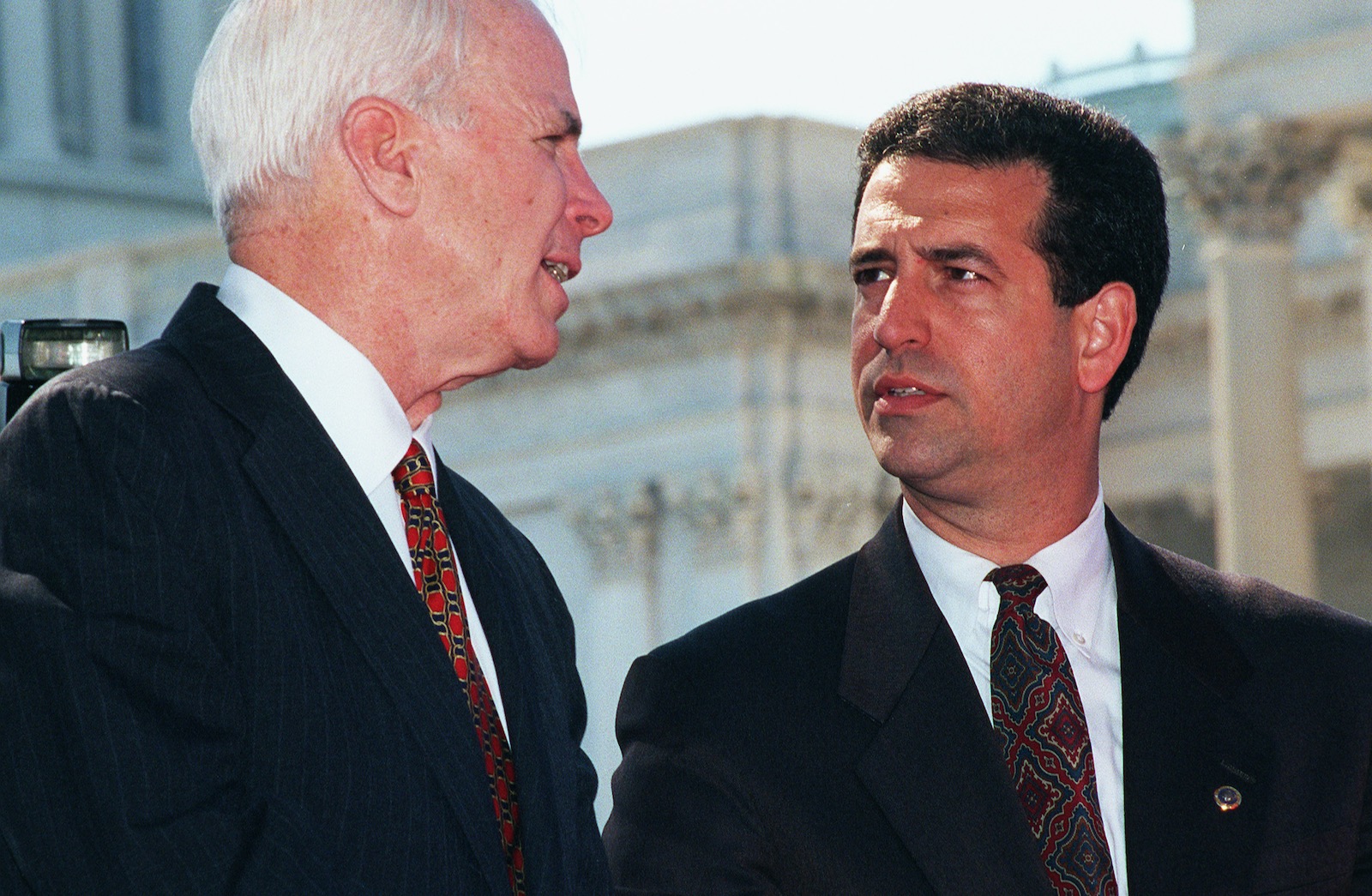

Throughout the three terms he served in the US Senate—from 1993 to 2011—Russ Feingold was seen as a progressive who could successfully make common cause with conservative legislators. After the Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act, curbing the role of big money in elections, was passed in 2002, this brainchild of the Wisconsin Democrat and the late Arizona Republican John McCain became known by their names as McCain–Feingold.

