This essay is the second in an occasional series about feminists and feminist movements left out of conventional history books—not for lack of merit, but because they contravened even the radical notions of their day, or because the establishment dismissed them as crazy, or both. The feminist canon is new and still in the process of formation, and there exists a wealth of forgotten or half-forgotten feminisms worth another look. I have chosen those that offer new (or rather, old) tools for tackling the injustices of our own time.

In this column, I write about the National Welfare Rights Organization, which was active between 1966 and 1975, and some of the men and women who led or influenced it: the black welfare mother Johnnie Tillmon, the black community organizer George Wiley, and the white sociologist Frances Fox Piven and her husband and collaborator, social work professor Richard Cloward. Perceived at the time as an anti-poverty rather than a feminist cause, the welfare rights movement demanded adequate government support for mothers who thought they were already working, just in the home. Long before “intersectionality” was a word, these black women knew that middle-class feminists didn’t speak for them. I draw heavily from a manifesto by Tillmon, “Welfare is a Women’s Issue,” published in 1972, a little-known masterpiece that ought to be read by every feminist in this country.

In a nice, if perhaps pat, coincidence, two of the most consequential women’s groups of the 1960s share an official date of birth: June 30, 1966. One group came into existence quietly, a few blocks from the centers of national power in Washington, D.C., where Betty Friedan was attending a conference on the status of women and feeling disgruntled about the delegates’ failure to pass a resolution opposing sex discrimination. On June 30, Friedan invited some two dozen like-minded conference-goers back to her hotel room. There, she showed them a paper napkin on which she’d scrawled three letters: N O W. The National Organization for Women.

The other group emerged out of a much more visible campaign to raise awareness about the inadequacy of welfare benefits. The effort had begun ten days earlier with the Walk for Decent Welfare, a 155-mile march from Cleveland, Ohio, to Columbus, the state capital. A majority of the hundred or so marchers who trudged the roads were single black women and their children, though far from everyone on welfare at the time was a single black mother or her child. Some two million Americans received Old Age Assistance; a few thousand got Aid to the Blind; half a million people got disability checks; and slightly more than that number of adults without children were on general assistance. But the largest group of beneficiaries, by far, consisted of single mothers and children, more than eight million of them, supported (barely) by what was then called Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). Two thirds of them were white.

Reporters covered the Walk for Decent Welfare with nearly the same level of detail they had accorded the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march. Three days in, the Cleveland Enquirer announced that six marchers had quit the long walk because of “foot trouble,” but another three had taken their place. Others, too, fell by the wayside, and when the remaining thirty-five straggled into Columbus, the Mansfield News-Journal of Ohio recorded what they ate for dinner: meat loaf, mashed potatoes, two vegetables, ice cream, and cake.

