In Louisa May Alcott’s much beloved novel Little Women (1868), Jo March earns extra money writing low-brow sensational stories, or “blood and thunder tales,” as Alcott calls them. At the same time, Jo falls in love with the high-minded and serious Professor Bhaer, whom she one day observes reading a newspaper: “Jo glanced at the sheet and saw a pleasing illustration composed of a lunatic, a corpse, a villain, and a viper.” Jo thinks this horrifying tableau might, in fact, be an illustration for one of her own grisly stories. Bhaer crumples the paper up and tosses it into the fire, annoyed that such “bad trash” is published at all.

Jo panics, fearing that Bhaer might accidentally come across one of her drafts. She rushes upstairs and destroys her latest story: “Demon of the Jura.” In Alcott’s time, Gothic tales were often the only type of fiction that publishers would accept from women, whom their male editors considered to be extravagantly emotional and thus suited to the genre. Later in the story, Jo goes on to write a novel less mired in sensation and more rooted in her experience, a book not unlike Little Women.

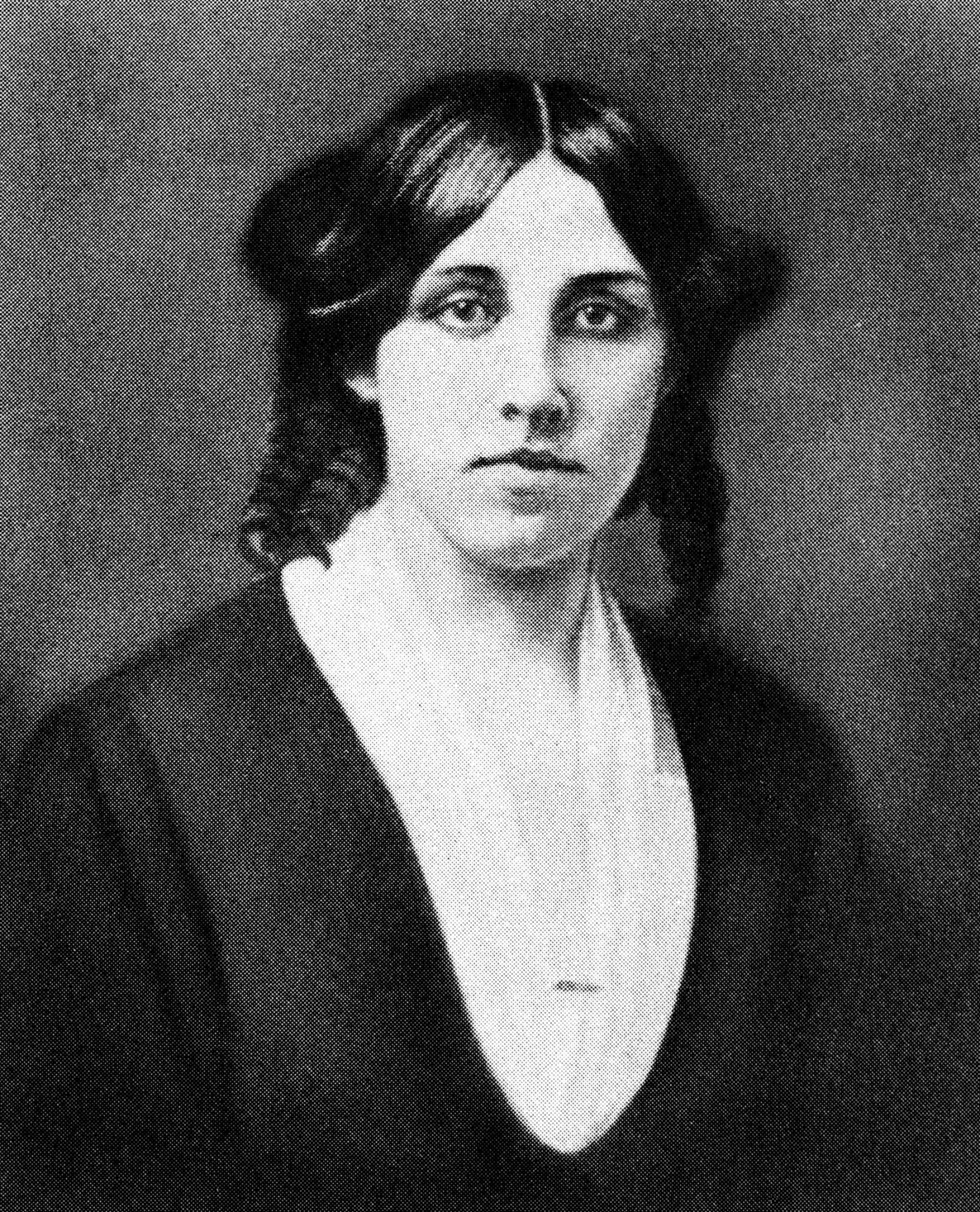

In this way, Jo’s life mimics Alcott’s own transition from a writer of garish thrillers to sentimental tales of everyday life. But Alcott’s creative transformation had less to do with winning the affections of a shy scholar and more to do with her time serving in military hospitals during the American Civil War. Alcott’s letters home from the front lines, later published as Hospital Sketches (1863), proved that her true gift lay not in inventing new worlds, but in observing the one around her.

Alcott’s family were ardent abolitionists. Her father, Bronson Alcott, was friends with William Lloyd Garrison, editor of the anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, and the Alcott home was at one point a stop on the Underground Railroad. One of Alcott’s earliest childhood memories was opening a stove and finding a runaway slave hiding inside. When