Culture was big in the USSR. Many avenues existed for the model Soviet citizen to develop herself culturally. In the Palaces of Culture, for instance, one could sign up for amateur dance and singing “circles,” attend lectures on the harm of alcoholism, even participate in amateur productions of Hamlet. Younger members of the society could go to lavish Pioneer Palaces that offered instruction in everything from music to step-dancing, ballet, journalism, and theater (I did all five in the 1980s, though not concurrently). We also participated in kultpokhody, or organized expeditions to various cultural establishments. Our southern town, Krasnodar, the capital of an important agricultural region, had a philharmonic orchestra, three theaters (for operetta, drama, and puppet), and a permanent circus.

A weekly newspaper, Soviet Culture, published detailed explanations of the culture-related decisions of the Communist Party, and sang the successes of Russia’s ballet dancers and the era’ wunderkind pianist Zhenya Kissin. My mother subscribed to Soviet Culture for professional reasons: she had a job at the Institute of Culture, an unadorned five-story block on the edge of the First-of-May Park in Krasnodar.

The Institute was no palace. Its purpose was simple: to produce culture warriors—librarians, choir conductors, orchestra musicians, dance collective directors, museum curators, mass leisure organizers. An important aspect of the work was organizing the best November 7 displays to commemorate the October Revolution, performing inspiring tableaux and pirouettes in front of the regional Party Committee building. Most students of talent and ambition went straight to one of Moscow’s renowned conservatories, ballet companies, or theater schools, bypassing our local Institute of Culture. Still, the Institute had its fair share of applicants; they offered a higher education diploma, a deferment from military service, and a stipend.

My mother had passed up a chance to do a master’s degree at the Moscow Conservatory under the patronage of Dmitry Shostakovich, a family friend, and instead married my father in 1970 thinking that she was choosing family bliss and stability over the uncertainties of starting a professional life in the arts from scratch in the capital. And things began well. In Krasnodar, in addition to her job at the Institute, she enjoyed minor celebrity status as a local TV host on a classical music show—to the extent that shows like What If Grieg Kept a Diary could make one a celebrity in the land of wheat fields, tractors, fertilizer depots, and dairy farms. But it paid well and, according to witnesses, my father was a handsome man.

The TV job came apart first. Just before my mother’s wedding, Brezhnev paid a visit to Novorossiysk, a nearby port where my grandfather used to be the mayor. Brezhnev was a soccer fan, and to ensure that the General Secretary could watch Spartak vs. Dynamo games while he was touring the south, the city authorities hooked up a military transceiver to rebroadcast Moscow channels otherwise unavailable in our region. Touched, Brezhnev helped out by funding a permanent TV tower. Beaming Channel 1 to the masses, however, meant that local programming had to be cut to eight hours a week for everything, including such priorities as Agricultural Hour and weather reports. My mother’s biweekly music show became monthly, then bimonthly. By the time I was born, in 1972, it was no longer on the regular schedule.

The marriage lasted five years more, and when it collapsed, it was without Brezhnev’s intervention. The official reason for the divorce was “character incompatibility.” Unofficially, my mother must have rebelled against the pedagogical tool my father favored after extracurricular drinking sessions at his Institute, that of Physical Culture: a jump rope.

Thus, by 1977—the year a new Soviet constitution proclaimed the USSR’s official transition to the era of “advanced socialism”—what my mother had left was me and her job teaching piano to non-piano majors in the Cultural Enlightenment Faculty of the Krasnodar Institute of Culture. Mother always said she was fine with this. But sometimes, when I glanced at the portrait of Shostakovich hanging above the black Zeller piano that Grandfather had brought home from Berlin in 1945, I wondered whether, if things had been different, there might have been a way to combine the Moscow Conservatory and me.

Like most Soviet labor establishments, the Institute of Culture paid poorly. Staff salaries were on a fixed scale and rose only on length of service: 105 rubles per month at entry level, 125 at the five-year mark, and 140 at the ten-year mark for the senior teacher level, at which point increases ended. The next change happened at retirement: every Soviet citizen was entitled to a pension equaling half her pay. Being in her early thirties at the time of her divorce, my mother was far from retirement, and the 140 rubles she earned was not enough to support us even if we shopped only at state grocery stores, which stocked next to nothing to begin with. And my growing body demanded proper nourishment.

