Cynthia Gleason, a weaver at a Rhode Island textile mill, went into her first trance in the fall of 1836. According to her mesmerist, a French sugar planter and amateur “animal magnetist” named Charles Poyen, she had been suffering for years from a mysterious illness; he called it “a very serious and troublesome complaint of the stomach” in one account and “a complicated nervous and functional disease” in another. For months Poyen had been giving lectures insisting that mesmerists like himself had mastered a technique for putting people in somnambulistic trances, curing their diseases, and managing their minds. When Gleason’s physician called him in to make magnetic “passes” over her body with his hands, Poyen wrote in his dubiously self-serving memoirs, she said she’d “defy anyone to put her to sleep in this manner.” But after twenty-five minutes, “her eyes grew dim and her lids fell heavily down.”

The next day, he reported, she said she felt better. Her sessions attracted more and more local interest; within a week, Poyen was putting her to sleep in front of groups of “distinguished gentlemen” and challenging the spectators to wake her up. (In Providence, they rang “a large tavern bell” next to her ear, put “a bottle of ammoniacal gas” under her nose, and shot a pistol “within five feet of her head.”) By February Poyen and Gleason had gone on tour, giving more private lectures and three public performances. He claimed, unpersuasively, that she refused “any pecuniary reward” except room, board, and “the means of satisfying the strict necessities of life.”

Before long, the mesmerism they exhibited had become the object of fevered speculation and imitation across New England and New York. Gleason could make oracular announcements from within her trance states; physicians started asking her to diagnose difficult cases. “This power is also the most constant and certain we have observed in her,” Poyen wrote. “Out of nearly 200 patients, of all descriptions, she has examined within eight or nine months, I have known but two or three failures.” He himself was rarely in good health and claimed that, at one point, Gleason had given a precise summary of his nervous disorders, including a suggested treatment. Moments like those, the literary scholar Emily Ogden argues, suggested that the rapport could go two ways: “In the case of Gleason’s diagnosis of Poyen, who controlled whom?”

Control is a coveted possession in Credulity, Ogden’s illuminating recent study of American mesmerism. The mesmerists and skeptics she studies all seem to want it; at any rate, they want to consider themselves rational and self-possessed enough not to fall under anyone else’s. During this brief, strange moment between 1836 and the late 1850s, mesmerizing another person—or seeing someone get mesmerized, or denouncing mesmerists as charlatans—became a way of stockpiling control for one’s own use.

At whose expense? One of Ogden’s welcome interventions is to extract mesmeric subjects from the disdain they received in their own time and the obscurity into which they’ve since fallen: the unidentified, enslaved West Indian laborers Poyen’s fellow planters tried to mesmerize in Guadeloupe; the female factory workers of whom Gleason was only the most famous; freelance clairvoyants like Anna Quincy Thaxter Parsons (Ogden thinks she worked “without the aid of a mesmerist”), who after touching a sample of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s handwriting called his mind “a circle with a dent in it”; and disabled somnambulists like Lurena Brackett, a blind woman who, when her would-be debunker urged her on a mental trip to New York, offered to “fly” him there.

Some somnambulists were men—according to Ogden, the Brook Farm resident Marianne Dwight found her future husband “very impressible”—but it was the women who seemed to inspire the most attention. (David Reese’s 1838 treatise Humbugs of New-York and an anonymous 1845 pamphlet, The Confessions of a Magnetizer, both depicted mesmerism as a threat to the virtue of young female subjects from “respectable” families.) Few of these women published accounts of their mesmeric careers. They make it to us buried under other people’s words through which their own flickers of defiance and shards of wit poke out. In Ogden, they’ve found a reader who commits not to identifying with their mesmerists or gloating over their disempowerment but to showing what elaborate techniques went toward trying to manage them and how unstable the resulting interactions could be.

To retrace their movements, Ogden has to read between the lines of letters, medical reports, newspaper stories, and eyewitness testimonies, often by the men who mesmerized or studied them. What lie under those smug performances tend to be fitful, skittering displays of anxiety, less over the risks to which mesmerism might have exposed its subjects than over the clairvoyant powers it turned out to give them. When Nathaniel Hawthorne’s fiancée, Sofia Peabody, told him she wanted to test her impressibility to mesmerism, he wrote her a panicked reply:

Advertisement

I am unwilling that a power should be exercised on thee, of which we know neither the origin nor the consequence… there would be an intrusion into thy holy of holies—and the intruder would not be thy husband! Canst thou think, without a shrinking of thy soul, of any human being coming into closer communication with thee than I may?—than either nature or my own sense of right would permit me? I cannot.

