In response to:

“The Demolition of LACMA: Art Sacrificed to Architecture,” October 2, 2020

To the Editor:

Review readers should know that Joseph Giovannini’s article is as inaccurate as his many others on the same topic.

Far from representing a reduction in exhibition space, LACMA’s new building designed by Peter Zumthor, the David Geffen Galleries, is the final piece of a two decades-long expansion plan that effectively doubles the museum’s gallery space and replaces its ailing, nonfunctional facilities. The campus project as a whole, including three new buildings built between 2008 and 2023, comprises 220,000 square feet of galleries, making LACMA by far the largest art museum in the western United States. This huge achievement for Los Angeles is being made possible by hundreds of millions of dollars in private contributions from local sources.

Most important, Peter Zumthor and hundreds of museum design experts have shaped this new building to represent a forward leap in making art museums more accessible, and more responsive to our visitors, who want a more inclusive, non-hierarchical art history.

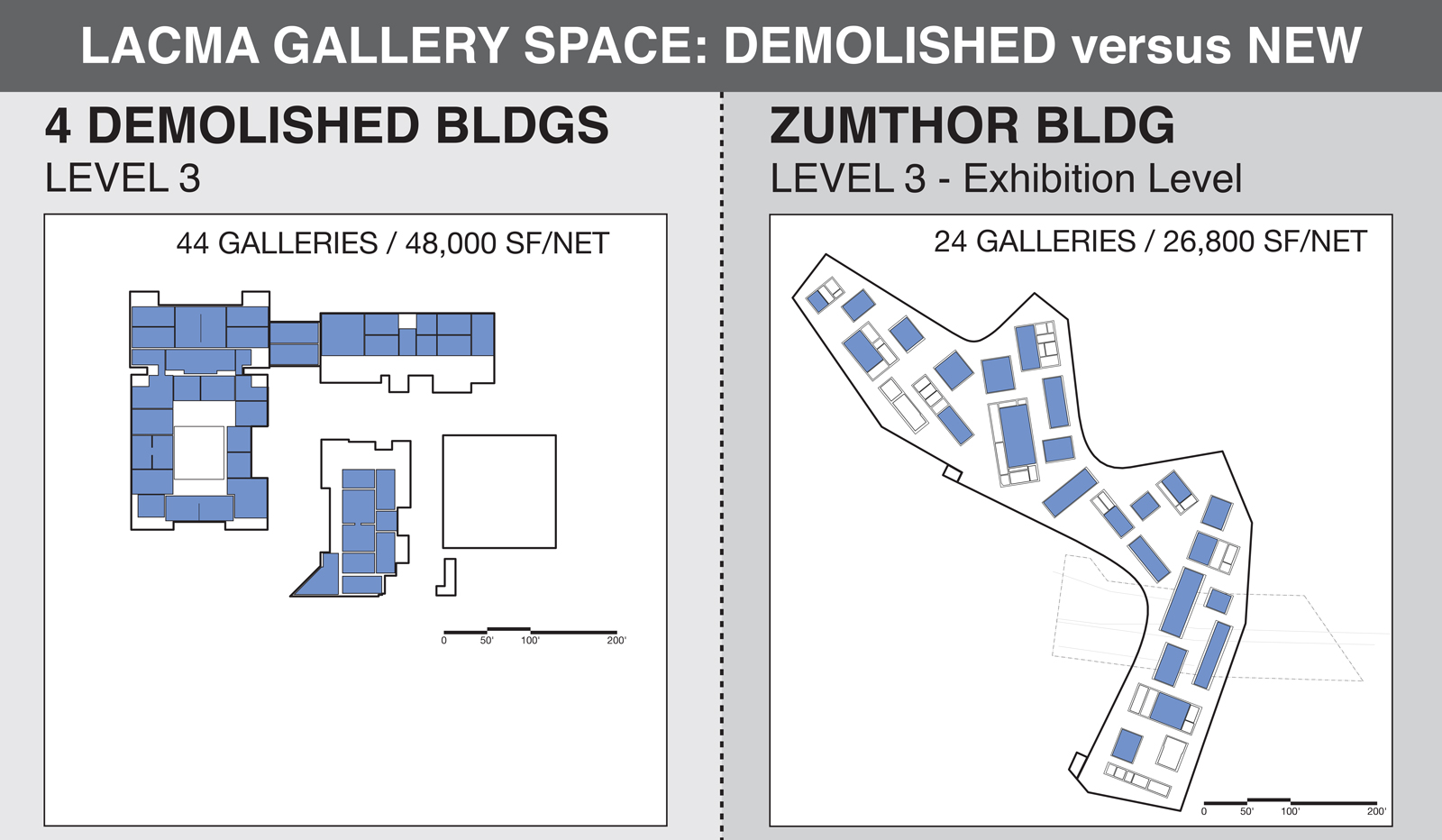

Sadly, Giovannini refuses to acknowledge the essence of Zumthor’s scheme for the exhibition floor, in which none of the space is wasted in circulation. More than fifty galleries will serve our collection not according to the categories of nineteenth-century art history but in keeping with the character of light the artworks require. Pointing to twenty-six “core” galleries that will provide complete light control for works of art that are especially fragile, Giovannini pretends that these are the only exhibition spaces in the building. He ignores the other types of galleries that offer the different light conditions required for different artworks and that were specifically requested by the museum. But much more of the space is devoted to the larger number of artworks that will thrive in the natural light and shadow provided by interior “courtyard” galleries and perimeter “terrace” galleries. It will be refreshing to experience art in its best light and not be lost in what previously was a rabbit warren of smaller, dark spaces that leaked when it rained.

Our curators are already hard at work crafting hundreds of proposals that will use these new spaces to present diverse aspects of our vast art collections. It’s true, we’re going to shake up art history a little, for the better: to be more inclusive, more egalitarian, and to allow more of our artworks to be seen over time in slowly changing installations. We’ll organize our collections in ways that reflect the best scholarship of the present. Our beautiful artworks can tell many stories, not just one that represents the limitations of colonial thinking.

