It wasn’t until Luchita Hurtado was ninety-nine years old that she would witness the opening of her first museum retrospective. Titled “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn,” the exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) showcases the artist’s paintings, drawings, and sketches spanning eighty years. Inside the galleries in early February, she addressed the press, smiling, “This is one of the best moments of my life.”

Hurtado spent much of her life mingling with and befriending some of the twentieth century’s best-known artists. She was close to Isamu Noguchi and once attended a party in Frida Kahlo’s hospital room. When she first met Marcel Duchamp, he gave Hurtado a foot massage. Jackson Pollock “scared the hell” out of her. But none of them knew Hurtado herself was an artist.

There was never a time when Hurtado wasn’t making art, but for years, she hid her art, turning her canvases to the wall when she had visitors. As she told The New York Times, “I always felt shy of it. I didn’t feel comfortable with people looking at my work,” adding that “there was a time when women really didn’t show their work.”

Hurtado kept her proclivities a secret ever since she was a teenager. After moving with her mother and siblings from Venezuela to New York City at the age of eight, Hurtado decided to study art in high school. But she did so against the will of her mother, who thought Hurtado was studying fashion design—and did not learn of her daughter’s aspirations as an artist until graduation day. “I felt it was my right to decide who I would be,” Hurtado reflected, eighty or so years later, at a public talk with LACMA curator Jennifer King and Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator at London’s Serpentine Galleries, where the Hurtado exhibition was first shown.

Lacking encouragement and a community to nurture her development, Hurtado continued to work privately and secretly. Two years after graduating high school, in 1938, she was married, and by the early 1940s, she had two children. Still, she managed to work into the night while her children were asleep. Making art “was a need,” she’s said, “like brushing your teeth.”

But this isolated existence also gave her a sense of independence and allowed her to create a startlingly original and prolific body of work. Reflecting back on her life today, she often refers to this idea that she went her own way. At the kitchen table, she made crayon drawings of dancing, totem-like figures and invented a technique by which she’d spill dark ink that resisted the waxy crayon surface and pooled into the paper gaps. She called these “resist” drawings—a title and technique that feel only apt for someone who’s acknowledged her own “built-in resistance” to “the commercial world.”

The marriage did not last long, and in 1947, Hurtado married the artist Wolfgang Paalen, moving her family to Mexico City, where he lived. There, she met and befriended many Surrealist artists, but even then—in a new city, with a new husband, and among new friends—she continued to keep her own production hidden. Paalen knew about Hurtado’s work, though she says he was not particularly interested in it. He did reserve a corner of his studio for her, where she turned her drawings the other way when she was done.

In 1949, after suffering the trauma of losing one of her children to polio, Hurtado moved to California with Paalen. She longed for another child, but Paalen did not want one, so the couple parted ways. Hurtado eventually settled in Santa Monica with her third and final husband, the artist Lee Mullican, with whom she had two more children. Since then, Los Angeles has been her home.