It hardly seemed to reassure Hawthorne that Peabody had wanted to put herself under the influence not of a mysterious man but of one of her close friends, Cornelia Park, who, according to Peabody’s biographer Megan Marshall, “had turned to the occupation in some desperation” after her husband left for California.

Some mesmerists seemed to provoke defiant responses precisely to make a show of suppressing them, as in the case of the “Mrs. R” who “proceeded to vindicate in an eloquent manner the rights of her sex” when her mesmerist “excited the organs of self-esteem,” but then despaired that she was “only a poor weak woman” when he turned to those of humility. And yet, even in the version of that story told by three local men who observed her case, when she woke up she seemed to take a kind of sly satisfaction at having thunderously denounced “the monster, Prejudice, that man has erected as a barrier around woman.” She “looked up” during a break “and, with a smile, said, in a natural tone, ‘I fear, gentlemen, I have acted very foolishly.’”

*

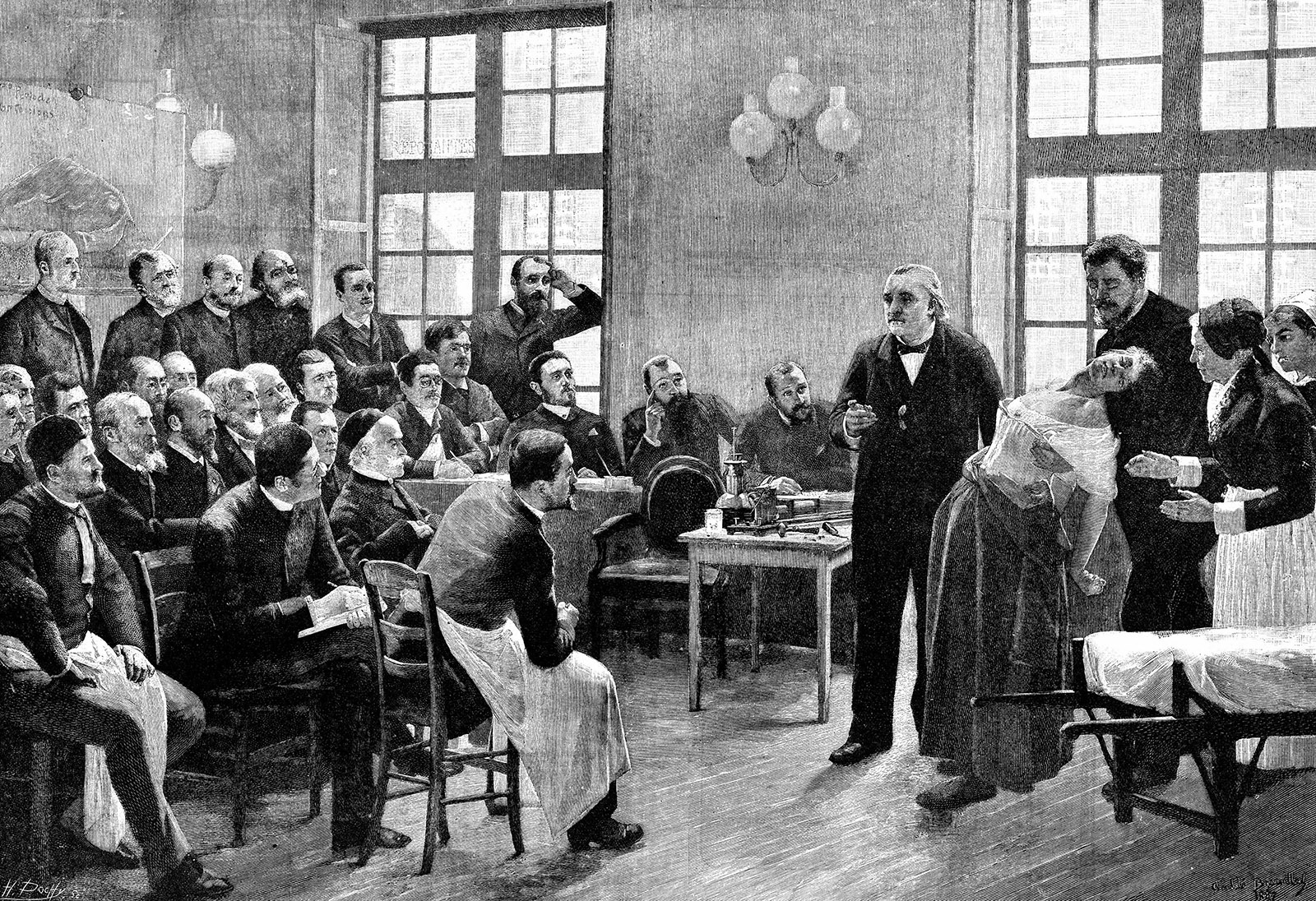

Mesmerism was a belated import. In the late 1770s, the German physician Franz Anton Mesmer claimed to have discovered an invisible vital substance that coursed through his patients’ bodies. In one formulation, according to the historian Jessica Riskin, it became “a fluid from the stars that flowed into a northern pole in the human head and out of a southern one at the feet.” At his clinic in Paris, he promised to cure a wide range of illnesses by clearing up blockages to the movement