I was listening recently to a BBC radio documentary about the photographer and journalist Val Wilmer, who wrote a great book on the free jazz movement in the late 1970s, As Serious as Your Life (recently reissued by Serpent’s Tail). The title was taken from something the pianist McCoy Tyner said to her, explaining just how important music was to him. And Wilmer took that to heart, too, because her book is not only about musical form and expression, but also about the lives of musicians. It should be obvious that art and life are entangled, but for the first half of the twentieth century a bias toward formalism meant that jazz was seldom discussed in relation to the social, economic, and political struggles of those who played it. That changed in the 1950s with the emergence of left-wing jazz critics like Nat Hentoff and Eric Hobsbawm, writing for the New Statesman under the pen name Francis Newton, and, in the 1960s, critics influenced by the emerging black power movement, such as LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) and A.B. Spellman. But then, a no less misleading tendency developed, which was to analyze jazz, especially formally adventurous, “free,” or avant-garde jazz, as some kind of direct expression of radical politics: the cry of urban rage or the voice of the black revolution. Questions of aesthetics, of the painstaking choices that people made when crafting their art, went out the door, as if music were simply another form of protest.

Wilmer, to her credit, had (and has) great feeling for the aesthetics of jazz. She understood, moreover, that the relationship between art and life is a very complicated one, and that it is forged in struggle or, rather, struggles. She was describing jazz made in an era of civil rights and black power, but she didn’t confine herself to questions of race, and gave particularly sensitive attention to the marginalization of women in jazz. What’s more, she grasped that there is a struggle that precedes all others: the matrix in which other struggles are inscribed, which is simply the human struggle to go through life, to endure, and to make one’s mark, whatever that may be. One needn’t embrace a spurious universalism blind to race and gender, or to other forms of discrimination, to see that this struggle is our common one, even if we experience it in very different ways inflected by our backgrounds and experiences. The making of art is also a struggle, because it involves the creation of something that wasn’t there before; it is a giving birth.

In her BBC interview, Wilmer speaks of being incredibly moved when she first heard Ray Charles. What overwhelmed her were his cries of pain, which seemed to her more visceral than anything she’d ever heard in the white popular music she’d grown up with in England. The reason we’re so affected by singers like Charles, she goes on to say, is that they remind us of our experience in the womb. I’m more inclined to think that it’s the woman, rather than the child, who undergoes the agony of birth, but, in her somewhat mystical way, I think Wilmer is on to something. We’re moved by artistic expressions of pain, strife, suffering—and other, more joyous emotions—because, in their rawness of simulated emotion, they take us back to the earliest experiences of entering this world.

Of course, not every artist taps into this emotion directly. When you look at an Agnes Martin painting or listen to Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians—and these are both artists I admire greatly—your first reaction isn’t to be moved by the pain they evoke. But I wonder if, in their calm and ordered elegance, they might suggest an angle of repose, a kind of transcendence from the world’s turbulence: what Cecil Taylor, the great avant-garde pianist who died in April, called “the air above mountains.” They didn’t get there by flying to the top; to reach that place, they first had to climb the mountain; they had to struggle.

Lou Reed has a wonderful line in the Velvet Underground song “Some Kinda Love”: “between thought and expression lies a lifetime.” Not just a lifetime, but a history, and a relationship to the larger forces of history. History isn’t a stage; it’s the air we breathe. It enables us, and traps us. It gives us life, and takes it away. I’ve often written about that place between “thought and expression” in the work of musicians and artists, practicing a biographical approach to criticism that is sometimes held in contempt, particularly in the academic world. It’s considered a bit lowly, partly because it’s often done poorly, in the form of facile psychologizing, partly because people’s lives are invariably messier than the work they produce. Art, we’re told, can’t be reduced to the life, which is very evidently true; or increasingly, we’re told that if an artist is a less than exemplary person—or, worse, a sexual predator—the art is no longer of value. This is a position that seems equally troubling to me, since we thereby deny ourselves a lot of valuable work, while flattering ourselves that we’re somehow virtuous for doing so. No question, we have to proceed cautiously in examining the lives of artists—really, of anyone. As James Wood nicely puts it in an essay on W.G. Sebald, “Because we are not God, our narration of another’s life is a pretense of knowledge—simultaneously an attempt to know and a confession of how little we know.”

