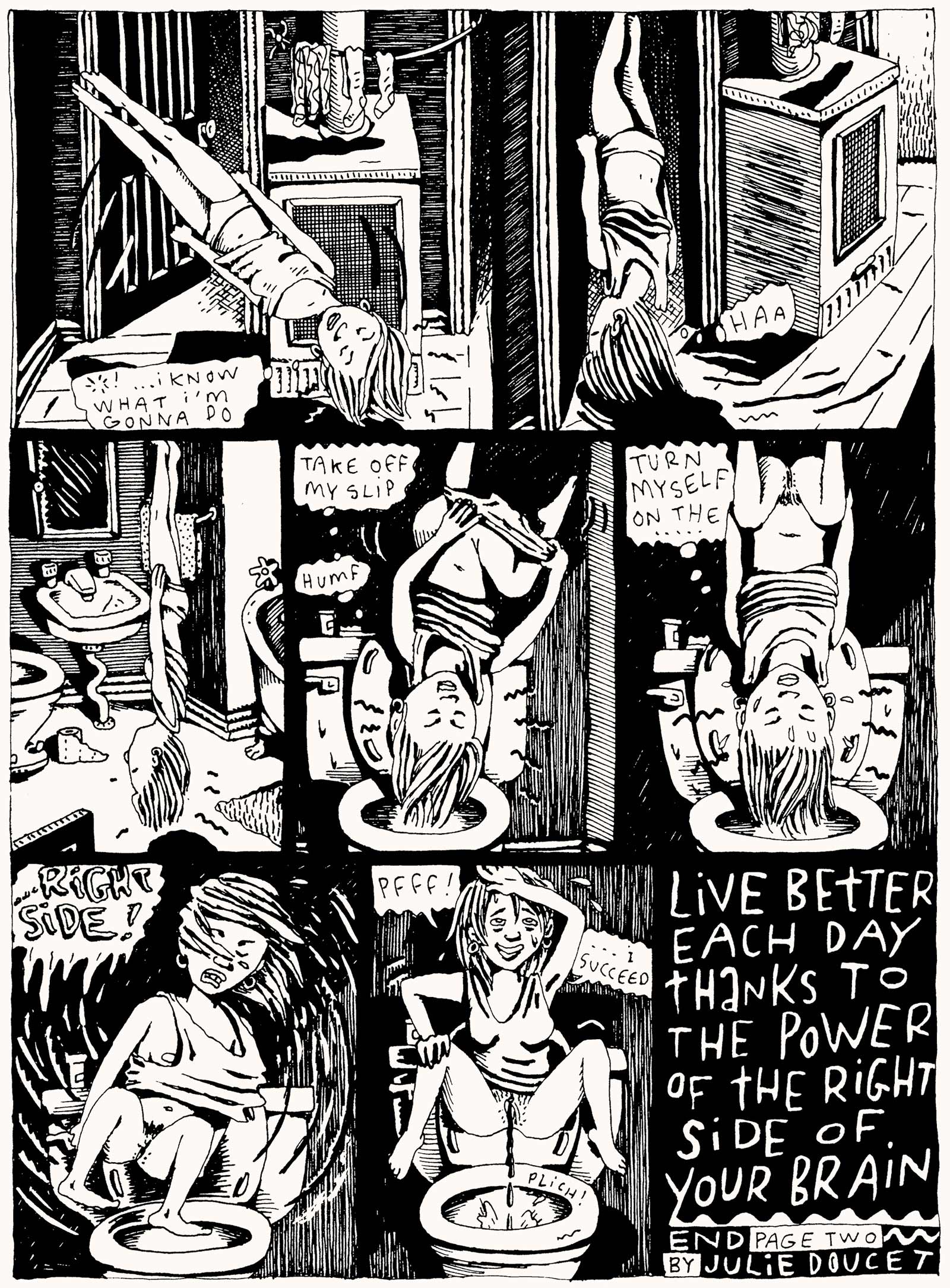

The Canadian artist Julie Doucet began self-publishing the zine Dirty Plotte in 1988, when she was twenty-two. She had been drawing comics since high school, but this was her first sustained project. Working at a feverish pace, she produced fourteen issues of Dirty Plotte in eighteen months before it was picked up by Chris Oliveros as the debut book from his new publishing outfit in Montreal called Drawn & Quarterly, which went on to publish twelve issues by Doucet from 1990 to 1998, incorporating material from the original run with new work. Louche, mordant, funny, and surreal, Dirty Plotte comprises a mix of short and long comics—wordless and with dialogue, narrative and plotless, autobiographical and fictional (and everything between)—in which there are no rules.

