About five miles north of the Israeli city of Beersheba, on the edge of the Negev desert, there’s a small village named Al-Araqib that has been demolished more than a hundred times in the last eighteen years. These demolitions have ranged from the total razing by over a thousand armed policemen with trucks and bulldozers to a simple flattening of a tent by a tractor.

In its heyday, the village had about 400 inhabitants, though now only a dozen or so remain, living within the limits of the village cemetery, next to the many graves. The cemetery affords the main claim of the Bedouin villagers to the land—if they can prove that they have cultivated it since before 1948, that the village has existed for longer than that, then the Israeli government will let them stay.

The plight of this village—shared by forty-six others that have been collectively dubbed “the battle of the Negev” by the Israeli media and establishment—is one of the many cases of state violence examined in “Counter Investigations,” an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London detailing the work of an investigative agency called Forensic Architecture. The group, founded by the Israeli architect Eyal Weizman in 2010 and based at Goldsmiths College in South London, seeks to use forensic methods of evidence-gathering and presentation against the nation states that developed them. Weizman believes that architects, who are skilled at computer modeling, presenting complex technical information to lay audiences, and coordinating projects made up of many different experts and specialists, are uniquely suited to this kind of investigation. But there’s another, simpler explanation for their involvement: “Most people dying in contemporary conflicts die in buildings.”

From missiles designed to pierce a hole in a roof before exploding inside a particular room, to army units blasting through the walls of houses, to the repeated demolitions of villages like Al-Araqib, conflict has increasingly acquired an architectural dimension. This development has prompted a wave of work by writers, artists, and academics such as Sharon Rotbard, Derek Gregory, Trevor Paglen, and Hito Steyerl focusing on the intersection between design, warfare, and the city. Steyerl, for example, writes in her recent book Duty Free Art that killing is a “matter of design” expressed through planning and policy; like Weizman she asks us not just to examine the moment a gun is fired, but also the ever-widening scope of circumstances and legal mechanisms that make such violence possible, even inevitable.

Weizman studied at the Architectural Association in London, and published his first book in 2000, Yellow Rhythms: A Roundabout for London, an eccentric proposal for a vast roundabout straddling the Thames in southwest London, just north of Vauxhall. This was less a sincere attempt to solve traffic congestion and more an inventive thought experiment designed to reveal the absurdities and inequities of the London real estate market. Weizman imagined a state-owned, speculative development in the center of the roundabout—a set of empty skyscrapers accumulating value that would be skimmed off and used to fund progressive policies elsewhere. With this project Weizman embraced an attitude that had flourished at the AA and a number of the other innovative architecture schools since the Sixties: that architecture is a way of thinking about the world, of synthesizing and presenting knowledge, rather than just a way of designing and constructing buildings.

Within a few years, Weizman was able to put this approach to the test. Weizman, along with his colleague Rafi Segal, was selected to represent Israel at the World Congress of Architecture of Berlin in 2002. As part of the exhibit, the pair put together a catalogue of fourteen essays detailing the different ways in which the business and practice of architecture was part of Israeli strategy in the West Bank. The result, entitled A Civilian Occupation, was banned by the Israeli Association of United Architects, which ordered the pulping of the 5,000 printed copies (Segal and Weizman managed to save around 850, and the book was later re-released by Verso Books and the Israeli publisher Babel). Weizman built upon these ideas in his 2007 book Hollow Land, a sweeping investigation of Israeli policy from an architectural point of view that combines polemical force with minute, often surreal detail gleaned from interviews with Israeli military officers: “Derrida may be a little too opaque for our crowd,” says one, unexpectedly. “We share more with architects; we combine theory and practice. We can read, but we know as well how to build and destroy, and sometimes kill.”

