James Nares’s Street, an engrossing and celebratory hour-long, oversized video projection of life in New York City, is a monument to evanescence. Now installed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 27, the work was fashioned from sixteen hours of material, recorded in six-second bursts from a vehicle moving through city streets at a rate of thirty miles per hour. Nares used a high-speed Phantom camera capable of filming up to one thousand frames per second; this footage was then slowed down by a factor of twenty so that each six-second pan was distended to two minutes, transforming the artist’s urban safari into a smooth, continuous glacial crawl.

The molasses-paced tour opens in Times Square and, occasionally revisiting the midtown area, goes through Harlem, Chelsea, and parts of the Bronx, with extended crosstown trips to transverse busy 125th, 34th, and 14th streets, accompanied by Sonic Youth guitarist Thurston Moore’s unamplified twelve-string vamping. (The music is more or less ambient; however for a live projection at the Met on April 15, Moore and a percussionist performed a more varied and assertively discordant piece that distracted from the images.)

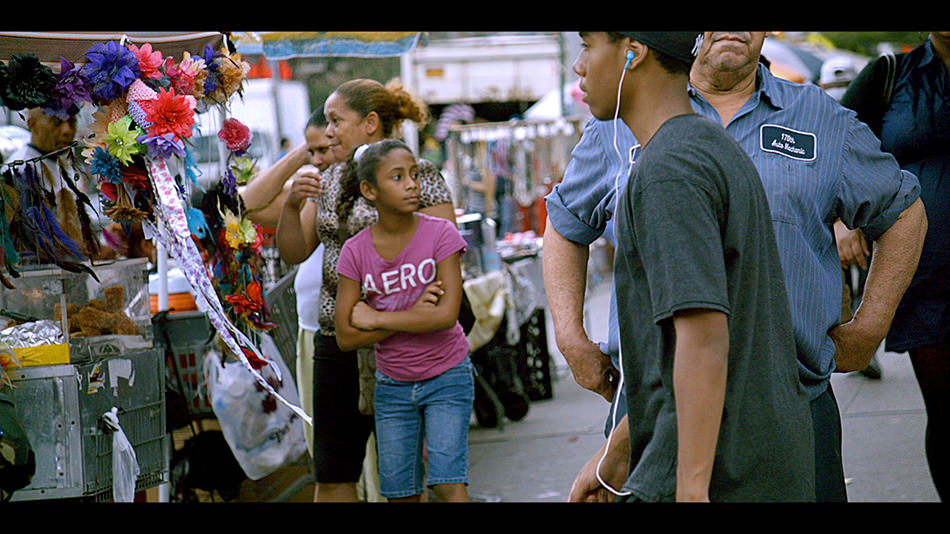

Most of Nares’s subjects are oblivious or indifferent to their documentation, although a few are hyper-alert. People point to things we cannot see or make hieroglyphic gestures that unfold too slowly to be decoded. Tourists take their own images and occasionally one catches a glimpse of the filmmaker’s silver SUV reflected in a storefront window. Kids clown, adults stare. The moments when someone locks eyes with the camera are always electric. Nothing may be more dramatic than the focused concentration of New Yorkers hailing a cab, but small sensations become thrilling events. Rain falls. A woman’s hair is caught in the breeze. A merchant demonstrating a child’s toy produces a trail of soap bubbles. A low-flying pigeon comes in for a landing.

The moment-expanding, arrested-time effect has appeared in any number of Hollywood films, including Taxi Driver and virtually every feature made by action-movie director Michael Bay. Here, however, congealed temporality is the main point: Street is a motion picture predicated on two types of motion. The first is the inexorable forward movement of the filmmaker’s car, proceeding at a constant speed although periodically—and almost invisibly—reversing direction. The second is provided by the wildly contrapuntal activities of the people on camera. Nares is best known for paintings made with a single brush stroke. Street, which is composed of thirty or more smoothly conjoined separate shots, is a comparable gesture.

