Arthur Schlesinger Jr. first met Robert F. Kennedy during Adlai Stevenson’s second run for the White House, in 1956. Schlesinger had been one of Stevenson’s senior advisers, while Kennedy, with his father’s connivance, had been an apprentice of sorts, tagging along and picking up pointers on how to run—and not run—a national presidential campaign. This was something Bobby’s old man figured might come in handy, and soon. “A long, rather sullen and ominous presence,” was how Schlesinger later described young RFK. “Kennedy and I regarded one another with great suspicion and barely spoke.”

Schlesinger didn’t mention their encounter in his journals. That mammoth chronicle, over which he labored for decades and which now takes up ample shelf-feet at the New York Public Library (the published version from 2007, edited by two of Schlesinger’s sons, represents only a tiny fraction of the original 6,000 pages), had not yet begun in earnest. That started—fittingly, given Schlesinger’s fascination with power—only around 1960, when the Harvard historian finally went with a winner: Senator John F. Kennedy, who brought Schlesinger into his circle, and then into his administration, for his Harvard pedigree, intellectual heft, and stalwart liberal credentials. Only then were there matters of moment to record, at least some of them involving Schlesinger himself. And because they’ve scarcely been mined, for anyone writing about Robert F. Kennedy—in my case, for a book about his relationship with Martin Luther King Jr.—the journals offer a ready source of insightful, clever, catty, and original material.

Bobby Kennedy was plenty important to his brother, first running his campaign, then becoming his Attorney General. But judging from the paucity of entries mentioning RFK, Schlesinger was slow to notice or care. Perhaps the old skepticism, and resentment, lingered. Or maybe, he remained unimpressed: Schlesinger had his snobbish side, and even when Bobby became a person of consequence, he remained in Schlesinger’s eyes less charming, dazzling, sophisticated, intelligent, and good-looking than his big brother. As a journal entry from January 1965 makes clear, Schlesinger (who’d gone to Harvard with Joseph Jr., killed during World War II) felt Joe and Rose Kennedy had reaped ever-diminishing returns from their surviving successive sons. “Teddy is a fine fellow, but he is much further below Bobby in ability than Bobby is below JFK,” he wrote.

But over the next three and a half years, something dramatic happened. As Robert Kennedy grew, Schlesinger’s affection, respect, and admiration for him grew, too. No doubt, this reflected Schlesinger’s own needs: after a career in the backwaters of Cambridge, Schlesinger was seduced by the power and glamour of Washington, D.C., and Bobby Kennedy provided him with an entrée back into the world of influence that had been so suddenly and cruelly wrested from him by what RFK always called “the events of November 1963.” But it wasn’t only that. As so many others eventually did, including many normally world-weary journalists, Schlesinger fell for Robert Kennedy.

More improbably, though, Schlesinger also came to respect Bobby—more, even, than he had respected his older brother. “It will be a long time before this nation is as nobly led as it has been in these last three years,” he’d written, in shock and sorrow, on November 22, 1963. But only four and half years later, he had changed his mind.

*

Bobby Kennedy first appears, then, in Schlesinger’s journals in July 1959—as a thorn in his brother’s side. The subject was Senator Joseph McCarthy, and the flak the presidential nominee-to-be was taking for how slowly he’d disowned the notorious Red-baiter. Constraining him, he explained to Schlesinger, was Bobby’s notorious decision to work for McCarthy in the early 1950s—a move that Joe Kennedy had engineered but that Jack Kennedy had opposed.

The Bobby Kennedy whom Schlesinger watched preside over a staff meeting during the Democratic Convention in July 1960 was tough but surprisingly progressive. Bobby stressed the Kennedy campaign’s commitment to a strong civil rights plank, then warned anyone tempted to head off to Disneyland for the day to tell him beforehand “so he could get someone else to do their job.” All this shifted Schlesinger’s perception of the man, though only, at first, from contempt to condescension. “It was a fairly impressive performance, not without its charms,” he wrote.