But he also had respect as an independent voice who would vote according to his conscience. His was, for instance, the lone senatorial “nay” on the 2001 USA Patriot Act, which permitted warrantless searches and, some held, unconstitutional surveillance of US citizens.

In 2010, in a sign of wider political changes in Wisconsin, once home to “Fighting Bob” La Follette, Feingold’s Senate career came to a sudden end when he was defeated by a wealthy Tea Party Republican, Ron Johnson. In the years that followed, Feingold toured the country giving speeches, accepted posts as a visiting professor, and became, for a time, President Obama’s special envoy to the Great Lakes region of Africa. He ran again for the Senate in 2016, but it was a bad year, in general, for Democrats.

Now, aged sixty-seven, he has found a new métier. Since March, he has been president of the American Constitution Society, an organization of lawyers that aims to be a liberal counterweight to the legal juggernaut that is the conservative Federalist Society.

“I see this as a chance to get in there to work with these wonderful progressive lawyers to try to undo what has been so devastatingly demonstrated in the past few years,” he told me in the first of two Zoom interviews conducted in late June. What follows is an edited and condensed version of the conversations.

Claudia Dreifus: How did you come to your new job?

Russ Feingold: By that magical instrument known as voicemail. [Laughs] I had just finished teaching a class—I was a visiting professor at Harvard Law School—and there was a message on my cell phone from someone who identified herself as a headhunter. “Mr. Feingold, we hope this is your voicemail,” she said, “because we represent a nonprofit that’s looking for a CEO.”

I immediately thought, “Odds are it’s going to be something I wouldn’t want to do.” That’s because a few months earlier, a headhunter had contacted me about a firm wanting me to be their front at one of those vaping manufacturers.

Do ex-senators often get solicitations of this nature?

It happens. Apparently, the more principled you were while you were in Congress, the more they are willing to pay afterward. I’ve always felt that once you’ve been in the Senate, you shouldn’t allow people to take advantage of the fact that you were a senator to advance causes you don’t believe in.

But when this second headhunter explained that the client was the American Constitution Society, I was actually interested. Over the years, I’d appeared at ACS events at the various law schools and I’d always had a positive impression.

What is the ACS’s mission?

That the legal system must be fair for everyone and all Americans deserve to be heard.

ACS has over two hundred law student chapters and fifty lawyer chapters—with a membership that believes that the federal judiciary must be seen as legitimate. We think it important that the courts not be purely ideologically driven. This is particularly important in the area of racial justice. In this way, ACS is an extension of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The civil rights movement is a great symbol of the attempt to make the words of our Constitution live up to reality.

Today, the system is not on the level because groups like the Federalist Society have distorted how some in the judiciary interpret the Constitution.

For those not familiar with it, what is the Federalist Society?

It’s an extremely well-funded network backed by the Mercers, the Kochs, the Scaifes, and others—the conservative dark money crowd. Their stated goal is to take the Constitution back to the pre-New Deal era, a time when the Constitution did not protect women, people of color, LGBTQ individuals, consumers, workers, or criminal defendants. The Federalist Society espouses a method of constitutional interpretation their leaders call “originalism,” but only follow it when it suits their political goals.

I’ve been to a number of Federalist Society events and they’re very professional. There’s almost a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde quality to what they do. The dark side of the organization is that it serves as a backdoor for highly ideological young conservatives to become federal judges. The leadership identifies ambitious law students from its campus chapters, mentors them, and puts them on track for judicial clerkships—if they are willing to accept a certain conservative litmus test.

Advertisement

Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch came out of the Federalist Society. Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas are members. Most of the two hundred federal judges that [Senate majority leader] Mitch McConnell has pushed through the Senate have the Federalist Society stamp. McConnell has gotten more than fifty federal appeals court judges confirmed and the vast majority of them come from the Federalist Society list. These are lifetime appointments and they are almost all quite young.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump told the Federalist Society leaders, in effect, “Give me your list.” They did, and he’s stuck to it.