Advertisement

A wolf is fed by its feet, a Russian proverb goes, and nowhere was it more true than in the sphere of provincial kultur drudgery. While industrial workers and farmers could get productivity-related bonuses and free food around holidays, no such incentives existed at the Institute of Culture. Instead, the competition for side jobs like tutoring, even at the meager rate of three rubles per hour, was fierce: teachers outnumbered students, pianos and violins kept getting more expensive, and the rise of record players and cassette recorders was slowly eliminating the demand for live music at birthdays and holiday gatherings.

Mother had just two regular piano students. One was the daughter of a restaurant chef who lived in an identical five-story apartment building next to ours. The chef would sometimes feed me in the kitchen while her daughter stumbled through a Kabalevsky piece, or give Mother, at the end of a lesson, a kilogram of meat she’d managed to “withhold” from her restaurant kitchen by putting less than required into stews and soups. “What’s the point of being educated?” she liked to ask my mom. “You study all your life, then come to us not to starve.”

Mother’s other student was Lyuda, a petite brunette with round, bulging eyes, whose father had built for us, as an act of gratitude for imparting culture to his daughter, a floor-to-ceiling storage closet in the corridor of our apartment, a feat of ingenuity given the corridor’s cramped dimensions. The closet held our winter coats and fur hats, my rollerskates and jump rope, and our “Uranium” vacuum cleaner, which, when running, rivaled the Trumpet of Jericho. The shelved area contained jars of homemade preserves and the electricity meter, which some less socially conscious citizens knew how to stop with a magnet.

Lyuda also babysat me on weekend nights when my mother played accompaniment at the Club for Those Over Thirty, to which unmarried women flocked in search of husbands at a somber four-to-one-man ratio. Thanks to Lyuda’s generosity, I discovered while still of elementary-school age that I liked neither beer nor cigarettes. Sharing those sentiments with Mother ended the babysitting arrangement, but not the music lessons. Those continued all the way through Lyuda’s wild adolescence, which ended, rather miraculously, in a happy marriage and motherhood. Thirty years later, when Mother was leaving town for good, Lyuda bought our old black piano, in gratitude “for the memories.” She then painted it white, with epoxy floor paint, to match the furniture in her living room.

Mother’s other cultural-financial pursuits included piano gigs in village clubs, for which the management of collective farms would sometimes pay in rubles, but more often in bags of potatoes, flour, or kasha grain. One time, three days before the Mayday holiday, she and a bunch of Institute musicians performed at one such club and each received a young goose. Normally, this would have been considered unbelievable luck—meat was almost nonexistent in the early 1980s, even in a meat-producing region like ours. But the goose was very much alive, and had to be carried, without a cage, back to our apartment and somehow accommodated until a suitable neck-breaker could be found. I was spared the procedure and next saw the goose plucked and in the roasting pan, small and pitiful against the thick cast-iron sides. It yielded three dinners for two.

Amid all this cultural production, Mother managed to get into a feud with the Piano Department chairman, jeopardizing her position at the Institute, to which she had to be “re-elected” every five years. The chairman was twenty years older than she was, and had a shock of graying wavy hair that flew up dramatically when he played Beethoven’s “Appassionata” at the Institute’s holiday concerts. He had grown up in a labor camp, where his parents had been exiled as “Polish traitors” just after the war. When Stalin died, the chairman had been admitted to a conservatory and had gone on to a successful career as a concert pianist before landing at the Krasnodar Institute of Culture and becoming my mother’s boss.

