With finalists in both parties questioning the legitimacy of the presidential nominating process, the 2016 election is once again presenting the country a hitherto unimagined spectacle. The rifts within both parties that were apparent last fall have now become canyon wide. Donald Trump and Republican Party officials waver between arguing and trying to make nice with each other—in case Trump becomes the party’s nominee. (Republican chairman Reince Priebus is reported to fear that Trump will fire him if he wins the nomination, which may not reflect national concerns.) Bernie Sanders’s complaint that the sequence of primaries has worked to his disadvantage has less legitimacy than Trump’s, but claiming that the rules of the nominating process as stacked against them has become part of both rebels’ arsenals.

In the New York primary on April 19, both Trump and Hillary Clinton broke a string of recent losses with sweeping victories. Trump captured over 60 percent of the Republican vote to John Kasich’s 25 percent and with Ted Cruz coming in third at 15 percent; while Clinton, at 58 percent to Sanders’s 42 percent, claimed almost as large a share of Democrats. The outcome put each victor on the path to winning their party’s nomination, but Clinton is in a safer place than Trump—largely because of the delegate and nominating rules that he decries.

The Republican nominating contest has been proceeding on two levels for some time: there are the voting results in the primaries and caucuses that have attracted most of the press and public attention; and then there is the only recently-noticed actual allocation of delegates, which in some states doesn’t appear to reflect what happened in the primaries and caucuses. The Republican front-runner had been largely flying by the seat of his pants, focused on building up victories through his rallies and free television appearances, and writing frequent messages on Twitter. His staff lacked experience in national politics. He’d been relying on his gut and his brain, and doing an impressive job of it. But in the past couple of weeks he recognized that that wasn’t enough.