Advertisement

So, we have to be humble; we have to own up to the limits of our knowledge. We also have to ask ourselves: Why are we telling this particular story? Why, to take an example of someone I wrote about recently in the Review, are we so fascinated by the story of a composer who died nearly three decades ago in obscurity, a drug-addicted homeless man who spent his last days in Tompkins Square Park, close to starvation? I’m speaking of Julius Eastman, whose music is enjoying an extraordinary revival today. (Actually, revival isn’t the word for the hysteria surrounding Eastman’s work, because that implies rediscovery and this is really a discovery.) It seems to me that if we don’t examine the roots of this fascination, we end up obfuscating the story and creating a legend, a mythology, instead—in this case, the tale of a saint, brought down by the forces of social convention, power, racism, etc. Don’t get me wrong: Eastman battled throughout his life with racism and homophobia. He had a fascination with Joan of Arc, and was enthralled by the idea of martyrdom, hoping that he, too, might die for the cause of gay liberation. He gravitated to everything spiritual, and spiritualized everything he did, including his more hedonistic endeavors. If he were alive, he might very well be pleased by the canonization.

But it is one thing to say that Eastman was fascinated by heroism, and another to say that he lived his life as a hero, which is the impression left by some of the recent commentary about him. If you go along with that view, you’re missing the great sadness of this story, the struggle that he undertook not only with society but, more intimately, with himself.

Those who knew Eastman well all speak of this waste of potential, the fact that he succumbed to his demons and drifted away—of his own volition—from what was a very promising career. This is a story of refusal of society’s categories, and there’s something brave and daring about it. But it’s also a story of fragility, deterioration, addiction, and, perhaps, of mental illness. Part of Eastman’s difficulty, to be sure, was that the avant-garde, particularly in classical music, was always defined as always already not-black, as the cultural theorist Fred Moten has argued. But this was not Eastman’s only source of difficulty.