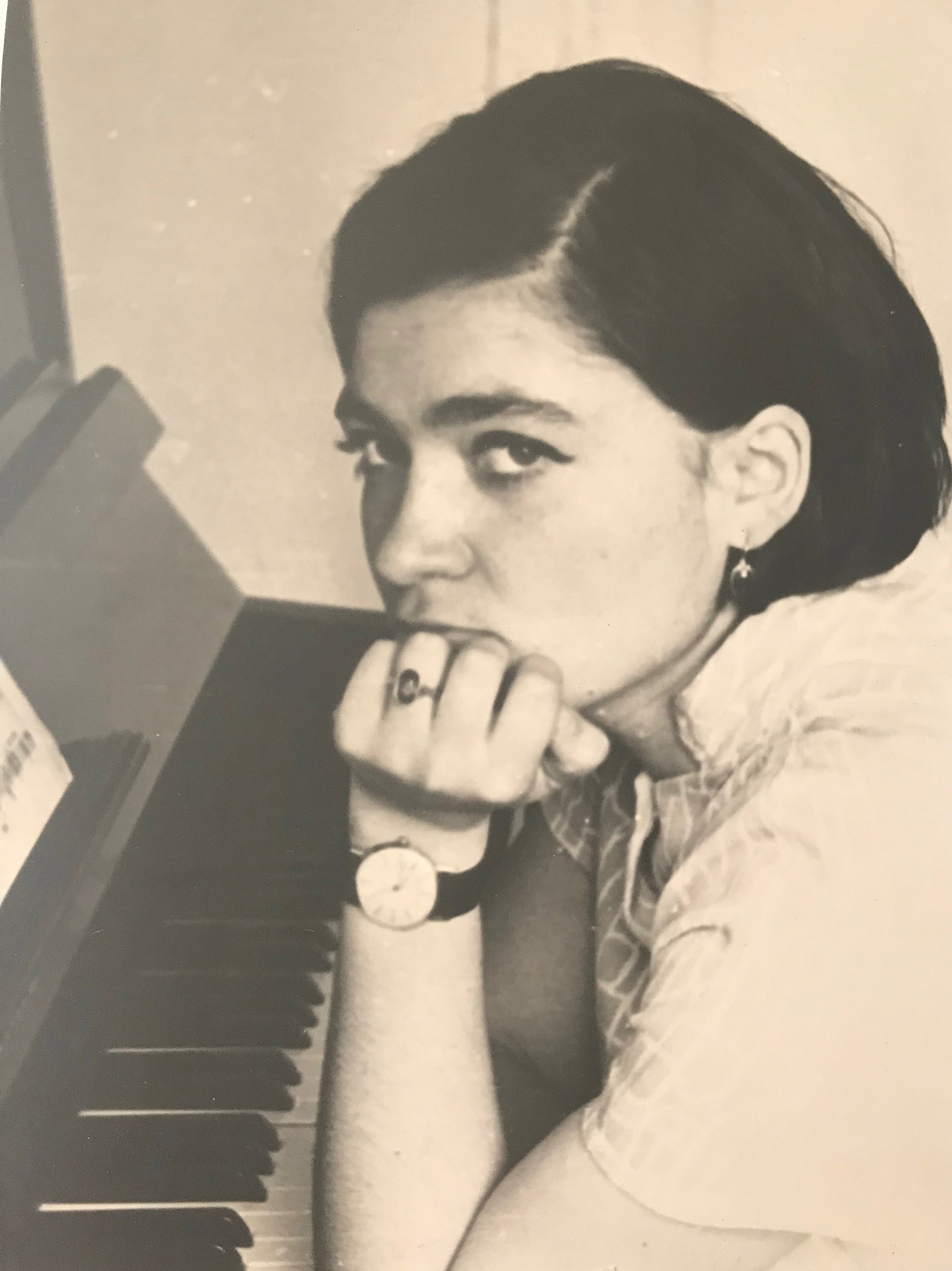

For his first few years at the Institute, he adored her, entrusting her with the department seal and the right to supervise exams in his absence. He complimented her on the way she dressed, or styled her black hair, in a short bob, or on the way she applied makeup to her large eyes she’d inherited from her Greek mother. He also took a liking to me, since I was an enthusiastic concert-clapper for everything from his “Appassionata” to the “Young October” anthem performed by the Institute choir and folk ensembles. His wife worked as a cashier in a grocery store, and he would often send me, via Mother, illicit treats like bacon or candy.