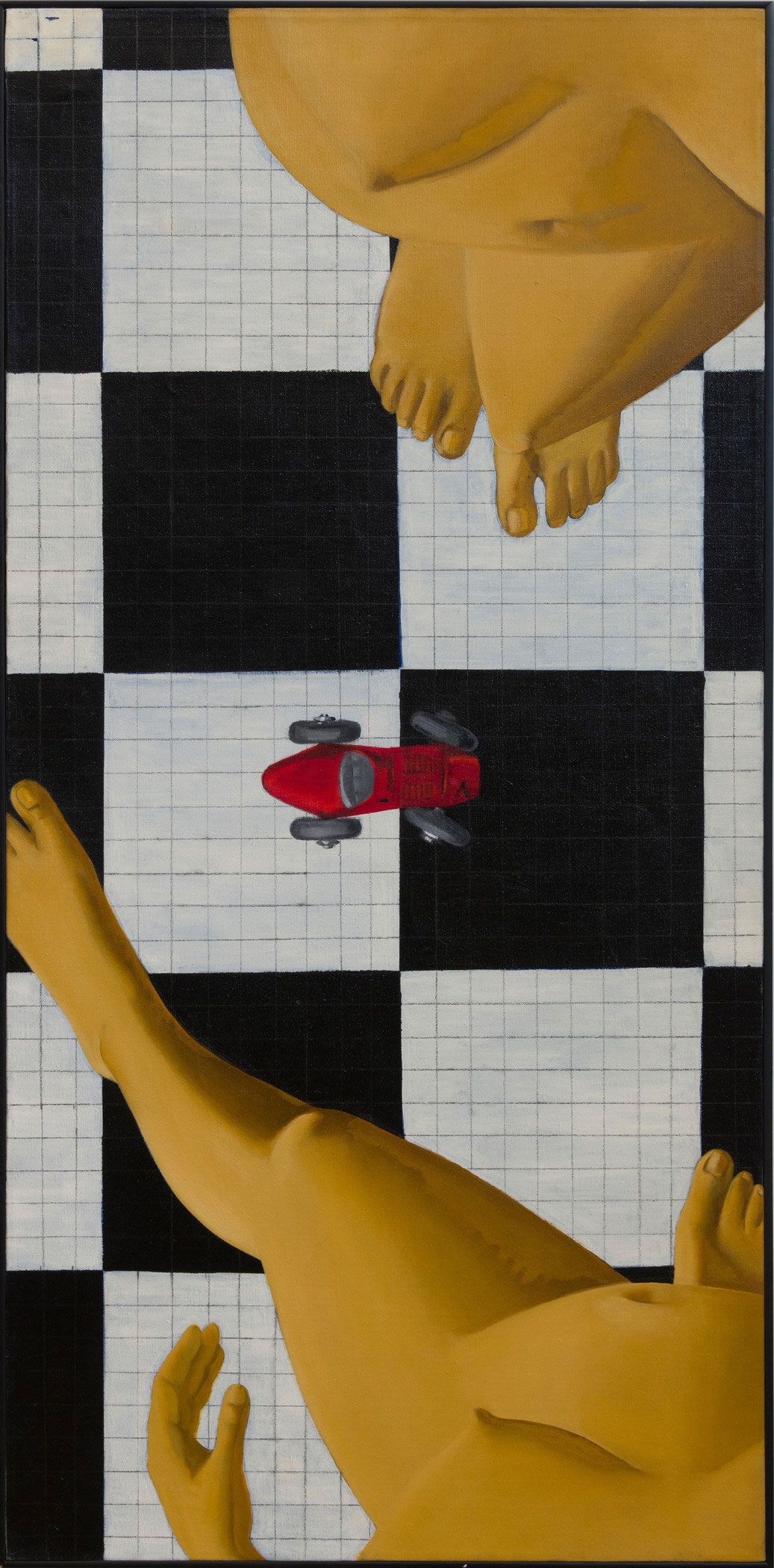

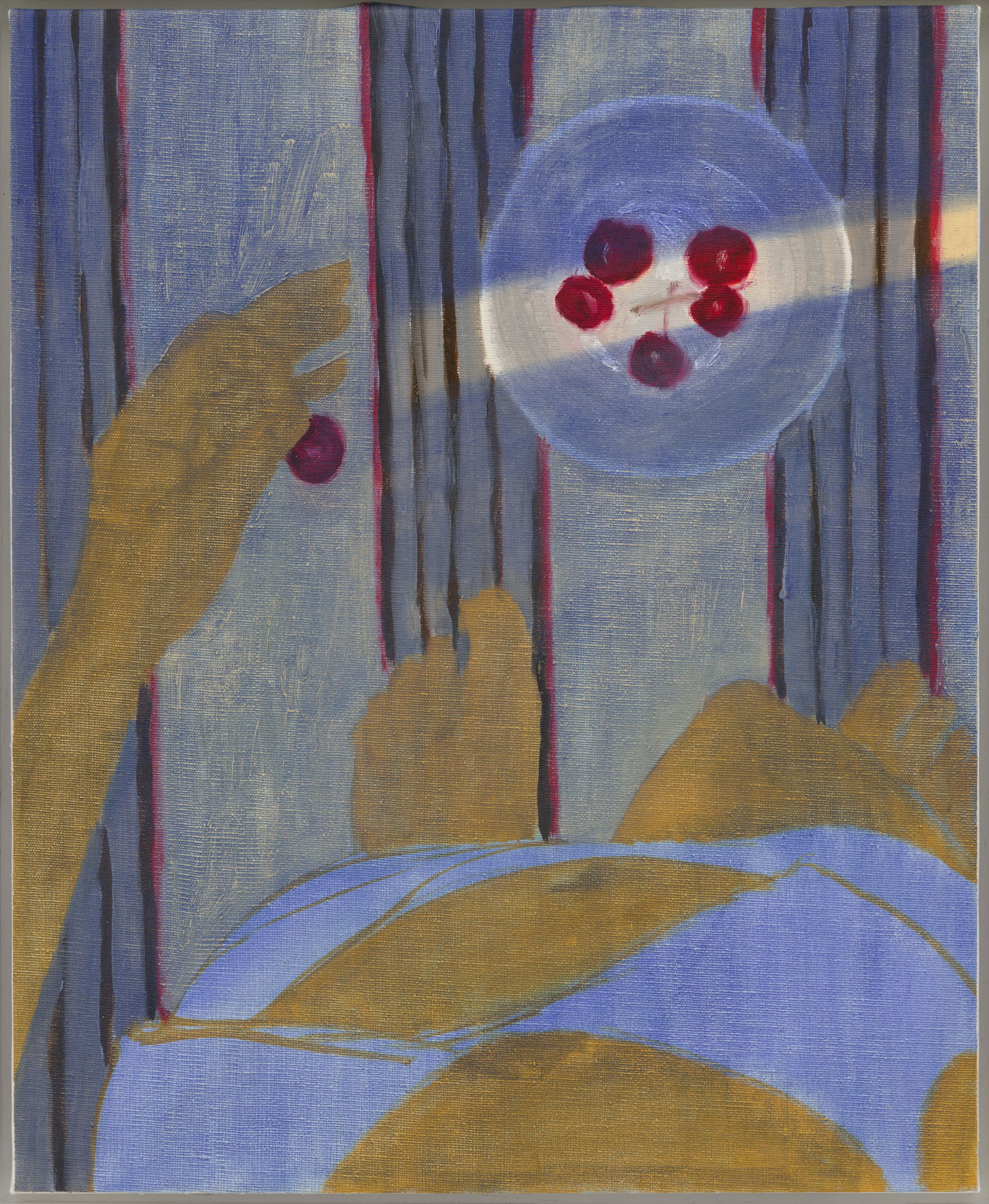

It was in Santa Monica that Hurtado, at the age of forty, got her first studio (Mullican was also aware of his wife’s work, though Hurtado says she was still private about it). At long last, with a room of her own, she began painting self-portraits that are, I think, her most powerful works—the ones in which she found her voice. They show the perspective of her looking down at her body, mostly naked or in underwear. As viewers, we’re forced to look from her perspective, to embody it, as we dodge her children’s toy cars left behind on the floor. For someone who hid her work, the paintings are surprisingly generous, open, and curious, but also assertive in their direct and intimate viewpoint. They teach, perhaps even demand us, to look with empathy.

Advertisement

In 1968, she relocated with her family to Chile for a year—being married to a successful artist required traveling for Mullican’s exhibitions and sometimes moving for his job opportunities. Without a studio, Hurtado worked inside a closet—a far cry from her own room with windows—where she continued to make this series of portraits. But their mood darkens and adapts to their environs; in some, she is ghostly or faintly visible, and in others, you can see a shaft of light coming from the partially opened door.