Do you see the ACS, under your leadership, mirroring that strategy—though from a different direction?

I would say the opposite. Instead of mirroring their approach, we are pivoting.

What’s their approach?

They tell a president who doesn’t know anything about courts or judges, “Hand us your power to decide who the justices will be and we’ll take care of it.” Trump’s been happy to do that.

That’s how the constitutional obligation of the president to nominate judges, and the Senate’s to “advise and consent,” was essentially handed over to an organization with a very narrow view of the law and a very specific agenda on guns, abortion, and corporate profits. That’s their litmus test for a nomination.

At ACS, we don’t have the Federalist Society’s unlimited resources or its backroom access to power, but we do have a lot of smart local lawyers who know their communities. Our approach is a grassroots approach. We have forty working groups across the country ready to propose judges based on their record of service to their communities. We’re going to be ready with vetted names. We’ll be suggesting candidates who are ethnically and racially diverse and diverse in the kind of practice they do. Our list might include public defenders, local advocates, not just people who’ve already been judges.

Do you, at this moment, have candidates ready?

I don’t, but these groups are meeting, and if there is a change in the White House, they will be ready to present names to a transition team. We’ll have a list. Other groups will, too. We don’t expect ours to be the only list, and we welcome that.

I’ve read that because of how Neil Gorsuch ascended to the Supreme Court, you consider the current high court “illegitimate.” That’s a harsh assessment. Can you explain how you came to it?

It’s not that I think that Neil Gorsuch isn’t otherwise qualified to be a justice, but his seat was obtained illegitimately.

After Justice Scalia died in February of 2016, President Obama still had almost a year left to his term. So that Supreme Court seat was rightfully his to fill. But Mitch McConnell refused to hold any hearings on Obama’s nominee, Judge Merrick Garland. The seat was held vacant till Trump took office and could appoint the Federalist Society candidate, Neil Gorsuch.

This was an absurd denial of a president’s constitutional right to have his nomination considered by the Senate. It was not Donald Trump’s to fill. This was a theft of the Supreme Court. The right stole the Supreme Court. They stole it.

I’ve just read Carl Hulse’s book Confirmation Bias, and he clearly documents what happened. When Justice Scalia died, one of the first persons to be told about his death, before it was even public, was Leonard Leo, the strategic guy for the Federalist Society. It was Leo who told Mitch McConnell about Scalia’s death.

Can you imagine that the majority leader of the Senate finds out from some guy representing an outside interest group? He doesn’t find out directly from the court or the family. That is how powerful they have become.

But Gorsuch did get confirmed. What do you do about that now?

This is where, somehow, progressives and others have to develop a strategy where there will be some payment, reparations if you will, to make up for the theft.

One idea, I’ve heard: if the Democrats get the Senate back in November, they could negotiate a compensatory deal with Republicans. Maybe there could be an agreement with regard to the next two or three Supreme Court Justices allowing for this theft to be undone.

Granted, this would be hard to do. It would probably have to be done through a change in the Senate rules.

Advertisement

Even without a deal, Supreme Court nominations are likely to become an issue in the near future. I can see the Supreme Court changing very quickly. I think there are going to be more vacancies than people realize and not only on the progressive side. One hears talk about some of the conservative justices not wanting to continue.

What’s your opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts?

I voted for him. I got a lot of flak for that.

When you’re on the Judiciary Committee as I was, you get to meet the prospective justices individually. When Roberts came to see me, I was really impressed with his intelligence and understanding of the law. I thought, “George Bush is going to get to fill this seat, one way or another. Are we going do any better than this?” And I thought, “Probably not.”

Your instinct has, to a degree, been borne out. In recent decisions—on abortion rights, the Affordable Care Act, lesbian and gay rights, and DACA—it was Roberts who voted to an extent with the liberals. On many matters, he’s become the surprising swing vote.