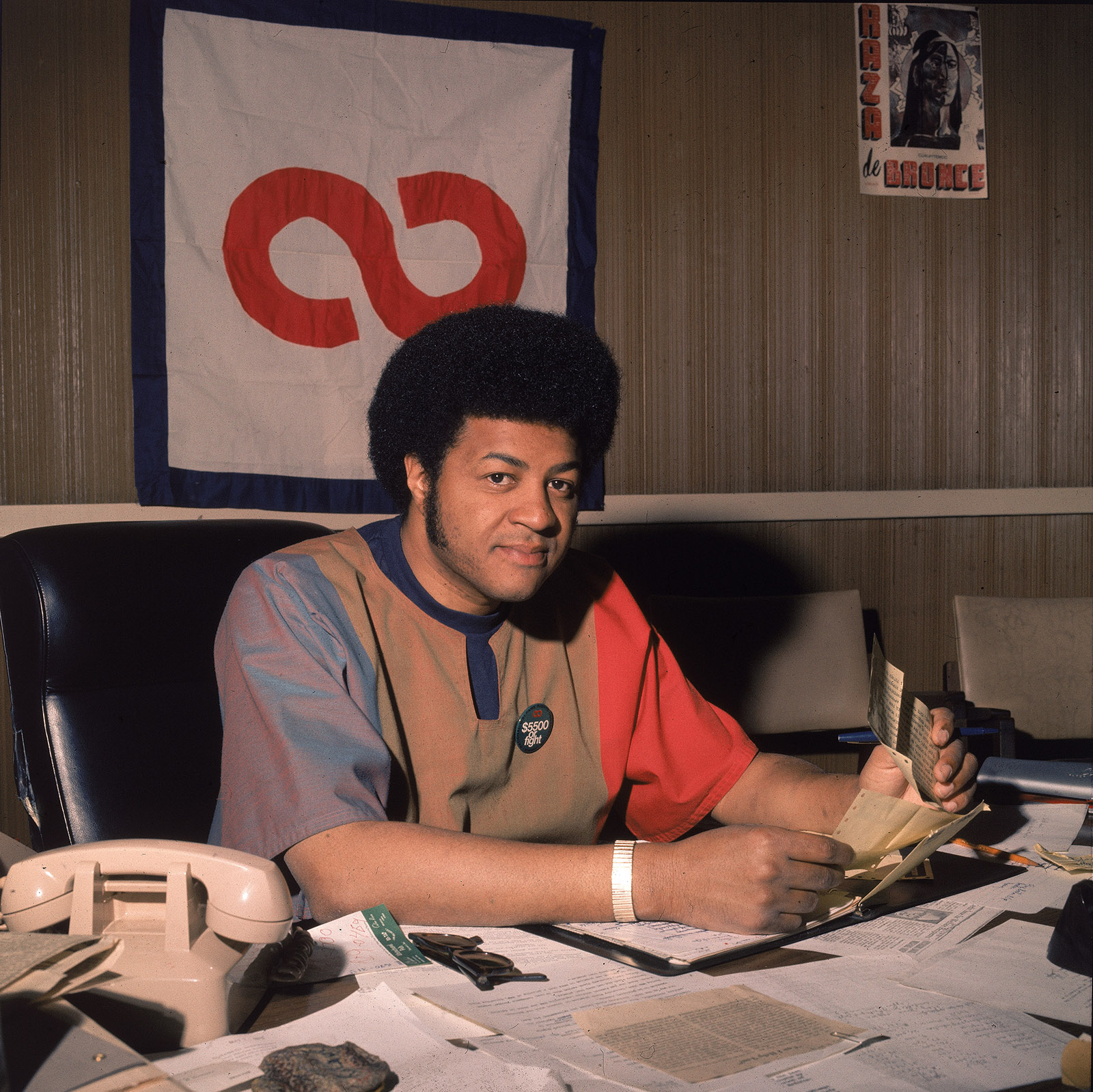

On June 30, the marchers rallied on the steps of the Ohio statehouse. Celebrities such as the comedian and activist Dick Gregory and the head of the Ohio AFL-CIO showed up, along with a small throng of politicians. Meanwhile, welfare-rights demonstrators protested in twenty-five other cities from coast to coast. In Philadelphia, about 150 men, women, and children held a “sleep-out” at a state office building to demand a 30 percent raise in their welfare payments. In Louisville, Kentucky, a hundred people clamored for a federal food stamp program in Jefferson County. A hundred and fifty people gathered in front of New York’s City Hall. The press loved the pageantry. The New York Times and The Washington Post both ran front-page stories, and two of the three big TV networks put the protesters on the air. Several days later, the local anti-poverty groups that had pulled off this media coup came together to form an umbrella group called the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO)—the first national membership organization of poor people in America. Its leader was George Wiley, an African-American chemistry professor turned civil rights activist who had become a “welfare warrior” (in the phrase of one of the NWRO’s leading historians, Barnard professor Premilla Nadasen) leading an army of fired-up black mothers.

Advertisement

Half a century later, the National Organization for Women is the largest and most established feminist group in the nation, while the National Welfare Rights Organization has all but vanished from public memory. Everyone knows who Betty Friedan is. Few besides researchers and historians of welfare have likely heard of the NWRO or its leaders. Yet during the nine short years of its existence, it improved the lives of a large cohort of American women and children who, arguably, were in greater need than any other. It won millions of dollars for women unfairly kept off the welfare rolls; secured grants for clothing, furniture, and children’s medical services; helped to create the food voucher program known as WIC (for Women, Infants, and Children); and, in a remarkable feat, convinced department stores such as Sears to extend credit to AFDC recipients for the big-ticket household items that middle-class consumers took for granted. Together with civil rights lawyers, the NWRO succeeded in persuading judges to strike down such standard features of life on welfare as the “man-in-the-house” rule. This shockingly demeaning provision allowed investigators to raid mothers’ homes at any time of day or night to hunt for the men who, it was felt, should support needy families (instead of the government). A caseworker who found a man on the premises, or even saw a man’s clothes in a washing machine, could cut off a woman’s benefits.