Curiously, though perhaps because his own interests lay more in foreign affairs, Schlesinger wrote nothing about Kennedy becoming Attorney General, a move that was much criticized by others. In 1961, on the eve of the Bay of Pigs fiasco, it was Bobby’s loyalty to his brother, as well as his spirit and style, that registered more with Schlesinger than his intellect or policy positions. “You may be right or you may be wrong, but the president has made his mind up,” RFK had told Schlesinger when Schlesinger voiced doubts about the impending operation. “Now is the time for everyone to help him all they can.”

Advertisement

Bobby was more impressive than he’d first seemed, and more likable, but was still, at least to Schlesinger, a bit primitive. As the entry for April 12, 1961, relates:

In the evening we went to Bobby Kennedy’s for a large Irish birthday party for Ethel. It was a messy, disordered, chaotic party, always trembling on the verge of total disintegration, but somehow held together by the raucous high spirits of the company. After dinner there were skits—Ethel taking off, Bobby going to work, etc. In certain respects it was a terrible party, but it was also tremendous fun. One can imagine no greater contrast than with the party the President gave at the White House a month ago. That was chic, decorous, urbane; this was raffish, confused, loud—Brockton [Massachusetts] rather than Hobe Sound [Florida].

At a White House dinner dance that year, Schlesinger witnessed another display of Bobby’s fraternal feeling—and of his fabled combativeness. “Gore Vidal got in violent fights, first with Lem Billings and then with Bobby,” he wrote, and went on:

According to Gore, Bobby found him crouching by Jackie and steadying himself by putting his arm on her shoulder. Bobby stepped up and quietly moved the arm. Gore then went over to Bobby and said, “Never do anything like that to me again.” Bobby started to step away when Gore added, “I have always thought you were a god-damned impertinent son-of-a-bitch.” At this, according to Gore, Bobby said, “Why don’t you get yourself lost?” Gore replied, “If that is your level of dialogue, I can only respond by saying: Drop dead.”

On December 10, Schlesinger attended what would become known, after the name of the Robert Kennedys’ northern Virginia estate, as the Hickory Hill Seminars: lectures on various weighty topics that Bobby and his wife, Ethel, organized. But what stuck with Schlesinger from that night wasn’t the subject at hand but a conversation he’d had with Ethel about Billy Wilder’s latest film, One, Two, Three. “Ethel added that she thought the film almost un-American,” he recalled. “The Kennedy Catholicism comes out in odd and unexpected ways. Ethel is really deeply Puritanical and mistrustful of satire and irreverence.” It bespoke a clinical, almost anthropological detachment from the Kennedys that later disappeared from Schlesinger’s journals.

Some of that same priggishness, he later suggested, was also apparent in Ethel’s husband. “Bobby called me on Thursday to ask me about The Memoirs of Fanny Hill,” Schlesinger recorded in June 1963. Acting in his capacity as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer, Kennedy was “disgusted by the book,” he noted, “but reluctant to proceed against it.” The dutiful Schlesinger set out to learn whether the book was “defensible in any historical and literary sense”—first, presumably, by reading it himself, and then by enlisting Edmund Wilson and Howard Mumford Jones for their expertise. “Edmund had declined to write a preference for it, but said that, while a designedly pornographic work, it was so much less filthy than the recently published books like The Naked Luncheon [sic] and City of Night, that he thought it would be foolish to attack it,” Schlesinger recorded.

But whatever its literary merits or demerits, Schlesinger thought the book would make a swell birthday present for the head of the United States Information Agency, Donald Wilson, at a party held on the Kennedys’ yacht. “Bobby did not think it was funny,” Schlesinger recalled. “Before the evening was over, he hurled the book into the Potomac.” (For unexplained reasons, the rampaging attorney general also tossed overboard several bottles of champagne.)

Schlesinger’s growing closeness with Robert Kennedy becomes apparent during an incident at another party, in June 1962, when, during an evening of antics at a dance honoring the British actor (and brother-in-law to Jack and Bobby) Peter Lawford at Hickory Hill, someone nudged Schlesinger and he, in his light blue dinner jacket, fell into the pool. (It made the front page of the New York Herald Tribune.) “I found that Bobby’s clothes fitted me perfectly and stayed till five,” Schlesinger wrote. After that, the mandarin remarks about Bobby’s bad taste, such as a September 1962 slap at his “garish” office at the Justice Department, tapered off.