of the magnetic fluid; one notice mentioned “dropsy, paralysis, gout, scurvy, blindness,” and “accidental deafness.” Everything about his salon “was designed to produce a crisis in the patient,” the historian Robert Darnton wrote in his Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France (1968):

Heavy carpets, weird, astrological wall-decorations, and drawn curtains shut him off from the outside world and muffled the occasional words, screams, and bursts of hysterical laughter that broke the habitual heavy silence… Every so often fellow patients collapsed, writhing on the floor, and were carried by Antoine, the mesmerist-valet, into the crisis room; and if his spine still failed to tingle, his hands to tremble, his hypochondria to quiver, Mesmer himself would approach, dressed in a lilac taffeta robe, and drill fluid into the patient from his hands, his imperial eye, and his mesmerized wand.

In 1784 a commission, of which Benjamin Franklin was one of the chairs, issued a withering report about Mesmer that denied the existence of the magnetic fluid and emphasized his patients’ credulity. It circulated widely in the US. Among Americans, Ogden shows, for the next half-century “mesmerism was best known as a falsehood.” During the second half of the 1830s, however, it surged back into prominence. It split the London medical establishment—the late historian Alison Winter’s far-reaching 1998 study of Victorian mesmerism, Mesmerized, fills in Ogden’s story with the one from across the Atlantic—while Poyen and his successors were spreading it across New England.

