I put off beginning the poet Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights, which was published earlier this year, because I was afraid it would end too quickly. I felt sure that the book’s 102 essays, most between one paragraph and three pages in length, would be kin to his poems, which are tender, tactile, and human, whether he’s celebrating the spastic joy of listening to a good song (“drift / of hip oh, trill of ribs, / oh synaptic clamor and juggernaut / swell oh gutracket / blastoff and sugartongue”) or articulating a swelling fury, as he does in the evocatively titled “Within Two Weeks the African American Poet Ross Gay is Mistaken for Both the African American Poet Terrance Hayes and the African American Poet Kyle Dargan, Not One of Whom Looks Anything Like the Others.” They are poems about being alert to the world and feeling ripe for play and wonder.

Gay wrote the book’s essays (and many others that didn’t make it into the final draft) over the period of a year, one each day, for the simple reason that he thought it would be nice to write about delight every day. The handful of rules he set out for himself included composing the essays quickly and writing them by hand. I decided to read one entry from the book each day, to follow the model of how he’d written them and to give each entry its own space to unfold in my mind—to let it warm me, I’d come to realize, like sunshine.

The first time I blew it was with entry thirteen. I read entry twelve, on nicknames, and browsed Gay’s litany of aliases (Bizquick, Biz, Big lil Big, The Big Gay, Sossy, Saucy, Snozzers, and on and on) and thought, as I did so, about the fact that I’ve only had one nickname my entire life, used by only one person (if this sounds lonely, it isn’t; it feels valuable, like a tightly wrapped secret). As I was thinking, I turned the page and just kept reading. But breaking the rules is allowable here, not least because Gay himself does it. For instance, he tasked himself with writing about one delight a day and forbade the hoarding of delights. Five months into his endeavor, however, he purges his accumulated list of delights (he refers to them, delightfully, as “layaway”) in order to be true to the temporality of the project. He spends an entry listing the overflow delights, and it’s almost too much to bear, so full is each tiny world:

My friend Evie Shockley, who told me, after I gave a reading where she teaches, that a turn in one of my poems, which in some poets I say might be a horseshit trick, is in fact a horseshit trick.

…

The phrase—a colloquialism (a regionalism?) not native to me—“I’m gonna get me some x,” which these days I myself occasionally employ. The understanding of a multiplicity of selves, of a complexity of self. A self-weirding. I does not equal me.

…

A quote from June Jordan’s response to the moon landing. “How about a holy day, instead, a day when we will concentrate on the chill and sweat worshipping of humankind, in mercy fathom.” In mercy fathom.

In another, he mentions that the cardinal is his favorite bird. I read this and looked out the window and saw a cardinal on a maple tree, hopping, crisscross, from one branch to another, before flying out of the frame.

In his notes for “an immense poem,” Walt Whitman thinks about “collecting in running list all the things done in secret.” Delight is a personal pleasure. Two people may delight in the same thing, but the feeling of delight doesn’t require another person. Left unshared as many delights are (especially the commonplace variety that Gay writes about), they live as a kind of secret. And not only a secret but a secret not often dwelt on—a fleeting secret. To catalogue delights and to delight in them at some length, as Gay does, shines a light on otherwise private, intimate moments, and the book that collects this catalogue has the feel of a devotional poem. Because Gay is a poet, it’s hardly a stretch to read his prose as versifying, and an attentive reader will notice moments of overlap between the concerns in The Book of Delights and Gay’s poetry. In the poem “Patience,” from his 2015 collection Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude (even the books’ titles are fraternal twins), he writes, “Call it sloth; call it sleeve; / call it bummery if you please; / I’ll call it patience; / I’ll call it joy this, / my supine congress / with the newly yawning grass.” And in Delights, he evangelizes the pleasure of lying down in public: on the grass and also on sidewalks, what he calls a “deviant” delight (or, if you please, a bummery joy).

Advertisement

But to return to devotion: it’s not simply that Gay has dedicated this book to a single idea—delight in its many forms—but that in its repetition, in his act of finding delight in rice candy, in music from a passing car, in babies on planes, and in a backyard log pile, it becomes an enthusiastic exercise in observance. Robert Walser wrote that “drafting a prose piece puts me in a devotional state of mind.” As I began to read The Books of Delights, I had occasion to rearrange one of my bookshelves in an attempt to squeeze in a few new books. In the process, I discovered—or rediscovered, since at some point I had put it there myself—a very slim book by Walser called Looking at Pictures. The discovery felt serendipitous. As Gay might say, it was a delight. What do these two books have in common? One answer is nothing. Another is, fundamentally, everything.