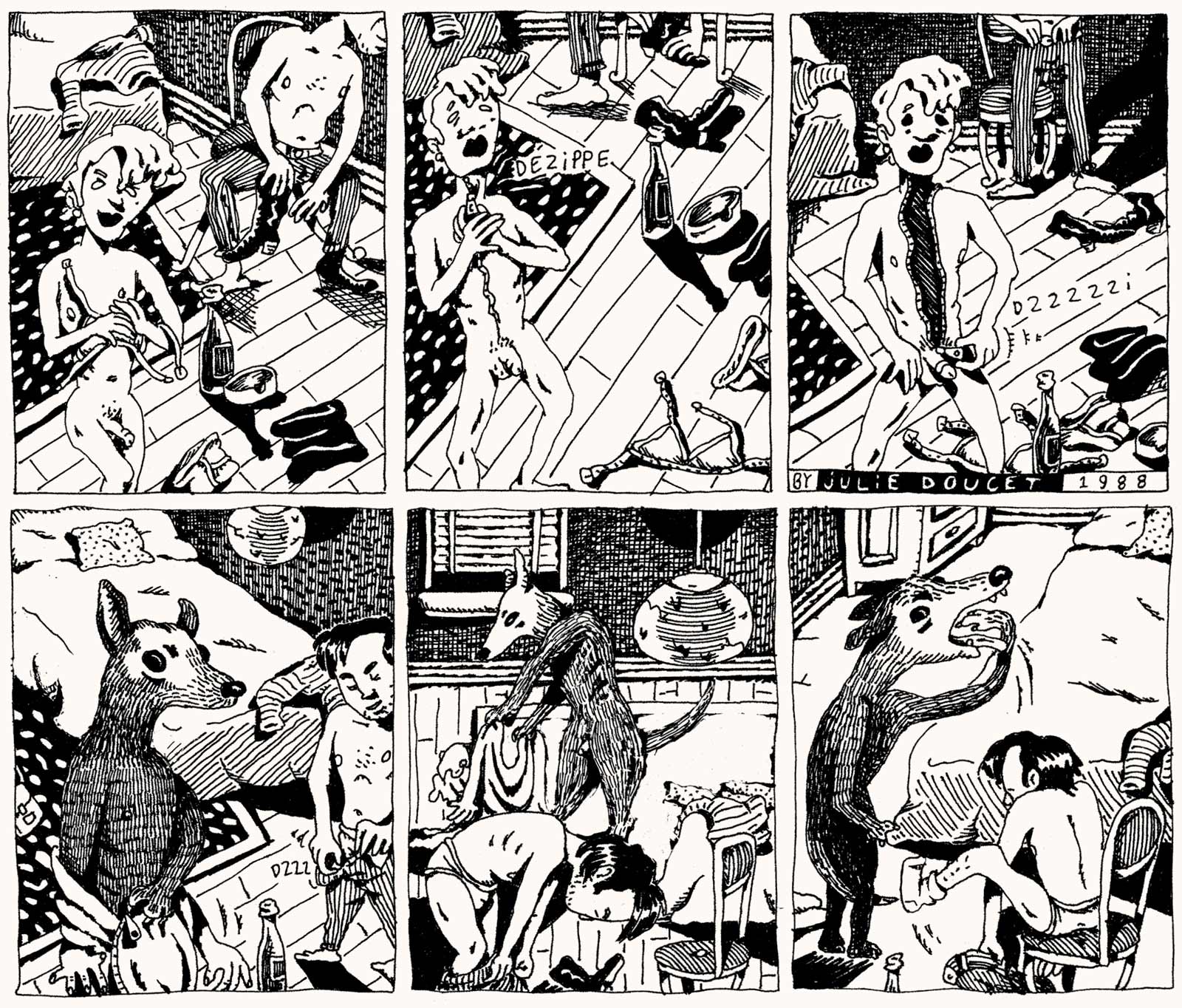

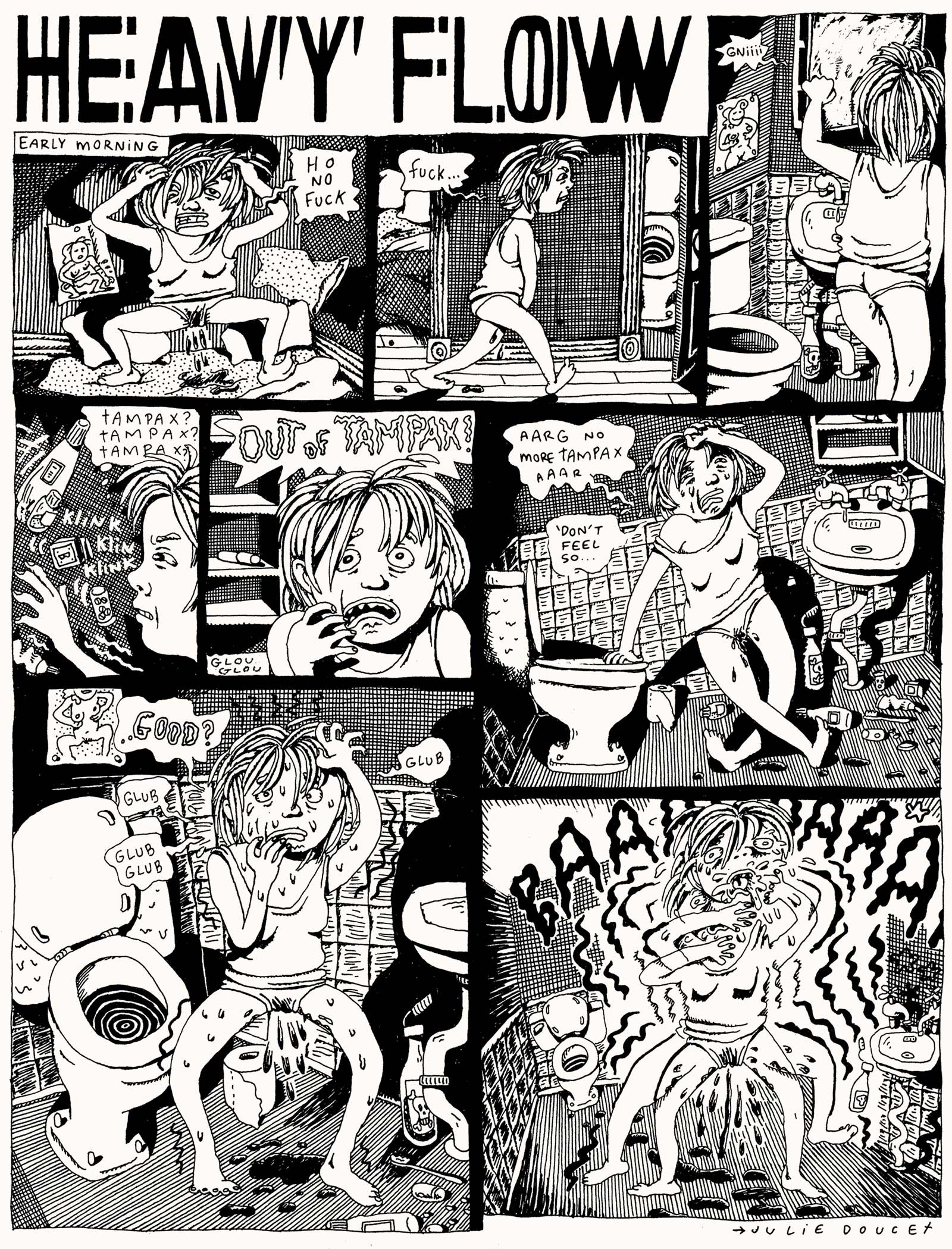

Nor are any subjects off-limits. In the first issue, Doucet levitates from the bed to the bathroom to change a tampon (period maintenance as a mind-body problem). In the second, a prostitute undresses and reveals herself to be a man, who, by unzipping his skin, transforms into a wolf; the wolf turns itself inside out to become a snake that coils up the waiting john’s leg and gives him a blowjob. In a dream recorded in issue six, Doucet sees her reflection in a mirror, and her double comes alive. The original Julie wills herself to turn into a man, her reflection breaks free from the mirror, and they have sex.