Los Angeles has always been willing to lead art and architecture into the future. We’re doing that now. It’s exciting, and it’s meaningful, given the support of our county and city leaders, who reviewed the project thoroughly over a four-year, extensive public review period, and the enthusiasm of the many people who are asking museums to think differently. (It should be noted that in citing the petition drive against our new building, Giovannini is reporting on a project that was, in fact, his own initiative.) Fortunately, LACMA’s new building is now under construction, and in four years the proof of what we’re doing will be there for all to see.

Michael Govan

Chief Executive Officer and Wallis Annenberg Director, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Joseph Giovannini replies:

Michael Govan, director of one of the most comprehensive museums in America, is presiding over an unprecedented destruction of knowledge—a wholesale dump—while erasing the cultural identity of the very constituencies represented in the collections he purports to support. His too-small replacement building is forcing the collections into storage, never again to be seen as collections but as bits and pieces in theme shows, banishing bodies of knowledge that generations of curators have constructed. These are not “colonial” collections, as he dismissively claims. They are scholarly. They are works of art shaped by experts over time into cohesive, organic wholes. And as individual collections representing over a dozen cultures, they portray centuries of cultural accomplishment that come to life and into meaning when seen together, artworks commenting on one another.

The Zumthor plan is undoing the collections under cover of a poorly digested, piously presented poststructuralist argument about the value of cultural equity in a museum. A more inclusive, non-hierarchical art history is certainly a worthy goal that can be applied to any museum. But Govan’s critique of LACMA’s collections as expressions of a retardataire, culturally prejudiced, hopelessly Eurocentric institution are unsubstantiated by the collections themselves, which are in fact culturally diverse and correspond to segments of LA’s many cultures. Sending them into the anonymity of storage strips them of their diversity as cultural artifacts. They lose content and context.

