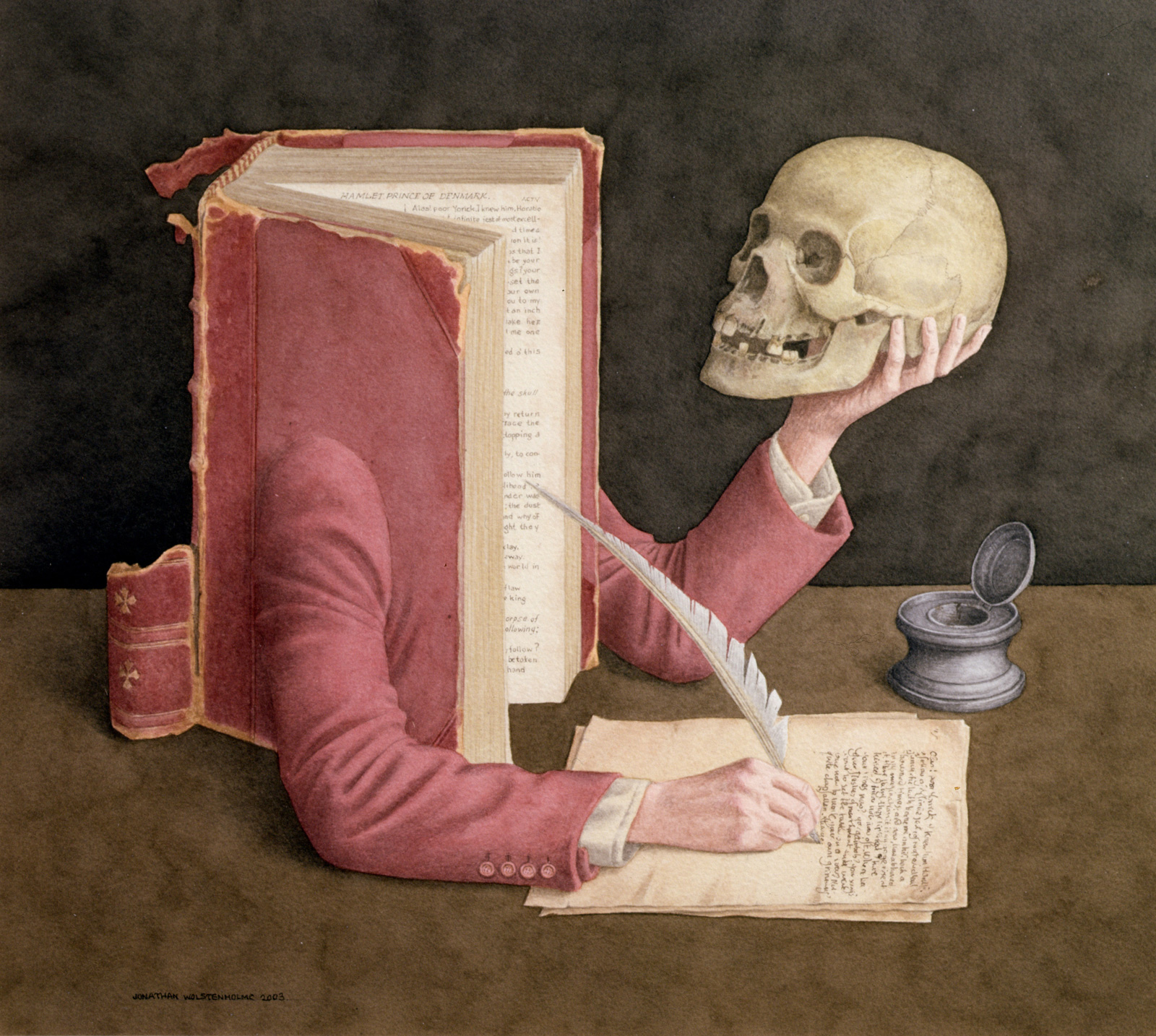

Why do we have so many novels and films featuring writers and artists? Films abound—Amadeus, Picasso, Turner, Oscar Wilde, Neruda, Leopardi. In fiction we have, among others, Michael Cunningham’s Virginia Woolf in The Hours, Colm Tóibín’s Henry James in The Master. And now the English novelist Jo Baker has dramatized the war years of Samuel Beckett.

What is the attraction? With intriguing variations, the underlying plot is mostly the same and, in the end, not so unlike Joyce’s autobiographical novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. We savor the artist’s growing awareness of his or her specialness, which becomes one with a particular, always unconventional vision of the world, a peculiar style of thought, an almost mythical superiority to run of the mill experience. And we marvel at society’s obtuseness, its determination to obstruct this special sensitivity, which the reader at once admires and yearns to share, perhaps conceding a little of the same to the author of the new work—Tóibín, perhaps, or Cunningham—who thus borrows some glory from his or her more celebrated subject.