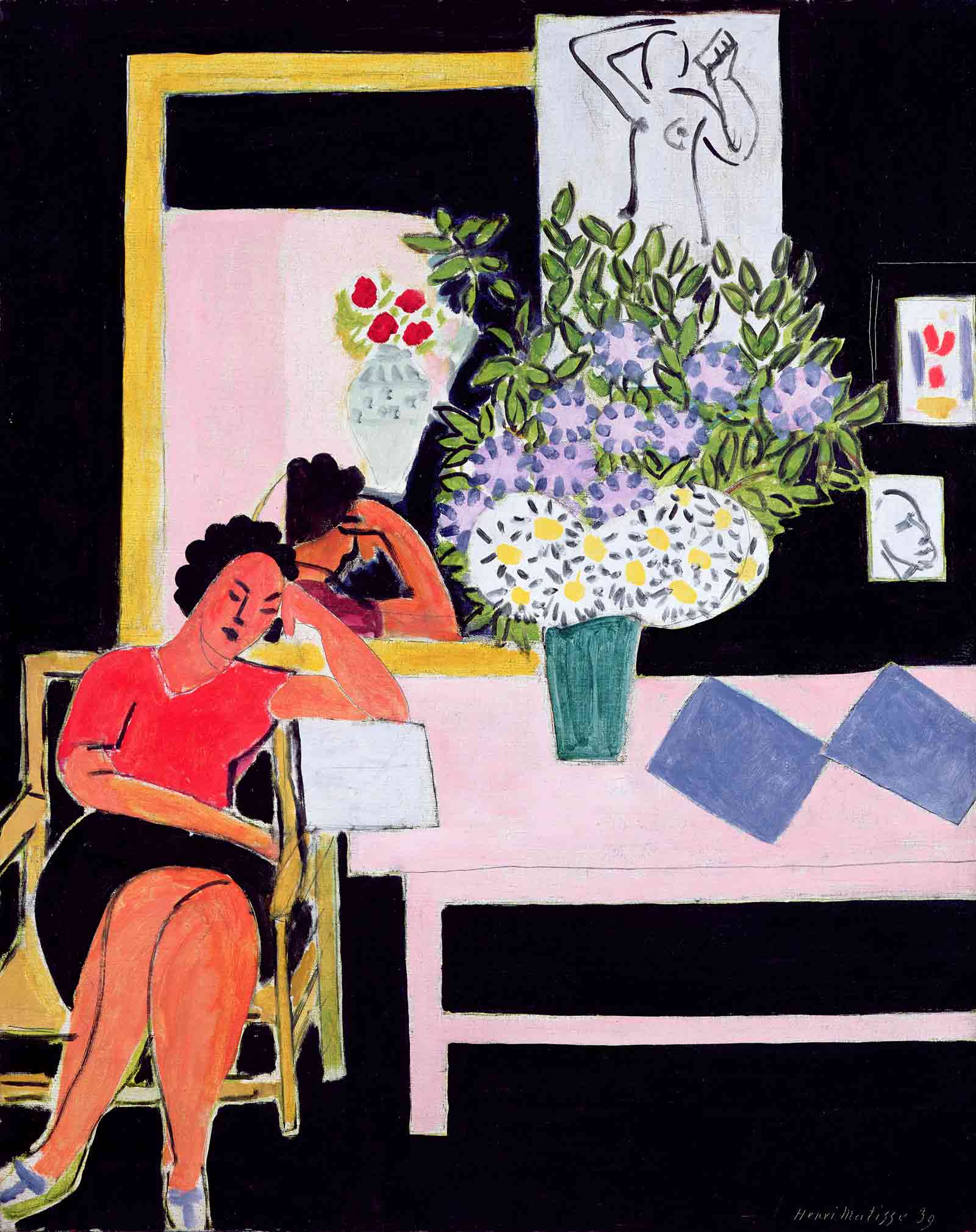

Walser’s book ostensibly contains essays on art, and he does look closely at individual works, homing in on details a less observant viewer might miss. But those compositional minutiae, brushstrokes, and colors inspire tangents and digressions that have very little, if anything, to do with the art. Walser’s essays are less studies of art than sideways contemplations of the observed world. “Great art resides in great goings-astray,” he writes. It isn’t just that Gay’s project runs, in a sense, parallel to Walser’s but that they seem to speak to one another, across time. Gay is Walser’s watercolorist who “paints cheekily, as it were, and at the same time documents his own good judgment, his feeling for what is.” Here is Walser on looking at a painting of a wintry forest scene:

You involuntarily put your hands in your pockets when you look at it, since it so wonderfully communicates its wintry nature. In the forest, a man is working, and you can see, can feel: the ground in the forest has frozen, and you can see far, far beyond the forest, the forest gives way to the most distant distance, and now I have perhaps not yet said everything that could be said about this picture, but you can certainly feel from what I’ve said here how greatly I admire it.