Twenty years after publishing the last issue of Dirty Plotte, Drawn & Quarterly has gathered the first dozen issues along with Doucet’s early, unpublished, and previously uncollected work, and numerous appreciations, in a two-volume slipcase edition, Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet. Such lavish treatment can’t dispel the unruliness of Doucet’s project; these comics are as pertinent and captivating today as when they first made their way into the culture (an occasion marked by “a thrilling mix of recognition and horror,” recalls the cartoonist Laura Park). Doucet’s parodic depictions of intense violence are still unsettling; her elastic treatment of sex and gender is still daring; and her open-ended treatment of female identity is still vital. She has said that from 1988 to 1990, “I was not questioning what I was doing… It was so unconscious, so directly my mind on paper.”

She gives free rein to complexity and contradiction—and to an athletic id. The unabashed world in her comics isn’t the real one (men in our realm don’t have vaginas surgically implanted into their foreheads, or not yet), but even reality, in Dirty Plotte, is phenomenologically fraught. A five-page story about a disturbing dream in which naked men aggressively invade a picnic and invite Doucet to “taste my croissant” (a literal croissant, but strategically placed) transitions into a waking state in which every inanimate object in her apartment comes alive with murderous rage. “Good ol’ reassuring reality!” she shrugs. But if the environment of Dirty Plotte is acutely Doucet’s own—relying primarily on dreams, fantasies, and imagined scenarios starring a version of herself—it is also freewheeling enough that readers, particularly women, can recognize something of themselves in it. The cover of every issue features possible versions of Doucet: a deranged artist, an old woman in the desert, a small figure lost in the big city. Issue three shows a group of Julies sobbing, laughing, anxious, and aloof—a scene she dubs, on the back cover, “Me, Myself, and I.” That multiplicity appears again in 1995 as a trio of weeping cartoonish Julies on the cover of My Most Secret Desire, which gathers Doucet’s dream comics. As the writer Deb Olin Unferth put it, “All I had to do was see the cover to know this cartoonist had stepped into my subconscious and found me cringing and giggling in a corner.”