Advertisement

The solution at LACMA could have been a course correction, not demolition—sensible, creative, even daring adjustments to the collections by addition, all within an expanded building whose adaptive re-use would have proved sustainably smart instead of profligate. Don’t blame the old buildings. According to my sources, the leaks and buckets that Govan cites as justification for the demolition of buildings “beyond repair” were caused by deliberately suspended maintenance. He caused the problem he claimed to be solving.

But even if a new museum were necessary, or just desired as a renewal expanding into the future, a new design that worked with, rather than against, the collections themselves should have been the goal. Frank Gehry started the design of Disney Hall from the travel of sound from the orchestra. At LACMA, the collections should have been the starting point for the design, not an afterthought that doesn’t fit. The architectural solution was either to reconfigure the existing buildings or to design a new building while keeping expanded, refreshed collections intact in a larger new building.

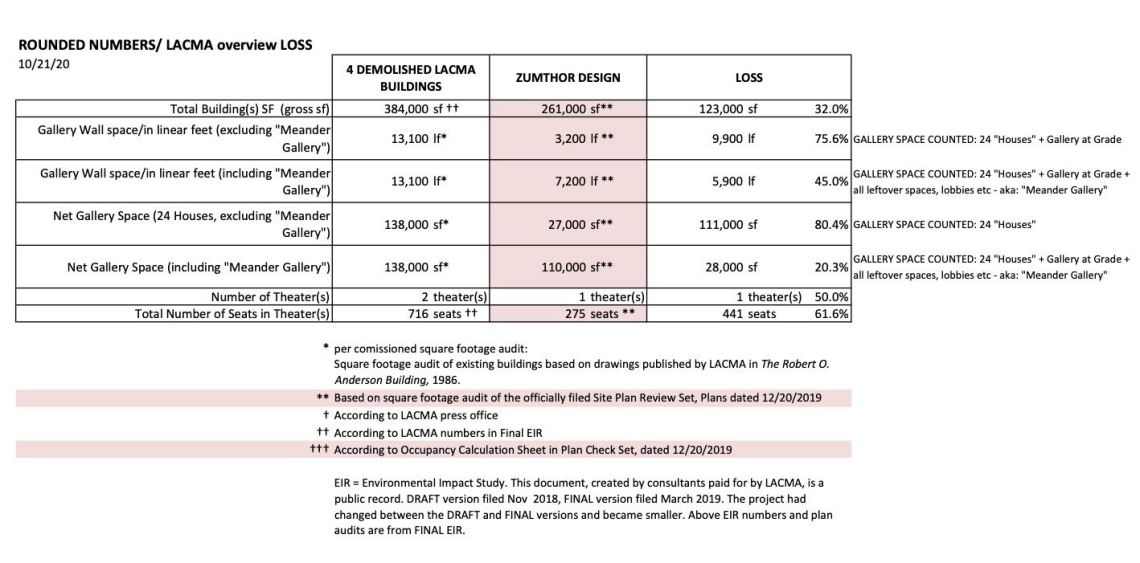

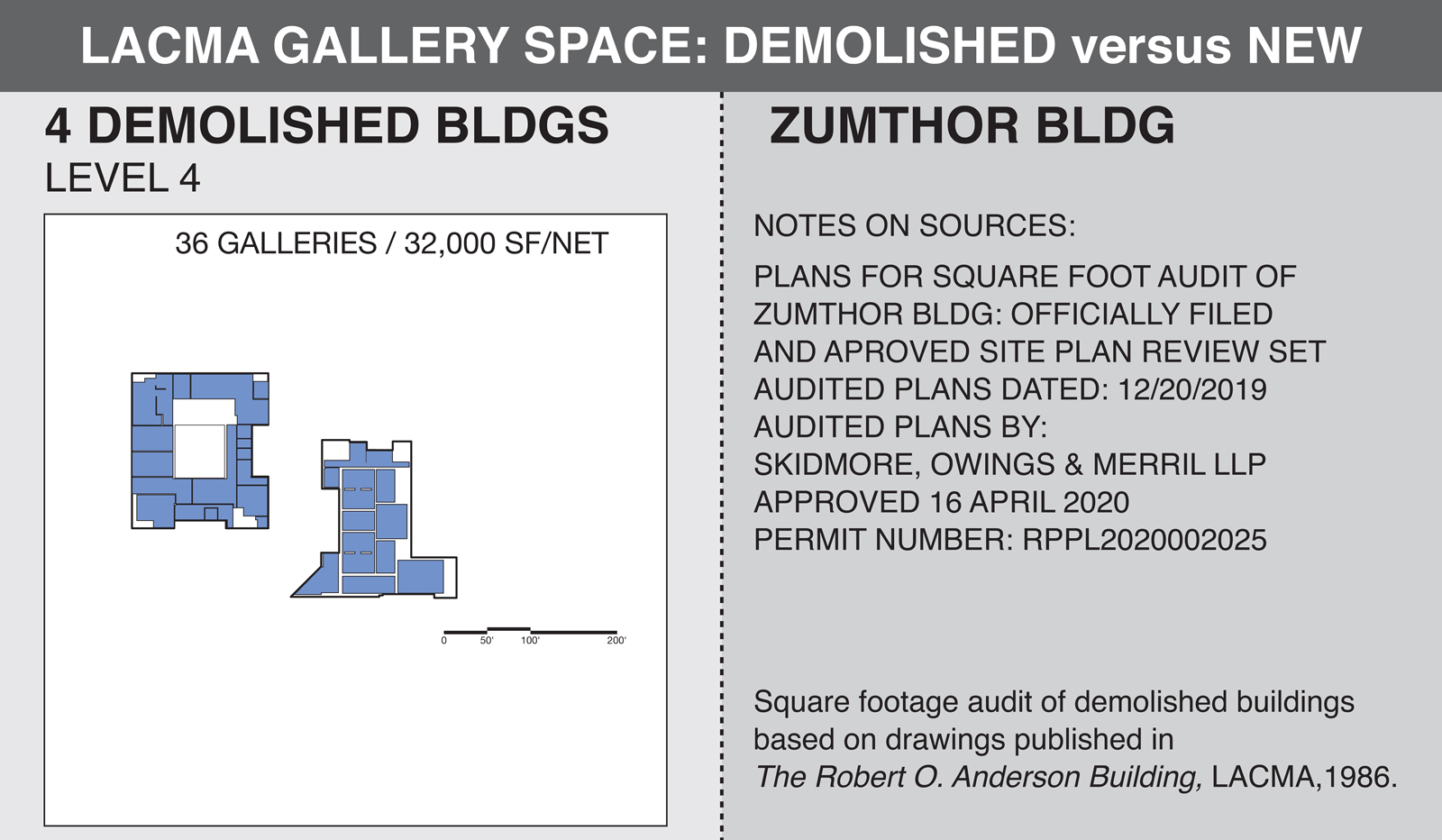

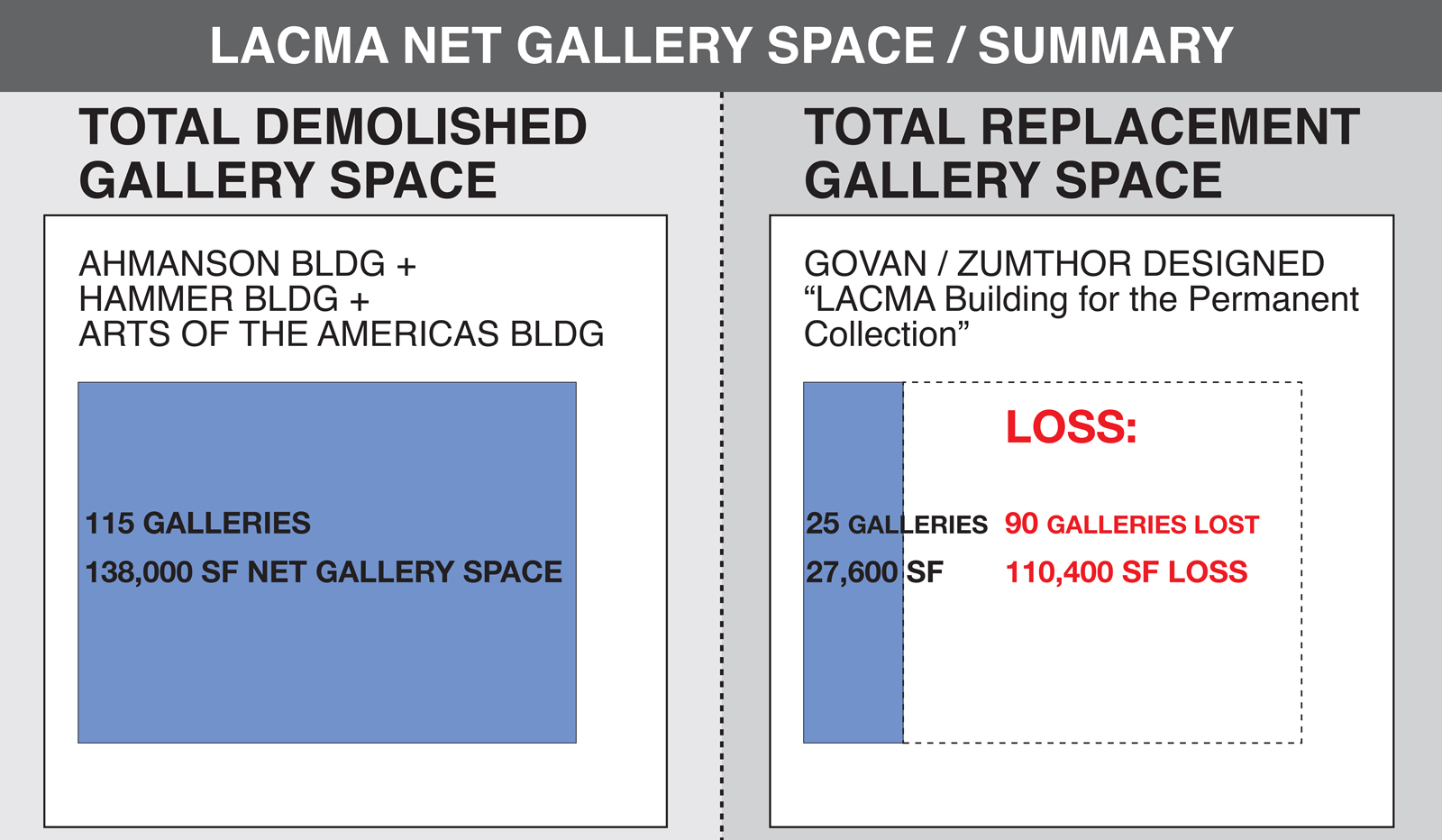

Govan essentially calls the facts in my articles “fake news.” The audited results of forensic studies done by two independent architectural groups prove that the whole building is 123,500 square feet smaller than those demolished. The figures below, some of which appeared in my original article, are now supported here with relevant documents. These are facts based on LACMA’s own original and recently filed drawings.