Just when Schlesinger first deemed Bobby Kennedy presidential timber is not apparent—with Jack so entrenched, why even think about such things?—but others already did. In January 1963, Schlesinger was at the National Archives to mark the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, and to hear the attorney general give an address on the subject that Schlesinger had originally written for JFK to deliver in Palm Beach a few days earlier, before saner heads realized that marking manumission from a venue in the segregated South would have been a political faux pas. “It was a good speech, and, at the end, Joe Rauh passed me a note saying ‘Poor Lyndon,’” Schlesinger wrote. “I asked Joe what he meant. He said, ‘Lyndon must know he is through. Bobby is going to be the next President.’” Months later, Schlesinger also noted Bobby’s trajectory. As he recorded that April:

Advertisement

On Wednesday night I attended Marie Harriman’s birthday party—a most agreeable occasion. Among those present were FDR Jr., Randolph Churchill and Bobby Kennedy—an unusual representation of the great dynasties of the twentieth century. The dominating figure of the three, it must be said, was Bobby, who kidded the others mercilessly. He had, of course, the moral advantage of being on the way up while both of them had a consciousness of spoiled and wasted lives.

Part of that night’s discussion concerned the upcoming World’s Fair in New York, which fell under Roosevelt Jr.’s jurisdiction as Undersecretary of Commerce; Bobby Kennedy warned FDR Jr. that he, Roosevelt, would be held accountable for whatever went wrong. (“Franklin said to me later, ‘He’s just nasty enough to mean that, too,’” Schlesinger noted without comment.) But a few weeks later, when a superannuated Felix Frankfurter droned on embarrassingly at a swearing-in ceremony, prompting some guests to stray, Schlesinger spotted something in Robert Kennedy that many missed: tenderness. “If that experience gave the old man half an hour of pleasure, no one in the room had such pressing business that he couldn’t have stayed for a few extra minutes,” Kennedy remarked to him when it was over.