the war broke out, Louisa was determined to contribute to the Union cause. On December 12, 1862, she arrived in Washington, D.C., where she had arranged to work as a nurse, an opportunity only newly available to women. Louisa spent six weeks working at the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, not the assignment she had hoped for. The Union had a reputation for being poorly managed and in ill repair, and Alcott wrote home to her family about the rotting wood floorboards and the swarming rats.

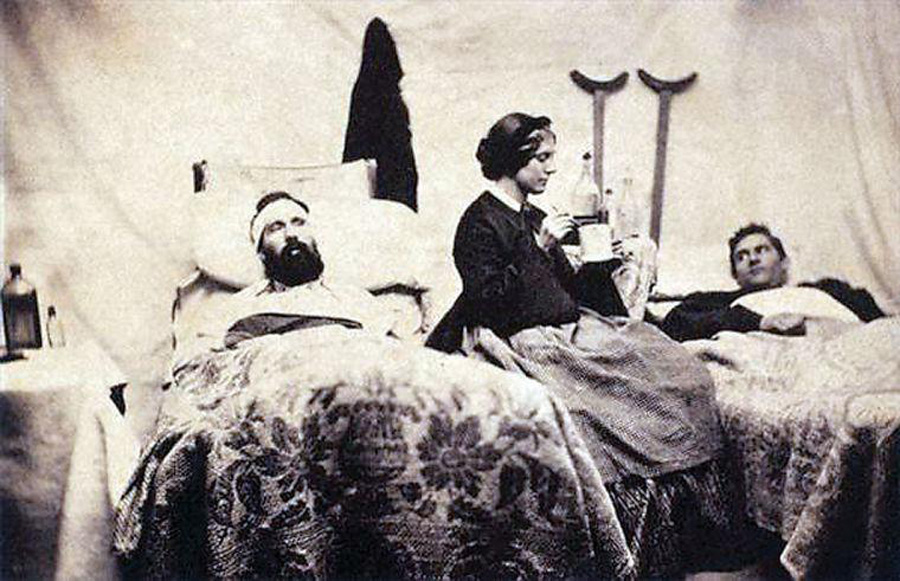

Shortly after she arrived, the hospital received scores of wounded soldiers from the bloody battles at Fredericksburg and Antietam: “3 or 4 hundred men in all stages of suffering, disease & death” she later wrote. Although women had been nursing the sick since time immemorial, it was only in the nineteenth century that their work became professionalized—thanks in no small part to reforms introduced during the Crimean War by Florence Nightingale, whose book Notes on Nursing: What it is and What it is Not (1859) had helped ready Alcott for her service. Alcott also had some personal experience, having taken care of her sick sister, Elizabeth, whose death from scarlet fever was dramatized in Little Women. “Wonder if I ought not be a nurse, as I seem to have a gift for it,” Louisa wrote in her journal a year later in January 1859, after her mother also fell ill.

In letters home from Georgetown, Alcott recounted gruesome stories of amputations, disease, and despair that nevertheless conveyed both the author’s tenderness and, even more surprisingly, her sense of humor: “I took my first lesson in the art of dressing wounds,” she told them in a letter that appears in Hospital Sketches. “It wasn’t a festive scene, by any means.” Likewise, after telling her readers about the awful hospital food, including bread that tasted like sawdust and rancid-looking meat, she coyly added: “Another peculiarity of these hospital meals was the rapidity with which the edibles vanished.”

