Julie Taymor declared recently that A Midsummer Night’s Dream is “unfilmable.” The remark was intended not to disparage her own just-released movie version of the play, but to define just what it is: not a film in the same sense as her earlier Titus (2000) and The Tempest (2010) but a record of the stage production with which she opened Theater for a New Audience’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 2013. Filmed theater, then, in its purest form but, as she has been careful to point out, produced with unusual thoroughness, deploying multiple cameras over multiple performances, and allowing for opportunities to move among the actors on stage with a Steadicam: in that sense as much a “true film” as some of the technically impeded early talkies in which two or three immobile cameras filmed the same scene from different angles simultaneously to allow for rudimentary cross-cutting. The main difference with Taymor is that we see the audience that surrounds the stage on three sides.

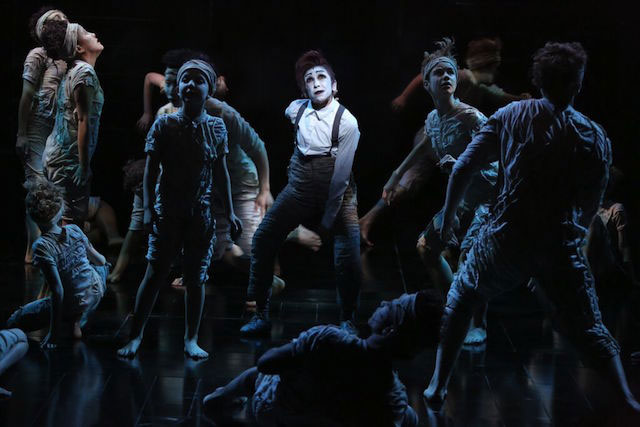

The project was undertaken because the stage mounting was too elaborate and too specifically keyed to the dimensions and capabilities of the Polonsky’s flexible courtyard-style stage, to be recreated elsewhere. I did not see the production on stage, but the film makes clear what exuberant use Taymor made of the Polonksy theater’s dimensions—with its vaulting space above and its multiple points of entry from trapdoors and aisles. This is true from the moment Kathryn Hunter as Puck—but more suggestive at this point of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland—clambers into a vast storybook bed that proceeds to rise into the sky. Cascades of visual wonders duly come to pass: an immense white sheet billowing into view, Oberon (David Harewood) descending out of the firmament, Titania (Tina Benko) sinking out of sight within the folds of the sheet; opalescent floral projections making visible the “little western flower” with which Oberon proceeds to work love mischief; hordes of wild children (the “Rude Elementals” who in Taymor’s vision stand in for anything more recognizably fairy-like) brandishing poles in shifting formation to make woodland mazes. The effects dazzle without any attempt to disguise their artifice, but rather with the bravado of acrobatic feats under the big top.

Taymor’s film reveals more of the spectacle than any one spectator at the theater could have seen. Nonetheless a filmed version of a stage production cannot quite capture the sense of being there, even if the wizards currently developing the science of virtual reality no doubt are conceiving ways to eliminate the distinction. By an odd perceptual paradox, even an aggressively anti-naturalistic film like Taymor’s Titus, with its mixing of eras and interpolation of visualized allegories, imposes itself as a world to which we react as if it were real, while all the detail with which her production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is documented cannot fully persuade us that we are in the theater watching it. At the same time, if we were in the theater we would surely succumb to the theatrical illusion and take Oberon and Titania and Puck for actual beings; filmed, they are actors assuming roles. We may admire them (Harewood and Benko are indeed admirable, and Hunter is so powerful in her blend of restless infant ferocity and the ancient wisdom of a primeval urchin that she makes Puck the play’s central force field) but we study them at a certain remove.

Taymor’s sense of the play’s unfilmability—and neither of the versions I’ve seen, including the often gorgeous Max Reinhardt pageant, really suggests otherwise—has to do with Midsummer’s essential theatricality. Cinematic art direction and special effects, however cunning, cannot adequately substitute for the very different kind of magic that actors can create out of the tension of being live on stage. Since the play—presumed to have been first performed as a masque for a marriage celebration—unfolds like a ritual, perhaps it demands a community of physically present onlookers for the ritual to be accomplished. The first word of Shakespeare’s script is “now,” and it feels like a signal for an action to be performed in real time.

The audience is part of the play, and our response to being surprised and played upon by the successive gags, spells, and metamorphoses an indispensable element of the proceedings. In live performance, no matter how amateurish the circumstances, I have never seen it fail to produce a sense of unexpected gratification at having emerged in one piece after being, like Bottom, “translated.” Everything is restored, only curiously changed, shot through with a lingering strangeness: “Are you sure / That we are awake? It seems to me / That yet we sleep, we dream.” Apprehended at second hand onscreen, the transubstantiation loses some of its force.