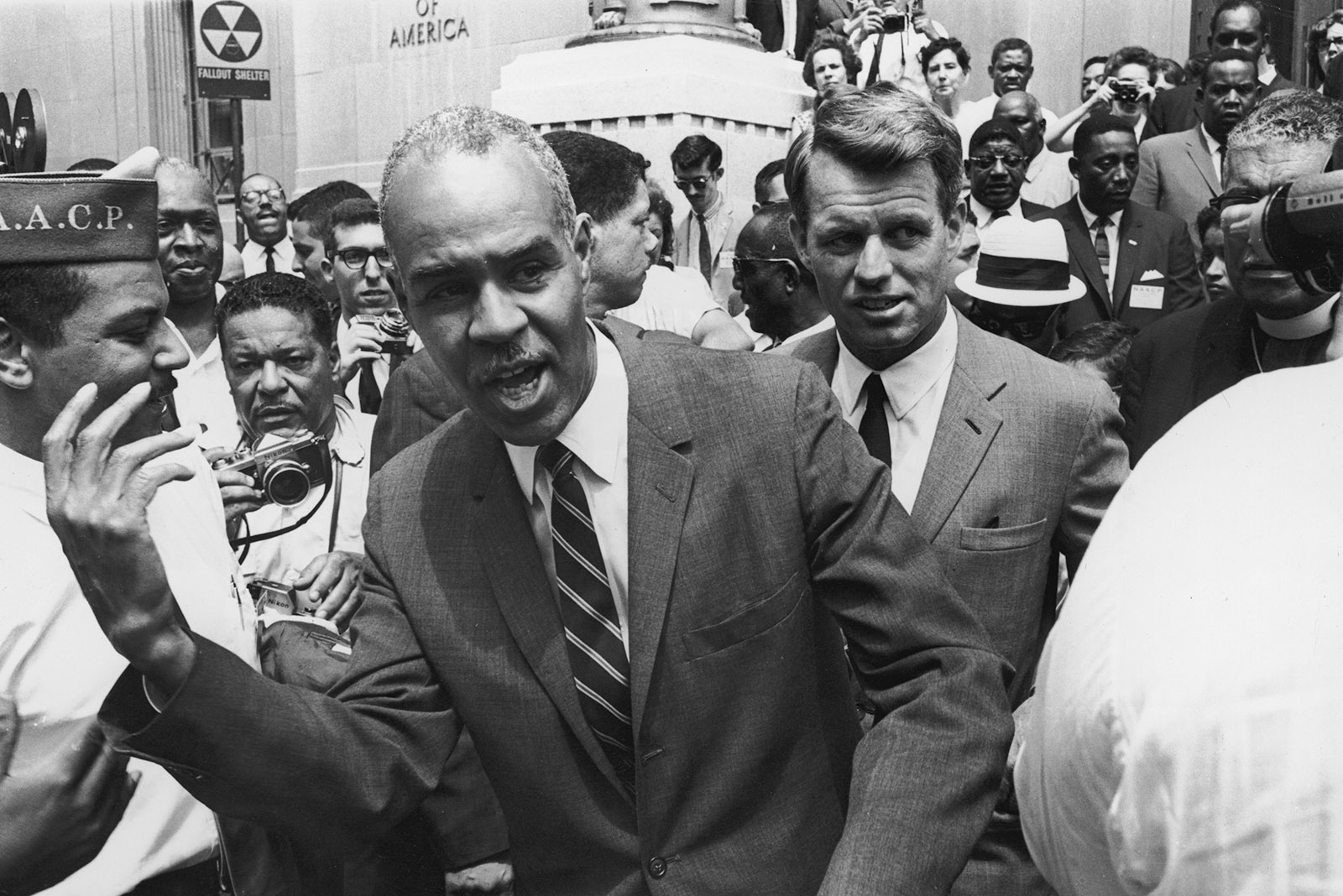

In June 1963, a few days after James Baldwin and assorted other black artists and intellectuals (Harry Belafonte, Kenneth Clark, Lorraine Hansberry, and Lena Horne among them) famously berated Bobby Kennedy about the Kennedy administration’s civil rights record at a private gathering at Joe Kennedy’s New York apartment, it was to Schlesinger that a put-upon RFK fumed. Far more than his brother ever did, Bobby Kennedy—curious, adventurous, and, at times, even reckless—ventured into the most hostile precincts of the black community, high and low, the salon and the street. But when things inevitably turned rancorous, he would pout, feeling unappreciated and resentful.

“They didn’t know anything,” Kennedy complained. “They don’t know what our laws are—they don’t know what the facts are—they don’t know what we’ve been doing or what we’re trying to do… It was all emotion, hysteria—they stood up and orated.” (At one point, Schlesinger related, “the lovely Lena Horne” had said, “Mr. Attorney General, you can take all those pious statements and stuff them up your ass.”)

“All of this was a great shock to Bobby, who sees himself (correctly) as the Attorney General who has labored hardest for Negro rights in our history,” Schlesinger wrote. When word of the meeting appeared in the press, including on the front page of The New York Times—Kennedy blamed Baldwin for that—“Bobby had a feeling of ultimate betrayal,” Schlesinger added.

Yet Kennedy quickly calmed down. This was a familiar pattern with him: pique, then reflection, then remediation. Three weeks later, largely under Bobby’s coaxing, Jack Kennedy delivered one of his greatest speeches, calling for racial understanding and sweeping civil rights legislation.

Within five months, the Kennedy era was over. What Schlesinger, who often put off his journal entries, witnessed on November 22, 1963, he described that same day: for once, he was recording, rather than reassembling, history. His entry for 5:15 AM on November 23 described the arrival of the president’s remains in the East Room only a few hours earlier, and how Robert Kennedy had asked him and the White House’s social secretary, Nancy Tuckerman, whether the casket should be opened or closed. “So I went in, with the candles fitfully burning, three priests on their knees praying in the background, and took a last look at my beloved President, my beloved friend,” wrote Schlesinger. “For a moment I was shattered. But it was not a good job; probably it could not have been with half his head blasted away. It was too waxen, too made up. It did not really look like him. Nancy and I told this to Bobby and voted to keep the casket closed.” There was precedent, Schlesinger offered, as surely only Schlesinger, among those close at hand, could have: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s casket had also been closed. Bobby concurred.