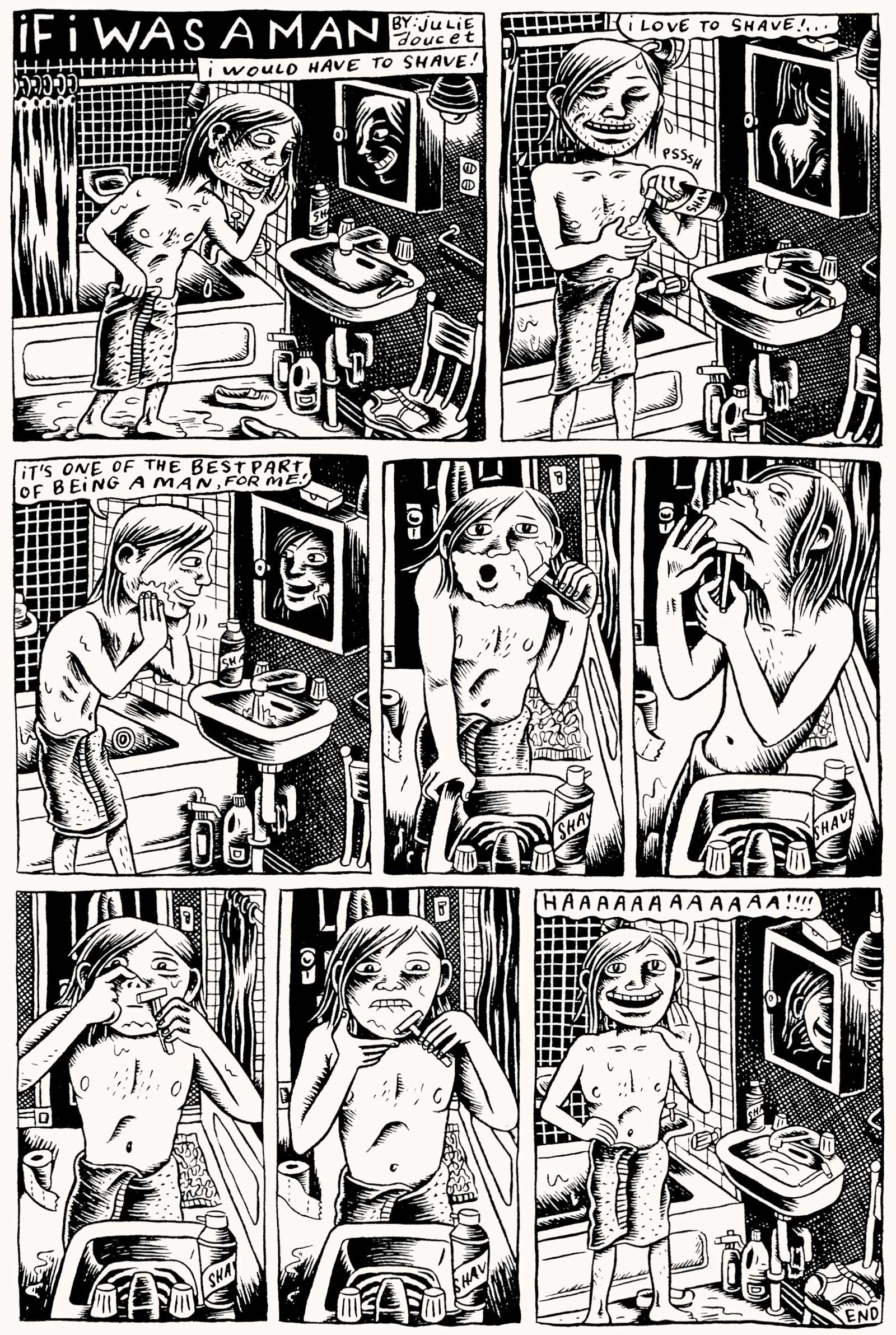

Each issue of Dirty Plotte occupies that peculiar nexus of cringing and giggling. At the moment when a gag comic might end, Doucet pushes further, into uncomfortable territory. The step-by-step instructions in the four-panel “Do It Yourself: Laugh!” conclude not with a lively chuckle but with an unhinged, sputtering roar. But in calling out her fantasies and fears with words and pictures on the page, Doucet uses transgression to carve out a space of power and freedom. She revels in the joy of unfettered exploration, and her enthusiasm buoys otherwise dark subject matter. A trio of strips called “If I Was a Man” begins by conjuring aggressive male sexual behavior (when male Julie muses dumbly on “the great mysteries of nature” after ejaculating on his girlfriend, it’s hard not to read it as a pointed commentary on the outsize male fantasies present in so many comics). But the series ends with idiosyncratic fantasy: the “useful” penis that can store small items like pens and rolled-up magazines and the “romantic” penis that begets flowers.

Advertisement

Vaginas, too, get full treatment. Plotte is Québécois slang that can refer derogatorily to a woman’s vagina and to the woman herself. Co-opting this term is the linchpin of Doucet’s rowdy perusal of femaleness. If plotte refers to a woman’s body, then Doucet refashions that body. In a what-if strip about breast cancer, she chooses a double mastectomy, then adds a pair of gold rings “for a joyous sucking.” And if plotte refers to the objectification of women, Doucet turns the ferocity of male scrutiny back onto men themselves. An audacious example is the four-panel “Self-Portrait in a Possible Situation,” in issue two. In three of the panels, she slices herself with a razor blade while posing suggestively. In the fourth panel, she addresses the strip’s voyeuristic reader: covered in bandages and seated before an assortment of knives, she portentously petitions her male readers to act as models “for some little drawings! Heh heh heh.” The tit for tat comes to fruition an issue later, in “Strip Tease of a Reader,” in which she kills and fastidiously dismembers “Steve,” a reader who has proffered himself.

Doucet has said that the idea for “Strip Tease of a Reader” came from a French magazine, L‘Écho des Savanes, that asked its male readers to photograph their girlfriends performing a strip tease. “And people did it,” she says. “In every issue, there was a full page with about six Polaroids of girls stripping.” Doucet’s version is a parody—violent, but with a wink. She turns it into a burlesque performance by herself and Steve, implicating him in the farce, even ending the strip by scrawling “Fin“ on the wall with the blood of his dismembered member. The viciousness in her reversal is slyly subversive. If the girlfriends in L‘Écho consented to participate, so too does Steve. And if the titillation in a woman‘s strip tease is the measured revelation of flesh, so too is Steve‘s.

