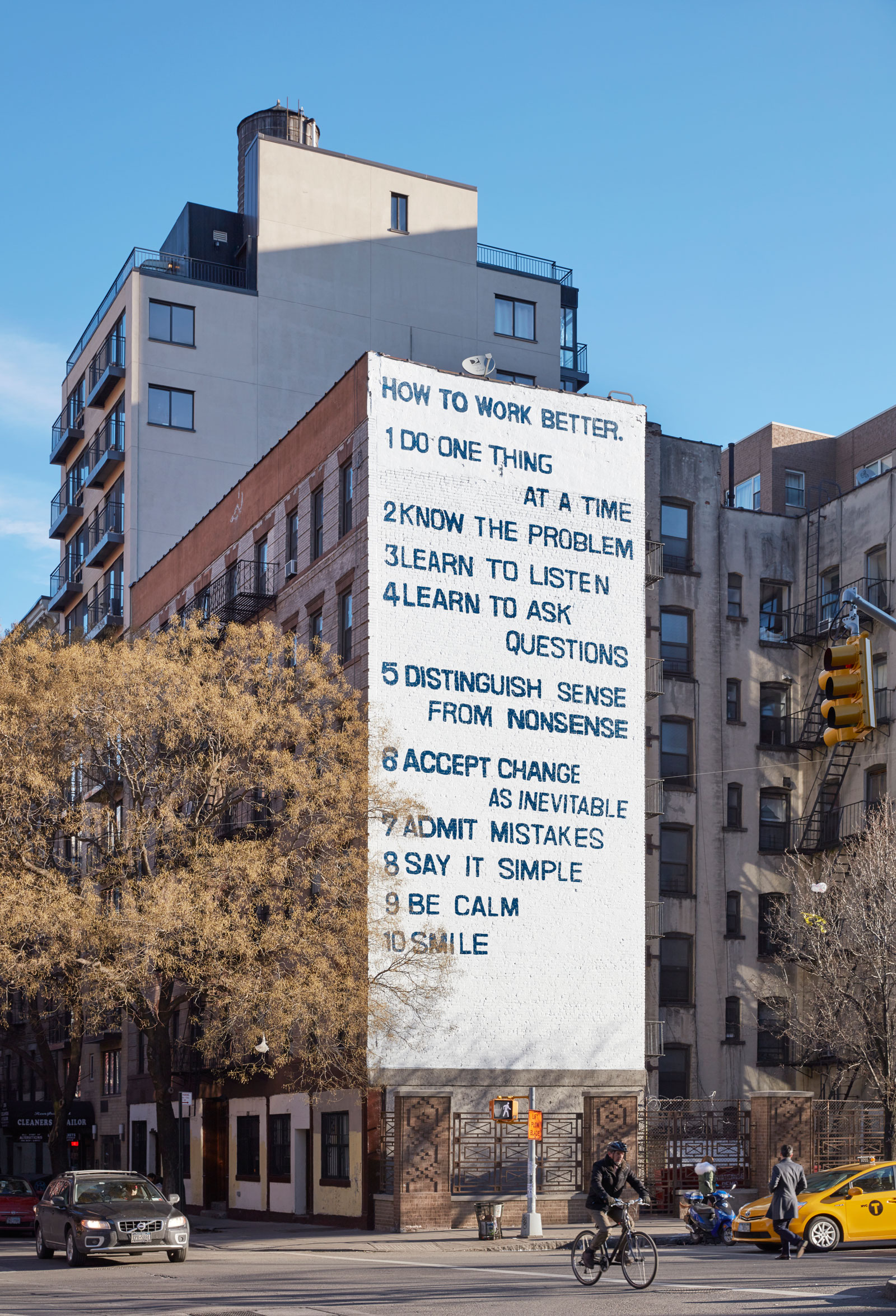

A few weeks ago, a six-story wall mural was unveiled on the corner of Houston and Mott Street in lower Manhattan. Against a white brick background, blue capital letters spell out ten motivational precepts on the theme of “How to Work Better”:

Do one thing at a time. Know the problem. Learn to listen. Learn to ask questions. Distinguish sense from nonsense. Accept change as inevitable. Admit mistakes. Say it simple. Be Calm. Smile.

Presumably, only a small percentage of the passing motorists and pedestrians know that the painted wall, which will stay in place until May, represents a collaboration between the Public Art Fund and the Guggenheim Museum, whose current show, also entitled “How to Work Better,” features the sculpture, photography and films of the Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss. And it’s likely that fewer still know that the artists (both from Zurich, who worked together, as Fischli/Weiss, from 1979 until Weiss’s death in 2012, based their mural, which originally appeared in Zurich in 1991, on a list of inspirational maxims they saw on a bulletin board in a ceramics factory in Thailand; they decided to see how different that helpful advice might seem, greatly magnified and displayed near a commuter rail line in a wealthy, heavily industrialized country. Since Weiss’s death, Fischli has worked on pieces that the two began together, including Haus, a model of a modernist office building that they completed in 1987 and hoped to install someday on Fifth Avenue, where it appears now, just outside the Guggenheim, for the length of the show.