Later that day, Schlesinger received an assessment from McGeorge Bundy of the post-assassination state of Robert Kennedy. “He [Bundy] said that he worried about Bobby, that Bobby was reluctant to face the new reality, that he had virtually to drag Bobby into the cabinet meeting and that, if Bobby continued in this mood, he had probably better resign,” Schlesinger recorded. For months to come, Robert Kennedy, consumed with grief, would remain largely out of commission. And yet, the political calculations soon resumed, with Schlesinger ever ready with advice—when he wasn’t stirring the pot himself.

Thus, on December 5, flying back from Boston on the Kennedys’ private plane, the Caroline, following the incorporation of the new John F. Kennedy Library, Bobby asked Schlesinger whether he, Bobby, should go for the now-vacated vice-presidency. As Schlesinger recorded:

My first reaction was negative, though, when he asked me why, I found it hard to give clear reasons. I think, first, that it seems to me a little too artificial and calculated; second, that Bobby should develop his own independent political base; and third, that LBJ might well prefer [Sargent] Shriver on the ground that Shriver would bring along Bobby’s friends without bringing along his enemies. Bobby added that he did not like the idea of taking a job which was really based on the premise of waiting around for someone to die… I made clear that I hoped he would be President some day and wanted to do what I could to bring this about.

Schlesinger advised Kennedy to stay at the Justice Department for “an appropriate period,” then go into private life, devoting himself to the sort of humanitarian work that would “erase the national impression that he was a demonic prosecutor.” (Repairing Kennedy’s reputation for ruthlessness became a Schlesinger obsession.) Or he could buy the cash-strapped New York Post, then still a major liberal voice. He could also run for governor—of either Massachusetts or New York. “Bobby obviously has no confidence in and no taste for Johnson and obviously wants to be President himself (an ambition I thoroughly applaud and will support),” wrote Schlesinger.

And Kennedy’s appeal was apparent. Schlesinger was with him in December 1963 when he exited Temple Emanu-El in New York, following the funeral of former Governor Herbert Lehman, and made his way down Fifth Avenue. “The bystanders broke into spontaneous applause at the sight of Bobby,” he wrote. “It was touching.” For the next eleven months, though, Kennedy told him, he’d stay at the Justice Department, seeing through his brother’s civil rights bill, then participating in the presidential campaign.

Whether or not Schlesinger exaggerated his closeness to the Kennedys, he was surely one of the few who could discuss the assassination of JFK with Bobby. “I asked him, perhaps tactlessly, about Oswald,” he related. “He said that there could be no serious doubt that he was guilty, but there was still argument whether he did it by himself or as part of a larger plot, whether organized by Castro or by gangsters.” Later on, he asked Kennedy about the Warren Commission report. “It is evident that he believes that it was a poor job and will not endorse it, but that he is unwilling to criticize it and thereby reopen the whole tragic business,” Schlesinger noted.

Kennedy vowed to Schlesinger that December to maintain an underground of Kennedy loyalists in Lyndon Johnson’s increasingly hostile Washington. He told Schlesinger:

We worked hard to get where we are, and we can’t let it all go to waste. My brother barely had a chance to get started—and there is so much now to be done—for the Negroes and the unemployed and school kids and everyone else who is not getting a decent break in our society. This is what counts. The new fellow doesn’t get this. He knows all about politics and nothing about human beings.

Schlesinger, naturally, was all in. “I am more and more persuaded that he should go for the Vice Presidency—and more and more persuaded that I am for him whatever he wants,” he wrote. (Kennedy’s precise course mattered less to Schlesinger than that he remain in play.) A few days later, when Kennedy fantasized about becoming Secretary of State (with Shriver as vice-president), Schlesinger remained unwaveringly loyal: “This would, of course, be wonderful,” he wrote. In the new White House, though, Johnson had little use for Schlesinger. In late January, he quit, and began writing his book on the Kennedy presidency.