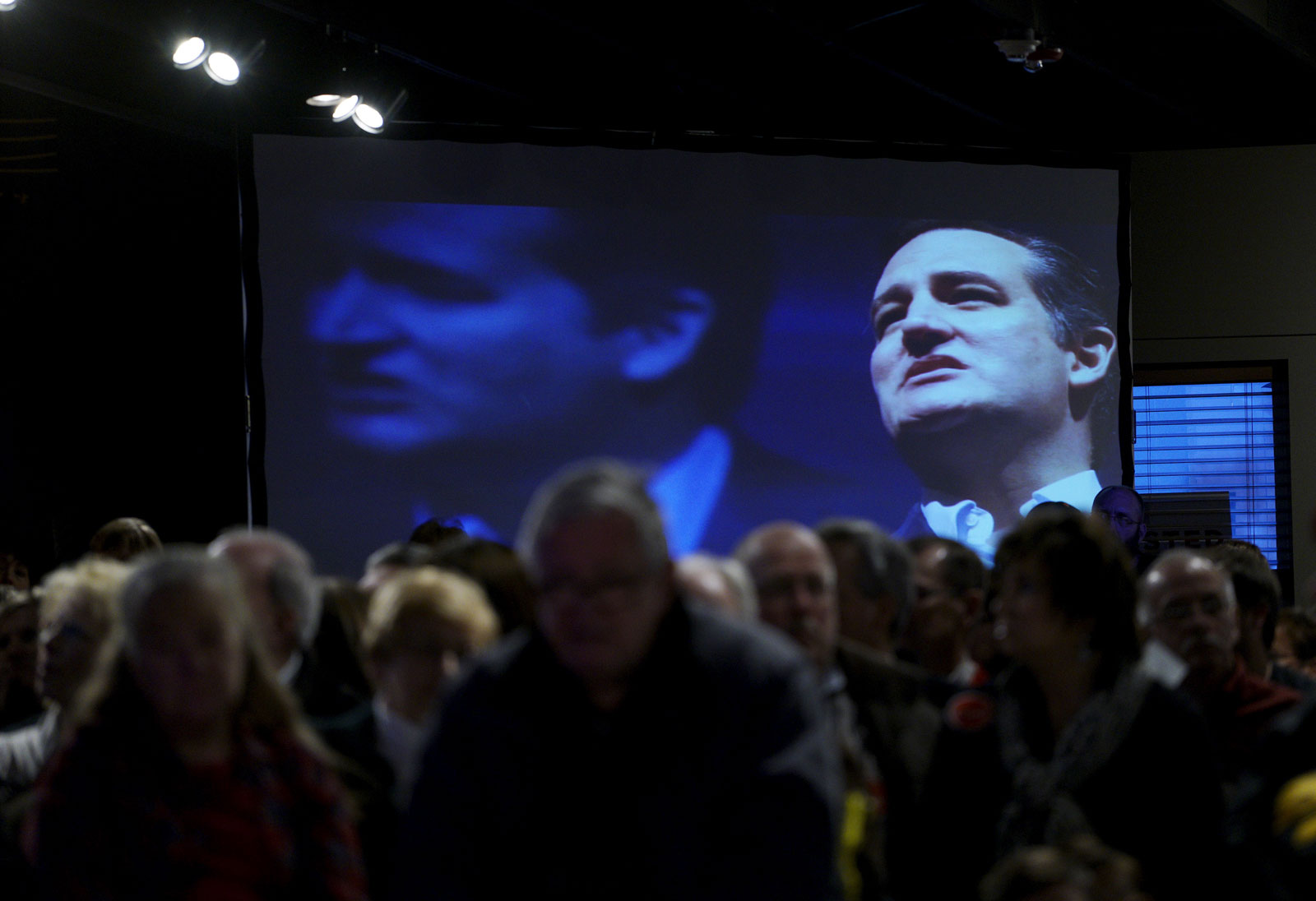

Despite his enormous success in the primaries, Trump had a big problem: neither he nor his small and isolated staff understood that he also needed to work the complicated Republican system of allocating delegates. Trump has to win the requisite 1,237 delegates, a majority, or come very close to that, before the balloting begins at the convention in Cleveland in July. The consensus is that if he doesn’t win on the first ballot at the convention, he’s finished. After the first ballot, the party’s very conservative base would then dominate the convention, and Trump isn’t the candidate of the party’s base. That would be the hyper-conservative Ted Cruz, senator from Texas—and Cruz has been successfully gaming the rules to pick up as many delegates as he could. While Cruz stands little chance of defeating Trump before the convention he may be able to prevent him from going to Cleveland with enough delegates to prevail.

Trump’s charge that delegates are being “stolen” from him is politically effective—it fits his self-characterization as the “outsider”—but it’s somewhat misleading. Ninety percent of the delegates are bound by their respective state laws to vote on the first ballot for the winner of the primary or caucus in their state—and that would favor Trump, who has run up numerous decisive victories. The issue of “stolen” delegates refers to what happens after the first ballot. Some states bind their delegates to the winner of their contests for one or two ballots—some may even be for three, but that’s rare. It’s actually the second-ballot vote, for which Cruz has been lining up the delegates, that Trump charges him with “stealing”—whether or not he’s aware of that.

Trump is dead right when he says the nominating system is “rigged.” The fundamental fact is that the Republican Party’s process for selecting its presidential candidate is controlled by the base. The Republican National Committee leaves the rules for delegate selection up to the states and territories, and many states, through obscure state executive committees, have adopted procedures that reward the candidate who’s closest to the base, the most active members, the ones who participate in party politics between elections—and these are the more conservative voters. The rules, then, favor a conservative candidate with strong organization at the local level. (By contrast, the Democratic party awards delegates in proportion to a candidate’s votes in the state contest.)

To take a major example of how the rules are rigged, a full 55 percent of the Republican delegates are selected through a two-tiered system: it starts with the voters expressing their preferences in a statewide primary or a caucus; but then the actual delegates to the national convention are chosen in a separate process that favors the base. In Louisiana, Trump defeated Cruz on March 5 by a margin of 41 to 38, but Cruz later recruited ten more delegates than Trump; Cruz also managed to collect five out of six of Louisiana’s allocated seats on the rules and platform committees. In Virginia, Trump came in first on March 1, with Marco Rubio second, and Cruz third; but Cruz has done better than Trump in the state’s process for choosing the delegates and is poised to sweep the state convention on April 30 that will choose the delegates to the national convention. Thus, though Virginia’s delegates will be bound to vote for Trump on the first ballot in Cleveland, they actually favor Cruz and would support him on a second ballot as well as on other issues during the convention.