Advertisement

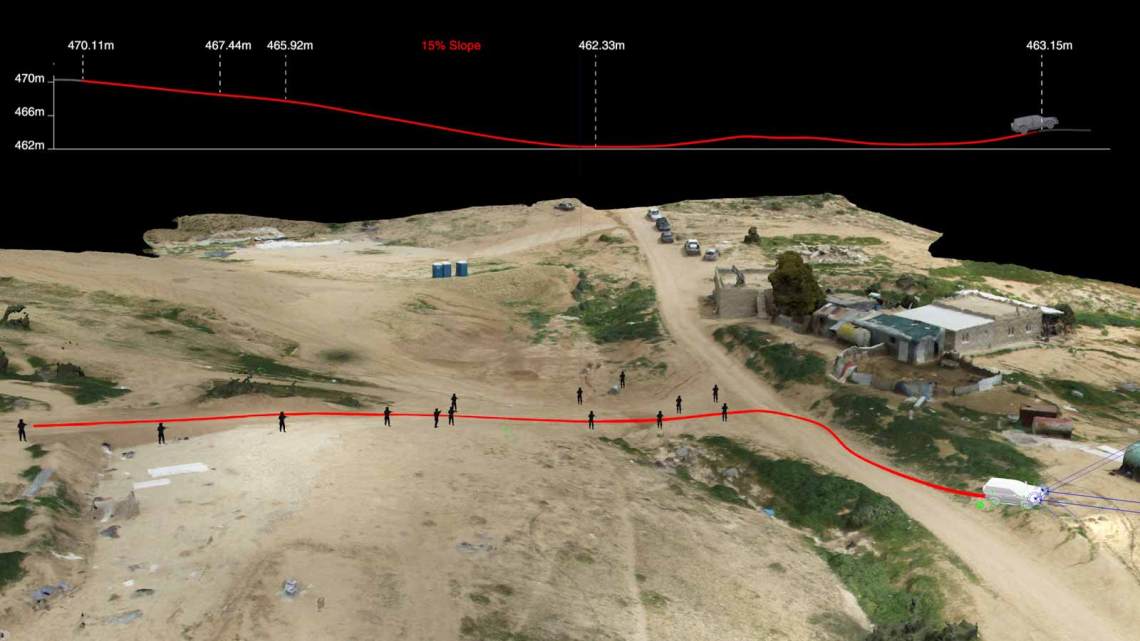

Through this work Eyal Weizman, and later Forensic Architecture, has been involved in numerous court cases in Israel—most successfully as part of an action in the Israeli High Court designed to halt the construction of a section of separation wall in the village of Battir on environmental grounds. The agency provided models and animations demonstrating the environmental damage that would be caused by various army engineer proposals for a more “architecturally sustainable” and less “invasive” form of wall—leading to the idea of a wall in that area being abandoned altogether. Wider work by the agency has been used in trials from Guatemala to the International Criminal Court at the Hague, with similar aims—to use visualization and modeling to bring a complicated set of relationships vividly to life in the courtroom. This can have varying results, and their work is ignored or dismissed as often as it produces dramatic turnarounds. Battir might have been saved, but the future of the village of Al-Araqib, for example, is still precarious despite exhaustive historical research and a number of court sessions.

Although showcasing some of the agency’s work in Israel, where Weizman and his colleagues continue to collaborate with civil society groups and human rights organizations such as ActiveStills and B’Tselem, the main purpose of the London exhibition is to show how Forensic Architecture adapts its practice to provide a commentary on its immediate location. The show is squarely aimed at a British audience during a period of mounting hostility toward refugees and migrants. Immediately after the referendum to leave the European Union, for example, there was a documented spike in hate crimes in Britain, and they have yet to fall below pre-referendum levels. The exhibition has coincided with a long overdue public discussion about a policy once proudly described by Prime Minister Theresa May as the “hostile environment,” in which both non-citizens and British citizens of color have faced the same labyrinthine bureaucracy and a pervasive attitude of skepticism when trying to prove their right to be in the country. Preliminary figures suggest that thousands of citizens have suffered at the hands of this racist system in recent years, leading to destitution, lack of healthcare provision, and sometimes even deportation.