If there is a risk in a project like this, something the straightforward biographer need not worry about, it is the danger of being compared, as an artist, to the artist hero. A poem about Leopardi would very likely invite the reader to reflect that Leopardi was the finer poet. Likewise a novel that took, say, Hemingway as its hero. Always assuming, that is, that contemporary readers are sufficiently familiar with Leopardi’s poetry, or Hemingway’s novels. If they are not, there is the second problem that, unaware of the real achievement of the artist/hero in question, they may simply not appreciate why the subject is worth so much attention. They cannot pick up the allusions that link the great writer with his or her work.

In The Master, Tóibín has James notice a little girl performing an innocence that she doesn’t perhaps truly possess. The reader is presumably supposed to realize, Ah, so that’s where What Maisie Knew came from! If you’ve never read What Maisie Knew it’s hard to see what’s so interesting. If you’ve not only read the novel, but reread it and admired it deeply, this kind of connection might seem simplistic. It’s hard to see how a writer can get around this. Certainly this kind of novel is stronger when it dramatizes a pattern of behavior in line with what we find in the novels, rather than merely image and incident.

Jo Baker’s previous novel, Longbourn, was also a form of benign literary parasitism. Just as Tom Stoppard once focused on two minor figures in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to give us Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Baker dramatized the life of the servants who minister to the main characters of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. But while Stoppard offered a sparkling absurdist play, Jo Baker’s work is solid realism, insisting on the physical effort and sheer drudgery of those who served the privileged. Alongside the fun of recognizing events in Austen’s novel, as seen and interpreted by the servants, there was also the satisfaction of agreeing that inequality of opportunity is an ugly thing and feeling mildly superior to the Bennet family and their time.

To move from this charming entertainment to dramatizing the life of the twentieth-century artist who, more than any other, insisted on his apartness, his reticence, and privacy, a man who felt the traditional novel, and indeed language in general, was utterly inadequate to express experience, or, worse than inadequate, mendacious, suggests ambition of a different order. Both Henry James and Virginia Woolf had developed elaborate styles to mimic the unfolding of consciousness, suggesting how their own minds moved. This allowed Tóibín and Cunningham—great talents in their own right—to imitate those styles and achieve a certain authenticity for their imaginings; they seemed close in spirit to their literary heroes, as if their books were a natural continuation of the earlier authors’ endeavours.

But Beckett did no such thing. He did not believe that words could express interiority, or really very much at all, and his work never presents conventional reality in a traditional manner. “It is indeed becoming more and more difficult, even senseless, for me,” he observed, “to write an official English. And more and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it.”

To attempt, then, to present this man as the hero of a traditional realist novel with an omniscient narrator who moves effortlessly in and out of the most intimate thoughts of both Beckett and his partner, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, when they’re enjoying or failing to enjoy love-making, fleeing the Germans, or simply drinking with friends, inevitably suggests an abyss between the sensibilities of Baker and her hero. She ably describes a lanky, diffident, disconnected man who looks like the Beckett of the photographs and behaves as Beckett is described as behaving in the biographies, but the moment we become privy to his thoughts, it is very hard to imagine we are reading about Beckett at all. “How easy,” wrote Emil Cioran, “to imagine [Beckett], some centuries back, in a naked cell, undisturbed by the least decoration, not even a crucifix.” How much more difficult to think of him worrying that Suzanne will be upset if he stays out for another whisky or two.

Advertisement

Baker’s title, A Country Road, A Tree recalls the stripped-down stage directions that open Waiting for Godot. The idea of her novel is that it was Beckett’s wartime experiences that took him from being a rather pathetic Joycean acolyte, seeking and failing to reproduce the richness of his mentor’s work, to becoming an independent artist with a clear sense of a quite different project, to present experience in its most basic and irreducible manifestation, something very like the tired, broken, hungry, unwashed body of the many war refugees with whom he would share his life in these years. In reality, in the letter quoted above, written in 1937, Beckett had already remarked that he was headed in a very different direction from Joyce.

Baker begins her story with Beckett deciding to return to Paris and Suzanne after a holiday in Ireland, despite England’s declaration of war on Germany, despite his widowed mother’s desperation, despite having no apparent part to play in the forthcoming conflict. It then tracks the couple’s confused movements first to the South of France, following Joyce and other friends—Joyce was to die shortly after reaching Switzerland—then back to Paris during the occupation. At this point, Beckett gets drawn into the French Resistance, collecting and correlating information passed to him by different agents. It was a major step for one who had always had difficulty involving himself in any kind of collective enterprise. Baker gives us his supposed emotions and thoughts as he types out a message indicating a movement of warships that will very likely cause the British to bomb Brest:

His fingertips peck out the letters, and the letters strike on to the paper, and the letters cluster into words, and the words seethe on the page, and he can’t bear this and yet it must be borne. He swallows down spittle, closes his eyes. All he can see is fire and blood and broken stone.