Louisa’s family would have encountered in these letters a new style from their daughter and sister, one refreshingly candid and earnest in expression, they encouraged her to publish them. In his journal, Bronson Alcott predicted the Sketches were “likely to be popular, the subject and style of treatment alike commending it to the reader.” They first appeared (with some fictionalization) in the paper Boston Commonwealth, but were eventually gathered together and published as Hospital Sketches (1863). Told from the perspective of a “Nurse Periwinkle,” the stories, much to Alcott’s surprise, were an instant hit. “When I wrote Hospital Sketches by the beds of my soldier boys,” she wrote (in a letter to an aspiring writer), “I had no idea that I was taking the first step toward what is called fame.”

Advertisement

Alcott often expressed bemusement that Hospital Sketches, which she had composed between nursing duties and for no audience other than her family, enjoyed such popularity: “I cannot see why people like a few extracts from topsy turvey letters written on intervened tin kettles, in my pantry, while waiting for gruel to warm or poultices to cool.” Although she was a published author already, Alcott’s first fantasy and adventure tales received nothing like the critical acclaim her nursing stories had attracted. The New York Tribune said of the book, “[Alcott] records her experience in the midst of the saddest scenes which the human eye can witness in a tone of gay, almost rollicking vivacity, which shows wonderful ‘pluck’.” Writing to her publisher, James Redpath, Alcott remarked, “I have the satisfaction of seeing my towns folk buying, reading, laughing & crying over it wherever I go.” She even received a letter from the father of novelist Henry James, who wrote: “I am so delighted with your beautiful papers, and the evidence they afford of your exquisite humanity.”

The sketches exemplified a style that would later characterize Little Women: crisp, light-hearted, yet affecting observations on the mundane scenes of daily life and the emotional ties that form amidst it all. By writing Hospital Sketches, Alcott realized that “I discovered the secret of winning the ear and touching the heart of the public by simply telling the comic and pathetic incidents of life.”

Shortly before joining the Union Hospital, Alcott had been working on another one of her romances. Writing to a friend, she said “don’t be shocked if I send you a paper containing a picture of Indians, pirate wolves, bears, and distressed damsels in a grand tableau.” She had written several such stories under the pen name A.M. Barnard, with titles like “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment” (1862) and “Taming a Tartar” (1867). Though she knew they were not hardly high literature, she could write them quickly and expect decent pay in return, money sorely needed by Alcott and her family.

For much of the 1850s, the Alcotts lived in near destitution, at one point occupying a basement apartment in Boston’s worst slum. Bronson Alcott had proven to be a poor provider for his family. Though he was a man of great ideals (or perhaps because of that very fact), he made ill-advised and impractical investments, at one time starting an agricultural commune despite not having any farming experience. The family only moved into Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts, the idyllic home recreated in Little Women, in 1858, after Ralph Waldo Emerson covered the down payment. The memory of poverty stayed with Louisa, and in spite of the success enjoyed by Hospital Sketches, she had every intention of going back to writing gothic romances and thrillers. In a diary entry from January 1865, she wrote: “I can’t afford to starve on praise when sensation stories are written in half the time and keep the family cosey.”

Alcott only set about writing Little Women at the instigation of an editor in Boston who thought “a girl’s book” might sell well. Louisa grudgingly agreed to try, though she didn’t envision much coming from it: “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters,” she wrote in her diary. And indeed, Alcott would grow resentful of the pressure she felt to marry off all of the March sisters, particularly Jo, who she’d originally envisaged a spinster like herself. Alcott relented though, and Little Women would go on to bring Alcott not only acclaim, but the financial security she had so long sought for her family.

Years after the novel was published, Louisa reflected on her success, again in her diary, citing Hospital Sketches as the pivotal forebear of the novel that would make her famous: “Sketches never made much money, but showed me ‘my style,’ and taking the hint I went where glory waited me.” Alcott was sure to write this arc into the life of her famous heroine as well. In the second part of Little Women, Marmee encourages Jo to write a story “for us, and never mind the rest of the world” (much like the Sketches originated as private letters). To Jo’s surprise, “Something got into that story that went straight to the hearts of those who read it.” For Marmee, there was no mystery as to why: “There is truth in it, Jo—that’s the secret…you have found your style at last.”