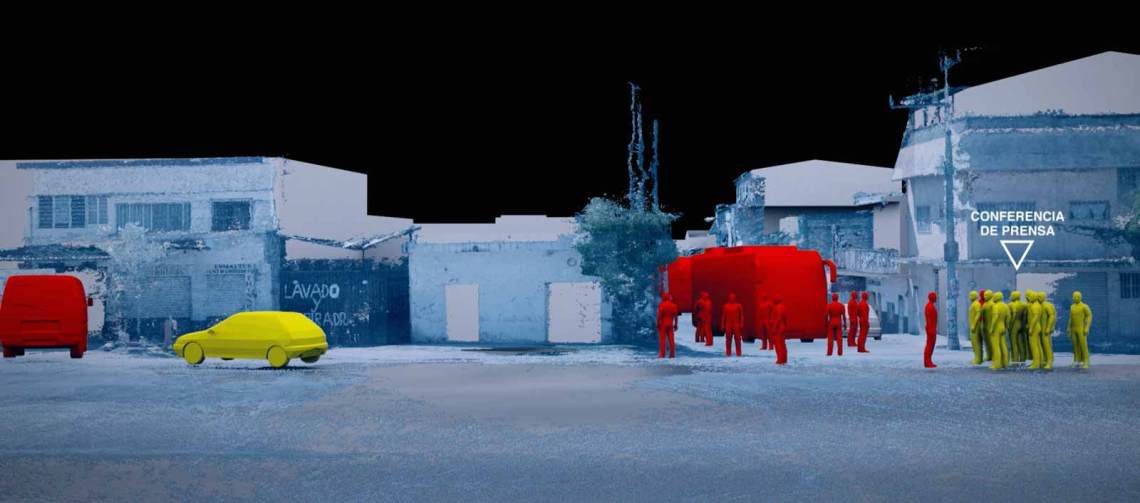

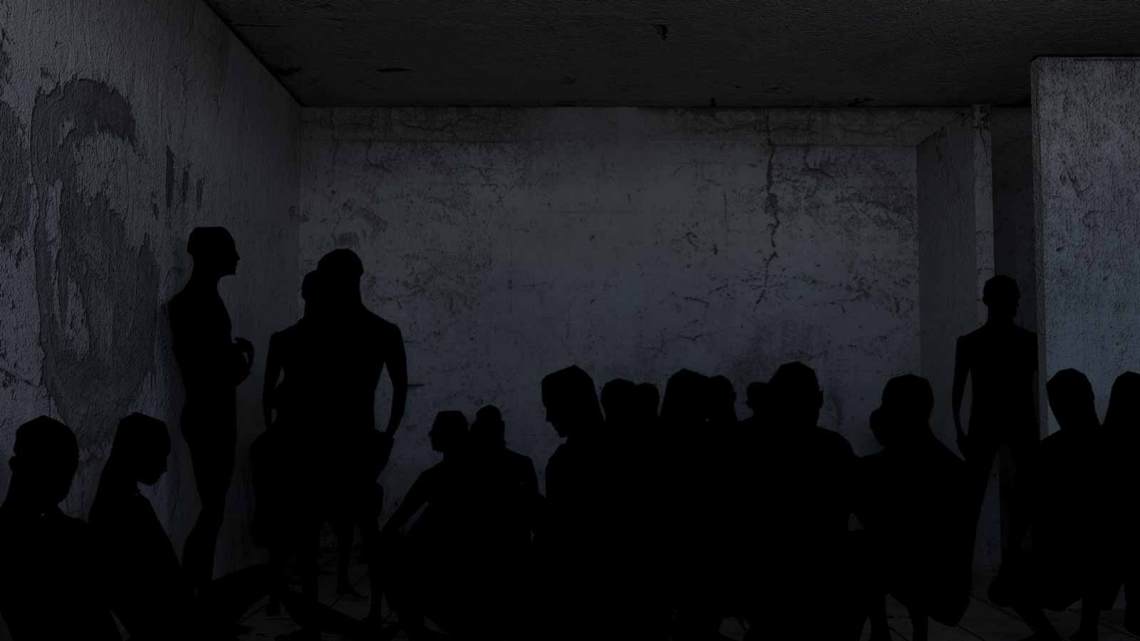

The show’s curators have subtly assembled parts of the exhibition to address this political background, in which issues surrounding race and immigration regularly dominate British media. The first project in the show uses videos, a vast timeline, and outlines traced on the gallery floor to reconstruct the murder of a Turkish man by a neo-Nazi in Germany, while another uses survivors’ testimonies to construct a harrowing model of a secret torture prison in Syria called Saydnaya. The latter project, perhaps their most famous to date, was carried out by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, a member of the group specializing in sound analysis. Through an immersive video shown at the exhibition, we see Hamdan working with survivors to reconstruct claustrophobic visual models of the interior of the prison, according to the sounds they heard while held there, or transported to and from torture cells, in near total darkness. Hamdan’s approach preserves gaps and errors in the memories of the survivors, and makes visual the trauma they experienced—corridors stretch to impossible lengths, while sinister locked doors multiply and spread around the viewer. These eerie plans, resembling a nightmarish memory palace, testify not just to the physical existence of the hidden prison, but also to the psychological consequences of what happened there, persistent in the minds of the survivors.