The NWRO’s obscurity should perhaps not come as a surprise. Welfare as a cause has dropped off the domestic political agenda over the last fifty years. It’s no longer even popular on the progressive left. You don’t hear Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren talking about welfare; they denounce inequality, which is not the same thing. Inequality is the gap between the rich and the poor—and if you’re a politician, you say, “the working poor.” The form of poor relief that earns the most praise, the Earned Income Tax Credit, goes to low-income parents with jobs—in other words, “the deserving poor.” Welfare recipients, on the other hand, are considered toxic, and are politically isolated. This is a tragic circumstance, given that welfare support as the NWRO knew it has vanished. Aid to single mothers today is a fraction of what it once was. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, just 23 percent of the poorest families got cash assistance in 2016, down from 68 percent in 1996.

“Welfare’s virtual extinction has gone all but unnoticed by the American public and the press,” write Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer in $2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America. In that 2015 book, Edin and Shaefer relate their startling discovery that the number of households living in extreme poverty (which they define as living on an income of $2 a day per family member) had skyrocketed since the Clinton administration enacted its welfare reforms in 1995. In 2018, Edin and Shaefer published a paper in which they observed that between 1995 and 2012, the number of children in $2-a-day households tripled, from 415,000 (0.6 percent of all children) to 1.2 million (1.6 percent). Children of single mothers experienced the most concentrated surge in deep poverty during that period—an increase of 748 percent in their numbers. “If, before, all the children in single-mother families experiencing extreme poverty could fit into a single football stadium,” they write, “as of 2012 we had a population living in annual extreme poverty that was as large as the total number of children in a large city like, say, Chicago.”

Another explanation for the NWRO’s nonappearance in histories of feminism is that mainstream feminists never quite knew what to do with the welfare rights movement. It scrambled all the known categories. Here was a group of mothers who, rather than wanting equal work and equal pay, demanded that the government support them while they stayed home and raised their kids. That didn’t sound like the kind of women’s liberation NOW’s supporters were fighting for. The NWRO’s organizational structure was also confusing. It was run by a man, Wiley, with a mostly male, largely white staff that was made up of professional community organizers in the tradition of Saul Alinsky. As for the mothers in the rank and file, including the few elected to leadership positions, well, they just didn’t look like feminists. For one thing, they were mostly “middle-aged” and “fat”—those were the words of the movement’s most effective spokeswoman, Johnnie Tillmon, the group’s first chairwoman and, toward the end of its run, its director. In her 1972 essay, “Welfare Is a Women’s Issue,” Tillmon wrote:

I’m a woman. I’m a black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. And I’m on welfare. In this country, if you’re any one of those things you count less as a human being. If you’re all those things, you don’t count at all.

Another thing that could keep a woman from counting was wearing the wrong clothes. The mothers, including Tillmon, showed up for protests and political meetings in church outfits. Wiley’s young aides took to calling them “the ladies,” and complained that they should be highlighting their poverty, not their hats. The “ladies,” however, had no intention of diminishing their dignity with unkempt hair or miniskirts.

Advertisement

The National Welfare Rights Organization didn’t disconcert only feminists; it unnerved white liberals as a class. The “ladies” may have looked like bake-sale volunteers, but they were radical and acted it. Trained by Wiley and his staff in the art of direct action, they had no qualms about being impolite. They occupied welfare offices and refused to leave. On occasion, they tore phones off walls and pulled case-files out of filing cabinets. For a time, the militancy worked. A 1968 article in The New York Times reported that “bands of organized clients… have jammed the centers, sometimes camping out in them overnight, broken down administrative procedure, playing havoc with mountains of paperwork, and have been increasingly successful.” But the incivility scared away allies, too, and would later contribute to the movement’s decline.

Yet the reasons the women of the NWRO faded from view are the very reasons to resurrect their legacy now. These activists were black and broke and older, and their experiences and desires had few points of intersection with those of the young, white, well-educated women who strode confidently into the spotlight and defined feminism then—and define it even still now. Race and poverty made the welfare rights movement’s critique of work and motherhood relevant today. We who strive and fail to master the so-called work-life divide; who watch as the gig economy and artificial intelligence deprive us of jobs, steady income, and health care; who live in the industrialized nation with the worst caregiver policies in the world; who watch the rich get richer and the poor get poorer—we need to hear what the NWRO, and Tillmon in particular, had to say.