The kind of humor captured in the How to Work Better mural—simultaneously playful and sincere, mingling the banal and the profound, attentive to the contradictions, ironies, and accidental beauties of the world—pervades the Guggenheim show, which was curated by Nancy Spector and Nat Trotman. Throughout the exhibition one can observe the influence of Dada and Surrealism, especially in those pieces that translate a familiar object (a hassock, a tree root, a closet) into an unfamiliar and disorienting medium (dark rubber or polyurethane). This artistic debt has been purged of the self-consciousness and self-seriousness so often present in the Surrealists’ work, possibly as a fortunate consequence of the equally formative legacy of the European punk scene, from which Fischli and Weiss emerged in the 1970s, when they began making fliers for a rock band they had formed together.

The two- and three-dimensional works, videos, and films manage to be rebellious without being strident, to be witty and cerebral without ever seeming pretentious or coy, to challenge traditional notions of what art is and can do, and to comment on the society in which we live without making us feel that their principal focus is provocation or attacking our politics and social order. (Slowly and almost subconsciously, we register the contrast between the “How to Work Better” mural and the gigantic commercial advertising billboards that line that stretch of Houston Street.) Perhaps because Fischli/Weiss’s work is collaborative, one never feels the obtrusive presence of an individual ego; and the fluidity with which they move from one medium to another is in itself a protest against any attempt to pigeonhole, narrowly commodify, or “brand” the artist. What unifies these disparate forms and genres is a highly particular spirit: questioning, curious, amused, and amusing, with an almost childlike delight in, and an animistic respect for, the mundane and the metaphysical.

Among the pieces on view is Fischli/Weiss’s first collaboration, “Sausage Series” (1979), a group of color photos of scenes constructed primarily from meat and other items—cigarette butts, toilet paper—that defy conventional notions of the “proper” material from which to make art, perhaps because it was constructed entirely from food and other humble items already available in Weiss’s apartment when the artists sequestered themselves there to make the photos. In At the Carpet Shop, a selection of sliced luncheon meats does a hilarious imitation of rugs stacked and luxuriantly arrayed for sale. In The Fashion Show, a procession of sausages, decked out in chic hats and accessories, and stylishly draped with processed meat, line up along a runway. Another photo series, “Equilibres (A Quiet Afternoon)” (1984-1986) portrays a succession of gravity-defying balancing acts involving vegetables, fruits, crockery, and kitchen utensils: a zucchini, a carrot, a pear, a spatula, a cup, a plate, a cheese grater, and a ladle. One can see, in this work, an early manifestation of Fischli/Weiss’s fascination with “the poetics of banality” and with the ways in which ordinary and familiar objects—arranged in an original way or seen from a different perspective—can seem wholly new and even astonishing.