The bite and blood in Doucet’s comics were stirred in part by provocative French bande dessinée—for instance, by Claire Bretécher’s playful satires of self-involved French life, Nicole Claveloux’s surreal and erotic subversions, and F’murr’s absurdist parodies, as well as other, more “risqué” comics published in the French magazine Pilote, to which her mother subscribed. Doucet’s distinctiveness is equally due to her highly graphic drawing style: packed, rambunctious black-and-white panels depicting cramped interiors swarming with bric-a-brac and busy street scenes alive with eccentric humanity. Her dense shading and hatching, which produce moody, high-contrast drawings, become more finely rendered and more articulate in later issues. Doucet’s American antecedent is Aline Kominsky-Crumb, whose comics, beginning in the Seventies, are predicated on exploring the raw corporeality of the female body: masturbation, defecation, hunger, pain, and pleasure. But Doucet didn’t discover the American underground—its men or its women—until Dirty Plotte was underway. Still, earlier generations of North American women cartoonists saw in Doucet a kindred spirit. Kominsky-Crumb included Doucet’s Dirty Plotte comic “Heavy Flow,” in which a Godzilla-size Doucet floods a city with her menstrual blood, in issue number twenty-six (1989) of the comics anthology Weirdo, which Robert Crumb had begun in 1981. The cartoonist Phoebe Gloeckner selected three short comics by Doucet that same year for an issue of the long-running all-female anthology Wimmen’s Comix, where they appeared alongside work by trailblazing underground cartoonists Diane Noomin, Lee Mars, Sharon Rudahl, and Kominsky-Crumb (as well as a young Alison Bechdel).

Remarkably, Doucet’s comics found an enthusiastic, if awe-struck, fan base among men. Dirty Plotte’s letter columns teem with appreciative notes from male readers, and Doucet’s male contemporaries were among her most ardent admirers. The cartoonist John Porcellino discovered Dirty Plotte through the international review directory Factsheet Five in 1989 and launched his own single-author zine, the minimal King-Cat Comics, two months later, inspired by Dirty Plotte’s monographic verve. In 1990, the Canadian cartoonist Chester Brown plugged Dirty Plotte issue one as “the comic book event of the year” and, a year later, moved his own provocative, sometimes taboo-busting comic, Yummy Fur, to Drawn & Quarterly. Seth, another Canadian cartoonist, approached Oliveros about publishing his poignant new autobiographical series Palookaville the month the first issue of Dirty Plotte came out, and it became Drawn & Quarterly’s second series. Adrian Tomine, a high school student in California in the early Nineties, who would go on to become a New York literary darling, saw “infinite possibilities” in the Dirty Plotte comics; Optic Nerve, which Oliveros began publishing in 1995, was his response. The boys’ club that was Drawn & Quarterly’s early stable—Brown, Seth, Tomine, and Joe Matt—largely developed around Doucet’s work, an implicit argument against the persistent “great masters“ notion of artistic production. Doucet, though perhaps lesser known today than many of her stablemates, was a central figure in the nascent alternative-comics scene. Oliveros has called her “the foundation of Drawn & Quarterly,” and it was his founding intent to publish comics by and for women.