Welfare wasn’t supposed to go to single black mothers. Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), an early version of Aid to Families with Dependent Children, passed as part of the Social Security Act of 1935, was meant for widows and deserted wives who had lost their husbands’ wages through no fault of their own. No one expected these women to work. It was assumed they’d stay home and take care of their children. But black women, then mostly living in the South, were expected to work, usually as maids and field hands—and the bill specifically excluded domestic and farm workers, including women. That was the price for the support of Southern legislators, who were essential to the bill’s passage. Black women had been a source of such labor since slavery, and emancipation hadn’t changed things much. If they stopped working, as Senator Russell Long (Democrat of Louisiana) once infamously asked, then who would iron his shirts? Long was expressing a widely held Southern view. During the 1940s and 1950s, Louisiana and other Southern states stopped issuing welfare checks during cotton-picking season.

In 1939, tweaks to Social Security made it possible for widows and their children to get survivors’ benefits, and they left the rolls of the ADC. It became primarily a program for divorced or unmarried mothers and their children. After World War II, the number of black welfare clients doubled and tripled. A backlash gained momentum and an old stereotype took a new form. The welfare recipient was transmogrified into a shiftless, promiscuous cheat. Never mind that more white than black women got government assistance: whites saw welfare mothers as black. In state after state, nasty rhetoric gave rise to nasty rules: the “man-in-the-house” diktat; laws requiring that households be “suitable,” a code word meaning that their children weren’t born out of wedlock; and residence requirements that denied welfare to anyone who had recently moved from out of the state.

It was the disrespect that galled welfare recipients the most. “The demand for respect is foremost on the list of every welfare-client organization in the country,” reported an organizer in 1965. Caseworkers had total power and could use it capriciously, cutting benefits, refusing requests for emergency grants, and terminating aid without notification or the chance to appeal. Even asking for aid invited humiliation. “The moment they walk in the door of a Welfare Center to apply for help, people are stigmatized,” observed Jennette Washington, an NWRO member. “They are lined up like cattle begging for a meal.”

Johnnie Tillmon had firsthand experience of such degradation. A feisty, self-reliant soul born to a sharecropper family in rural Arkansas, she had worked since she was seven. Her first job was in the cotton fields—not, she later told an oral historian, because her parents needed the wages, but because she was wild and they wanted to keep an eye on her. After leaving a bad marriage—her husband had been “running around”—she worked mostly in laundries. Wherever she went, she got involved in politics. After she moved to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, she became a union shop steward, registered voters during local races, and joined her housing project’s community association.

Tillmon had six children to support, but she’d heard the stories about welfare, and didn’t want to sign up. One day, though, she was hospitalized for tonsillitis. The head of the neighborhood association visited and told her that her teenage daughter had been skipping school, and that she ought to get on welfare so she could spend more time with her kids. In fact, he had already called downtown to start the paperwork for her. Unsurprisingly, Tillmon found her new life intolerable. Caseworkers inventoried her refrigerator, gave her a budget to follow, and asked prying questions about the men in her life. Within eight months, she had founded one of the first welfare rights groups in the country.

As Tillmon tells the story, what radicalized her was a particularly humiliating incident involving a sprinkler. “In the housing project in those days, if you didn’t keep your grass watered and green, the men used to come and turn your water hose on and charge you $3.25 for it,” Tillmon told the oral historian. So Mrs. Jackson, Tillmon’s neighbor, kept her sprinkler going on weekends. A church nearby had an overflow parking lot next to Mrs. Jackson’s apartment. One Sunday, a churchgoer parked her perfectly maintained 1959 Valet Ford in the lot. Mrs. Jackson’s sprinkler “went around and around, the water went across the hood of this car. Lady come out of church around 1:30, quarter to 2… walked out of the church with her hat on all nice and just had a fit.” The woman began screaming about the kind of people who lived in housing projects, “all of us on welfare, sitting down lazy and so on and didn’t have any money,” said Tillmon, “and my eyes just went like that.”

Being yelled at by a church lady was the final affront. Tillmon went to her friend at the community association and said, “We oughta do something.” What she did was sly but effective. She sent notes to every woman in the housing project on welfare asking them that they come to the office to discuss their lease and benefits. Three hundred worried women showed up. First, Tillmon reassured them; then, she organized them. She went to another housing project, and another. The women she gathered together called themselves Aid to Needy Children (ANC) Mothers Anonymous, and by August 1963, they had opened an office staffed by welfare recipients who helped others fight back against the bureaucracy, hold on to their checks, get the special grants, and give their children the food, clothes, and shelter they needed.

