The Science Museum is always alive with children. School groups scribble on clipboards, five-year-olds drag parents and grandparents by the hand, push buttons, and make lights flash. Toddlers flag for ice-cream. The halls and galleries ring with noise. By contrast, in the softly lit exhibition space on the second floor, a sudden quiet descends. But almost at once, on entering the museum’s new show, “The Art of Innovation: From Enlightenment to Dark Matter,” here are the children again. In Joseph Wright of Derby’s A Philosopher Giving that Lecture on an Orrery in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun (1766), they lean over, faces lit up, as the girl, her eyes glowing, points over her brother’s shoulder at the tiny planets circling the sun.

That sense of excitement defines the exhibition, as visitors zig-zag from The Lecture on the Orrery through 250 years of art and science. In the book that accompanies the show, far more than a catalog, the curators, Ian Blatchford and Tilly Blyth, lay out their stall. “Throughout history,” they write, “artists and scientists alike have been driven by curiosity and the desire to explore worlds, inner and outer. They have wanted to make sense of what they see around them and feel within them: to observe, record and transform. Sometimes working closely together, they have taken inspiration from each other’s practice.” To illustrate this dual heritage and point to the leaps of imagination in both fields, they have placed twenty works—painting, sculpture, film, photographs, posters, and textiles—alongside the scientific objects that inspired them. Thus A Lecture on the Orrery hangs near James Ferguson’s wooden pulley-operated mechanical model of the solar system, an orrery from the Museum’s collection.

Wright’s painting, so warmly inclusive with its male savants, awed young woman in her hat, and enthralled children, celebrates both the skill of the instrument maker and the rational Newtonian universe. But two years later, Wright painted a complementary picture, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, which shows the precariousness rather than the harmony of natural forces as the bird, deprived of oxygen, flutters near death. This time, the children turn away in fear: in the corner above them, the moon shimmers through a high window, suggesting mysteries beyond comprehension. This painting is not on show here, but the exhibition similarly acknowledges the dangers as well as the delights of scientific advances. In a later section, a large Greenpeace poster shouts, “It’s deadly serious Mr. Reagan—nuclear weapons testing must stop.”

It’s a delicate balance. At the exhibition’s opening, Conrad Shawcross’s sculpture Paradigm (2015) nods to Thomas Kuhn’s notion of the “paradigm shift,” the belief that for ideas to progress, old models and conceptual frameworks must be toppled by the new. The sculpture itself, is a tower of stacked tetrahedra. A small skeletal version of the huge public sculpture outside the new Francis Crick Institute, it seems to defy gravity, rising and twisting while being on the verge of toppling, testing physical laws.

We follow those shifts of thought through the display, which is divided into four sections—although this isn’t altogether clear as you walk round, making some juxtapositions wonderfully startling. It’s odd to move, for example, in the first section, “Sociable Science,” from Wright’s painting of the laws of the universe to a silk skirt and jacket of 1862 dyed with “Perkin’s Mauve Aniline dye.” But the dye, like every exhibit here, has a story behind it: in this case it’s the accidental discovery William Henry Perkin made while trying to synthesize quinine by isolating aniline salts from coal tar. That experiment failed, but he found the dark residue made a purple solution when dissolved in alcohol that would dye silk. When Empress Eugénie and Queen Victoria wore the new color, its popularity soared—though its artificial brightness appalled artists and designers of the Arts and Crafts movement such as C.F.A. Voysey, whose subtle textile, using natural dyes, hangs near the offending dress.

Across the room, the quest for new materials continues, with a wafting terylene dress from 1941, and a screening of the exuberant 1951 Ealing comedy The Man in the White Suit, with Alec Guinness as the naïve inventor of an indestructible textile fleeing from angry industrialists and workers, saved only when his magic material disintegrates around him. There’s a lot of fun, as well as science, in this show—and some joyous artistic accidents, like David Hockney’s encounter with a polaroid camera, which he used for the dazzling grid of Sun on the Pool, Los Angeles (1982). “Drawing with a camera,” he called it.

