Erich Ohser became internationally famous for his comic strips in the 1930s, but the carefree world of his Father and Son gives little hint of the fate that would be suffered by its creator. After Ohser was driven to take his own life, his friend Erich Kästner wrote: “We’re going to mourn him by celebrating his drawings.” Ohser was a passionate graphic artist whose versatile talent spanned many techniques: pencil, India ink, writing ink, watercolor, and colored pencil. Alongside his journalistic cartoons and illustrations, a large body of work ranges from freehand portraits and landscapes to nudes and studies of people observed in cafés.

Born in Vogtland in 1903, he spent his childhood and youth in the newly prosperous industrial town of Plauen. Here, following his father’s wishes, he studied to be a locksmith; for the rest of his life he would recall this period as drudgery. The town paid particular attention to the cultivation and advancement of drawing—this specialty was related to the international success of “Plauen lace,” a brand name covering a range of openwork textiles. Ohser’s talent was recognized early; encouraged by his teachers, he made the move to Leipzig in 1920, and soon became a confident and successful student. He was awarded a scholarship and had his first one-man show in Plauen.

He was tall, heavy-set, and hard of hearing. Those close to him described him as humorous, awkward, curmudgeonly. The author Hans Fallada speaks of “an elephant who could walk a tightrope.”

In Leipzig Ohser met the writer Erich Kästner, and a productive friendship and collaboration developed between them. They achieved their first joint success while Ohser was still in art school at the well-respected Akademie für graphische Künste und Buchgewerbe, and Kästner was establishing himself as a newspaper wit. Even as a student Ohser gained recognition as a book illustrator and newspaper cartoonist. He contributed drawings to Kästner’s articles and books: three of Kästner’s early poetry collections appeared with illustrations and cover designs by Ohser.

Ohser also met the newspaper editor Erich Knauf, who published both Kästner’s writings and Ohser’s drawings. As an influential journalist and poet, Knauf became a formative voice in the Weimar Republic. Erich Ohser, Erich Kästner, and Erich Knauf were united in their world view and in their aesthetic convictions.

All three preferred economy of form and brevity of wit. Their eye was radically modern and unsentimental, with a severely analytical perspective on the contemporary—expressed graphically in Ohser’s case. At the Leipziger Akademie, Ohser had experimented with all the genres and techniques of drawing. He soon developed a signature style, which varied with the subject: from the emphatically artless, scratchy line of his caricatures and illustrations to his more ingratiating cartoons and comics, from the color of a few exploratory drawings to the rigorous black-and-white of his unbound sheets.

Following their initial successes, the “three Erichs” relocated to Berlin at the end of the 1920s. If Leipzig was a literary town, Berlin was a newspaper town, and it became their stage and artistic home—for Knauf and Ohser it would be the last. Knauf’s great panache and fresh ideas as the new editor of the publishing house Büchergilde Gutenberg led to its flowering; Ohser became an important cartoonist and illustrator for him. Ohser’s illustrations for the popular Russian humorist and satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko’s Die Stiefel des Zaren (The Czar’s Boots) in 1930 were received with particular enthusiasm.

Ohser had studied the great traditions of European graphics and caricature. Adapting these inspirations to his own style, he earned a reputation as a caricaturist long before he came into his own as E. O. Plauen amid the artistic and political upheavals of his time. An alert observer, he was bitingly critical of the excesses of political extremism in the Weimar Republic. Kästner’s fourth volume of poetry, Gesang zwischen den Stühlen (Song Between Two Stools), appeared in 1932 with Ohser’s design, and caused a nationwide sensation, as the previous books had done.