Advertisement

Yet I was the reason for their discord. One June, just before final exams, the Regional Party Committee declared a “Month of Fighting Ambrosia,” a local weed with allergenic qualities. The Institute management responded by summoning all students and teachers to a “spontaneous” subbotnik, or volunteer group work, that would attack the weeds behind the building over the weekend. But that same Saturday, Mother had promised to visit me at a pioneer camp five hours away, so she asked to be excused. The chairman refused, but my mother went anyway.

In the feud that followed her disobedience, Mother stood little chance. Her students started to receive low grades from the chairman even when they played perfectly, criticized for their “non-Mozartian” sound. Her credentials as a pianist were questioned: she hadn’t studied in a conservatory, graduating from the music faculty of a local institute. Her arrivals and departures were tracked with great diligence. Once, when the trolleybuses had stopped running because of a citywide power outage, Mother ran the remaining stretch through the First-Of-May Park, muddy after rain, with her high-heeled shoes in her hands. Any tardiness was seized upon and entered into her growing personnel file. The reports kept coming: “Wore red when everyone was ordered to wear black,” “Showed no enthusiasm during the open-door Party assembly,” “Has not performed at the holiday concert.” Reveling in the downfall of a former favorite, other colleagues eagerly supplied criticisms.

At home, Mother cried. Grandfather, who was still alive at the beginning of the ordeal, and whose one call to the Provost could have ended everything, chose not to interfere. Instead, he instructed Mother to “fight scum,” so that when he died, she’d know how to stand up for herself.

So she fought, and I watched. Her limited arsenal of weapons included perfect attendance at the annual Marxism-Leninism seminars for ideological workers; character references from the over-thirties club and from the TV station; oral testimony from sympathetic colleagues. At the concert for Lenin’s birthday that year, she and a jazz pianist who had just started at the department banged out Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on adjacent pianos, without the score. The audience, woken out of the lethargy of routine Chopin concertos and boilerplate revolutionary songs, went wild, and so they riffed on Bernstein and Copland for another half-hour. Everyone could see how good my mother’s playing was.

For a while, her renewed affair with the piano buoyed her spirits, but the feud dragged on, sucking the joy from our family life, already overshadowed by Grandfather’s death in 1983. Eventually, Mother fell ill, developing a blood clot in her shoulder that the doctors attributed to overexertion. They advised her against further piano practice. While she was in the hospital, I stayed with the family of a classmate, Valya. His father worked at the Trade Department of the regional Party Committee, so they lived a dream life, with a fridge full of hard-to-get foods and a white Lada Model 6.

From this hopeful quarter, help finally came. When Valya’s father picked Mother up from the hospital, her arm still swollen and blue from the blood clot, she confided her fear of being fired from her job at the Institute of Culture on grounds of “professional unfitness.” He asked for details, then later made sure he bumped into the Institute’s Provost in the corridors of the Party Committee building.

A “signal” from the Party Committee was no joke. A department meeting was convened at the Institute, during which the evidence was reviewed, the piano department chairman reprimanded, and my mother confirmed for another five-year term. But that victory, which might or might not have made Grandfather proud, only underscored our vulnerability. Despite its lowly status, the position of a senior pianoforte teacher was sought after by many who stubbornly refused to work at plants or on collective farms and enrolled, instead, in Institutes of Culture; and then they all needed jobs after graduation. So, Mother started attending professional development courses in Leningrad, the USSR’s “culture capital,” and there she formed the notion of studying for a doctorate. Music theory tracks were impossible to get into, so after bouncing around various departments, she ended up with a concentration in “organized family leisure.”

Suddenly, stacks of cheap yellow paper filled our apartment, along with brochures with titles like “The Role of District Party Committees in Constructing Village Culture” or “Communist Party Leadership in Organizing Reading Huts.” As I would get ready for bed, Mother would pull out a folding table and spread her papers over it; by morning, the table would be back in its place between the couch and the window. On every vacation, including to the Black Sea, the stacks of paper came along, too—carted about the way other people would carry their beach gear.