Well, Roberts is very conservative, but he’s not as ideologically locked up as Alito and Thomas. Moreover, I think Roberts is always watching what the American people think about the Supreme Court. I think he cares that the Roberts Court is not perceived as entirely partisan.

Of course, this does not excuse his harsh rulings on voting rights, reapportionment, and corporate governance, but he has prevented the court from becoming entirely partisan.

The chief justice presided over the Citizens United decision, which dealt a blow to your signature accomplishment in the Senate, the Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act. Your law curbed the role of big money in election campaigns. You must have been hugely disappointed…

I was. However, there is a widely held misunderstanding that the decision overturned the primary provision of McCain–Feingold. What remains, despite Citizens United, is the ban on soft money in campaigns.

What the court actually did was overturn a 1907 law, the Tillman Act, that Teddy Roosevelt signed. In doing so, the court decided that corporations were like individuals and had free speech rights, permitting them to spend unlimited amounts in campaigns. Of course, the decision was extremely damaging to efforts to get big money out of politics, but important parts of our original law still stand. And I’m grateful for that.

In liberal legal circles one hears, these days, of proposals to restructure the federal courts, especially the Supreme Court. There’s talk of trying to end lifetime appointments. One also hears of proposals to change the number of justices on the Supreme Court. What’s your view on these ideas?

I think there needs to be a real national conversation about judicial tenure.

Should it be nine justices? After all, it hasn’t always been nine. Should there be a term limit of eighteen years? Should there be rotating nominations? I had a law student recently who wrote a paper suggesting that every incoming president should automatically get two picks for the high court. You’re right: these sorts of proposals are very much in the air.

Aren’t they a little reminiscent of FDR’s ill-fated plan to expand the number of justices on the Supreme Court—“court packing”?

Funny that you should mention that. While I was still in the Senate, I visited Hyde Park. That’s where the FDR library is. I said something to my guide for the day, Katrina vanden Heuvel [publisher of The Nation], about Roosevelt’s “court-packing plan,” and she harrumphed and said, “Here in Hyde Park, we refer to that as the ‘court-reform plan.”

I got a kick out of that because at the time I was still in the mindset that this wouldn’t be right. In the interim, a lot of distinguished scholars have pointed out that essentially what the right has done is court packing. They don’t fill open seats until a Republican comes in. Then they deliberately pick people who are very young and who will serve for decades to come. They’ve been manipulating this.

I understand they may even be trying to manipulate another Supreme Court justice between now and November—so that they can control the court for the next forty to fifty years.

Do you, like many, follow the state of Justice Ginsburg’s health with obsessive interest?

Well, that feels like it’s an invasion of her privacy. To me, her situation raises the question of whether it’s a good idea to have anyone serve on the court for life.

Now, I am eternally grateful to Justice Ginsburg. Maybe she wants to stay on for ten more years and I sure hope she does. But there’s something untoward about there being an almost unnatural amount of pressure for her to stay on.

This is a discussion that ACS will promote, without taking a specific position, but I think that conversation is growing.

If the Democrats do take the Senate in November, what’s on your wishlist?

I’d like to see that whoever controls the Congress will end federal executions. There’s a lot of momentum for ending it. It used to be that just Wisconsin and Michigan didn’t have the death penalty. Today, twenty-two states don’t. Every year, more and more people oppose it.

In 2000, while I was still in the Senate, I proposed that as we begin the new millennium by eliminating federal executions. Things were moving in that direction. Then 9/11 happened. That was the end of it. But people are again speaking loudly about abolition.

Horribly, the Justice Department under Bill Barr has insisted on doing some executions. There hasn’t been a federal one since 2003. They’re scheduling some for this summer.* They have cynically picked out four federal prisoners who, I believe, are all white and they’ve done this purposely to try to suggest that the death penalty isn’t racially biased, which it is.

At the American Constitution Society, I want this to be one of our leading issues. Abolishing the death penalty ties us to the enormous issue of racial justice. As we know, a disproportionate number of those who are executed are African-American.