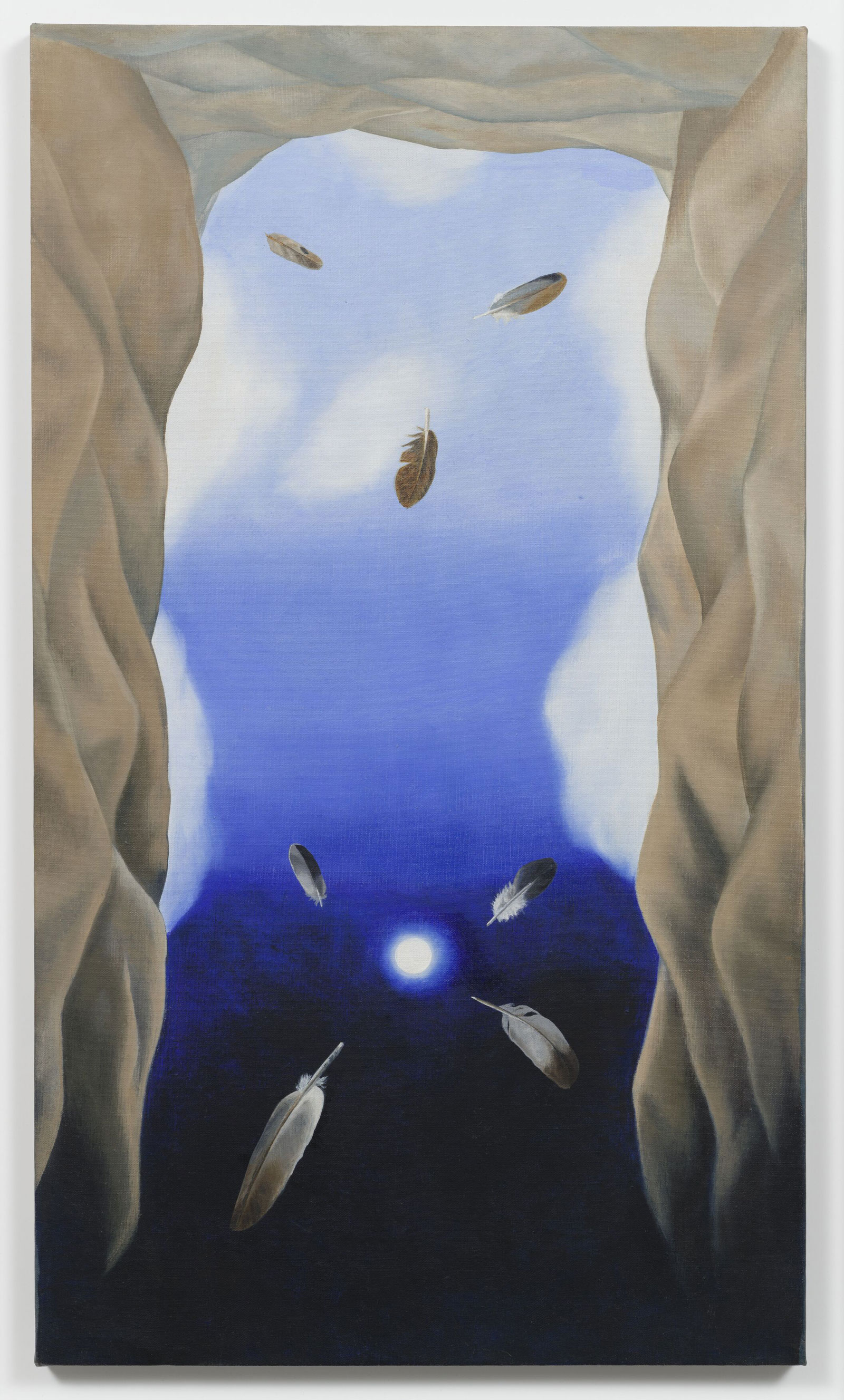

When the family returned to Santa Monica, something shifted in Hurtado. Now that her children were older, she had more time. She took up a one-month artist’s residency in New Mexico. Inspired by the landscapes of Taos, she made paintings of desert hills that look like breathing bodies; she called these Sky Skins. In these works, she continued to direct the viewer’s gaze through her own. In one painting, she lets us view the sky as if we were laying on our backs, the moon a glowing circle, like a belly button in the night sky. She named it, “The Umbilical Cord of the Earth is the Moon.” After years of painting her downward gaze in the domestic indoors, her eye moved outward and upward.

Some have connected these works to the Surrealist school, but Hurtado resists this interpretation. In an interview with Obrist, she says her work has always been “more intuitive” than theirs, which she calls “calculated, intellectualized.” While her art is certainly dreamy, it does not seek to transport us to an otherworldly or subconscious place, but rather offers a clear-eyed vision of what she sees. Like the self-portraits, the Sky Skins are eager to communicate—to give us a directive in how to look at the world.