But with his vast network—Schlesinger’s circle of close friends resembled Weegee’s famous photograph of a summer Sunday on Coney Island—Schlesinger remained Bobby’s confidant and booster. Once “Lyndon Johnson,” as Kennedy invariably called him, with a formality that underlined their estrangement, had spurned him for the second spot—the president, as Kennedy put it, didn’t want “a cross little fellow looking over his shoulder”—he sought Schlesinger’s advice again. With the help of former Kennedy speechwriter Dick Goodwin, Schlesinger decided that his long-time mentor, Adlai Stevenson, should run for the Senate from New York, and “LBJ should be persuaded to appoint Bobby to the UN,” he wrote in an entry for July 18, 1964, going on to observe:

This would have several advantages. It would put Bobby in touch with the questions which engage him most; it would utilize the Kennedy name and tradition at a point where it could serve US interests most effectively; it would keep Bobby in the administration but away from Washington; it would enable him to establish a political base in New York; and it would help kill the public impression of him as the ruthless prosecutor.

By August, the talk had returned to making Bobby Secretary of State, but Kennedy was increasingly inclined to run for Senate in New York. For Schlesinger, that posed a problem since Stevenson did indeed fancy the seat. Over dinner at Katherine Graham’s house in Georgetown and later, walking Stevenson over to Averell Harriman’s, Schlesinger sounded out him on the subject. Stevenson soon demurred; Kennedy ran and won—which, by then, Schlesinger had decided was the desirable result. “His mood is excellent,” he wrote of Kennedy on Inauguration Day, 1965. “He said he thanked heaven every day that the Vice-Presidency had fallen through. He loves traveling around New York and says that what he would really like some day is to become Governor.”

Temporarily sidelined from presidential politics, solidifying his tenuous ties to New York, Kennedy evidently held little interest for Schlesinger for the next year or so. But by March 1966, Vietnam clouded many political futures, Kennedy’s among them. Preparing RFK at Hickory Hill for Face the Nation, Schlesinger warned he might be asked how his brother would have handled things there. “Bobby ruminated a moment and said, ‘well, I don’t know what would be best: to say that he didn’t spend much time thinking about it; or to say that he did and messed it up,’” Schlesinger wrote. “Then, in a sudden, surprising gesture, he turned to the sky, thrust out his hand, and said, ‘Which, Brother, which?’”

Though it’s difficult to disentangle the two, Schlesinger’s regard for Kennedy rose in tandem with Kennedy’s prospects. “My respect for his intelligence, honesty, and openness of mind grows all the time,” Schlesinger noted. In fact, after huddling with John Kenneth Galbraith and George McGovern at Galbraith’s house in Vermont in late July, Schlesinger began contemplating a Kennedy candidacy in 1968. He knew the long odds of ousting an incumbent president as well as anyone—“Someone reminded me of the message Harry Truman gave to Paul Porter in the spring of 1948: ‘Tell your ADA [Americans for Democratic Action] friends that any shit sitting behind this desk can win his own re-nomination”—but with the unabated guilt and sorrow over JFK, plus LBJ’s unpopularity, plus the deepening quagmire in Vietnam, plus Kennedy’s appeal to the young, maybe, Schlesinger felt, it wouldn’t be impossible. As he wrote:

He has been extremely impressive in these months. He has exposed himself to a series of unpredictable situations—South Africa, Mississippi and Alabama, Vietnam, foreign aid, the Negro revolution—and has not, so far as I can see, set a wrong foot. And he does this primarily, so far as I can see, on his own instincts… The Machiavellian myth of RFK—the notion that he is a rigorous and premeditated calculator of chances and opportunities—dies hard. But, in fact, he is a fatalist, who has determined to be the best senator he can and do what he thinks is right.

Any lingering suspicion that Bobby Kennedy was an intellectual lightweight waned. During a visit to Hyannis Port in August 1966, for instance, RFK showed Schlesinger what he was reading—Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way. Then, “almost shyly,” he pulled out a well-thumbed paperback called Three Greek Plays, and asked Schlesinger to read two selections from The Trojan Women, one on the horrors of war, the other on friendship and loyalty. And, as early as November 1966, Schlesinger also credited him with having “the best political brain in America.” Still, Schlesinger thought Kennedy believed his year would be 1972, not 1968.