Advertisement

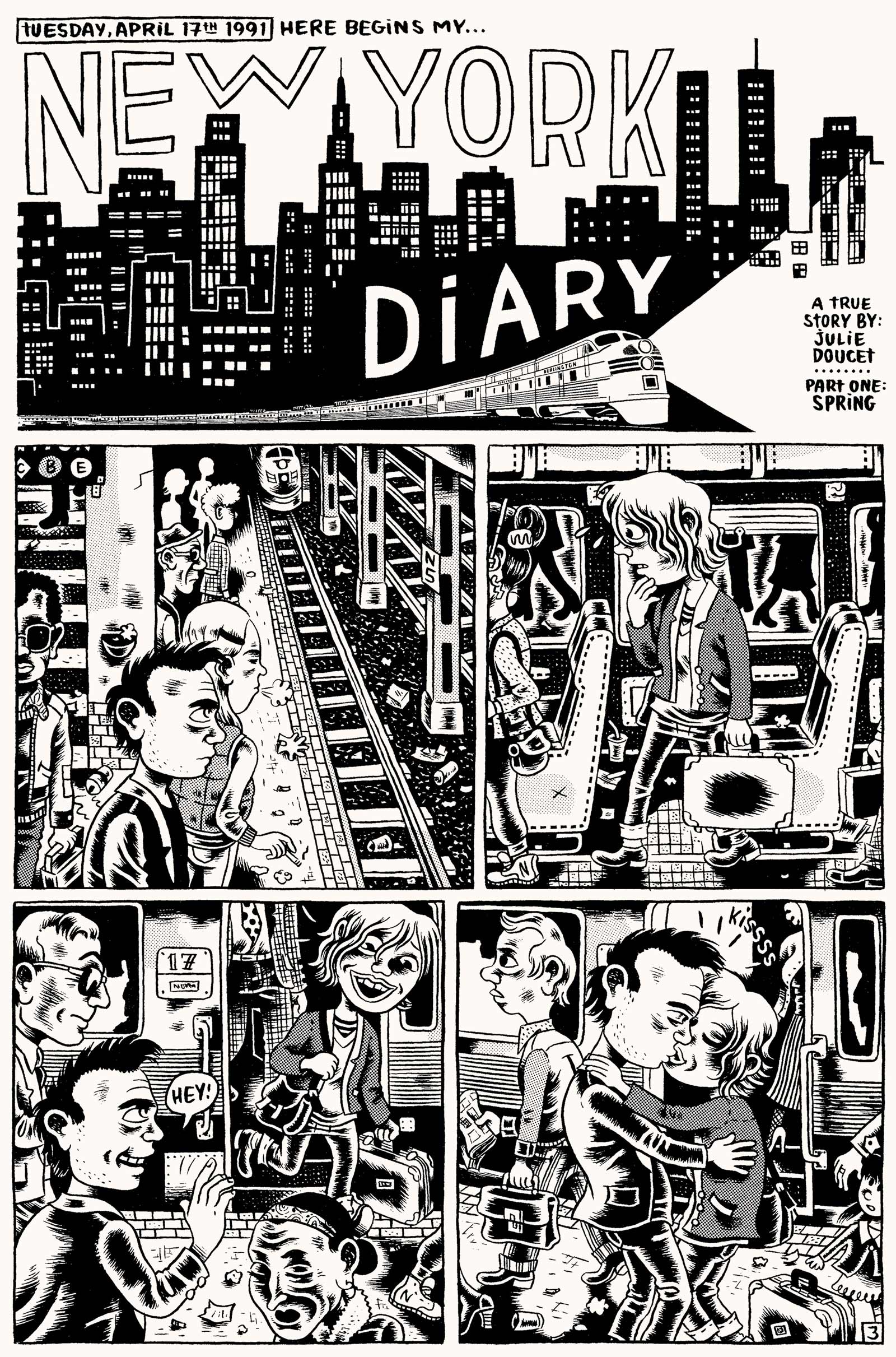

Most of the final three issues of Dirty Plotte are given over to “My New York Diary,” a self-contained story about Doucet’s year-long stay in New York, where she abruptly moved in 1991 after falling in love there. The story (published as a standalone book, with some additional material, in 1996) charts her time with her lover in his seedy apartment, as the initial bloom of romance is dulled by his resentment at her successes and his overbearing dependence on her, as well as her health problems and the difficulty navigating what she finds to be a “merciless” city. In the end, she leaves the man and the city, with no regrets. “My New York Diary” is the most extended comic in Dirty Plotte; it is one of the very few that is straight autobiography, that is told in hindsight, and that follows a traditional narrative arc. It is a work of realism, yet its nuance and honesty, about female identity, agency, and representation, could not exist without the experimentation that preceded it; “My New York Diary” gathers those earlier ideas in order to spin out its tale of romantic and worldly experience. The comics of Dirty Plotte are indeed complete. Doucet quit making comics altogether a few years after concluding the series (her interest in text-and-image combinations persists in her recent collaged photo comics). Yet they remain, as a fifteen-year-old burgeoning cartoonist Geneviève Castrée once discovered, “a parallel world about home, a world away from home.”

Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet is published by Drawn & Quarterly.