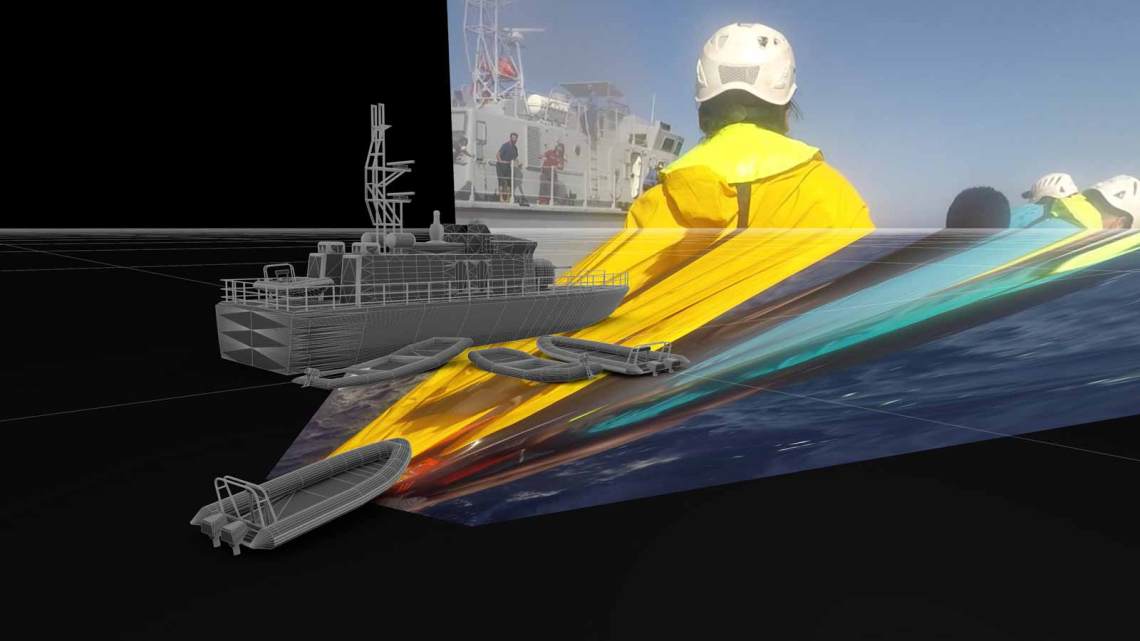

Beyond the film about Saydnaya, as the exhibition moves deeper into a cavernous darkened room, three video projections break down into traumatic detail the way that a lack of coordinated sea rescue services extracts a terrible death toll among migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean: while different European authorities, NGO ships, and Libyan Coast guard vessels jostle chaotically, refugees drown, sometimes only feet away from the boats that are supposed to rescue them. (One such death is shown on film, captured by a camera fixed to the side of an NGO boat, and cannot be forgotten once seen.) According to Forensic Architecture’s Research Coordinator Christina Varvia, the purpose of these displays—from Germany, to Syria, to the Mediterranean Sea—is to viscerally impress upon a British audience the brutal reality of the refugee experience—whether it’s the violence they’re fleeing from, the dangerous, often deadly journey they face if they try to reach Europe (most don’t), or the racism they often encounter once they get there.

Advertisement

It is a testament to the group’s media fluency and inventive presentations that the sheer quantity of depressing, disturbing information on display in this exhibition rarely feels wearing or boring. For all its focus on precisely reconstructed factuality, many acutely emotional moments linger in the mind long after seeing the works. Whether or not this is “art” is a debate that Forensic Architecture long since left behind—the group is adept at presenting its findings in galleries and courts alike. (The art establishment is clearly not troubled by the question either: Forensic Architecture has been nominated for the prestigious Turner Prize.)

Why, when nation states have always committed crimes and lied about them, has an organization such as Forensic Architecture appeared only in the last decade? In Duty Free Art Hito Steyerl argues with apocalyptic brio that the world is entering a period of “post-democracy,” in which “states and other actors impose their agendas through emergency powers,” while democratic mandates weaken and “oligarchies of all kinds are on the rise.” Perhaps the group owes its existence to this new mood, in which authorities can no longer be trusted to handle the evidence, and impartiality seems increasingly impossible or, in Weizman’s opinion, even undesirable. “Having an axe to grind,” he writes, “should sharpen the quality of one’s research rather than blunt one’s claims.”

“Counter Investigations: Forensic Architecture” was at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts through May 13. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability, by Eyal Weizman, is published by Zone Books. Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War, by Hito Steyerl, is published by Verso.