Advertisement

The rules can be used against Trump in other important ways even if he has a sufficient number of delegates. Ben Ginsberg, a Washington lawyer and the reigning expert on Republican election rules, said in an interview, “Even if delegates are bound on the first ballot, they don’t have to support that candidate’s position on other matters including rules issues, credentials challenges, procedural floor votes, or the selection of a vice president.” That’s quite a lot that can go awry for the front-runner if he has a determined opponent.

There are other ways the Republican system works in favor of the most conservative candidate. In six contests—including three states (Colorado, Wyoming, and North Dakota) and three territories—there are no statewide contests and the delegates are chosen by conventions. In these jurisdictions, voters can participate in precinct caucuses and, as in other states, the delegates chosen at the precinct level then move on to contests in county, district, and finally state conventions, in which the delegates are ultimately chosen. These delegates are supposedly unbound to any candidate, but it’s a system tailor-made for the base. A candidate’s campaign staff, then, has to figure out who are the potential delegates in the precincts who can get the most popular support and then turn out their followers to vote for them. This was Cruz’s forte, not Trump’s.

Trump has complained vociferously about Colorado, which ended with a state convention that awarded all of the state’s thirty-four delegates to Cruz. The process did begin with voting at the precinct level but Trump is correct insofar as it wasn’t as open as most statewide processes are and wasn’t likely to draw the new voters he’s been attracting. The Trump campaign didn’t put a paid staffer on the ground in Colorado until the last week of the convention process. When the results became known, Trump, blindsided, roared, “How is it possible that the people of the great state of Colorado never got to vote in the Republican primary?…Totally unfair!” Cruz also won the majority of delegates in North Dakota and Wyoming.

Because of the tilted Republican system the base also sets the rules of the convention and selects the party chairman. (The Democrats do the same thing.) Republican Party Chairman Priebus is sought out by the talk shows to utter his oracular sayings about the process—and to rebut Trump—but in fact he has little power by design; he is the instrument of the base.

The party “establishment” is something else–the officials and former officials such as Mitt Romney, members of Congress who want to get involved (many don’t), governors, donors, big-time lobbyists. In the past, the establishment has often picked the party’s candidate—for example George W. Bush, John McCain, and Romney—and the base went along. But this election is different: according to well-placed Republicans, the base has essentially said, Okay, we tried it your way twice and they both lost, so now we’re going to do it our way. Tom Davis, a former Republican congressman from Virginia who’s involved in this year’s election, told me, “The people who control the party reflect the grass roots and are more conservative than the congressional wing.” He added, “Some of the state rules don’t pass the smell test.”

Trump argues that even if he doesn’t have a majority of the delegates he should get the nomination since he’ll have the most delegates and have won the most votes. This evokes public sympathy, but it won’t necessarily move the Republican establishment or the base. The question is, if he hasn’t put away the nomination before the convention, how close would Trump have to come to 1,237 delegates to make it clear that it would be an extremely poor idea to try to block him from getting the nomination? Determining that number is the political, philosophical, and theological issue now preoccupying party leaders.

Advertisement

Trump’s strong victory in New York, yielding him eighty-nine of the state’s ninety-five delegates, has put him back on track to possibly sewing up the nomination before the convention. As of now, Trump has 845 delegates to Cruz’s 559. Trump is also expected to do well in the Pennsylvania primary and other states in the northeast that vote next week. The sense among political operatives is that he’ll have to win over 60 percent of the vote in the remaining contests to gain a majority of delegates.

New York was precisely the tonic Trump needed to right his campaign after his thumping loss in Wisconsin on April 5, where the more-than-usually powerful talk show hosts as well as the state’s party establishment—including Governor Scott Walker, who energetically backed Cruz—came down on him hard. Cruz beat Trump 48 percent to 35 percent. The Wisconsin primary and surrounding events were the low point in Trump’s campaign so far: he blundered into saying that women should be punished for having an abortion, showed that he understands precious little about foreign policy, and paid the consequences for going without experienced staff. Up to then, Trump had gained from his opponents’ weaknesses as well as his own shrewd reading of the anger of lower middle-class white men.