You might say that the welfare rights movement was both behind the times and ahead of them. Even before the Marxist-oriented—and equally misunderstood—Wages for Housework group came along in the late 1960s and 1970s to defend women’s work as an unacknowledged form of proletarian labor, the women of the NWRO understood that their unpaid daily grind had value—social as well as economic—and deserved recognition and compensation. “The ladies of NWRO are the front-line troops of women’s freedom,” wrote Tillmon. “Both because we have so few illusions and because our issues are so important to all women—the right to a living wage for women’s work, the right to life itself.”

Defending women’s work was not on NOW’s agenda, however; at least not in the 1960s. Its bible, Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, spoke to middle-class wives who’d married for lack of other options and felt they were wasting their education and talents on children and chores. They wanted out of the house. They wanted professional fulfillment and equal pay.

Between the NOW-style feminists and the welfare rights movement lay a class divide and a culture gap. “We thought white women were crazy to want to give up their cushiony Miss Cleaver life,” said Catherine Jermany of the Los Angeles County Welfare Rights Organization. “We thought that was a good life.” NOW, on the other hand, drafted a Bill of Rights in 1968 that demanded “that poor women be given the same access to opportunities as men, without prejudice based on their status as mothers.” It probably didn’t occur to the drafters that the workplace may have held less allure for black mothers than for white ones, since neither black men nor black women had much access to opportunity, whatever their parental status.

NWRO members sometimes went to NOW meetings, but they rarely felt welcome. Some NOW members had called the NWRO’s insistence on the choice to work or stay home a “hollow choice”; welfare activists were said to perpetuate sexist stereotypes. The NWRO didn’t necessarily like the feminists who visited them either. They weren’t pleased when Gloria Steinem spoke at one of their meetings in 1971 and trashed men—at least, that’s how they interpreted her remarks. The welfare mothers didn’t see the male-female divide the way younger feminists did. They didn’t have a beef with individual men or with marriage as an institution—many of them would have been glad to have husbands. What they felt trapped in was a dysfunctional relationship with an abusive state.

“Welfare is like a super-sexist marriage,” wrote Tillmon, in the most famous passage of her essay. “You trade in a man for the man. But you can’t divorce him if he treats you bad. He can divorce you, of course, cut you off anytime he wants. But in that case, he keeps the kids, not you. The man runs everything.” In the 1970s, the man was understood to be cops, prison guards, housing authorities, the entire apparatus of white control over black bodies. “The man, the welfare system, controls your money,” Tillmon continued. “He tells you what to buy, what not to buy, where to buy it, and how much things cost. If things—rent, for instance—really cost more than he says they do, it’s just too bad for you. He’s always right.”

Reproductive freedom was another area in which the two camps agreed superficially but misunderstood each other in fundamental ways. Mainstream feminists thought it meant access to birth control and abortion. Minority women, well aware that in the not-so-distant past, eugenicists had launched campaigns to limit their fertility, understood it to mean being able to have as many children as they wanted, when they wanted them. Even then, these women had to worry about being sterilized in order to qualify for federal benefits. As usual, Tillmon put it forcefully:

In ordinary marriage, sex is supposed to be for your husband. On AFDC, you’re not supposed to have any sex at all. You give up control of your own body. It’s a condition of aid. You may even have to agree to get your tubes tied so you can never have more children just to avoid being cut off welfare.

Tillmon’s final word on reproduction was this: “Nobody realizes more than poor women that all women should have the right to control their own reproduction.” If you’d taken that sentence and put it on a placard and waved it at a protest back then, white women and black women would have thought it meant very different things.