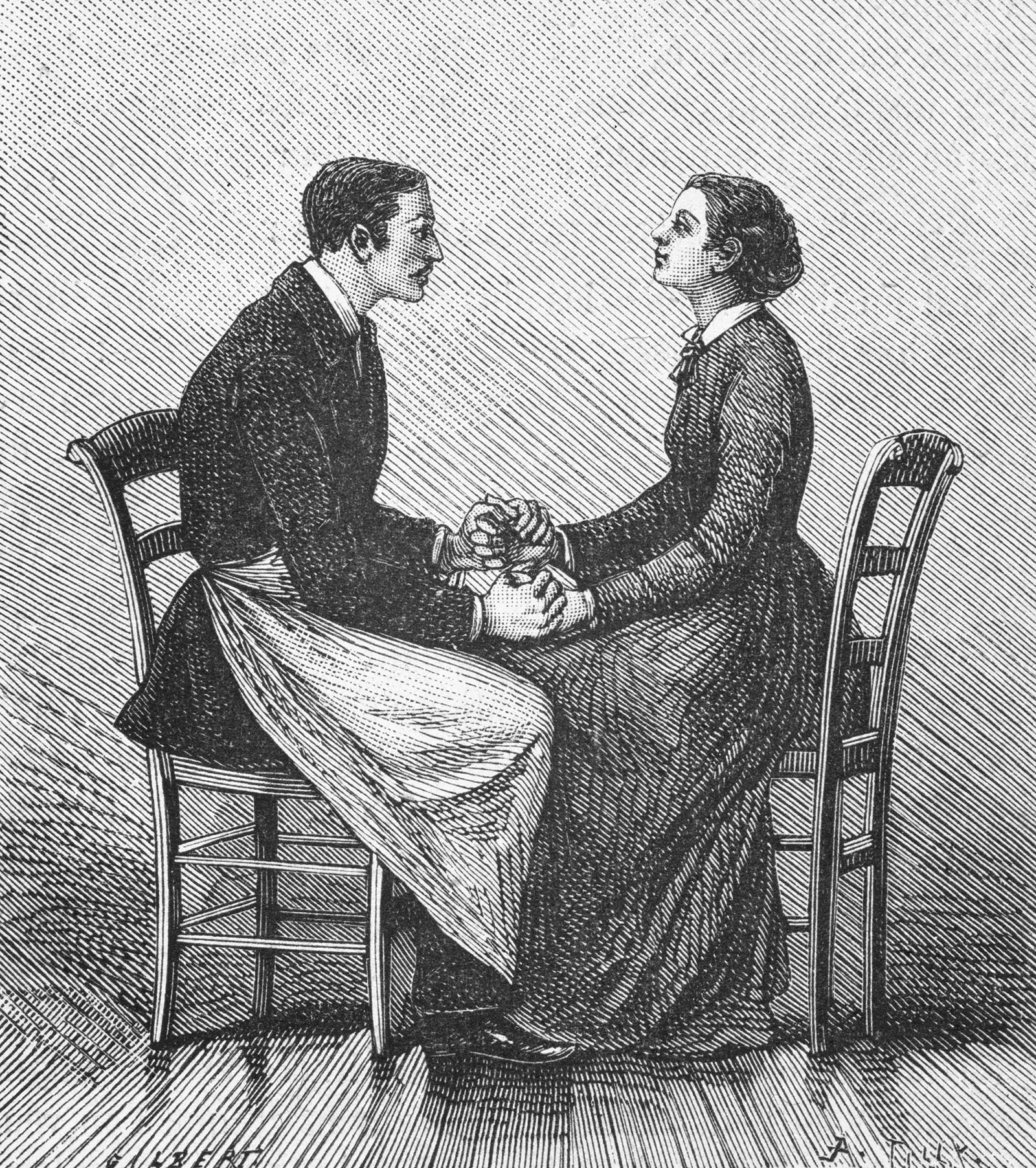

By then the method had changed. Poyen was drawing less on Mesmer than on his pupils Joseph-Philippe-François Deleuze and the Marquis de Puységur, who had modified their teacher’s approach. “Convulsions and expectorations became a thing of the past,” Ogden writes. “Instead, the fluid now produced somnambulism, a trancelike state in which subjects became credulous toward their mesmerists’ suggestions and obedient to their commands, sometimes developing clairvoyant powers.” In his 1825 how-to manual, Practical Instruction in Animal Magnetism, Deleuze argued that you could put your subjects in trances—cure their diseases; prepare them for painful surgeries; give them visions—by pinching their thumbs and then hovering your fingers over their face and limbs.

It was a matter of delicacy and lightness. You needed to move over the subject’s body “from the head to the extremities,” giving your movements little garnishes—a turn, a sweep, or a slight shake of the fingers—on each pass. By the end, you and your subject should have developed a rapport of almost dangerous intensity without any direct touch. In an appendix to the guide’s English translation, which appeared in the fall of 1837 from a Providence publishing house, New England practitioners reported that Deleuze’s technique could be used to treat epilepsy, cases of “fever and ague,” accumulations of bile in the liver, delirium tremens, “disturbed and unrefreshing slumbers,” toothaches, hip and back pain, nerve spasms in the face (tic douloureux), bronchitis, paralysis, and “the croup.”

Advertisement

It was also promoted to regulate precisely what the Franklin commission had said its believers had too much of: imagination. Ogden argues persuasively that mesmerists made gains in America not by denying that they exploited “credulous” subjects but by advertising that they had found a new technique for doing precisely that. Once calling people credulous emerged as a way to justify singling them out as test subjects, mesmerists could compete over “experimenting with, and hoping to control, the credulity of others.” They became businesslike experts in the profitable arts of human manipulation:

Was the mesmerized subject fantastically obedient? Then mesmerism could help discipline workers. Was the subject clairvoyant? Then he could speedily communicate the price of cotton from north to south. Could the subject read minds? Her insight might aid in educating young people. All of these uses were proposed; the first and last were attempted.