Gay helps me see that Walser doesn’t just admire the painting, he delights in it. The objects and activities Gay writes about elicit the same kind of feeling that comes to Walser through the “distant distance”; they are portals and portkeys for deeper emotions and profound memories and, in Gay’s case, for living a certain kind of life. “There is some profound lyric lesson,” Gay writes, “in witnessing an unfathomably beautiful event in the dark night, an event illegible except for its unfathomable beauty.”

*

I heard Gay read from The Book of Delights last October at the Dodge Poetry Festival in Newark, New Jersey. He had chosen the entry in which he is applying coconut oil to his body after a shower. He described the progression of oiling, from legs to face, as he considers what he is doing, why he does it, and what contemplating these things makes him think about. He writes, for instance, “Today when I watched myself, particularly when I was oiling my chest and stomach, which I do kind of by self-hugging, I was thinking how many bodies of mine are in this body, this nearly forty-three-year-old body stationed on this plane for the briefest.” I had come to the festival on high-school day, which meant that the large auditorium at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center was full of kids. When, early in the essay, Gay read the word “testicles,” the hall exploded.

Bodies can be poetical, but they can also be absurd, and in this essay Gay was working both of these perspectives. He moves from thinking about the particular brown shade of his skin to pondering the awkwardness of his position: “my leg up like this, bent over, my testicles swaying just beneath my pale thigh.” (The passage brings my mind to John Coplans’s photographic study of his own aging body. Interesting, too, that Coplans should think of his body as Gay does of his—as a vessel for other bodies, previous or alternative selves. “I don’t know how it happens,” Coplans once said, “but when I pose for one of these photographs, I become immersed in the past… I am lost in a reverie. I am somewhere else, another person, or a woman in another life. At times, I’m in my youth.”) The shock of Gay’s writing—and I wonder if I would have fully understood this if I hadn’t heard the work read aloud by Gay himself—is his seamless shift from breezy, affable observation to sober (and admittedly still affable) profundity. In the essay, the madeleine of his bent leg and pale thigh recalls for him Toi Derricotte’s poem “The Undertaker’s Daughter,” in which, as a child, she sees her abusive father in much the same position. “Seeing his testicles dangling like that,” Gay writes, “she thinks they are his udders, the ‘female part he hid, something soft and unprotected I shouldn’t see.’” It’s the kind of unexpected connection that will galvanize an auditorium full of giggling high schoolers.

Advertisement

I want to say that Gay’s writing is magical because that’s the way it feels when I read it. But the essays didn’t come into being with a flick of the wrist, a wave of the wand. Calling it magic undercuts Gay’s craft, the effort that goes into producing literature that feels as fluent and familiar as a chat with a close friend. His voice has integrity, in both senses of the word: a completeness or consistency, true to itself; and an honesty and compassion (“a compassion weeping and warbling from all the immediacies that surround us,” as Walser writes) so frankly subjective that it produces an incorruptible vision. Gay’s loose-limbed sentences diagram his delight, partaking in numerous asides—some as paragraph-long parentheticals—and equally numerous asides within asides, as well as nested subordinate clauses that are the purview of intimate conversation, not written prose. They are clauses and asides in which, as Gay writes them, you feel his hand on your arm, you feel him lean in toward you, conspiratorially or simply to emphasize his meaning.

On a flight from Indianapolis to Charlotte, a black male flight attendant brings Gay a drink and taps him twice on the arm. The delight of “warranted familiarity” spills out in a single, swiftly tilting sentence:

By which, it’s really a kind of miracle, was expressed a social and bodily intimacy—on this airplane, at this moment in history, our particular bodies, making the social contract of mostly not touching each other irrelevant, or, rather, writing a brief addendum that acknowledges the official American policy, which is a kind of de facto and terrible of touching of some of us, or trying to, always figuring out ways to keep touching us—and this flight attendant, tap tap, reminding me, like that, simply, remember, tap tap, how else we might be touched, and are, there you go, man.

Communication, for Gay, is sensory. Numerous entries involve his delight in eating food, his delight in smelling flowers, his delight in hearing birdsong. Delight is experiential. In “Song of Myself,” Whitman writes, “I loafe and invite my soul, / I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of grass.” The self at play in the physical world intoxicates Whitman. He writes later in the poem:

Clear and sweet is my soul, and clear and sweet is all that is not my soul.

Lack one lacks both, and the unseen is proved by the seen,

Till that becomes unseen and receives proof in its turn.

The Book of Delights is an extended engagement with this idea: the connection between an individual and the world through which and in which the self moves, and delight, for Gay, is the moment of recognition in which the unseen (those heretofore invisible or unappreciated elements of life) is perceived.