Recognizing his limitations (it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that he would), in the interval between Wisconsin and New York, Trump shook up his campaign and some experienced pros increasingly took over—including Paul Manafort, a lobbyist mainly for foreign governments who’d been active in the Ford campaign (which was a while back). Trump read from notes more than before and his speeches were shorter; his once-voluminous tweeting stream was reduced to a trickle. This suggested that he is in fact capable of learning—his adult kids, with whom he’s very close, also have a lot of influence on him. But such cosmetic changes shouldn’t be confused with a change in character.

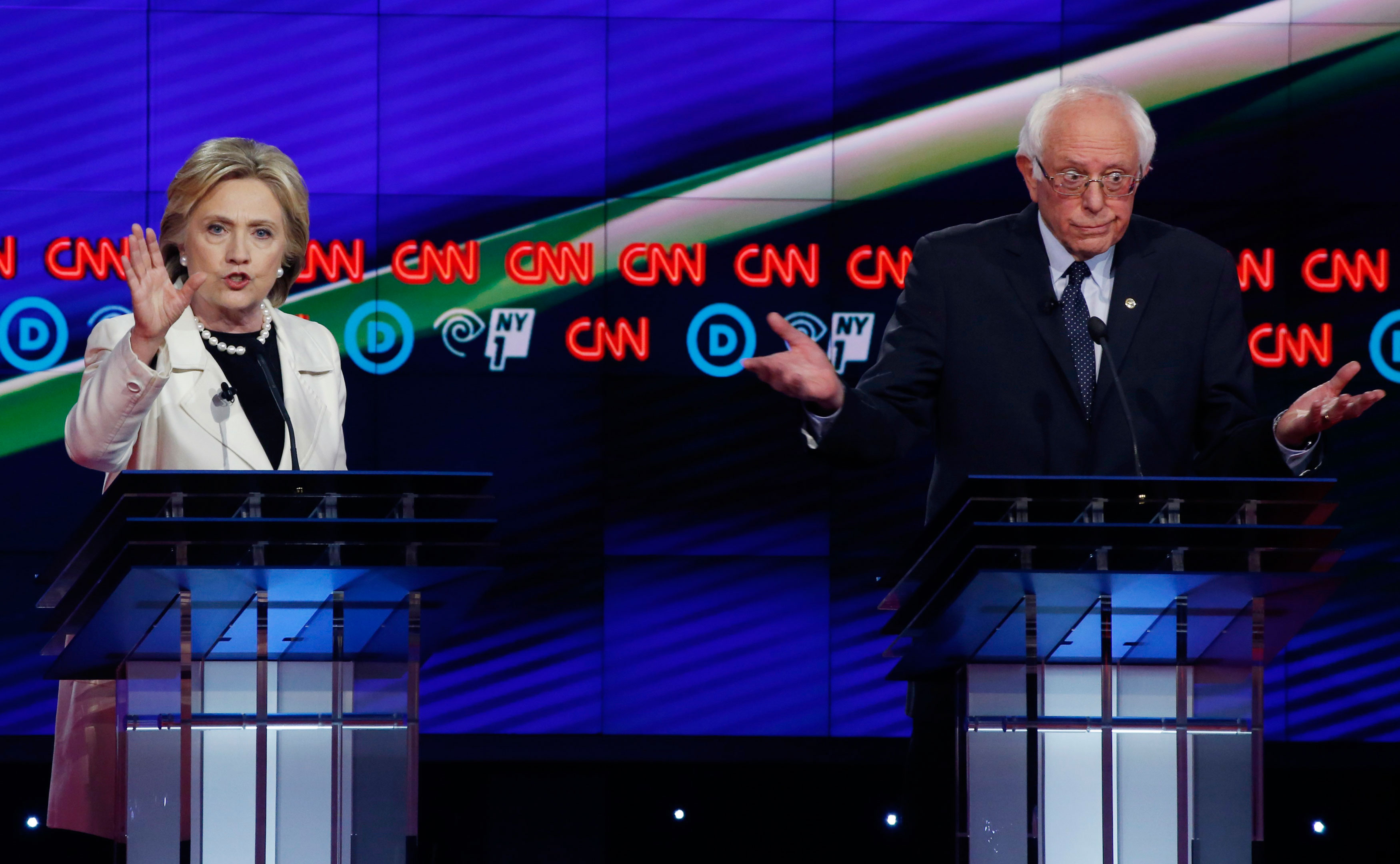

Traditionally, the New York primary has its special flavor and this year didn’t fail. New York is where the politicians do their most intense pandering and the politics become rawer. Thus the debate in Brooklyn between Clinton and Sanders was rougher and edgier than earlier ones and laid bare more differences between them. Sanders wants to go immediately to a minimum wage of fifteen dollars while Clinton prefers to reach that level in stages because the jump to fifteen would be too high in many areas of the country; Sanders continues to stress that he raises his funds in small donations while Clinton is dependent on large ones and to lambaste her for the humongous amounts she received for her Goldman Sachs speeches (though his demand that she release the transcripts is a stunt; if she does, there’ll be a lot of hooting about the obligatory compliments about her hosts but there will be no deals found). The most loaded difference that came up in the debate was over how to deal with Israel and the Palestinians. Sanders, with little to lose, took the position—in New York—that the United States should be more even-handed in its treatment of the Palestinians and Israel.

The most interesting schism that’s developed in the Democratic campaign, though—and one that sometimes put Clinton in an awkward position—is the one between her husband’s administration and the current predilections of the Democratic Party, which has moved significantly to the left since his presidency. Bill Clinton’s “third way” of governing led to a crime bill that’s now unpopular because its harsh sentencing for minor crimes has created prisons overstuffed with black youths; a welfare bill that, as its Democratic critics warned at the time, cut back the welfare program harshly, to the point that though 15 percent of Americans are in poverty only 1 percent are receiving welfare assistance; his signing of the Defense of Marriage Act, which forbade gay marriage and was later ruled unconstitutional; and his support for the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which had prohibited commercial