Transforming the city into a kind of mass choreography, Street may suggest an updated version of Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 Koyaanisqatsi, the only non-narrative avant-garde film to ever play Radio City Music Hall; actually, it is quite the opposite. Where Koyaanisqatsi is essentially a jeremiad, using pixilation as well as slow motion, along with Olympian camera angles and an overwrought Philip Glass score, to portray urban life as an unnatural catastrophe, Street, shot at eye-level and deliberately paced, is more investigation than judgment. There is much that can be gleaned from it regarding New York’s social structure but, far from condemning the metropolis, Street revels in its diverse types, feasting on what the sociologist Georg Simmel described 110 years ago as the psychological conditions of modern urban existence: “the rapid crowding of changing images, the sharp discontinuity in the grasp of a single glance, and the unexpectedness of onrushing impressions.” (In taking the metropolis as a fact of nature, Street is more akin to the unprepossessing but conceptually rigorous films, sometimes predicated on a simple effect like superimposition that the artist Ernie Gehr has been making since the late 1960s.)

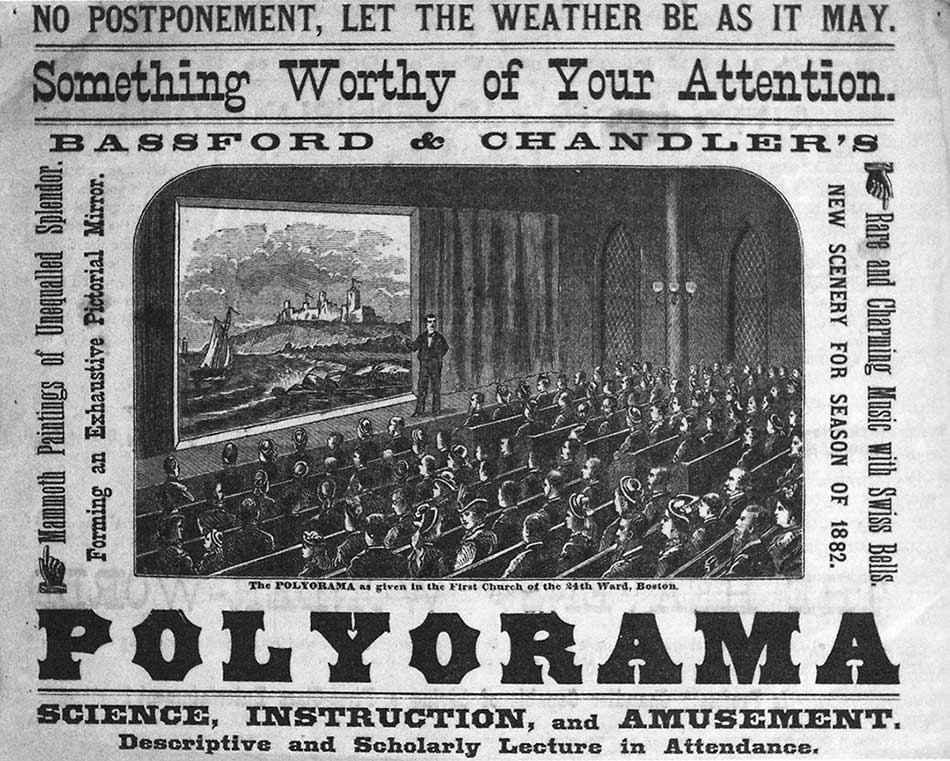

Indeed, Street may be considered a descendent of the moving panoramas—theatrical spectacles that flourished, mainly in England, France, and the United States, from the late 1700s into the early twentieth century. Initially gigantic painted vistas, often of urban prospects, battlefields, or seascapes, these evolved into massive scrolls that would be unspooled in front of viewers over time. As it happens, I have been reading Illusions in Motion, media archaeologist Erkki Huhtamo’s densely-footnoted new excavation of this tradition. Not surprisingly, the spectacles, which coincided with the rapid growth of cities themselves, were largely anti-urban, concerned almost exclusively with majestic landscapes and natural phenomena like the Mississippi River, the straits of the Bosphorus, or the Alps. Yet they offered contemporary journalists a readymade metaphor for the feel of city life. “The metropolitan experience suggested a moving panoramic canvas, even if the sight did not match the subject matter of most actual panoramas,” Huhtamo writes.