In a pair of visits to Hickory Hill in the spring of 1967, though, Schlesinger encountered a visibly demoralized man—convinced that criticizing Johnson on Vietnam only spurred the president to dig in there more deeply, while raising questions among Kennedy’s many skeptics about his own motives. “But how can we possibly survive five more years of Lyndon Johnson as President?” he asked Schlesinger. “Five more years of a crazy man?”

*

Schlesinger was back at Hickory Hill in late September when “Dump Johnson” movement founders Allard Lowenstein and Jack Newfield tried to convince Kennedy to take on LBJ. By October, Schlesinger himself was advising Kennedy not to delay getting in the race, warning that were Senator Eugene McCarthy to do so first, he would “make himself the hero and leader of the antiwar movement and cast RFK as a Johnny-come-lately.” During a “council of war” in December—by which point McCarthy had announced his candidacy—Schlesinger, along with Goodwin, Pierre Salinger, and others, again urged him to run. “I do not think I have ever seen Bobby so torn about anything,” Schlesinger noted. It would be months before Kennedy reached his final decision.

Indeed, in February, as the Tet offensive raged in Vietnam, Kennedy announced he would not run. Ten days passed before the seemingly deflated diarist could rouse himself to write anything. McCarthy’s success in the New Hampshire primary on March 12, when he very nearly defeated Lyndon Johnson (who was not formally on the ballot, but had nevertheless been expected to win easily as a write-in candidate), weakened Kennedy’s prospects still further. By this point, even Schlesinger opposed Kennedy’s entry into the race. But after yet another huddle at Hickory Hill—the very place, Schlesinger mused, where he and other Kennedy aides had discussed the impending Cuban invasion seven years earlier—Kennedy defied their advice and plunged into the race. “I shuddered and prayed that this would not be Bobby’s Bay of Pigs,” Schlesinger wrote.

Schlesinger was in Kennedy’s New York apartment on March 31 when Johnson withdrew from the race. “The mood was one of astonishment, a certain perplexity and a general, non-exuberant, incredulous feeling that RFK would be our next president,” he wrote. Two nights later, he was watching the returns from the Wisconsin primary at Vogue editor Diana Vreeland’s apartment when Jacqueline Kennedy approached him. “Do you know what I think will happen to Bobby if he is elected President? The same thing that happened to Jack,” she told him. “There is so much hatred in this country, and more people hate Bobby than hate Jack. That’s why I don’t want him to be President. I’ve told Bobby this, but he is fatalistic, like me.”

Schlesinger even stumped for Kennedy, in Indiana, California, and Michigan, all the while marveling at the antipathy Bobby generated—just as Jackie had observed. (A deep-seated Kennedy-hatred, in remission since November 1963, had resurfaced.) Schlesinger also came to realize that this vituperation, fueled by the enthusiasm among the elites for the candidacy of the idealistic antiwar Gene McCarthy, was now pouring over onto him, too—as he noted:

I guess I have never been much liked by the New York literary people—the Lowells, Kazins, Epsteins etc.—though they’ve always accepted one’s hospitality in Cambridge and Washington (something never repaid here); and now the McCarthy hysteria has turned this into real hatred. Now I am hissed at practically every public appearance in this city. I have just been out to get the morning Times, and inevitably someone harangued and denounced me on Third Avenue—again a McCarthyite. I think these people are crazy.

Still, a nightclub dinner in September 1968 convinced him he wasn’t missing all that much:

Last night at Peter Duchin’s table at El Morocco, I got this nonsense at considerable length from Bob Silvers: Nixon is really not so bad, and he will get us out of the war in Vietnam sooner than anyone else! As Alexandra [Emmet Allan, whom Schlesinger would marry in 1971] said, anyone predicting a year ago that Silvers, Halberstam, and Barbara Epstein would be shilling for Nixon would have been considered loony. As I say, the ignorance/arrogance of New York intellectuals when it comes to politics is beyond belief.

Schlesinger also pitched in during the California primary. So devoted was he, in fact, that he returned to New York for an appointment, then flew back to San Francisco, in a single day. He watched Kennedy debate McCarthy on June 1, then returned to New York. On the day of the primary itself, June 4, he was in Chicago for a conference on Vietnam; Saul Bellow had invited him, along with Frances Fitzgerald, to watch the returns at his apartment. They stayed until it was clear Kennedy had won, and then the historian Richard Wade, who’d also been there, dropped him off at his hotel.