banks from participating in the business of investment banking. This repeal is considered a major factor behind the great recession of 2008. (This break with what he’d struggled for is part of what’s led Bill Clinton to sometimes seem a bit off his game as he’s campaigned for his wife; the other part, several reporters say, is that he’s simply not as fast on his feet as he was in his heyday; his presidency ended sixteen years ago.)

The sheer shrewdness of Bernie Sanders’s campaign has startled observers who, when Sanders first announced his candidacy, shrugged him off as a protest candidate—and the evidence is that that’s what Sanders himself thought then. But though he’s done far better than just about anyone expected, he isn’t a real threat to Hillary Clinton’s nomination, and his complaint that he was put at a disadvantage by the fact that the southern states voted early skates too close to saying that blacks shouldn’t play such a large part in the Democratic nomination. Sanders’s fervent base has grown remarkably and he turned out record crowds in New York—27,000 in Washington Square last week and 28,000 in Brooklyn on Sunday. But it didn’t grow enough to catch up to Clinton, whose victory in New York brought her 139 delegates to Sanders’s 106.

There can be no doubt that the Sanders campaign has changed Democratic Party politics, among other things pulling Clinton to the left and creating a movement that will be around after the election. The Clintons are quite obviously annoyed that Sanders is sticking around when it’s evident that he cannot get the required 2,383 delegates. Sanders has reached that point that some outsider candidates, especially those with large and enthusiastic backing, do when they’ve been surprisingly successful—they begin to hallucinate that they can still win and to see their campaign as an end in itself. To be the head of a movement is intoxicating. I’ve not doubted for some time that Sanders wants to take his movement to the Democratic convention, to be held in Philadelphia shortly after the Republicans meet, and make demands about the platform and the program. And even if the oft-irascible Sanders is the soul of grace in conceding to Clinton, many of his followers will likely be another story. (A recent poll showed that forty-one percent of Sanders’s backers said they dislike Clinton.)

In fact, American voters are likely to be presented next November with two candidates who are largely disliked. A recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll had Clinton’s net negative approval rating at 56 percent and Trump’s at 65 percent—both extraordinarily high numbers. Cruz has a net negative rating of 49 percent. (The only candidates more liked than disliked are Kasich, with a net positive of 12 percent, and Sanders, with a net positive of 9 percent.)