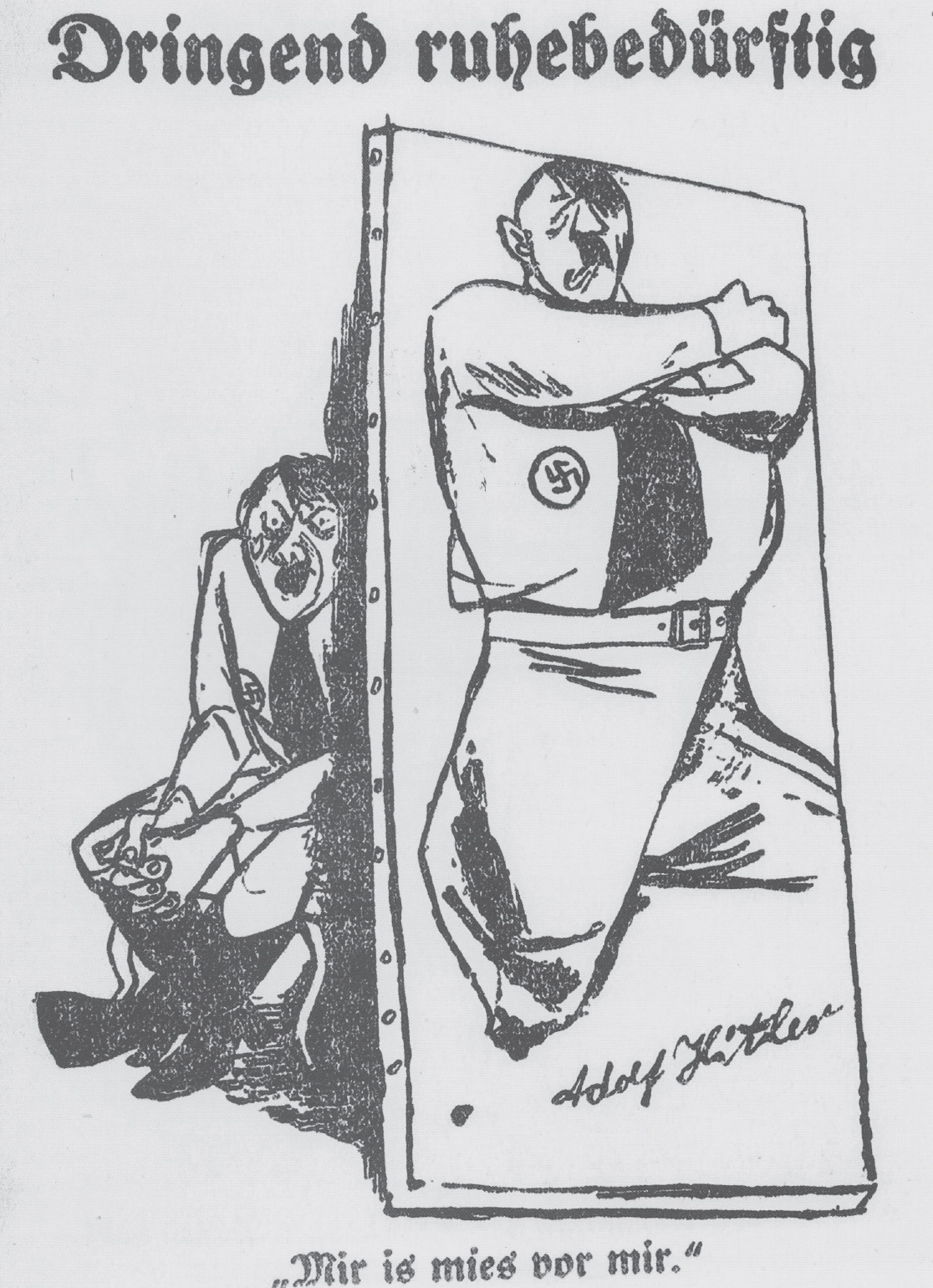

Ohser was particularly aggressive in using his skills as an artist against the emerging National Socialists. In his drawings he exposed the megalomania of Hitler and Goebbels and depicted their cohorts as gangs of dull-witted thugs, employing all the weapons of caricature: exaggeration and distortion, one-sided emphasis and intentional grotesquerie. The blunt visual language he developed for this purpose is parsimonious but effective. The originals of these caricatures, many of them published in Vorwärts, do not survive; Knauf and Ohser are said to have burned them in the spring of 1933 for fear of persecution.

Their concern was not unjustified. With the rise of the Nazis, the “three Erichs” all had to make compromises in order to stay in Germany and survive. By this time Ohser had a family: he married his one-time fellow student, Marigard Bantzer (herself an artist and children’s book illustrator), in December 1931. Their marriage was soon followed by the birth of their son, Christian.