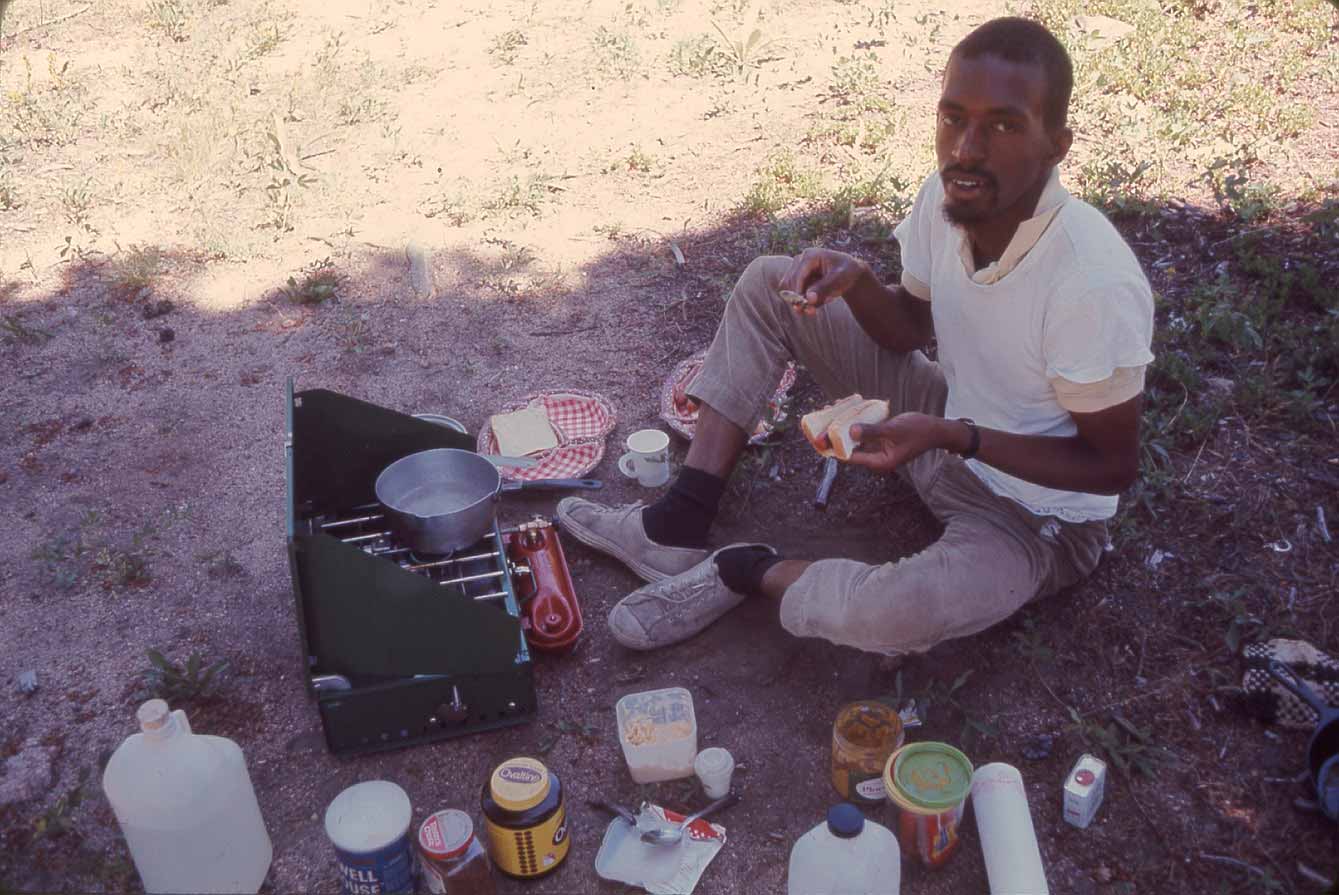

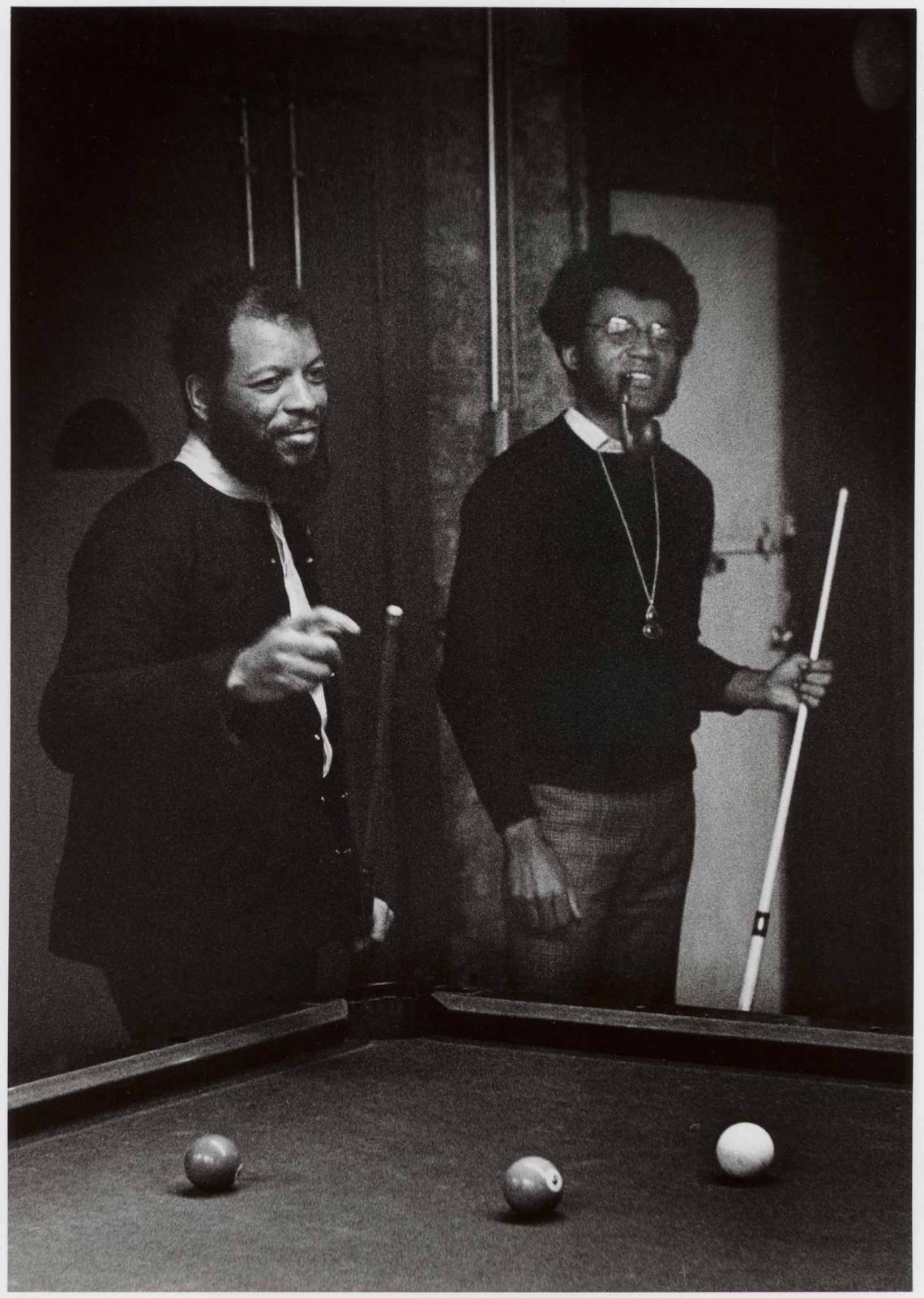

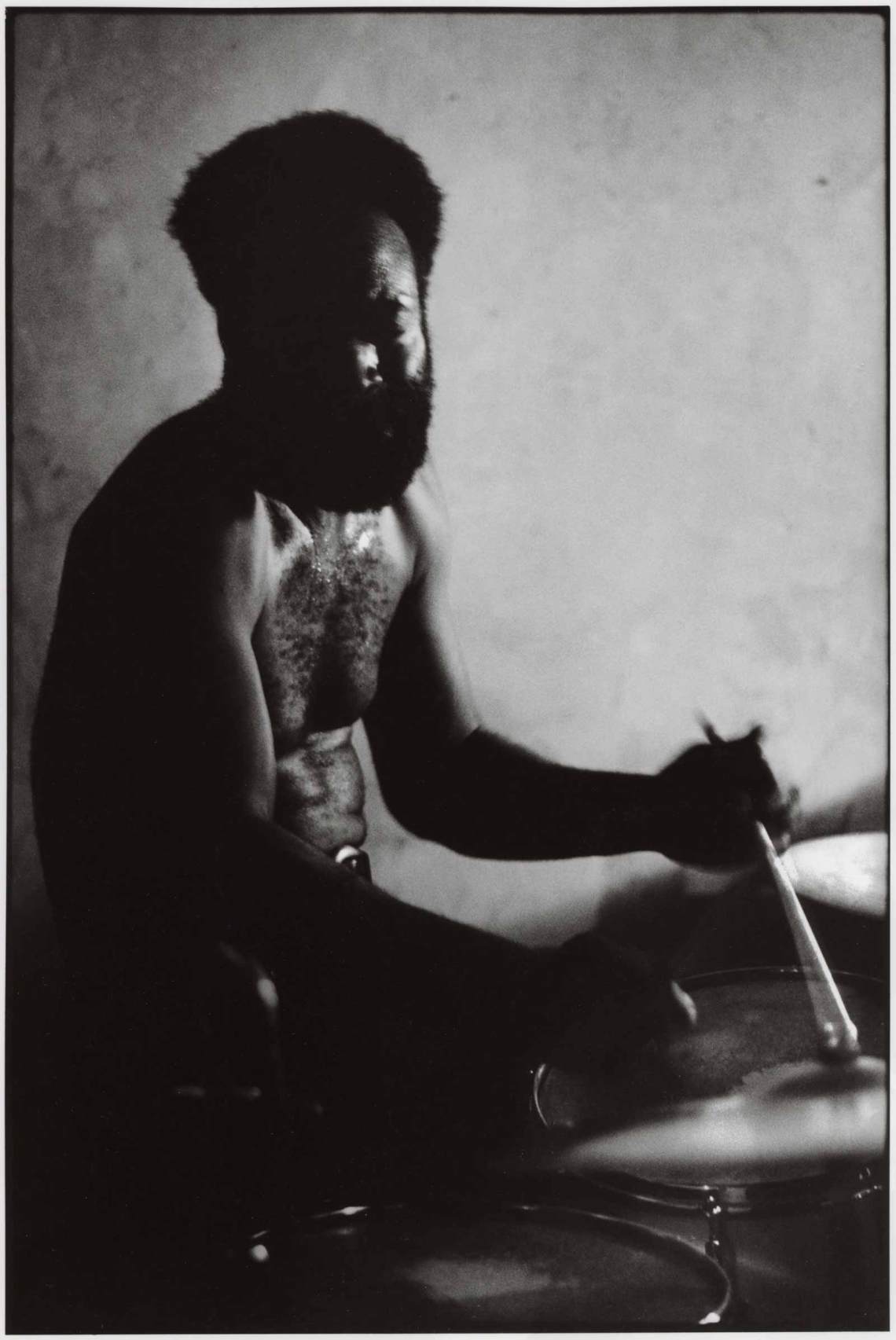

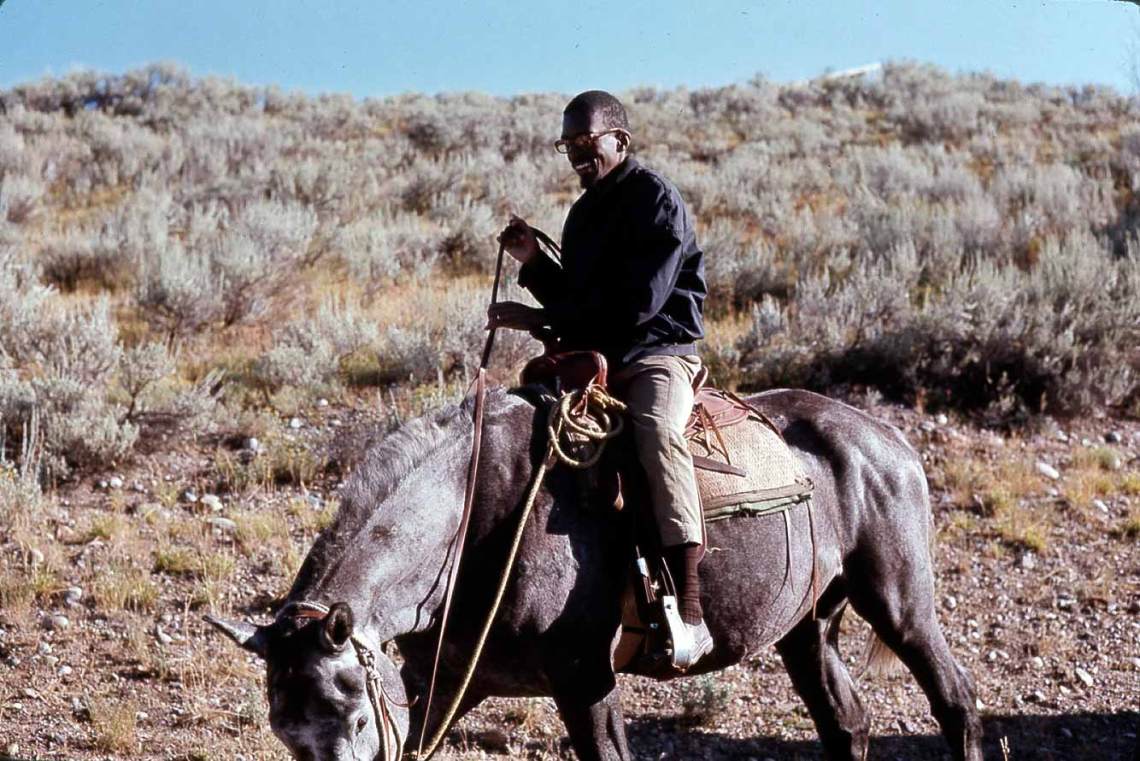

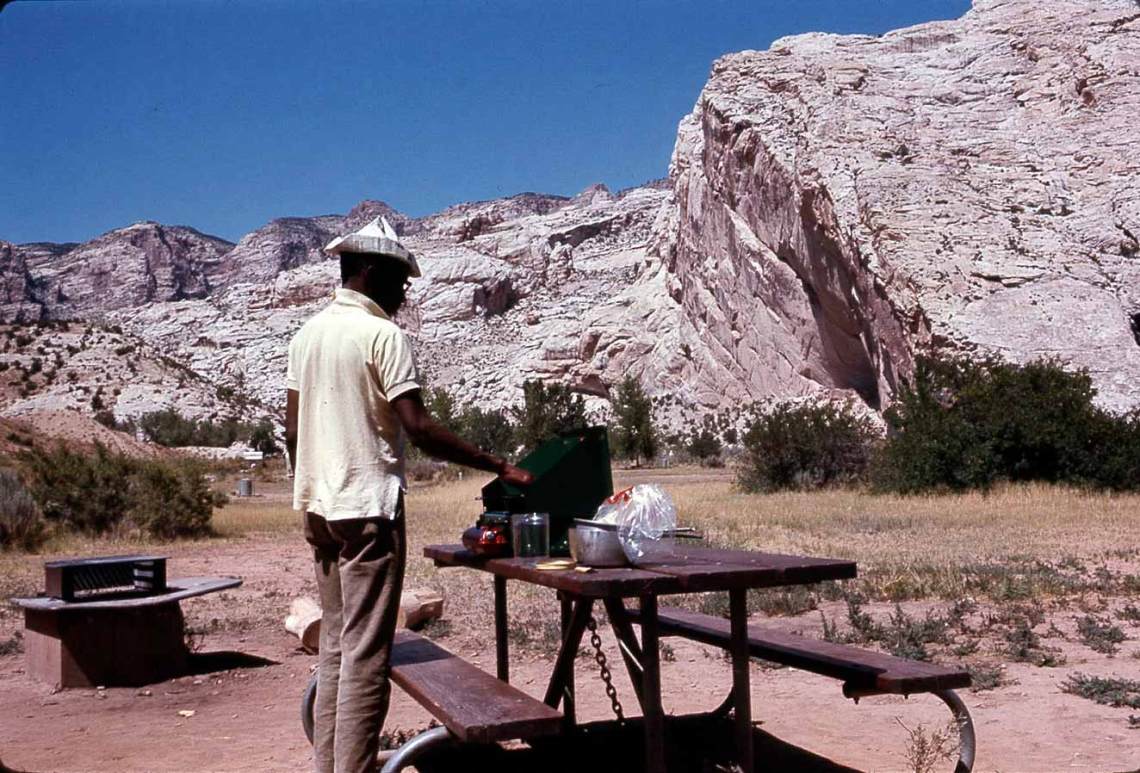

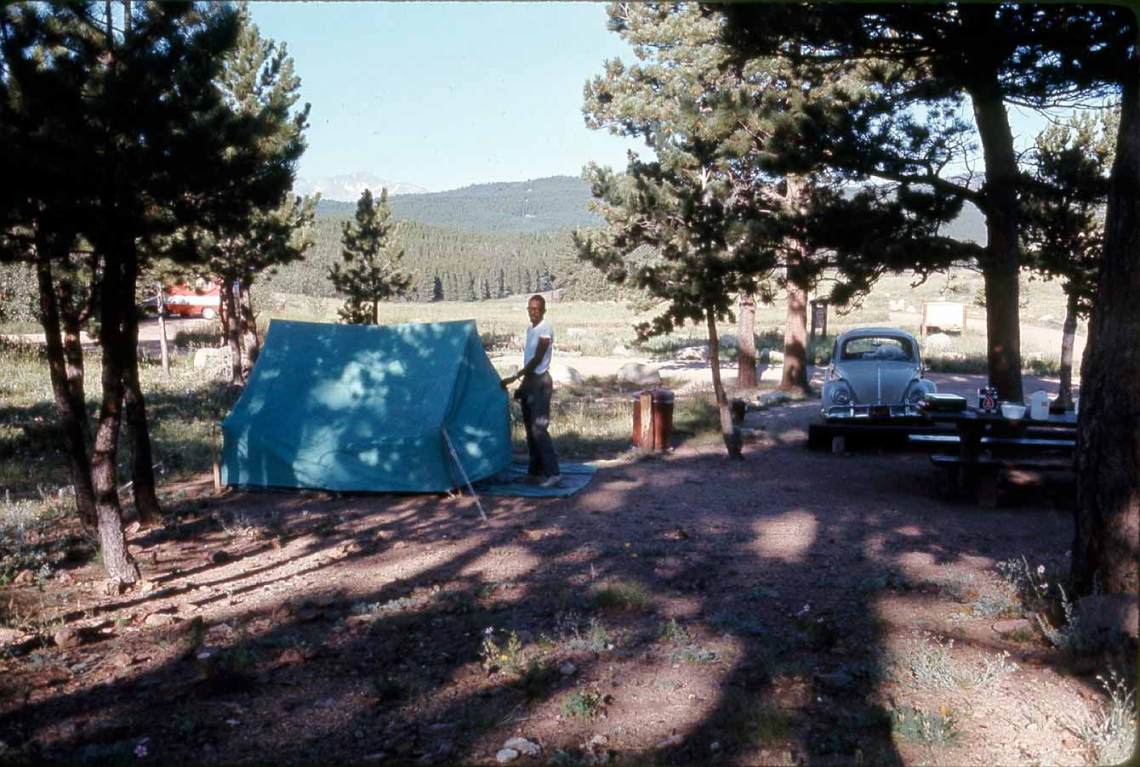

When I was asked to speak at the School of Visual Arts’ Symposium on Arts, Politics, and Narrative, the art critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie told me she wanted me to discuss “the