Over the four decades since the Pritzker Architecture Prize was founded, its jury has taken remarkably varied approaches to the accolade. At times it has been a lifetime achievement award, as with the elder statesmen Luis Barragán (1980) and Kenzo Tange (1987). The Pritzker has also served as a late-life consolation prize, as when it went to the eighty-five-year-old Jørn Utzon (2003) three decades after the completion of his only major work, the celebrated Sydney Opera House.

More recently the jury has sent some thinly veiled political messages—for instance, choosing the Baghdad-born Zaha Hadid (2004) immediately following the US-led war in Iraq. And two years after the prize went to Hangzhou-based, tradition-minded modernist Wang Shu (2012) in what one writer called “a radical critique of Chinese urbanization,” China’s president, Xi Jinping, famously decreed “No more weird architecture” in his domain.

The Pritzker panel (which has changed when the terms of the chairmen and jurors expire) has also been quite capable of surprises, including what might be called premature adulation. It has named three fifty-year-olds—Richard Meier (1984), Hans Hollein (1985), and Christian de Portzamparc (1994)—whose subsequent works have seemed unworthy of the profession’s highest honor. In other years, the “Who he?” factor has led some to speculate whether geographical distribution to counterbalance the preponderance of eight American and seven Japanese laureates led to the naming of such little-known figures as the German Gottfried Böhm (1986), the Norwegian Sverre Fehn (1997), the Brazilian Paulo Mendes da Rocha (2006), and the Portuguese Eduardo Souto de Moura (2011).

But this year’s award, which will be presented in Miami next week, has taken an unprecedented twist. On March 9, two months after being informed confidentially that he’d been named the fortieth Pritzker recipient, the German architect and engineer Frei Otto died. The eighty-nine-year-old Otto made it just under the wire, as the Pritzker’s rather nebulous and occasionally malleable bylaws stipulate that the prize cannot be bestowed posthumously.

By reaching into the back catalog of twentieth-century architecture, the jury’s decision recalls the joint award of the 1988 prize to Oscar Niemeyer and Gordon Bunshaft, who were then eighty and seventy-nine respectively. Though long past their creative prime, they personified a meridian moment of High Modernism that implicitly made Postmodernism, then at its peak, appear shallow and trendy, another example of the Pritzker as critical commentary.

Yet even architectural devotees could be forgiven for thinking that Otto had died years ago, in that he had executed few designs since the turn of the millennium. In one of his final major efforts, he collaborated with Shigeru Ban (last year’s Pritzker winner) on the Japanese pavilion for Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany: an oblong, clear-span exhibition hall overarched by a biomorphic latticed roof that swelled upward in three equal segments. Otto’s major contribution was the modern tensile tent made from synthetic materials reinforced with metal mesh, unlike all-fabric antecedents, which he perfected in the 1950s and brought to worldwide attention in the late 1960s and early 1970s; ironically, it has since become so pervasive that it is perceived as a generic development rather than the invention of one person.

Frei Paul Otto was born in 1925 and grew up in Berlin. His uncommon first name—which means “free” in German—reflected the values of his idealistic parents, members of the Deutscher Werkbund, which promoted public education in good design and collaboration between craftsmen and industry. Otto developed an early passion for sail gliding, which shaped his fascination for lightweight structures. Soon after he began his studies in 1943 at what is now the Technical University of Berlin, he was conscripted into the Luftwaffe. Captured by the Allies, he was incarcerated for two years, during which he served as a prison-camp architect, a position that forced him to address the most basic function of architecture—shelter.

After the war Otto completed his education and confronted the central challenge of his generation of German architects: how to create large-scale buildings that avoided the taint of Nazi design. Otto’s familiarity with aeronautic engineering led him to devise ultra-lightweight forms that derived from thin-membrane airplane parts made from reinforced fabric, the antithesis of the ponderous, stone-clad Stripped Classicism favored by Hitler. One of his earliest public successes was the gossamer-light dance pavilion he designed in 1957 for the Federal Garden Exhibition in Cologne, a five-peaked, mast-supported, white-fabric canopy in the shape of an exotic bloom that evoked the botanical theme of the event.