Gay’s book is a Whitmanesque project. Plenitude is woven into the fabric of his essayettes, and it is, at least occasionally, close to the surface of his mind, as when, in an essay on cuplicking (yes, the licking of drips left on a cup), he admires the “Whitmanian assertion of multitudinousness” in the phrase “today I found myself.” Whitman is on my mind because I’m writing this on the heels of his centenary, an occasion for remembering, too, that outside of his poetry Whitman fell short of his own radical ideas and wasn’t brave enough to extend his own bodily freedom to all bodies. His attitudes toward slavery were determined by the political threat to democracy—whether, for instance, abolitionism would imperil the Union—not empathy for the enslaved. What then does it mean to talk about the work of a black writer in relation to Whitman’s? Can we parse what’s good and important and useful in his poems? I wonder if June Jordan was circling the same questions when her essay “For the Sake of People’s Poetry: Walt Whitman and the Rest of Us” was published in 1980. When she identifies the democratic and pluralist “New World” spirit of Whitman’s poetry and its “reverence for the material world that begins with a reverence for human life,” I read this as a description of Gay’s work, too.

Poets who came after Whitman—particularly, in Jordan’s essay, poets of color and women—are his descendants but not his followers; they use the gifts of his poetry to create their own America, to “traceably transform and further the egalitarian sensibility,” Jordan writes. The project of the New World didn’t end with Whitman; it required, and requires, a true multitude:

I kept listening to the wonderful poetry of the multiplying numbers of my friends who were and who are New World poets until I knew, for a fact, that there was and that there is an American, a New World poetry that is as personal, as public, as irresistible, as quick, as necessary, as unprecedented, as representative, as exalted, as speakably commonplace, and as musical as an emergency phone call.

Any number of Gay’s poems fulfill this vision, though the first that comes to my mind is “A Small Needful Fact,” his keen and moving poem for Eric Garner. Garner sometimes worked for the Parks and Recreation Department, and Gay imagines him having cultivated plants that even now

continue to grow, continue

to do what such plants do, like house

and feed small and necessary creatures,

like being pleasant to touch and smell,

like converting sunlight

into food, like making it easier

for us to breathe.

*

Midway through The Book of Delights, Gay thinks about the song “For All We Know,” sung by Donny Hathaway, and the way death is woven into Hathaway’s soulful rendition:

Our imminent disappearance is Donny’s subject, his voice’s subject—which the voice’s first subject always is, as fading and disappearance are sound’s essential characteristics. His is a voice that makes you realize that your voice is the song of your disappearing, which is our most common song. The knowledge of which, the understanding of which, the inhabiting of which, might be the beginning of a radical love. A renovating love, even.

Do we love more when we realize that everything is finite? Does knowing that this book is finite, that it lives between two covers, make each moment with it that much more important? Could it be that delight is a radical, renovating love because it fills rather than consumes? And because, as Gay shows us, we are capable of feeling it every single day?

While listening to the first episode of the podcast Bughouse Square with Eve Ewing, I heard James Baldwin tell Studs Terkel in 1962 that he finds the word joy to be “terribly suspect.” His suspicion isn’t of the feeling itself but of its evocation in a racially unequal America: it is a trap, suggesting that “the Negro is ‘happy’ in his ‘place,’” as Baldwin wrote later that year, and that it would be socially irresponsible to advocate for a change that would help him “rise out of it.”

I followed these thoughts to The Fire Next Time, where Baldwin writes that “there is something tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged” in jazz, and in the blues in particular—that sad songs aren’t necessarily sad and happy ones happy. He writes that happy songs, for instance, contain elements of sadness and that the happiness plays off the sadness to heightened effect. Baldwin sees in this tendency a kind of sensuality that I find is ever-present in The Book of Delights. “To be sensual,” Baldwin writes, “is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.” It is a way of renewing oneself at the fountain of one’s own life, he continues, and a way of staying connected directly to reality, bypassing or omitting the “labyrinth of… historical and public attitudes.” (I’m thinking again of Gay’s deviant delight in lying on sidewalks.) It is a rediscovery or a reconnection with humanity and with joy, which Baldwin thinks of as an openness and unselfconsciousness associated with “a certain kind of freedom.”

The push and pull that Baldwin sees in jazz is in joy, too. Zadie Smith calls it “a human madness,” in her 2013 essay for the Review, “Joy.” Gay calls it “being of and without at once.” He wonders if joining our sorrows together, if shrinking the distance between our respective intolerable wildernesses (a confluence of terms by Smith and Gay) is joy itself. It is one answer that is as much a beginning as it is an ending:

Because in trying to articulate what, perhaps, joy is, it has occurred to me that among other things—the trees and the mushrooms have shown me this—joy is the mostly invisible, the underground union between us, you and me, which is, among other things, the great fact of our life and the lives of everyone and thing we love going away. If we sink a spoon into that fact, into the duff between us, we will find it teeming. It will look like all the books ever written. It will look like all the nerves in a body. We might call it sorrow, but we might call it a union, one that, once we notice it, once we bring it into the light, might become flower and food. Might be joy.

The Book of Delights, by Ross Gay, is published by Algonquin Books.