Two of mesmerism’s early adopters, Ogden shows, were plantation owners and factory managers. In his memoir, Poyen claimed that he had left Guadeloupe, where his family ran what he called “a large sugar plantation with many slaves,” because slavery was “as repugnant to my sympathies as adverse to my doctrines.” But Ogden’s research at the Archives nationales d’outre-mer in Aix-en-Provence showed that he “can be confidently identified as the joint owner” of the plantation, Le Piton, and that he inherited a number of enslaved men and women when his father died in 1827. On a trip back to Guadeloupe in the mid-1830s, he claimed to have come across other planters using Deleuze’s manual to mesmerize the people they enslaved. From what few sources remain, Ogden finds that one such planter tried to use “magnetic enchantment as a surveillance technique” and boasted in a letter to Deleuze that an enslaved somnambulist had “informed him of everything that happened on his plantation.”

Poyen had his first success as a mesmeric lecturer several years later in Pawtucket, the birthplace of the American textile mill. “Poyen’s lectures there,” according to Ogden, “cost seventy-five cents a ticket”—too much for most of the workers—“so it is likely that his audiences were made up mostly of owners and managers.” One of those audience members was not only “the part owner of a mill along Sargent’s Trench” but also Gleason’s physician. Under Poyen’s influence, Gleason seemed to stay asleep even under the most disruptive conditions and awoke at “eight o’clock exactly.” It was, Ogden points out, “as though he were demonstrating that magnetism could make workers internalize factory schedules.” When she opened her eyes at the end of their first onstage demonstration, she said she felt “bright as a dollar.”

*

And yet Ogden finds that “magnetism never became institutionalized in the factories.” Some workers found new uses for it. “A few of us were interested in Mesmerism,” Harriet Robinson wrote in Loom and Spindle, her 1898 memoir of working as a factory girl in the mills of Lowell, Massachusetts. “Those of us who had the power to make ourselves en rapport with others tried experiments on ‘subjects,’ and sometimes held meetings in the evening for that purpose.” In an editorial for the Lowell Offering from 1845, a factory worker named Jessie proposed—perhaps as an elaborate joke, or as a comment on the mills’ system of social control—using mesmerism as a sort of experience machine to trick the poor and hungry into thinking they were well fed and clothed. “Let the wretched, at least, bask in the smiles of imagination; and let them be willed to eat and be warm,” she wrote:

Instead of soup-houses and poor-houses, let the wise administrators of our laws engage some willing well-clad and well-fed Mesmeric Professor to exercise his skill, and will, for the benefit of the destitute… And let the cold, influenced by his compelling power, wander beneath green bowers, and fragrant shades, in sunny climes.

The technique that never caught on as a form of labor control seemed to get more attention as a public spectacle. When Poyen left for France around 1839, his successors fought over the market he had opened up. According to the historian Ann Taves, a brash Englishman named Robert Collyer called his competitors “hundreds of ignorant mechanics, carpenters, painters, furriers, scavengers, barbers, and other ‘unlettered cubs.’” Like Collyer, the Kentuckian James Rhodes Buchanan at first practiced “phreno-mesmerism,” in which the mesmerist mapped and manipulated the “phrenological organs” practitioners of that pseudoscience thought comprised the subject’s brain; before long, he started enlisting the clairvoyants he mesmerized to measure the character of third parties by touching samples of their handwriting.

By the late 1840s, mesmerism had grown more new branches. Traveling “electrobiologists” played tricks on their entranced subjects without, Ogden points out, invoking any of the medical, moral, or spiritual benefits earlier mesmerists had promised. Broadside ads for their demonstrations promised pranks: “A WALKING STICK will be made to appear a SNAKE! The taste of WATER will be changed to VINEGAR, HONEY, COFFEE, MILK, BRANDY, WORMWOOD, LEMONADE, &c. &c. &c.” Meanwhile, other clairvoyants had started conversing with spirits, including, at Brook Farm, that of the utopian communitarian Charles Fourier. One of these clairvoyants, Andrew Jackson Davis, turned into a central figure for the phenomenon that became known as Spiritualism.