Over time, the National Welfare Rights Organization began to focus less on welfare rights and more on a guaranteed minimum income. Minimum income was meant to be a lifeline for all, stripped of any eligibility requirement other than straight-up economic need. This particular emphasis owed much to two Columbia University professors, Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, who in the early 1960s developed some unusual theories about fighting poverty. They saw that people on welfare weren’t getting as much money as they were owed by law, and that millions of others weren’t getting any part of what they were due: “For every person on the rolls, there was another who was eligible.” If the poor could unite and form a mass movement and demand all the cash assistance the law said they should have, Piven and Cloward argued, that “would surely make a dent in the hunger, malnutrition, and poverty problem in the United States.” But Piven and Cloward didn’t stop there. They wanted to get rid of welfare altogether. Their thinking went like this: if all the people who were eligible got what they were owed, they’d break the banks of city and state governments, and the welfare bureaucracy would collapse. In the face of such a crisis, the federal government would have to intervene. The most logical intervention would be a guaranteed income, which, in Piven and Cloward’s view, would be the fairest redistribution of wealth to the poor.

As strategies go, it was risky—what if breaking the bank led to less welfare, not more?—but Cloward found someone willing to try it. George Wiley had taken a leave from a professorship at Syracuse University in the early 1960s to join the Congress of Racial Equality, which had organized the Freedom Rides; he rose in CORE’s ranks, then lost a battle to become its leader and quit. Wiley liked the idea of mobilizing the poor and agreed with Piven and Cloward that a guaranteed minimum income was a good idea. Wiley never returned to academia. Instead, he visited the welfare rights groups that, like Tillmon’s, were popping up around the country in order to learn what they were thinking. In the spring of 1966, he helped the Ohio group orchestrate the Walk for Decent Welfare and concurrent protests. He convened a “national welfare rights meeting” in Chicago a few months later, in August 1966.

Tillmon came to that meeting and found it electrifying. “Most of us had never been anywhere before, never met other people outside our own cities, never had an opportunity to talk about ourselves, our organizations, our communities,” she said. “People felt something they never felt before. They knew they weren’t alone in the situation.” One of the most empowering ideas was that welfare wasn’t charity but a right, because everyone deserved a decent standard of living. Tillmon explained with her usual pithiness: “The truth is a job doesn’t necessarily mean an adequate income. There are some ten million jobs that now pay less than the minimum wage, and if you’re a woman, you’ve got the best chance of getting one.”

A guaranteed income for the poor wasn’t as novel as it sounded; nor was the idea the sole property of the radical left. The American revolutionary Thomas Paine had declared that nations should give every twenty-one-year-old a lump sum on the grounds that those who inherit land have an unfair advantage over those who don’t. The libertarian thinker Friedrich Hayek supported “a sort of floor below which nobody need fall.” Another fierce defender of free markets, the Chicago School economist Milton Friedman, called for a negative income tax according to which, if you reported less than a certain amount, the Internal Revenue Service would pay you.

Between 1965 and 1970, the number of families on welfare more than doubled. So, too, did total AFDC payments, from $6.3 billion to $14 billion. Much of this growth reflected rising unemployment. But the welfare rights movement was having an effect, too. Administrators attested to the fact that recipients acted as if they were owed their benefits, rather than humbly accepting their alms.

The National Welfare Rights Organization’s successes impressed the leaders of the civil rights movement. Andrew Young, a senior aide to Martin Luther King Jr., once gave the welfare movement credit for helping to turn King and the Southern Christian Leadership Council toward economic issues in the second half of the 1960s. In 1967, at a speech at Stanford University, King declared, “It seems to me that the Civil Rights movement must now begin to organize for the guaranteed annual income.” When King was planning the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, he sought the NWRO’s endorsement. The encounter gave the organization’s women a chance to exact some revenge; they had often asked to meet him and had been rebuffed. So the NWRO made King come to a meeting to ask for its endorsement in person. When he showed up, the women bombarded him with technical questions about pending welfare legislation. King hemmed and hawed until Tillmon said, “You know, Dr. King, if you don’t know, you should say you don’t know.” King looked her straight in the eye and said, “Mrs. Tillmon, we don’t know about welfare and we have come to learn.” Watching King defer to Tillmon thrilled the women of the NWRO; the men of the civil rights movement were not known for listening to women.

The push for a guaranteed minimum income yielded results in 1969, when the NWRO was at the peak of its influence. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the Harvard professor (and later, Democratic senator) who had become President Richard Nixon’s urban policy guru, held a press conference at the White House to announce the Family Assistance Plan (FAP). Nixon thought that calling it a guaranteed minimum income plan would alienate conservatives and Moynihan didn’t use the term, but that’s what it was. The measure was designed to replace the AFDC. Had it passed, the FAP would have been, as Moynihan later wrote, “the most far-reaching new domestic legislation since the New Deal.” All families below the poverty line would get Tom Paine’s lump sum. It wouldn’t be taken away even if someone in the family was already working. No one would come sniffing around to see whether there was one parent in the household or two. Since the subsidy would come from the federal government, it wouldn’t vary from state to state, the way welfare did. (Welfare checks in the South tended to be a fraction of those in the North.) A week after the announcement, Gallup polls found that two thirds of the nation, Republicans as well as Democrats, supported the FAP.