Advertisement

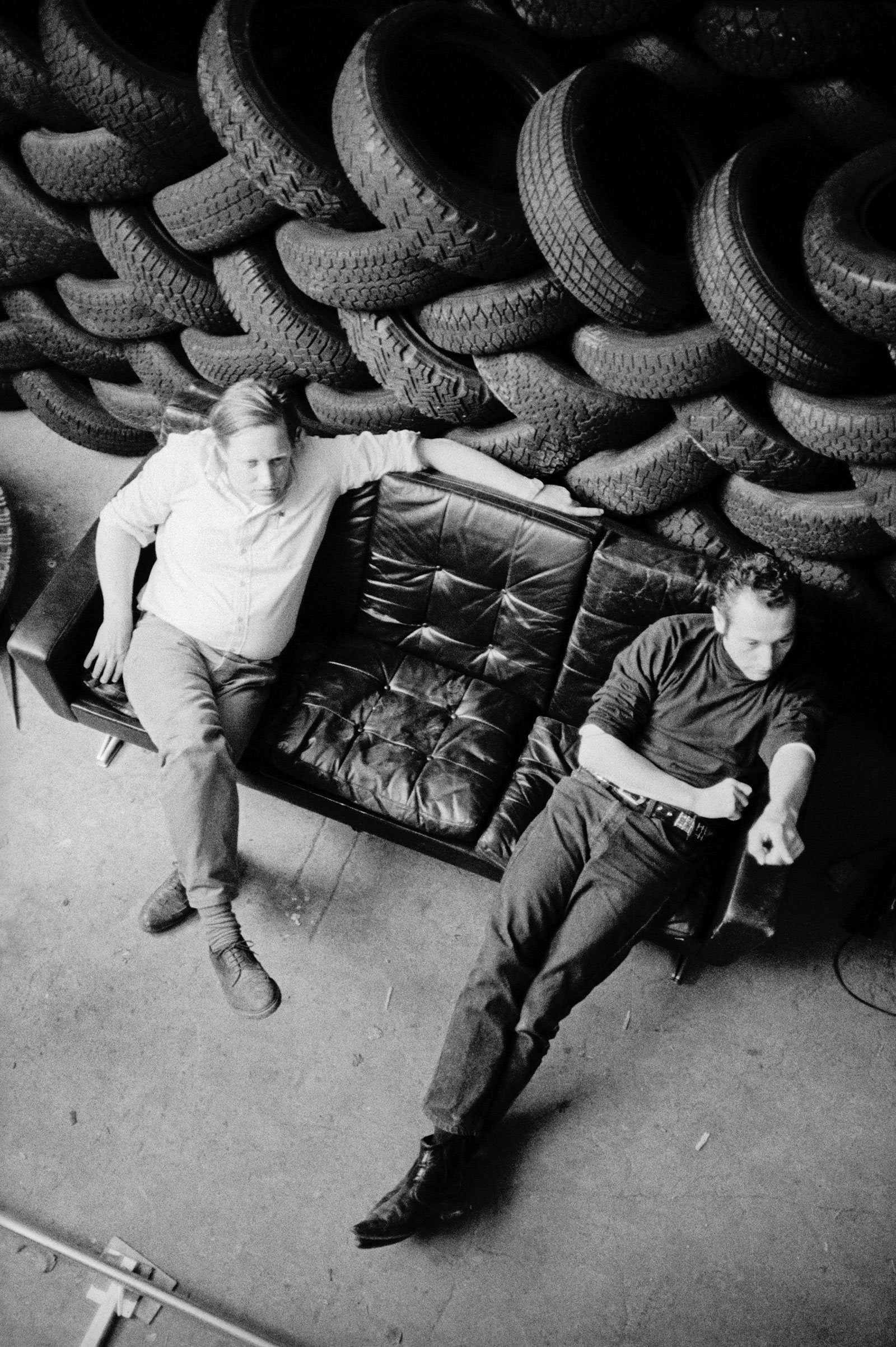

This field of inquiry (and the artists’ interest in the sensation of impending collapse created by the precariously balanced household items) led to one of their most famous works, The Way Things Go, (1987), a thirty-minute film. The camera records a series of objects (bottles, rubber tires, bulging trash bags, carts, plastic jugs, a roller skate, a tea kettle) arranged in a Rube Goldberg-esque contraption; set in motion, it causes a slow, continuous chain of collapses, tumbles, explosions and spills involving flammable and inflammable liquids, wooden boards, ladders, balloons and fireworks. The result is thrilling and oddly suspenseful as one waits for the next eruption, overflow, disintegration, or minor calamity—and it’s a great deal of fun. Seated on the bench beside me, several French children kept bursting into peals of laughter, and it occurred to me how rarely one hears anyone laugh out loud at a museum show of “serious” art.

Many of the hundreds of small, unfired clay sculptures in “Suddenly This Overview” (1981-present) look like the sort of thing that one of those children might have done in ceramics class. None of the sculptures—most of them displayed here on free-standing white plinths that visitors must navigate around—is much bigger than a shoe box; the figures and props are charming and evocative but simply, almost crudely, fashioned.

But the humor is less raucous than in The Way Things Go. And it’s less certain that kids would get the subtle, cerebral, and mysterious jokes that make up what the wall text describes (interestingly, if somewhat confusingly) as the artists’ attempt “to gather all the world’s knowledge in one place, using the imperfect systems of individual memory and personal choice rather than a rational or scientific approach.” Much of the fun is supplied by the ironic, clever, and frequently complex interplay between the miniature scenarios that the sculptures depict and their titles. A scene of a couple lying in bed is entitled Mr. and Mrs. Einstein Shortly after the Conception of Their Son, the Genius Albert. A single figure asleep is, we learn, Dreaming the First Dream Interpreted by Freud. One of two sculpted birds is An Attentive Listener. The range of subjects is encyclopedic: A Copy of Jack Kerouac’s Typewriter; Mick Jagger and Brian Jones Going Home Satisfied After Composing “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”; Dr. Hoffman on the First LSD Trip.

At the very top of the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp are several bays containing what initially appear to be raw materials and detritus from the artists’ studio: cigarette packs, beer cans, paint, a juice carton, cleaning supplies, cat food, sheetrock, plywood, furniture, tape, tools, and toothbrushes. At first we may think the artists have borrowed from their work space until you realize that they have replicated that space and the things that fill it; these objects have all been meticulously hand-carved and painted, using polyurethane foam. The trompe l’oeil has the effect of making the commonplace seem extraordinary, as do the video installations—Visible World, Airports, Venice Videos—that feature slide shows of the photos that Fischli/Weiss took on their travels: images of airport runways, of tourist attractions and landmarks such as the pyramids of Giza, and of many landscapes and cityscapes so unprepossessing that we might not give them a second look were we to find ourselves surrounded by them. If How to Work Better offers us upbeat, cheerful, vaguely absurd advice on how best to perform our daily tasks, these pieces—like much of what is on view at the Guggenheim—could go under the rubric of “how to see better”—more appreciatively, more inquisitively, and with a more open and frank delight in the modest wonders of daily life.

“Peter Fischli David Weiss: How to Work Better” is on view at the Guggenheim Museum through April 27.