The embrace of Cruz by the Republican “establishment” is one of the most cynical acts in in politics I’ve seen. What this gets down to is that Republican leaders, who despise Cruz, would rather lose with him than with Trump, even though Cruz represents a narrow sector of the electorate. Republican politicians and operatives figured that Trump at the top of the ticket would be ruinous for Republican members of Congress, but one wonders what happens when they wake up with Cruz in their bed. The man is simply very difficult to like. In a town hall with MSNBC in mid-April, Cruz uttered a remarkable series of sentences that were either misleading or smears; he glides smoothly from supposed fact to supposition. Drawing on the discredited propaganda film purporting to show employees of Planned Parenthood gleefully setting prices for the body parts of aborted fetuses, Cruz said, “It’s one of the sad indictments of the Obama administration. Nobody on earth thinks…the Obama Justice Department would ever investigate Planned Parenthood because they are a political ally of the administration.” Closing the trap, Cruz went on, “I think we need a Justice Department that enforces the criminal laws for…everybody.” The audience applauded enthusiastically.

But the Republican establishment is desperate. First they reckoned that all Jeb Bush had to do was announce he was running and the nomination would be his. When Bush flopped, their hopes were transferred to the youthful, melodramatic Rubio, but they either didn’t notice Rubio’s essential shallowness or didn’t think voters would catch on. And then, when Rubio went after Trump, his juvenility was exposed for all to see. Ultimately, the idea that the convention would crown House Speaker Paul Ryan the nominee crashed into the reality that it makes no sense for Ryan—or, if they really thought about it, for the party. The passion for Ryan was yet another sign of how out of touch the establishment is with the base. (Ryan is an advocate of much that the base rejects: tax cuts for the wealthy, cutting back on entitlements, and free trade.) Ryan would be a candidate on the ash heap of a bitterly divided party with most of Trump’s followers irreconcilable. That left Cruz.

The strangely persistent idea of the “white knight” riding to the rescue of the party at its convention is more myth than reality. The last time anything resembling a white knight won the nomination of either party was when the Democrats nominated Adlai Stevenson in 1952—but Stevenson had met with the approval of the party hierarchy as well as its base, and one of his champions was the retiring president, Harry Truman. A nominee who hasn’t run yet begins from a standing start; very long odds are he has no staff that’s savvy about the workings of national politics (though this can be supplied, there remain the gaps in the candidate’s own experience), no fund-raising mechanism, and little preparation on the issues. That someone could win the presidency with only the convention as his springboard is a fairly nutty idea.

Of the three remaining Republican contenders, Kasich is probably the strongest general election candidate, appealing as he does beyond the strict conservatism of the party base—but that’s made it particularly difficult for him to win the primaries and caucuses. That Kasich could be the best bet isn’t based simply on the polls that indicate that he’s the only Republican who could defeat Clinton but also on the facts that he’s the most experienced of them all and is a popular two-term governor of the electorally-crucial state of Ohio. But the establishment seems to have figured that Kasich, who thus far has won only his home state, wouldn’t go down well with the delegates—whereas Cruz would.

In all the tumult of this year, people have taken their eye off the longstanding fact that the nominating faction of the Republican Party is made up of Evangelicals and highly conservative activists, a fact that can cause problems for the Republican candidate in the general election. Both John McCain and Mitt Romney had to torque themselves between the nominators and the general electorate and it didn’t work out in either case. Before them, George W. Bush cultivated the Evangelicals to win the nomination. (In the first debate, in Iowa, his reply to the question of “Who is your favorite political philosopher or thinker?” was “Jesus.” Five of the six candidates mentioned God or Christ in the debate.) The Cruz candidacy is premised on the belief—thus far, from Goldwater to Buchanan, proven to be a myth—that there are millions of conservatives out there waiting for a candidate who’s to their taste.

The fact that some Republicans, such as Jeb Bush and Lindsey Graham, have hugged Cruz even though they heartily dislike him is a testament to how alarmed they are by Trump. But Cruz might be almost as much an election disaster, not least for his wildly conservative positions—no exceptions for abortions; a flat tax (the same unspecified tax rate for people of all income brackets) and abolishing the IRS—a sure applause-getter; a return to the gold standard; and using nuclear weapons in the Middle East that could make the sand “glow.”

And so, though each likely final candidate—if it’s Clinton and Trump or Clinton and Cruz (assuming that those are the alternatives)—will have a clump of strong supporters, most people will be casting their ballot for the one they dislike less. That’s not the healthiest start to the next presidency.