Advertisement

In the next section, “Human Machines,” the note of fear enters fully with the trauma of mechanized carnage in World War I. A case holds pioneering artificial limbs from the 1920s, and in Otto Dix’s Card Players (1920), three disfigured soldiers sit round a table, their torn limbs and missing jaws replaced by fantastical prosthetics. The destructive technology of warfare and the constructive skill of limb-makers have turned Dix’s men into monsters. Have they, perhaps, become machines themselves?

The complex, sometimes conflictual, relationship of man and machine is a constant thread. Recalling how the mechanical telling of time itself became contested during the Industrial Revolution, as the historian E.P. Thompson described in a famous 1967 Past & Present article, “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,” here is a handsome double-dialled clock from a Macclesfield mill, dating from 1810. In the catalog, the curators tell us that while the lower dial showed the actual time, the upper dial was connected to the silk mill’s waterwheel: if the waterwheel ran slowly, or stopped, “mill time” was slowed or suspended, and the workers would have to make up the lost production time, “ruled by the pace of their machines.” Similarly, a photographic sequence of a woman operating a hand press, using an “old” and “new” method, was taken as part of a British motion study in the 1920s–1930s: the new method, using one stroke less, was said to increase productivity by 40 percent. Nearby, L.S. Lowry’s painting A Manufacturing Town (1922) illustrates his own heartfelt feeling: “I look upon human beings as automatons… because they all think they can do what they want but they can’t. They are not free. No one is.”