Advertisement

After Hitler took power 1933, Ohser’s ridicule of the Nazis made it almost impossible for him to find work. Thus it was a stroke of luck when the editor of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung asked him for ideas for a comic strip. Ohser’s proposal, a strip about the day-to-day adventures of a good-natured father and his imaginative and unruly son, won him over. Ohser’s well-known and canny new editor was able to pull strings at the Propaganda Ministry allowing him to work—as long as he used a pseudonym, and worked only on nonpolitical newspaper comics. Ohser, who was not only a great inventor of gags and funny stories but also liked to play with language and dialect, remembered his Vogtland beginnings: Erich Ohser from Plauen became “E. O. Plauen.” Though this pen name was originally intended simply as a safety measure, it became so popular that the artist’s real name was practically forgotten.

The strips that Ohser delivered every week between 1934 and 1937 quickly won him an audience of millions and brought him financial success and prominence. Father and Son were not superheroes, but rather, as a contemporary critic remarked, “circus acrobats of life,” inhabiting a humane utopia. Father and Son made its creator famous during his time, but he was unable to avoid official appropriation: Father and Son was used to advertise the Nazis’ annual Winterhilfswerk charity drive. Similarly, the marketing of Ohser’s characters was sometimes a frustration to him, a situation he referenced in the strip as it wound down. Ohser’s creations were duplicated, imitated, took on an uncontrollable life of their own. Father and Son, like their creator, could not escape the evils that beset them.

He ended the strip in 1937, but kept the pseudonym and continued to work on cartoons, caricatures, and illustration. With his subtle humor and lighthearted pen he addressed the entire range of issues covered in the illustrated magazines—sports, new technology, sex roles, celebrities—striking his own idiosyncratic note.

In 1940 he was given the opportunity to work for Joseph Goebbels’s newly launched newspaper Das Reich. Ohser eventually accepted—in part because, with the outbreak of World War II, employment at Goebbels’s paper ensured he would not be drafted. So Ohser drew political caricatures of the enemies of the Reich, while still trying to differentiate between the Nazi regime and his beloved Germany. Privately steadfast in detesting National Socialism and increasingly disillusioned about the war, Ohser was walking a fraying tightrope.

Ohser felt that characterizations like “pretty” or “ugly” were a priori suspect and particularly inappropriate in an artistic context, if not plain wrong. The comprehensive reviews of his large one-man show in Berlin in 1942 demonstrate that Ohser’s drawing found recognition compatible with his principles. For example, Werner Fiedler wrote in the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung:

Plauen’s gift is to look as though he doesn’t have one. This charming con man convinces us he has forgotten everything he ever knew about composition, anatomy, and the load-bearing behavior of biological structures, because he has moved to a new phase, one of innocence.

Ohser himself spoke out in 1943 in his In Defense of the Art of Drawing:

If you draw, the world becomes more beautiful, far more beautiful. Trees that used to be just scrub suddenly reveal their form. Animals that were ugly make you see their beauty. If you then go for a walk, you’ll be amazed how different everything can look. Less and less is ugly if every day you recognize beautiful forms in ugliness and learn to love them…. Don’t be bamboozled by the virtuosity of artists, which in many cases is terribly hollow…. Vanity always trips us up—it’s very human…. A small drawing that comes from the eye and the heart is worth more than sixty square feet of inhibited, dishonest hack work.

Like the other two Erichs, Ohser considered himself a patriot and hoped the nightmare would soon end. Knauf and Kästner had found refuge working in film, also believing the era could be weathered. But the war was coming home to Germany’s civilians—all three men lost their homes to bombings. Ohser and Knauf found shelter in a building on the edge of devastated Berlin. There, imagining they were safe, they aired their resentment and desperation in jokes about Hitler, Goebbels, and the hopeless war—and were denounced by their neighbors. They were arrested in the spring of 1944, and quickly sentenced to death. Ohser eluded his executioners and committed suicide the night before the hearing. He was just forty-one years old. His friend Erich Knauf was executed a month later. Kästner was the only one of the “three Erichs” to survive the Third Reich.

Advertisement

With pencil in hand, Erich Ohser explored his world, again and again finding the comic and grotesque aspects of any situation. Even after his tragic end, his art endures, as does the encouragement he gave us to rediscover his world and ours.

Adapted from the afterword to Father and Son, by E.O. Plauen, translated by Joel Rotenberg, recently published by New York Review Comics.