Eventually betrayed, he and Suzanne take refuge in safe houses, and are then helped to escape, not without various heart-in-mouth vicissitudes, south to Roussillon, in the so-called free zone above Marseilles, where they live in a small community of likeminded exiles and in constant fear of further betrayal. Anxious not to be entirely passive, Beckett again becomes involved in the Resistance, storing explosives and helping to impede the German retreat. Returning to Ireland and his mother at the end of the war, he sees no hope of remaining, but at last experiences the revelation of the path he must pursue. The wild Joycean “hubbub,” as Baker has Beckett imagine it, must be abandoned for the essential profile of a stark figure against the night. He goes back to France to work in a field hospital as part of the process of reconstruction, then finally heads for Paris and Suzanne where, at last, he can sit down in peace and unburden himself of all he must write.

There is much opportunity for action and melodrama here. Hunger, terror, cold, pursuit, gunshots, rationing. Baker tells it in an emphatic, evocative style. Suzanne’s face is “open as a wound.” Beckett feels “a gut-punch of guilt.” British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s voice “spools” from the radio and “tangles” across the floor. Moonlight “kicks off Perspex.” A car “burns through scattered dwellings.” A train “is peeling past.” And so on.

Meanwhile, the images crucial for Beckett’s future work are patiently gathered. A painting by Rouault where “trees stand like gibbets by the roadside” has Beckett raptly gazing; it’s the setting for Godot. Hungry, Beckett sucks a stone, and the knowing reader looks forward to the hilarious sucking-stone routine in the later novel Molloy. During a conversation “soft words accumulate, like sand trickling through an hourglass. They are up to their knees in it and yet still they can’t stop.” One cannot, of course, be up to one’s knees in an hourglass, but the mixed metaphor allows us to look forward to Happy Days, where the lead actress is slowly buried in sand. Feeling “shambolic. A broken-down old tramp. A mummy,” Beckett himself metamorphoses into one of the battered figures in his later fiction.

Advertisement

It’s all admirably earnest, but never convincing. Nor does Baker know what to do with the relationship between Beckett and Suzanne. Alternating between admiring facilitator and exasperated mother figure, adoring or nagging, Suzanne never emerges as the intellectual she was. She is shown despairing over the doodles Beckett made while trying to translate his early novel Murphy into French, but we hear nothing of her reaction to the utterly bizarre and quite wonderful novel, Watt, that Beckett wrote while waiting the war out in Roussillon. It is as if Baker herself had no idea how to put this strange achievement in relation to her hero’s wartime life.

When Beckett and Suzanne are imagined waiting by a tree as night falls for a contact who is to take them across the border into the free zone, and begin to use, when the contact doesn’t show up, almost exactly the words from Godot, the whole strategy is revealed as embarrassingly mechanical. Very likely, the war years did offer Beckett images and experiences that, stripped of context, he would make universally powerful, but speculatively reconstructing the context to then color it with the melodrama Beckett assiduously pared away hardly seems a helpful exercise.

In an afterword, as if to justify her efforts, the author offers an uplifting moral gloss on her story. During the war, in “impossibly difficult situations, [Beckett] consistently turned towards what was most decent and compassionate and courageous… he grew, as a writer and as a man. Afterwards he would go on to write the work that would make him internationally famous, and for which he would be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.” What a happy formula: goodness, personal growth through hardship, artistic fame. It is the reductio ad absurdum of this strange form of fiction that would have us consume our literary heroes in a conveniently palatable sauce.

“Work that still resonates powerfully with us today,” Baker goes on to say, using the sort of pat phrase that had Beckett comparing conventional prose with a Victorian bathing suit. Not powerfully enough, one might object, if this is the novel it has led to. Here, by way of decontamination, is Beckett from Watt. Our eponymous hero has been struggling with the feeling that the word “pot” no longer seems quite right to denote, well, the thing he used to call a pot. The mismatch makes him anxious.

Then, when he turned for reassurance to himself… he made the distressing discovery that of himself too he could no longer affirm anything that did not seem as false as if he had affirmed it of a stone. Not that Watt was in the habit of affirming things of himself, for he was not, but he found it a help, from time to time, to be able to say, with some appearance of reason, Watt is a man, all the same, Watt is a man, or, Watt is in the street, with thousands of fellow-creatures within call.… And Watt’s need of semantic succour was at times so great that he would set to trying names on things, and on himself, almost as a woman hats. Thus of the pseudo-pot he would say, after reflection, It is a shield, or, growing bolder, It is a raven, and so on. But the pot proved as little a shield, or a raven, or any other of the things that Watt called it, as a pot. As for himself, though he could no longer call it a man, as he had used to do, with the intuition that he was perhaps not talking nonsense, yet he could not imagine what else to call it, if not a man. But Watt’s imagination had never been a lively one. So he continued to think of himself as a man, as his mother had taught him, when she said, There’s a good little man, or, There’s a bonny little man, or, There’s a clever little man. But for all the relief that this afforded him, he might just as well have thought of himself as a box, or an urn.

Extraordinary how Beckett, taking an axe to the relation between words and things, conveys and entertains so much more than the novelist who confidently puts words to his inner thoughts. We should read our great authors, not mythologize them.