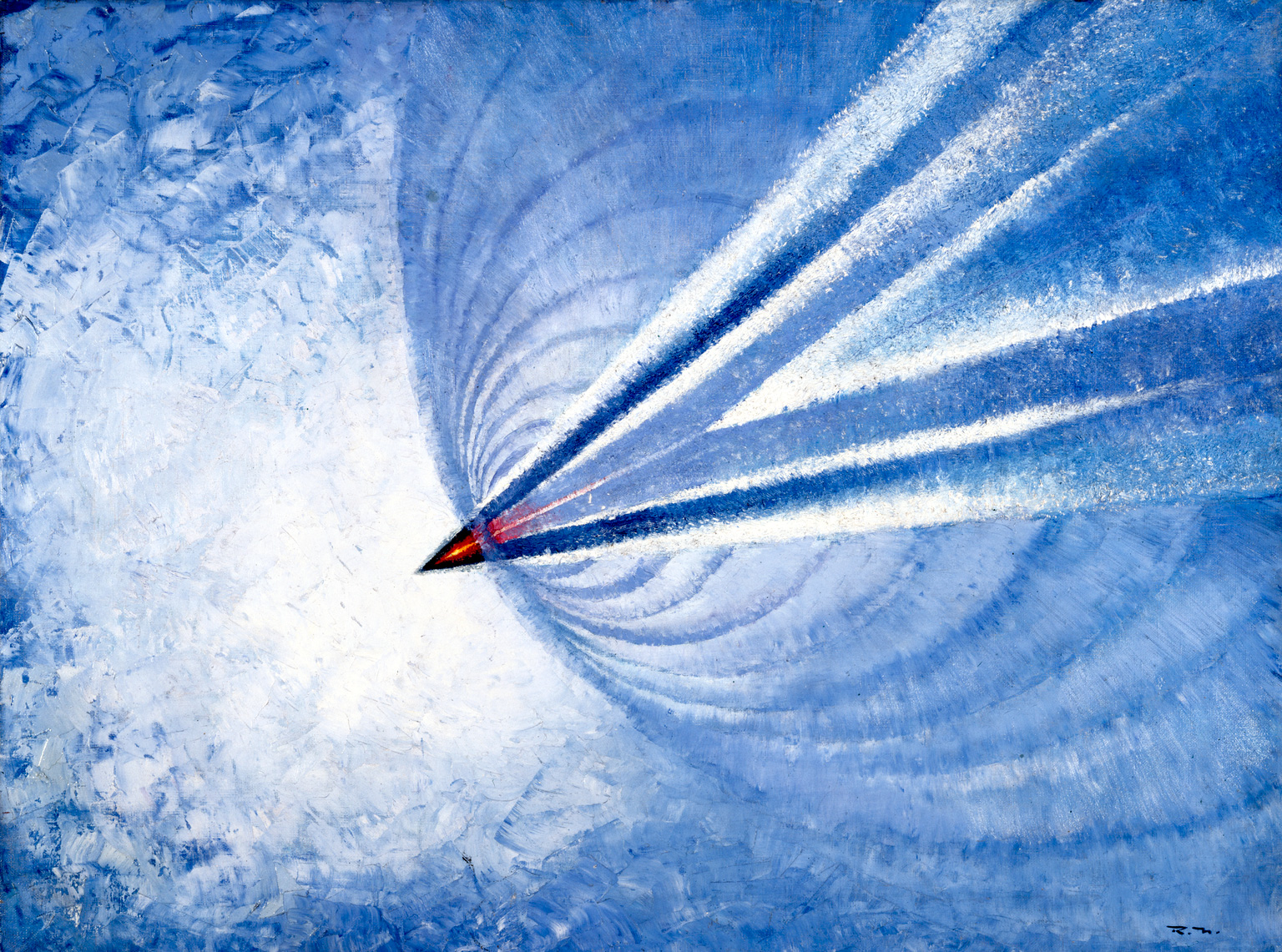

Paradoxically, machines could also make men and women feel free as never before. The flashing lines of Umberto Boccioni’s drawing of a cyclist, The Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913), brilliantly convey the thrill of being at one with a machine, as well as the embrace of the modern that galvanized Italian Futurism. Boccioni’s capturing of motion echoes the earlier photographic experiments of Eadweard Muybridge, and of Étienne-Jules Marey, whose new high-speed shutter enabled him to capture a sequence of actions on a single plate, like the Man doing the high jump, from 1892. The exhibits move us back and forth in time: the excitement of velocity found in Boccioni’s drawing loops back to Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed—the Great Western Railway (1844) hung in a section called “Troubled Horizons,” and forward to the breaking of the sound barrier depicted in Roy Knockold’s near-abstract painting Supersonic (1948–1952), in which a curved line shows how the plane’s speed compresses the air, making shock waves spread and causing a sonic boom as it passes.

