated until the late eighteenth century and lacking any urban development until the 1950s, the country seems an unlikely custodian for Islamic civilization. Unlike Iraq, it cannot look back to Abbasid caliphs whose glittering courts inspired the Arabian Nights. Qatar doesn’t have grand mosque complexes or other major Islamic architecture; nor is it known—as Iznik is for tiles or Kashan for textiles—for a particular aesthetic style or material.

Yet that may be precisely the point. In the newly published catalog to the Arab modern museum’s “Sajjil” exhibition, the curators make no bones about Qatar’s conscious appropriation of Arab and Islamic heritage, which they say is “important…for the country’s constructed image and history.” Given Qatar’s meager national history, its rulers have discovered a strategic opportunity to redefine the country in a way that preserves its existing order, even as it modernizes as breakneck speed. (One outcome of this paradoxical effort has been the government’s bold support for popular revolts in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya while it quietly works to shore up the Gulf monarchies closer to home.) And what better way to address these apparently conflicting goals than through museums—institutions that can be modern and conservative at the same time?

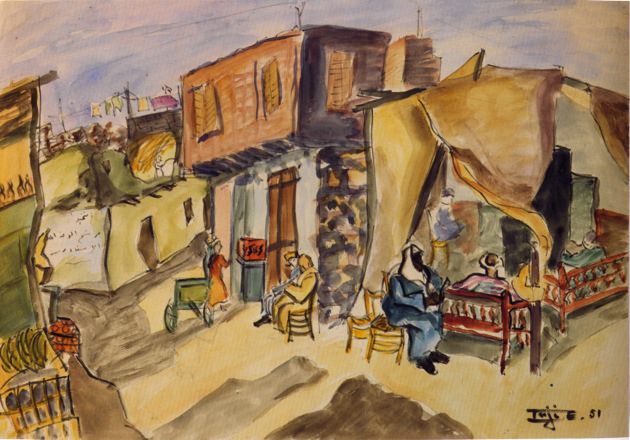

Consider the Museum of Islamic Art and the Arab Museum of Modern Art: The Islamic museum asserts Qatar’s status as a leading member of the Muslim community of states, reminding us of its Wahhabi heritage, its close ties to Saudi Arabia and the holy centers of the Muslim faith, and its deep roots in the cultural traditions of the whole Middle East. The Arab modern museum, on the other hand, shows off (to the elite international audience that will be drawn to such a venue) Qatar’s readiness to embrace the region’s vanguard. Assembled with great care by a collector who is close to the ruling family, the permanent collection includes work by early Arab revolutionaries like the Egyptian feminist Inji Efflatoun, who was imprisoned by Nasser, and by a group of Iraqi artists who decamped to Doha in the 1990s to escape Saddam’s Iraq. It also has commissioned large-scale installations, including Palestinian artist Khalil Rabah’s unsettling model of an aircraft carrier shaped like the Gaza strip that doubles as a tomato and strawberry farm. This is despite the fact that Qatar has hardly any tradition of politically-engaged art of its own.

There even seems to be a provocative self-awareness—or at least a nod to critics— about the presence of this art in a hereditary emirate in which the population has few political rights: one of the more striking works in the Mathaf collection, for example, is a sculpture from the 1960s by the Egyptian artist Taheya Halim called The Pyramid of Civilization, Symbolism Through Ants. A two-meter high, gold colored pyramid covered with little insects, it is a powerful commentary on the subjection of the working classes—who continue to build the ‘pyramids’ of modern Arab civilization. And while it was aimed at the tyrannies of an earlier moment in recent history, it cannot but resonate with the situation of Qatar today, whose proliferation of skyscrapers, luxury malls, artificial islands, stadiums, and museums have been built on the backs of more than a million low-paid migrant workers. The shiny new city caters to wealthy Qataris, foreign expatriates, and tourists; those who are building it are generally shunned.

All of which suggests a remarkably sophisticated exercise at nation building through art. Still, during my stay in Doha this summer, I often found myself alone, or nearly alone, at the museums I visited. Nor was it quite clear how these immaculate collections might connect with some distinctly Qatari tradition or sensibility. The ultimate test may be the National Museum which, unlike the Islamic and modern Arab museums, will have an explicitly Qatari emphasis and cannot rely on the contributions of other parts of the Arab world. Though there has long been a royal collection featuring some archeological finds and exhibits relating to pearling and historic village life, the country offers little material to fill out a national story.

Advertisement

Faced with this challenge, Nouvel, the architect, has devised an ingenious solution: many of the walls of the building will be engineered to function as giant LCD screens, on which can be projected images of the desert or of whatever visual material related to the country the curators want to use. When I asked her about this, Peggy Loar, an American who is now director of the Qatar National Museum, told me that one area of the galleries may project a live feed from the Qatari-government-backed news channel Al Jazeera—arguably the country’s most recognizable brand.

To give shape to a more fully-fledged idea of national culture, Qatar’s new museums will have to embark on the kind of research that gets beyond beautiful buildings and objects to connect with people and how they view themselves. For the moment, there is a risk that places like the Museum of Islamic Art—which still lacks a true curatorial department—will do far more to dazzle visitors than to bring new light on the country’s traditions. But as Qatar increasingly seeks to address a world audience—whether through Al Jazeera, or sporting events, or high culture—maybe it doesn’t ultimately matter. As with Nouvel’s videographic walls, Qatar’s leaders seem to have discovered that the cultural institutions of their cash-rich country can serve as a congenial series of screens, on which to project whatever images they find most suggestive of the nation they want to create.