Advertisement

Occasionally I’ve wondered what place A Midsummer Night’s Dream would occupy in our culture if by some chance it were the only work of Shakespeare’s to have survived. A singular and revered position, no doubt, and surrounded with mystery: what sort of otherwise unknown writer might have created such a play? As it is, the mystery of Midsummer Night gets bound up in the larger mystery of Shakespeare. Yet it is an anomaly, distinct from anything he wrote before or after, a world to itself with its own rules and its own moods. It would be presumptuous to describe it as infused with a deeply grounded sense of happiness and human community—or at least of the yearning for happiness and community—since it would be equally easy to demonstrate, if one cared to, that the play provides, between the lines and by overt farcical illustration, the materials for a demolition of any durable prospect of such harmony.

At any rate it has reliably been the cause of such happiness in others. Steeped in darkness, conjuring at the outset images of natural disaster, the unsettling of climate by the sexual discord between primal entities, set in the heart of a bewildering forest, and playing on every sort of fear and jealousy and vengefulness and maddening deception, Midsummer Night possesses a singular power of keeping darkness at bay as if for all time, that is to say at least until the epilogue is over. Within the play’s limits, the theatrical space is secured as a zone at once of freedom and erotic wish fulfillment. The marriage that is consummated is of high and low, ethereal and animal, substantial and shadowy. The whole performance constitutes a protective charm, with the final safeguard of Puck’s last affirmation that in any event “you have but slumber’d here” and the whole thing will now dissolve like a dream.

The musicality of the play’s proportions, the uncannily precise exposition making each step in the process appear inevitable, survives nearly any approach, from the nasty-edged punkishness of a Nineties production by the Royal Shakespeare Company to the dry disenchantment of Jonathan Miller’s late Nineties staging at the Almeida in London. Taymor aims at a maximum of collective celebration, the chaotic looseness of a wedding party. The film’s advertising copy promises “the magic of love, drugs, and midnight madness,” and the mood is determinedly hilarious, sexy, and wild with the energies of children allowed to run rampant. The forest here is precisely the domain of children, although they turn up again in the last act decked out properly for a wedding.

We are definitely outside of history. Accents, like eras, are all over the place. Bottom and the rude mechanicals are multi-ethnic New York, which works very well except when it starts to seem like fighting against the text, if not jettisoning it. Giving Peter Quince an easy laugh by saying “oh, shit” in the middle of the fifth act doesn’t really add much; but wedding parties are wedding parties, and Max Casella as Bottom sustains an edge of wise-guy cockiness that is as funny and finally as deeply sympathetic as it needs to be. His transition from the “how lucky can a guy get” satisfaction in the midst of his liaison with Titania (played by Tina Benko with reckless all-out abandon) to the wry deflation of the morning after is beautifully exact.

The play’s general climate of unsettled lust, playing out chiefly in the successive confusions of affection among the two pairs of Athenian lovers under the influence of Oberon’s flower, is accented at every possible point, with Taymor never missing a chance to bring forward the passing notes of threatened rape (with Demetrius unmasked as ominous frat boy) and sexual humiliation. Lysander and Demetrius remain, as always, nothing but surfaces by which the shifting vagaries of male desire can be comically surveyed, while the buried childhood antipathies of Helena and Hermia start up with their usual irresistible force. Since their quarrel is one of the most reliably funny scenes Shakespeare wrote, it does seem unnecessary to have turned it into a free-for-all pillow fight. The genuinely menacing edge of the confrontation dissipates into a mere display of physical energy, like a musical number from some forgotten beach movie.

At times it seems as if the production has every virtue except austerity. Such is its explosive pitch that it cannot permit itself much in the way of pauses or silence once things get into full swing. The speech rhythms aim more at meaning and humor than at music, so some sublime passages get a little lost. (Hippolyta’s “I never heard / So musical a discord, such sweet thunder”—lines that add a grace note of solemnity to the moment when everyone wakes up at the end of the fourth act—is omitted altogether.) But it is all anchored splendidly by Harewood’s Oberon and Benko’s Titania, both suggesting forces not magical but natural at the most fundamental level; and unquestionably by Kathryn Hunter who so irresistibly dominates all, in constant movement as if maneuvering to hold the connecting strings of everything secretly in her grasp, a child empowered to realize in dream an ultimate freedom beyond the strictures of human law, and speaking the poetry not sonorously but in a commanding outcry compounded of mockery and wonder.

Advertisement

Taymor realizes one other touch toward the end of the play that shifts the accent in a revelatory way. After the three married couples have had their fun making side comments at the absurdities and ineptitudes of the mechanicals who perform the tragedy of Pyramus and Thisbe, after Bottom has indulgently rung all the changes of his death scene, Flute (Zachary Infante)—here a shy Latino—launches with a certain awkward uncertainty into her own last speech, at just the moment when the fun is wearing thin and the guests are hoping it will soon be over. As if surprising himself, the actor finds his way deeper into the part, and the spectators find themselves unexpectedly moved by what they were prepared to mock. It’s a delicate moment that vanishes quickly into the Balkan-sounding strains of a robust wedding dance.

Julie Taymor’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is now showing in select theaters in the US, the UK, Ireland, and Canada.