The Family Assistance Plan seems unimaginably progressive by today’s standards, but it wasn’t received that way at the time. The NWRO thought the stipends were stingy: $1,600 for a family of four (or with food stamps, $2,464; about $14,000 in today’s values). The “ladies” declared that $2,464 wouldn’t pay for a nutritious diet or any of the other special needs they’d fought for, such as clothing, furniture, and so on. They drafted a counterproposal and had it introduced in the Senate by Eugene McCarthy (Democrat of Minnesota), the former presidential candidate and liberal champion. His legislation called for a minimum income of $5,500 for a family of four; the NWRO later upped that amount to $6,500.

The NWRO women had another objection to the FAP, however—one not shared by Wiley. The Moynihan proposal had a work requirement: all able-bodied adults and parents whose children had entered school would have had to register for work or training or lose their benefits, although their children would keep theirs. President Nixon called this “workfare,” and he was the first politician to use the term that Clintonian welfare reform turned into common parlance two decades later. Moynihan later argued that some incentive to work had to be included “to protect the program from political attack from the right,” and to make sure that the program “decreased dependency” and “increased the number of families that were essentially self-sufficient.” Wiley agreed with Moynihan that a guaranteed-income program would indeed have to exhibit “a certain degree of reverence for the Protestant ethic” in order to be palatable to the American public, and that dependency was a thing to guard against. The “ladies” were having none of it. Their position was that if mothers were dependent, that’s because they weren’t being supported in the work they were already doing. They took workfare as an abridgment of their rights as mothers. As one of their leaders, Beulah Sanders, wrote to the House Ways and Means Committee:

Surely the mother is in the best position to know what effect her taking a particular job would have on her young school child, but now we are told that for welfare mothers the choice will be made for them, work for the mother, government centers for the children, the government decides.

The NWRO lobbied individual politicians in an effort to raise the stipend, but when that didn’t seem to work, the organization escalated its tactics. Wiley started characterizing the bill as a racist attack on the poor. The NWRO came up with a slogan, “Zap FAP,” and called for poor people to rise up and protest against the bill. Members of the NWRO camped out for an entire day in the office of Robert Finch, the secretary of the Department of Housing, Education, and Welfare, until they were evicted and arrested. The Washington Post ran a photograph of Wiley smiling and leaning back expansively in Finch’s chair, his feet up on the desk. Then the mothers staged a three-hour “wait-in” at the Senate Finance Committee’s hearing room to demand the right to testify. The committee’s chairman—the segregationist Long, as it turns out—sniped: “If they can find time to march in the street, picket, and sit all day in committee hearing rooms, they can find time to do some useful work.” The Post’s photograph that day featured Tillmon pointing an accusatory finger, her face distorted by anger. The press was turning against the NWRO.

The FAP got through the House of Representatives, but died in the Senate Finance Committee. Moynihan blamed the NWRO, accusing it of having become an urban welfare elite that was too afraid of losing its cushy benefits to understand that his plan would raise the standard of living for “the working poor in Maine, Puerto Ricans in the Caribbean, Navajos in New Mexico, even blacks in Mississippi.” Moreover, by invoking race in their criticism of his bill, Moynihan said that the NWRO had squandered “a significant social opportunity,” because, he added bitterly, “Whites could not say this, but blacks could have. But blacks, too, were traumatized. To contradict the NWRO was both to break ranks and to risk a fearsome fury.”

It is hard not to hear the sexism in the phrase “fearsome fury,” or Moynihan’s rage toward blacks who refused to express the proper gratitude. But the death of the FAP marked the beginning of the NWRO’s decline. By 1971, the organization had half the membership it had had two years earlier. It was losing as many battles as it was winning, and even when it won, it lost by inciting further opposition. Wiley tried to form alliances with other poor people’s groups and the anti-war movement; while they welcomed his help, they didn’t return the favor by doing much for him. Besides, the other NWRO leaders felt that these partnerships diluted their message. In 1972, they pushed Wiley out as executive director and replaced him with Tillmon. She lacked his fundraising skills, however, and by 1975, the organization could no longer pay the rent or the telephone bills for its basement office in Washington, and shut itself down.