In contrast to many of his contemporaries, Otto departed from the neo-primitive Brutalist aesthetic favored by Le Corbusier after World War II and was much more like the eccentric Catalan master Antoni Gaudí, whose extensive research into naturally occurring structures was likewise the basis for startlingly new architectural forms that look organic but possess the strength of industrial elements. Frei took his cues from phenomena such as the way soap film spans a gap with maximum efficiency, or the extraordinary tensile strength displayed by fragile looking spiderwebs.

Advertisement

He felt a special kinship with his thirty-years-older American counterpart R. Buckminster Fuller, father of the geodesic dome, the other great structural innovation that emerged at midcentury. The self-aggrandizing fabulist Fuller and the self-effacing moralist Otto could not have been more different personally, but their ingenious designs shared similar limitations. Despite being widely promoted as panaceas for a host of architectural tasks, both Fuller’s dome and Otto’s tent were essentially roofing systems, and for all the economy with which they could cover an interior, subdividing those volumes for specific functional purposes was much trickier.

The curvature of a geodesic structure renders space almost useless around its inner periphery as it meets the ground, while its center is often higher than required except for structural reasons. Similarly, a large tensile tent must be suspended from vertical supports that can disrupt an internal expanse, and the problem of how the roof turns into a wall was often inadequately resolved.

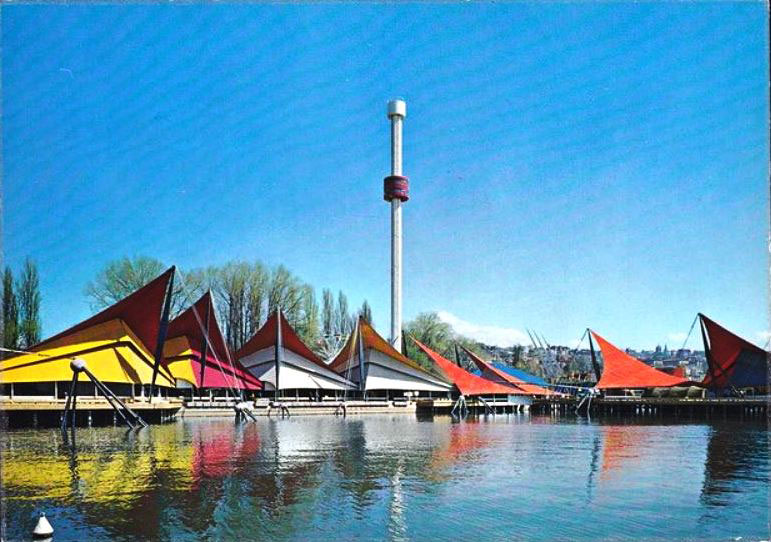

Then, after a decade of designing increasingly large, more complex tents for trade shows and outdoor stages in several German and Swiss cities, Otto received two high-profile, career-changing commissions. The West German government asked him to design its pavilion at Expo 67 (the Montreal world’s fair) and a vast multi-structure complex for the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Together, Otto’s eye-catching experiments made his international reputation, as well as that of his engineering associate Jörg Schlaich. What appears even more impressive in hindsight is that until the early 1970s Otto created his structures without the benefit of today’s sophisticated software, and instead worked out the complicated dynamics of each effort with costly, labor-intensive study models.

I was in Munich during the 1972 games—admittedly to see a festival performance of Tristan und Isolde rather than the sporting events—and I still recall the thrilling effect of dappled sunlight that filtered through the translucent fabric overhead as one walked through the curving sequence of exhibition and refreshment tents that snaked around the Olympic Stadium. (For this commission, Schlaich invented a new set of computer analysis tools to execute Otto’s design, a historic first in the profession.)

The work of Frank Gehry has shown how far such programming tools can bring the building art, in his audacious recasting of architecture from rectilinear convention to freeform exuberance. A host of precursors have been suggested, from the German Expressionist Hermann Finsterlin to Utzon. Yet Otto—whose use of aeronautic prototypes is paralleled by Gehry’s brilliant architectural adaptation of the CATIA software initially intended for the design of irregularly shaped airplane components—now seems a more convincing forerunner. However the connection between these indisputable architectural originals is reckoned, there can be no doubt that Frei Otto helped lift his homeland out of the darkest period in its history through marvelously wrought designs that conveyed not only stunning technical finesse but, more importantly, a spiritual lightness of being.