image.” I haven’t been in school for some time, so I wasn’t sure what “the image,” singular, was. We live in a society of images, not of a single image. But I think I see what she means. There are certain images that hold us captive, that freeze the gaze, that inspire or horrify us, to the point where we can’t see that there are other, related images that would permit us to see a more illuminating montage—or, to use a different metaphor, that would open up the music of an artist’s life to a richer and more complex counterpoint. So, rather than present one of the usual images of Eastman in concert, I have chosen to show some photographs that his former lover, Donald W. Burkhart, sent me. They show a relaxed young man on vacation who is neither performing nor posturing, and I find them touching in their ordinariness.

Advertisement

Why is there this need for a mythical Eastman, or a prophetic James Baldwin, or an omniscient Hannah Arendt? I sense that those of us who are horrified by the direction of our politics are seeking heroes, people who not only saw far in advance of their societies, but who also somehow lived in advance of them, as if a fully emancipated life were possible in an unfree society. But in this search for superheroes, rather than people, I fear that we’re not doing them much justice. It would be better, I believe, to record their struggles, not on the stage of history but within history—within the politics of their time, and within their own efforts to define themselves, to find their voices, and to move from thought to expression, which is a struggle for all of us, not just artists. And in this, let us remember that, as Cecil Taylor beautifully put it, people are all, at some level, dark to themselves.

Adapted from a lecture given at the School of Visual Arts, New York City in May 2018.