Schlesinger attempted to call Kennedy with his congratulations; the line was constantly busy. Hardly had he fallen asleep when the phone rang. It was Richard Goodwin. “Kennedy’s been shot,” he said.

At first, Schlesinger was inexplicably optimistic: the bullet, a specialist had said on television, had entered a part of the brain “that didn’t much matter.” He’d returned to Cambridge by the time William vanden Heuvel called to say Bobby Kennedy had died. Schlesinger was there when the plane bearing Kennedy—that extraordinary flight, with America’s three most famous widows, Ethel and Jacqueline Kennedy and Coretta Scott King, all aboard—arrived at LaGuardia Airport. “It was all too familiar,” he wrote. “The night was warm rather than cold; but the same sadness penetrated everything.” George Plimpton spotted Schlesinger in the crowd. “His face was puffed and utterly tragic,” he told the journalist Jean Stein. “That night was the first time I’d ever seen him without one of those perky [bow] ties of his. He was wearing a long black knit tie.”

As close as Schlesinger had become to RFK, he’d still misread him in one respect, at least. Nearly a year after the assassination, Schlesinger had lunch with the late senator’s long-time secretary, Angie Novello, as he recorded:

I said that I had always been nominally against capital punishment but that I saw no point in keeping Sirhan alive. Angie looked a bit shocked, shook her head and said, “Oh, no, Bob would not have liked that.” I asked her whether he was against capital punishment. She said, “Yes.” Then she added, “You know, if by any chance Bob had lived, no one would have been more forgiving of Sirhan.”

In the end, Arthur Schlesinger had come to know Robert Kennedy better than he’d ever known John. And sitting down with his journals three days after Bobby’s death, Schlesinger acknowledged that, to his own surprise, he’d grown closer to him, too. Hero-worshipper though he may have been, he retained—or now reclaimed—a historian’s powers of observation, and judgment. He dissected the differences between the two brothers as only he could have done.

JFK, one sensed, was always a skeptic and an ironist; he had understood the complexity of things from birth. RFK began as a true believer; he acquired his sense of the complexity of things from hard experience. He remained a true believer to the end but at a far deeper level; he had long since shucked away the eternal criteria and the received simplifications and got down as far as one can in politics to the human meaning of things. JFK attacked conditions because they seemed irrational, RFK because they seemed hateful. JFK was a man of cerebration; Bobby was very bright and reflective, but he was a man of commitment. If JFK saw people living in squalor, it seemed to him totally unreasonable and awful, but he saw it all, as FDR would have done, from the outside. RFK had an astonishing capacity to identify himself with the casualties and victims of our society. When he went among them, these were his children, his scraps of food, his hovels. JFK was urbane, imperturbably, always in control, invulnerable, it seemed, to everything, except the murderer’s bullet. RFK was far more vulnerable. One wanted to protect him; one never felt that Jack needed protection.

In Bobby’s case the contrast between the myth and the man could not have been greater. He was supposed to be hard, ruthless, unfeeling, unyielding, a grudge-bearer, a hater. In fact, he was an exceptionally gentle and considerate man, the most bluntly honest man I have ever encountered in politics, a profoundly idealistic man and an extremely funny man. JFK had much better manners. RFK was often diffident and had no small talk. He would do much better at Resurrection City than at the Metropolitan Club.

Schlesinger’s final comparison between the two was his most startling. “It will be a long time before this nation is as nobly led as it has been in these last three years,” he had written on November 22, 1963. But only four and a half years later, by the time Bobby Kennedy walked into the pantry of the Ambassador Hotel, Schlesinger had been prepared to say that time was already nigh. “What kind of a President would he have made?” he asked. “I think very likely a greater one than JFK. He was more radical than JFK; he understood better the problems of the excluded groups; and he would have been coming along in a time more propitious for radical action.”

“We have now murdered the three men who more than any other incarnated the idealism of America in our time,” he concluded. Never again, he vowed, would he let himself become so attached to a politician, and never did he.

In November 1968, Richard Nixon was elected president of the United States.