Not long after her residency and starting the Sky Skins, Hurtado finally found her audience and began her foray into the art world. In 1971 she attended a meeting of women artists organized by her friend Joyce Kozloff. In a story Hurtado likes to repeat, she introduced herself as Luchita Mullican, only to hear a voice across the room say, “Luchita what?”—prompting her to respond, in a moment of revelation, “Luchita Hurtado!” Together, these women organized the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists and issued a report on the underrepresentation of women in Los Angeles museums, including LACMA.

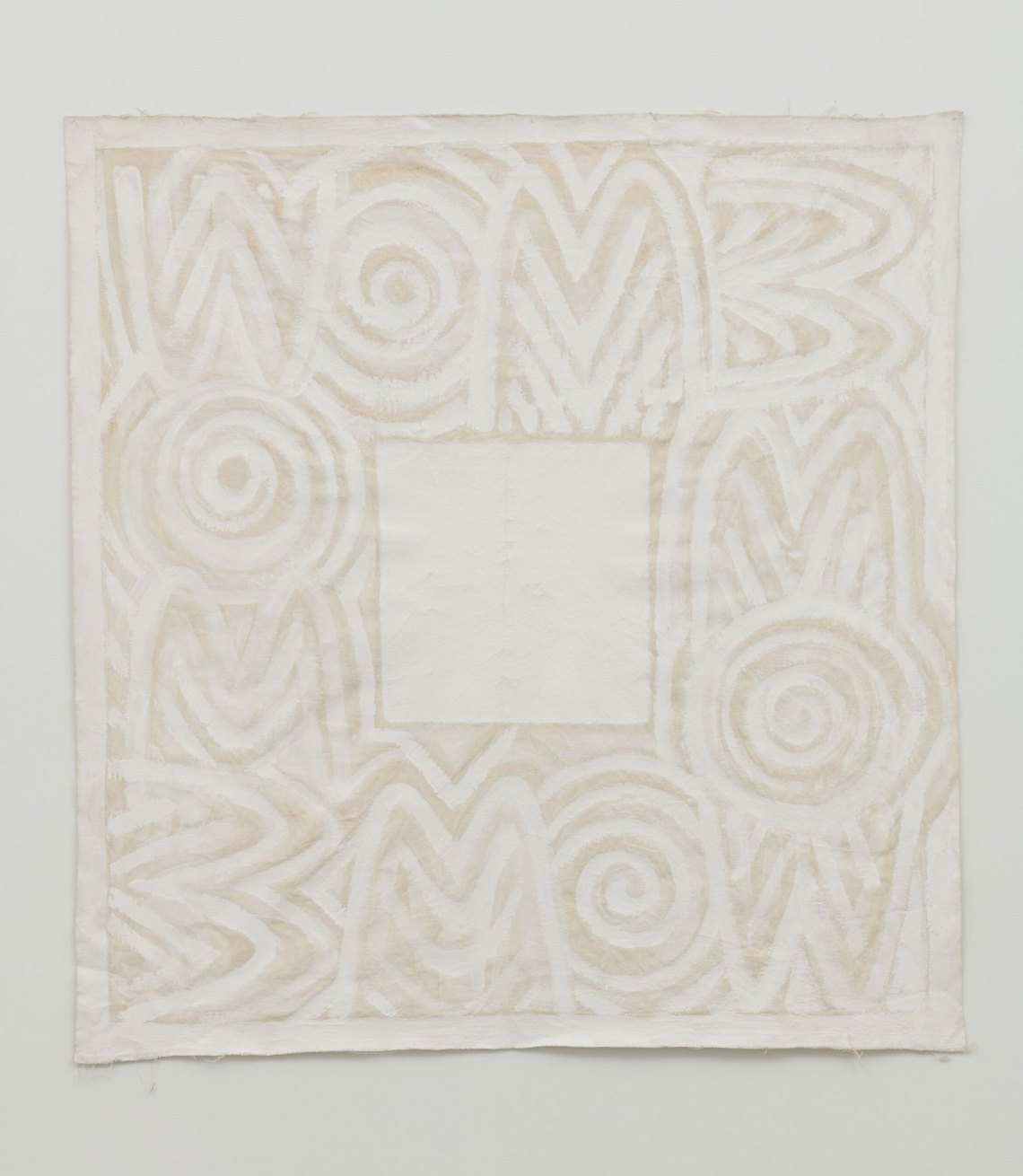

This encounter would radically change Hurtado’s own relationship to her work. Since then, she said, “I have never again faced my paintings to the wall. Quite on the contrary, I am quick to show them.” Just a few years later, in 1974, she had her first solo show, at the Woman’s Building, in which she exhibited paintings that look like abstract patterns but are actually shaped by words, like “I am.” She continued to make work along these lines; in some, you can’t make out what they say, while others are spelled in clear, all-capital letters: “SOY” and “WOMB”—words that seem to voice what her previous paintings were about. Hurtado has also called these word paintings self-portraits, but instead of inviting us to look through her perspective, they confront us in loud, unmistakable terms.

Although Hurtado was ready to show her work by the 1970s, it was nearly fifty years before the art world finally took notice. In 2015, the director of the Lee Mullican’s estate, Ryan Good, came across 1,200 artworks in Mullican’s files with the initials “LH.” Good was astonished when Hurtado identified them as her own (she thought these works had been lost), and he helped set in motion the series of shows that led at last to the institutional recognition Hurtado enjoys today. “Now that they’ve discovered me again—I live again,” Hurtado said in 2018.

That she uses the term “again” suggests that a first moment of discovery took place in that room of women in Los Angeles. Hurtado’s story recalls the stories of many other women “discovered” in old age—like Zilia Sánchez, Carol Rama, and Etel Adnan—who exhibited abroad or in smaller circles, and were studied by a few dedicated scholars, but only received wider recognition after major American museums took notice and showed their work.