Still, she had to pay her way, and her options for income were limited. She could no longer give piano lessons because it aggravated her arm. But seamstressing work, another of her perennial money-making activities, was fairly safe: the sewing-machine motor was pedal-operated. And whereas the doctorate held only the promise of future gain, sewing brought concrete rewards in the present: ten rubles for a skirt, fifteen for a dress, twenty-five or thirty for a suit, depending on its complexity. As she hunched over her whirring Veritas machine and I over my homework, the reek in my nostrils of the hot iron she used to press down seams, my back against the edge of an improvised ironing board whose other end rested on the closed piano, I hoped she wouldn’t give up on her doctorate. She did not.

Meanwhile, I learned typewriting, including how to fix typos with the corner of a Neva razor and how to strike the keys with enough force to produce two carbon copies in addition to the original. And I got used to Mother’s comings and goings to Leningrad. By the time I was in the eighth grade, she agreed I could stay home alone, instead of with a classmate, when she went to the city.

Other things were changing, too. Brezhnev had died in 1982, and two more General Secretaries, Andropov and Chernenko, followed him in quick succession. A new one, Gorbachev, was different. He actually got out of his armor-plated limousine and walked the streets—with his wife!—shaking hands with people, even allowing them to criticize him. This was unheard of. Everybody talked about perestroika (reform) and glasnost (openness). TV broadcasting no longer shut down at midnight, but ran a slew of late-night shows that questioned and mocked the way we lived.

At the Leningrad Institute of Culture, things were picking up. Mother’s new doctoral supervisor was a professor of Culturology of some renown. He had an un-Russian name, Mark Lyutzievich, and spoke with the cultured accent of the Leningrad intelligentsia; by and large, he treated my mother kindly. But every man has his weakness. “My granddaughter,” he would say to my mother over the phone on the eve of her trip to Leningrad, “doesn’t believe me that in the South, walnuts get as big as human fists.” Mother would hang up and set off on a foraging expedition, looking for the mythic walnuts. In the seven years of her doctoral studies, she carried to Leningrad scores of boxes and bags of nuts, heirloom tomatoes, cherries, honeycombs. All for the precious granddaughter.

Finally in 1990, a week before Mother’s defense of her thesis, the professor let it be known that his granddaughter wanted fresh fish (Leningrad had only frozen). By then, it was late October, and even in our southern ponds, the perch and carp had already gone to the bottom, away from unshaven men in rubber boots who would net them and toss them into foul-smelling barrels, then scoop them out for customers with long-poled nets. Somehow, she managed to find a fish tank on the outskirts of town, and on my return from school that day, I encountered three apathetic carp and one lithe perch circling our half-filled bathtub, into which Mother had dropped small chunks of bread.

I did my best to ignore their doomed nibbling as I brushed my teeth, resenting their takeover of our tub, the smell of river mud they brought, and the fact that my mother would have to carry them all the way to Leningrad on a three-hour airplane flight, only to be sacrificed on the altar of Culturology. For years, the image of the glassy-eyed creatures swimming in our tub haunted me when I showered, along with an irrational fear of finding fish-scales on the soap.

In the morning, she wrapped the four limp fish in damp sheets of Soviet Culture and stuffed them into an oilskin hamper. It leaked, but the trolleybus taking us to the airport was empty at that early hour, so no one noticed. She carried the hamper in one hand and her suitcase in the other, while I bore her portable typewriter.

The defense was a breeze. Mother passed with flying colors.

The following year, the USSR collapsed. Gorbachev was out. Soon, the transition from a planned economy to a free-market one brought all sorts of unplanned consequences. By the time Mother received her first 345-ruble paycheck, a sum that had seemed astronomical to us at the start of her doctorate studies, it was worth a quarter of what she used to make as a senior pianoforte teacher without a doctorate, and getting less by the week. Meanwhile, fabric, a staple product that was immune from shortages in the old planned economy, had now disappeared from stores, and with it, her sewing clients. The old Veritas machine stood silent.

“Don’t worry about it,” Mother told me one day when I came home from the university and saw her staring out the window, an unlit cigarette in hand. “Nothing can be worse than what we had before.”