The demise of the NWRO did not signal the end of the welfare rights movement. Local groups kept advocating for recipients for decades, but they had lost their most visible representative. In 1973, Wiley and some former NWRO associates started a populist, grassroots organization meant to appeal to all low-income and middle-income Americans, not just blacks and welfare recipients, which they called the Movement for Economic Justice. Its causes would be better jobs, tax reform, national health insurance, decent housing, and other still-pressing objectives. Later that year, however, Wiley died during a storm on the Chesapeake Bay, falling over the side of an old eighteen-foot wooden cruiser he’d bought and was planning to fix up for his children. The Movement for Economic Justice limped along for three more years, until it, too, closed, in 1976. Tillmon, meanwhile, moved back to California and settled not far from her old housing project in Watts with her new husband, Harvey Blackston, a blues harmonica player of some renown. She worked with a local welfare rights group and became an adviser to then-Governor Jerry Brown, and later to the Republican Governor George Deukmejian. She died, aged sixty-nine, of diabetes in 1995.

By then, much of what she had fought for had died, too. It is possible to trace a line from the coded sexism and racism of Moynihan’s complaints about the National Welfare Rights Organization through Ronald Reagan’s open attacks on welfare mothers (“lazy parasites,” “pigs at the trough”) to Clinton’s 1996 welfare reform, Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF), which replaced the AFDC. Besides imposing “workfare” and giving recipients only a certain number of years of welfare (the number varies from state to state), TANF distributes welfare funds to states in the form of block grants. States can do what they want with that money, and what many of them have done is siphon it off for other programs; they then deal with the shortfall by making eligibility requirements ever more stringent and the process of applying for welfare ever more onerous. When Edin and Shaefer went from city to city to research their book $2 a Day, they found that many of the poor mothers whom they encountered hadn’t even heard of TANF, and didn’t know they were entitled to its benefits. In their telling, one potential recipient finally yielded to her friends’ insistence that she should apply: after waiting all day standing in line, she was told to go home and apply online—and then told she’d still have to come back for an appointment and wait in line again. Food stamps (SNAP) and the children’s health insurance program (CHIP) are better known, but the Trump administration is now trying to dismantle those programs, too.

But if welfare has all but died, the idea of a basic income has enjoyed a resurrection, bringing us full circle back to Piven, Cloward, and the NWRO. The universal basic income (UBI), like the guaranteed minimum income before it, finds advocates on both the left and the right. Among the UBI’s most vocal supporters are Silicon Valley executives who argue that virtually everyone will need a guaranteed income as they’re displaced by robots with advanced artificial intelligence and the ability to perform even managerial jobs. There are as many versions of the UBI as there are people clamoring for it. Libertarians such as the Cato Institute and Charles Murray see it as a way to shrink government, since a central bureaucracy would no longer have to administer so many programs; Murray’s version of UBI would wipe out all other forms of assistance, including Medicare and Social Security. Andy Stern, the former union leader, agrees with those who say that jobs aren’t coming back, but his UBI would hold onto health insurance and Social Security. Plenty of respected economists scoff at the whole idea, which they estimate would cost as much as $3 trillion a year in the US. Its advocates see it as a necessary and inevitable redistribution of the wealth currently hoarded by the exorbitantly rich, to be funded by wealth taxes, financial-transaction taxes, and military spending cuts.

As driverless cars and trucks threaten to make obsolete the largest single occupation in the United States, it is becoming clear that the idea of a UBI is not going away. Finland is still pressing ahead with a pilot program. Canada is conducting its own tests. The bankrupt city of Stockton, California, will be handing out $500 a month to about a hundred low-income families in the fall, no strings attached. There’s a passionate debate about a UBI in Scotland. It seems an apt moment to recall the NWRO and heed its objections. Any floor under the needy must be generous enough to let people live with dignity, and it should be attentive to the particular needs of caregivers (some versions of UBI would withhold it from children, a policy that would punish stay-at-home parents). And today’s women’s rights advocates should embrace the policy, rather than leave it to the handful of economists who understand that it’s a feminist cause. As the women of the NWRO knew through hard experience, society owes a big debt to mothers for the work they do free of charge to rear the next generation and enrich the world.