To some, Hurtado’s story might seem to belong to another time. But on the same week that I saw her show, I heard echoes of her story in the words of three contemporary artists in Los Angeles. Andrea Fraser, Shinique Smith, and Liza Lou had been invited by the Creative Artists Agency and Anonymous Was a Woman organization to talk about women making art. They shared the “pain, shame, and disappointment” (in Fraser’s words) of trying to make a career in an art world that has historically undervalued women. Smith said it took years before she could give herself the “permission to be an artist.” Lou added that this feeling of “being on the outside” has nonetheless pushed her to “find and sustain meaning” for herself, alone, in the studio. Fraser concluded that, as a woman, one must “carve a place for oneself” and establish one’s own set of “criteria” when making art.

Advertisement

Because of this, arguably the work of women artists has often been more independently minded, different from what has been accepted or deemed valuable by institutions. Even ten years ago, Hurtado’s work might have been thought too “female”—nude self-portraits, images of giving birth, and canvases emblazoned with words like “womb.”

At the LACMA talk, I was curious whether Hurtado took issue with being identified and discussed as a “woman artist,” as some artists have, and asked her during the Q&A whether she identified as one. She didn’t answer yes or no, but instead began sharing memories of the Woman’s Building. “For the first time you had women talking together about art,” she said. “For the first time I realized I wasn’t Luchita Mullican as an artist. I was Luchita Hurtado.”

In a way, her indirect answer points to how difficult this question has been for women who are artists. But it also suggests that while some of us may not like the term “woman artist”—“excellence has no sex,” as Eve Hesse once said—the phrase can still feel relevant, even necessary. For Hurtado—like Fraser, Smith, and Lou—identifying as a woman has proven to be an obstacle but also a source of insight and even artistic liberation. Working in seclusion, in a sense, allowed Hurtado to create art unencumbered. Just as important, perhaps more so, the Woman’s Building banded together as women artists to find a way forward together.

Today, as witnessed at the LACMA exhibition, people become giddy around Hurtado’s work, making it all the more disappointing that the exhibition, like many others, had to close early due to Covid-19. For now, we can hold out hope that, conditions allowing, “I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn” will travel as planned to the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City this fall, when Hurtado will celebrate her one-hundredth birthday.

“Luchita Hurtado: I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn” opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on February 16, and is now temporarily closed with the possibility of extension; visit LACMA’s website for updates.