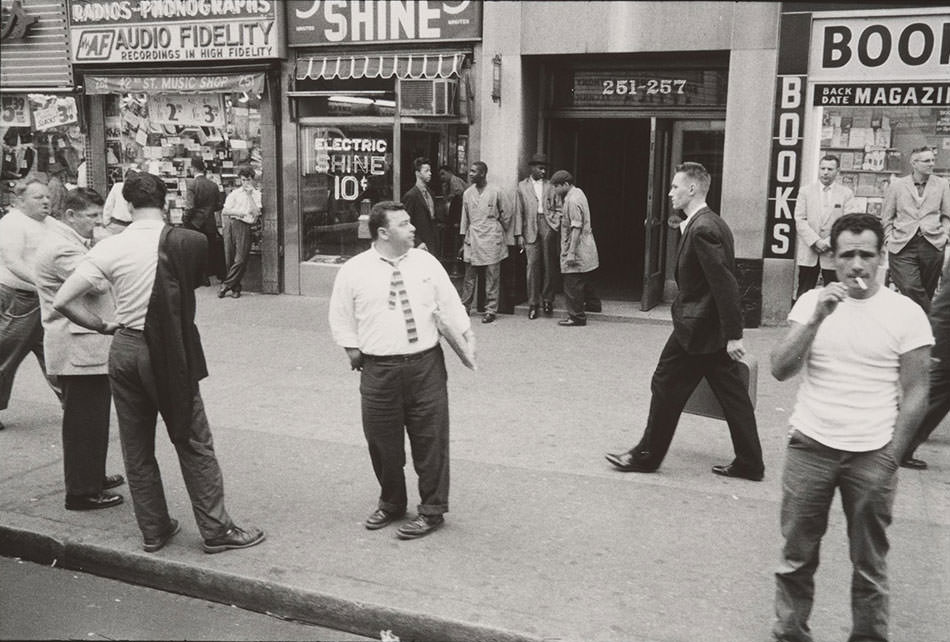

Nares himself cites the brief urban actualités produced at the turn of the last century by the Lumière brothers and Thomas Edison as his inspiration while providing, in the Met’s exhibition of Street, a broader setting for the work with a selection of objects from the museum’s collection. These include street photographs by both anonymous and celebrated photographers like Robert Frank (as well as Berenice Abbott’s 1929 “New York Scrapbook” and a collection of flattened bottle caps scraped off the pavement by Walker Evans), exuberant urban scene paintings by Félix Vallotton and Philip Guston, a Goya beggar, one of Franz Messerschmidt’s grimacing busts, late nineteenth-century motion studies by Étienne-Jules Marey and Thomas Eakins, a sixteenth-century Chinese scroll, a five-thousand-year-old Mesopotamian figurine of a striding man, and a Roman fragment of a sandal-shod foot.

Advertisement

The obvious point is that Street itself is a relic. It cannot be coincidental that the footage was shot around the tenth anniversary of 9/11. Nares maintains that Street is intended “to give the dreamlike impression of floating through a city full of people frozen in time, caught Pompeii-like, at a particular moment of thought, expression, or activity.” The notion of the current imperium as future ruin is evidently something that the British-born artist brought with him to New York; back in the day of punk rock gestures, Nares directed a number of East Village musicians and personalities in a Super-8 burlesque entitled Rome ’78, which memorably featured the spindly toga-clad painter David McDermott tirelessly ranting “I am God!” on the steps of Grant’s Tomb. Nares’s new-minted antiquity preserves the New York City of September 2011, captures those intensified moments of metropolitan life that, save in the midst of catastrophe, we usually take for granted.

The exhibition Street is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 27. Erkki Huhtamo’s Illusions in Motion: Media Archeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles, was recently published by MIT Press.