This issue is also a good way to take on the Federalist Society and the originalists. Their position is that the death penalty is constitutional because the Founders didn’t specifically exclude it. So that’s where the originalists don’t play straight and engage in what I call “convenientism.”

They claim this because the Founders did write “there shall be no cruel and unusual punishment.” But did the Founders make a list of what they defined as that? No! They intentionally left the language vague—I think, to let every subsequent generation ask, “What in our time, do we consider cruel and unusual punishment?”

You mentioned Attorney General William Barr. When he was nominated, many in legal community were relieved. They thought, “Phew. Barr is of the system and he believes in it. He’s one of us.” Did that turn out to be true?

Absolutely not. As you know, Barr had been the attorney general in the George H.W. Bush administration, so nobody thought he was some kind of madman who would go along with every ridiculous claim that Trump came up with. As Trump’s attorney general, he’s allowed interference in sentencing proposals by prosecutors; he’s shown himself to be somebody who doesn’t believe in the inspector general system, somebody who recklessly starts reinitiating the death penalty for political reasons.

I never imagined that he would be unable or unwilling to stand up to obvious attacks on the Constitution or the rule of law. There are many conservatives for whom I have great respect. They know how to draw the line. I don’t know what has happened to Barr and why this motivates him, but it is, actually, inexplicable. And extremely angering.

In 1974, after Richard Nixon was driven from office, many observers opined that Watergate proved the strength of the American system. Has Trump uncovered something we hadn’t previously suspected—the system’s astonishing vulnerability?

Yes, I am shocked at how vulnerable the system proved to be. I always believed that the system was fundamentally solid, that those in power knew the limits and the norms. But then, I couldn’t imagine the American people voting in someone who appeared to have no understanding of our system and appeared not even to respect it. It turns out that if we were foolish enough to elect somebody with a complete disregard for our legal system, very bad things can happen.

And they’ve been happening, in part, because presidential power has increased way beyond what the Founders intended. The Democrats share responsibility with the Republicans for that. Over the years, they’ve participated in allowing presidents to intervene in foreign conflicts without votes by Congress. With the Republicans, they did not challenge the growing role of big money in politics. Instead, they often embraced it.

So I believe the Constitution has been damaged on a bipartisan basis. Both parties allowed the executive branch to grow in power. An imperial chief executive: that’s not our system. Our system is supposed to be governed by checks and balances.

You mentioned being approached with an offer to work as a lobbyist. Is it a problem for former senators: figuring out how to make a living after leaving office?

It’s a very serious problem.

I was amused recently when Trent Lott was being criticized for all the lobbying he’s done. He said, “What do you want me to do, become a heart surgeon?” [Laughs] But seriously, when you devote, as I did, twenty-eight years to public service and you’re not independently wealthy, you have to do something.

When I was defeated for Senate in 2010, I promised myself to never become one of those senators who joins the revolving door and becomes a corporate lobbyist. I couldn’t do it. I always thought of what my dad, a lawyer in Janesville, Wisconsin, had taught me: all you’ve got is your integrity.

Does that connect with what brought you into politics in the first place?

I’ve always been absolutely fascinated by it. When I was five, I announced I was going to become the first Jewish president. As a kid, I was absolutely enamored with John F. Kennedy. When Kennedy won the 1960 election, that was it: I wanted to go into politics.

From time to time, my father tried to dissuade me. He didn’t like the idea of actually running for office. In fact, when I was graduating from Harvard Law School, he implored me to try to do judicial clerkships or to spend a few years at a New York law firm.

I said, “Dad, I want to go home. I want to run for office. I want to be involved in politics.” He just shook his head.

He passed away before I ran. I think he would have been at once pleased and horrified, because he thought politics was dangerous, financially difficult, and hard on families. And he was right about all those things.

But in the end, both politics and the law are opportunities to pursue justice. That has been my great passion.

* As this article went to press, it was reported that the first of four scheduled federal executions, cleared by a 2:00 AM order from the US Supreme Court, had been carried out, shortly after 8:00 AM on July 14; this note has been added in order to update the interview.