That movement has tended to get more attention than the mesmeric experiments it drew on. In her influential book Radical Spirits (1989), Ann Braude argued that “the spread of women’s rights ideas in mid-century America” owed much to Spiritualists who addressed men in public and campaigned against domestic violence and denounced the entrapment of women in constraining marriages. An 1868 editorial in the Spiritualist Banner of Progress demanded “nothing short of giving woman the right to control her own person.”

*

Mesmerism seems to have rarely lent itself to such an emancipatory politics. It comes off in Credulity as a grimmer business than Braude’s Spiritualism, heavier with cruelty, always stressing how hard it is to get out from under forces you can resist but not demolish. Braude had lingered on characters like the trance speaker Achsa Sprague, outspoken advocates for personal freedom. (“‘You decidedly misunderstand me,’ she wrote to a newspaper to correct the impression that she taught free love. ‘I only spoke against the injustice of all Laws, the Laws of marriage among them.’”) Ogden gravitates toward figures like Brackett, who in this account spent more time in her letters considering “the choice between dependencies” than hoping for “absolute freedom from them.”

In the world Ogden evokes, freedom is usually partial and compromised. When she pauses over the famous session during which Brackett converted a prominent skeptic named William Leete Stone, she warns against assigning Brackett all of “the controls that Stone had seemed to operate.” Instead, she suggests that Brackett’s rapport with Stone—a newspaper editor who took an interest in the blind clairvoyant and borrowed “the power of enjoying her exclusive company” from her mesmerist—came down not to “one confidence man pulling the strings and one credulous dupe being jerked about” but to “two people playing cat’s cradle.” It became a “moment of collaboration.”

That last word strikes an unusually frictionless note after so many pages of contested manipulation. More often, the direct encounters in Credulity between clairvoyants and the men who mesmerized them seem less like collaborations than like competitions over who would set the terms of the session and whose interests it would serve. The subjects’ flashes of insight have a sharp-edged, glinting tone. They become ambushes against the mesmerist’s authority, ways of struggling for dependencies that give the somnambulist’s mind more room to move.

That struggle runs through the story of Brackett’s life, which Ogden reconstructs using archival holdings from the Perkins School of the Blind. She lost her sight in an accident at sixteen, suffered from chronic illnesses, and lived on the edge of destitution. Her mesmerist, George Capron, met her in Providence in 1837; she came to fame when she gave such a convincing account of a spiritual voyage to New York that Stone took up her cause.

“Her clairvoyance,” for Ogden, “freed her from others’ expectations that blindness would constrain her.” She read books, looked at pictures, strolled through houses with ease. “Sometimes,” according to one of the men who hosted her, she stayed “in the magnetized state ten or twelve hours.” She enjoyed one host’s private natural history museum so much, Ogden relates, “that she made a private visit after her public one was complete, asking to be magnetized overnight” to return to the collection. “There she strolled about like a ghost of refined tastes, admiring his ‘shells’ and ‘Chinese rice paper flowers’ at her leisure.”

Brackett spent six years at Perkins, where she befriended a younger deaf-blind boarder and endured harrowing medical treatments. After she left the school, she got by “precariously,” Ogden writes. “I shall make every effort to make my own living,” she wrote her benefactor, Samuel Gridley Howe. “If I find I cannot I suppose I shall have to submit to the galling chains of dependence.” Sewing brought in a fraction of the income she needed; she married her doctor in 1849.

When she was still at Perkins, Margaret Fuller came across her during a visiting day. Fuller remembered her from an encounter years earlier, when Brackett had been “in a very happy state” and instantly picked up on Fuller’s severe nervous illness. Brackett claimed not to remember her. But she passed Fuller a note: “The ills that Heaven decrees / The brave with courage bear.” For Fuller, “those pencilled lines, written in the stiff, round character proper to the blind,” became a mark of insight. “The blind girl perhaps never knew who I was,” she wrote, “but saw my true state more clearly than any other person did.”

Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism, by Emily Ogden, is published by Chicago University Press (2018). This essay is indebted to the suggestions of David Blight, Erica Getto, and Jessica Marion Modi, and to Alanna Hickey for the quotation from the Lowell Offering.