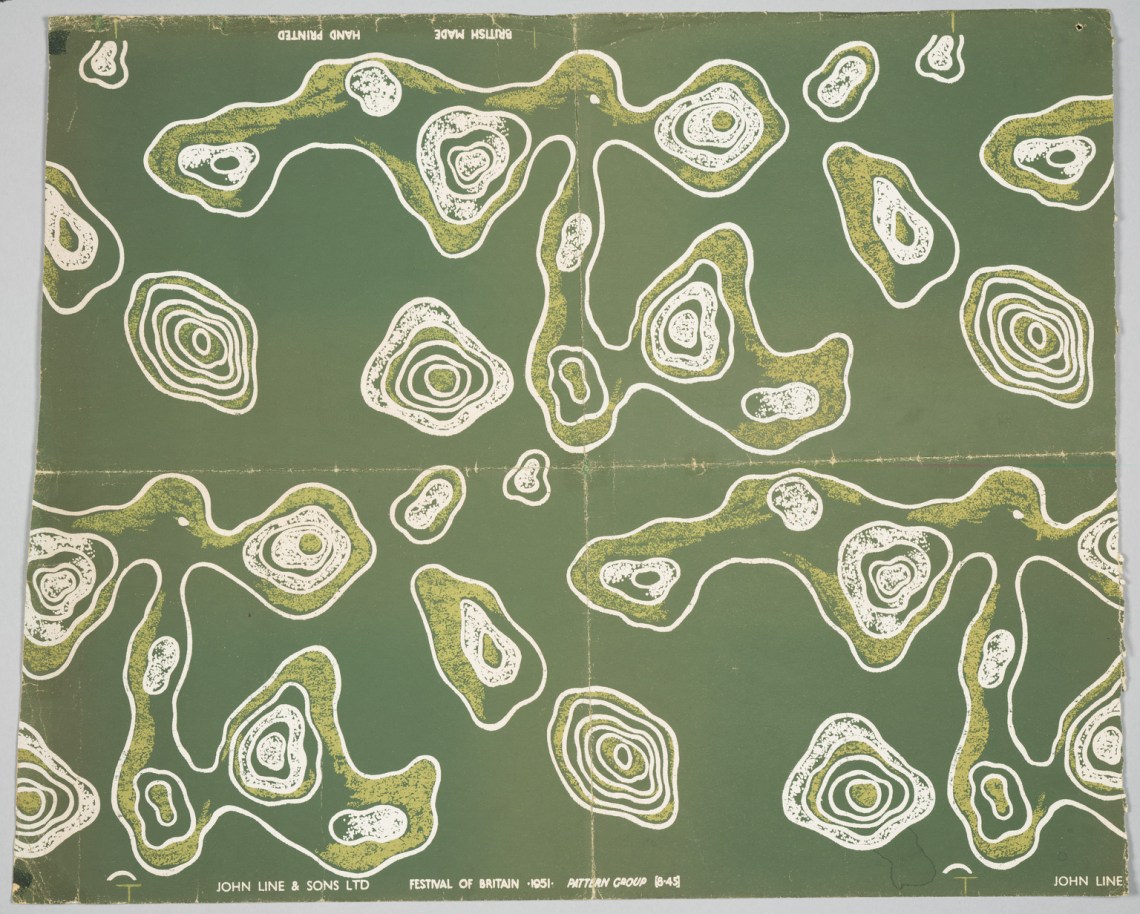

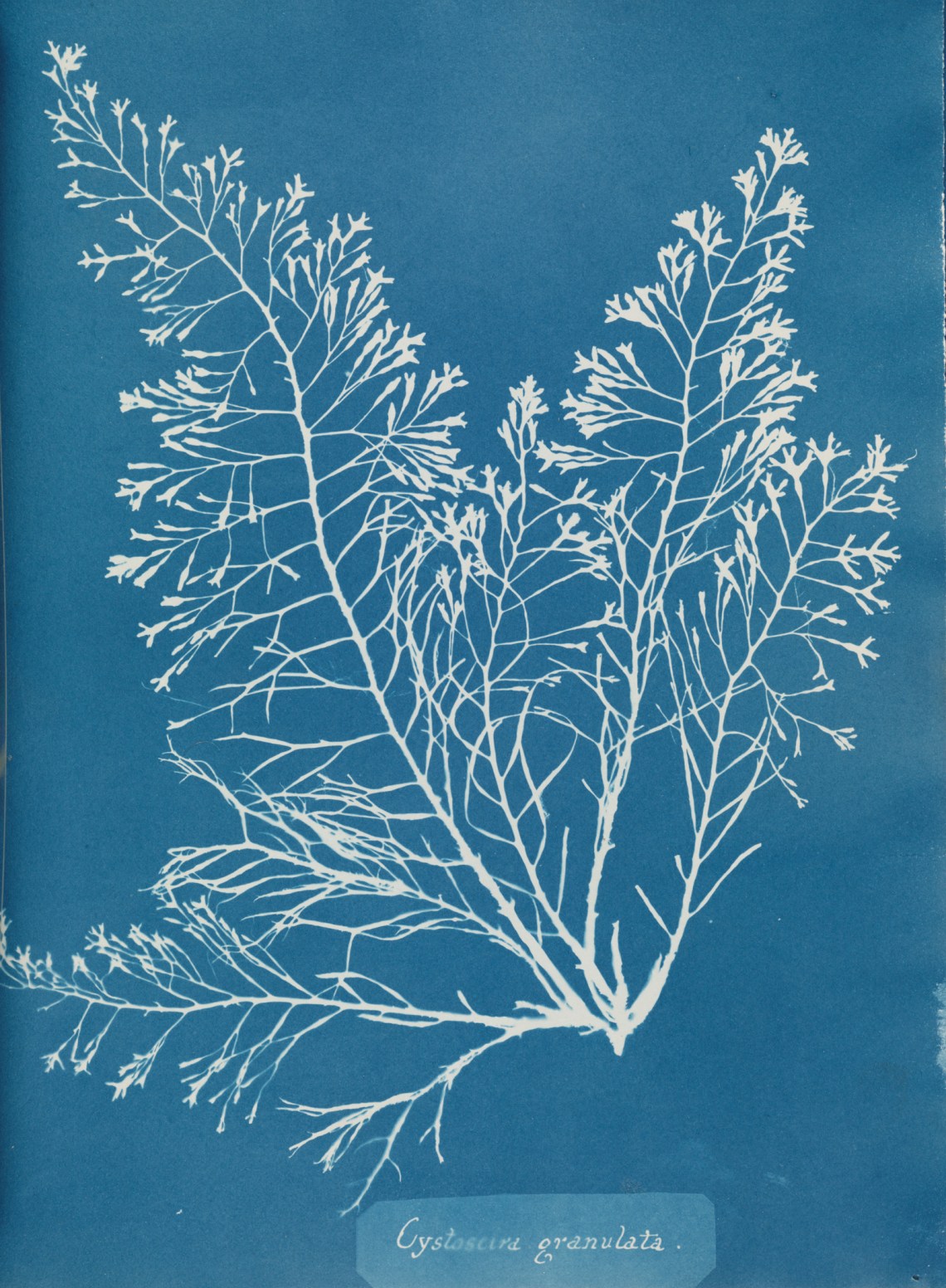

The space devoted to “Meaningful Matter,” turns away from technology to the natural world, explored in Luke Howard’s sketches of clouds in the early 1800s, and in Anna Atkins’s pioneering cyanotypes of algae in 1843. In a later period, natural forms—and the museum’s own mathematical models—also inspired sculptural work like Barbara Hepworth’s Study with Colour and Strings (1939/1961) and Henry Moore’s series of string installations. Less familiar are the textile patterns prompted by atoms and molecules made for the 1951 Festival of Britain. These, used on everything from ashtrays to neck ties, were based on X-ray crystallographic patterns of haemoglobin, while the (rather hideous) olive-green wallpaper for the Festival Hall’s Regatta Restaurant on London’s South Bank drew upon a “contour map,” provided by the crystallographer Helen Megaw, of the inner atoms of the crystalline mineral afwillite (first identified in South Africa in 1925 and named for a De Beers mining official, Alpheus Fuller Williams). How weird to see the optimism of the atomic age as décor.

And so we conclude with Einstein. Here is a gyroscope from Gravity Probe B—its spheres the most perfectly precise ever made, for a 2004–2005 experiment to test the general theory of relativity’s prediction that a huge body like the Earth would warp and twist surrounding fabric of space-time; the results, announced in 2011, proved Einstein right. Here, too, are Cornelia Parker’s Einstein’s Abstracts (1999), super-magnified images of the chalk marks on a blackboard that Einstein used in a lecture in Oxford in 1931. They look mysteriously like photographs of space. On the wall above are Einstein’s words: “I am enough of an artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited, whereas imagination encircles the world.”

Advertisement

“The Art of Innovation: From Enlightenment to Dark Matter” is on view at the Science Museum through January 26, 2020.