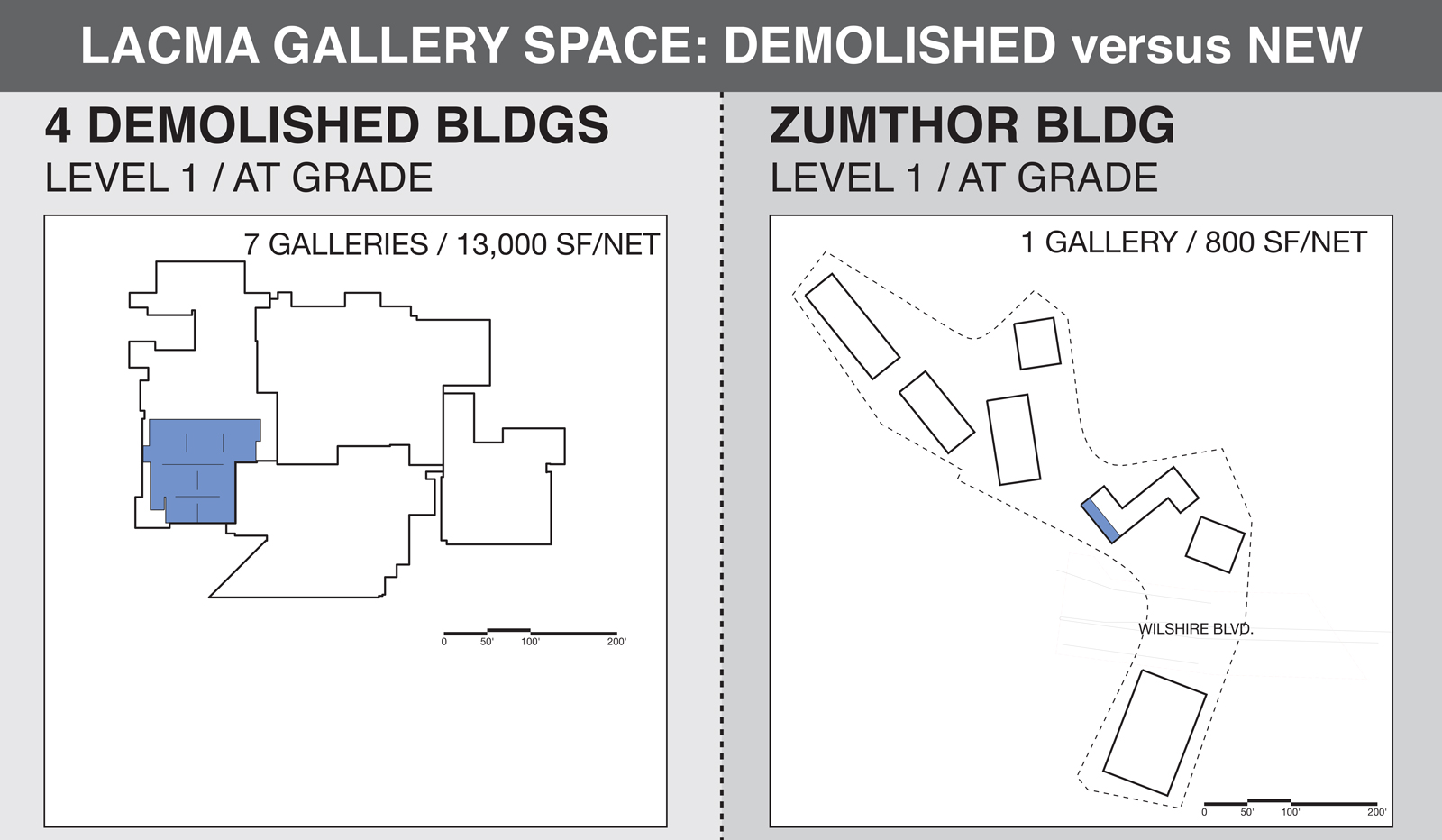

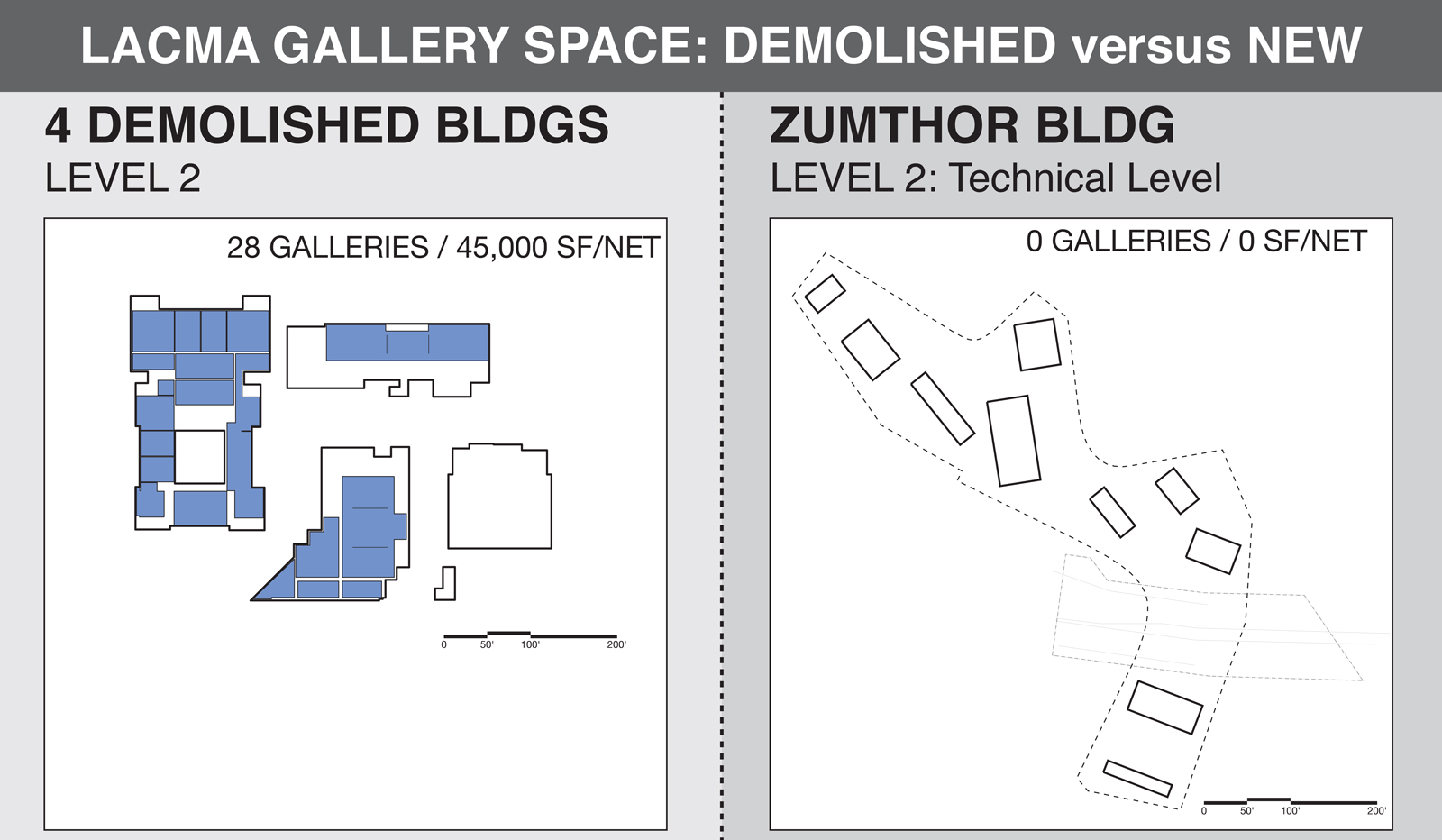

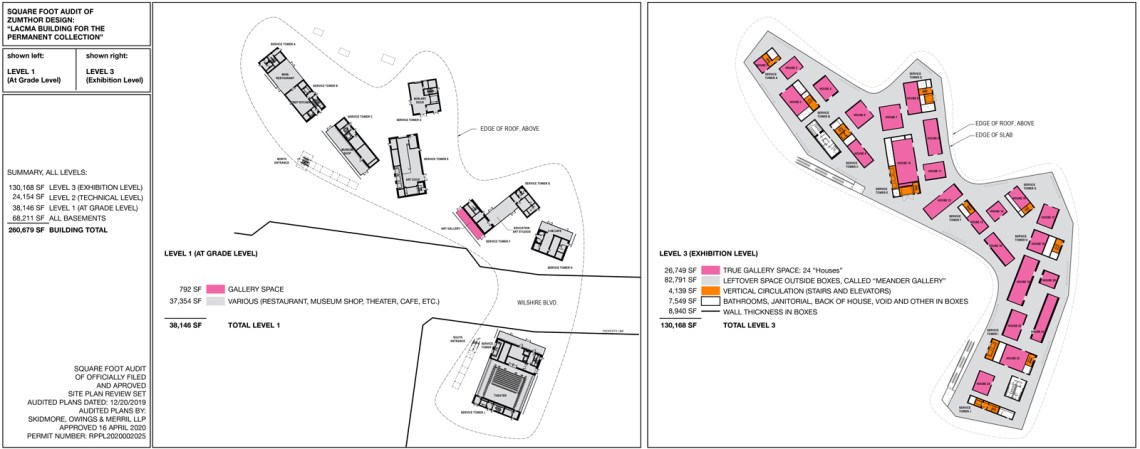

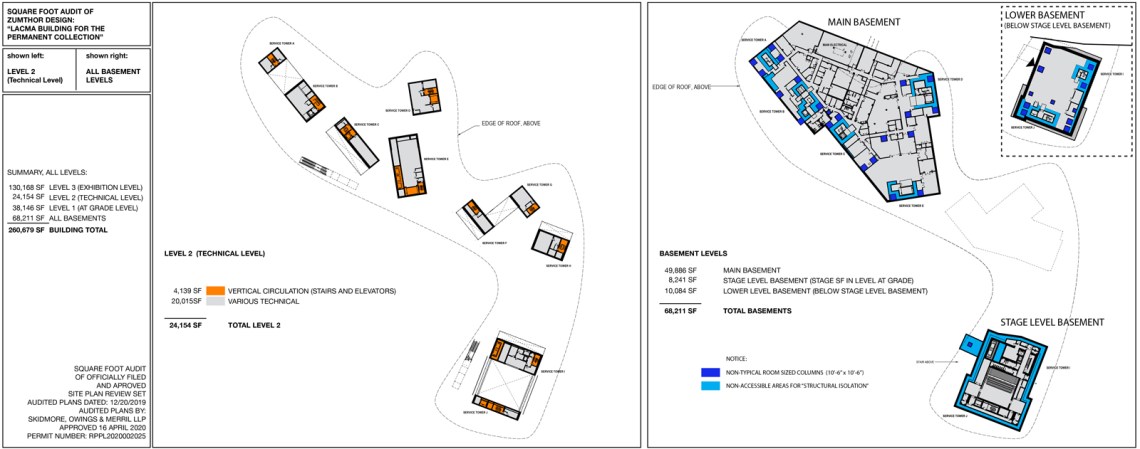

The plans below show that the Zumthor plan replaces 384,000 square feet of original buildings with a building with 261,000 square feet. Unbelievably, he is replacing 115 galleries in the old buildings with 25 boxes in the new (that is, 27,000 square feet of gallery space, instead of 138,000 square feet, or 80 percent less). He calls them “houses,” bizarrely advocating the museum as some sort of suburb of detached homes. He has invented an inflationary PR term, “meander gallery,” to apply to the 83,000 square feet of leftover corridors, or side yards, that would more honestly be called junk space. These are narrow corridors like hallways in a house leading back to the bedrooms—entrance lobbies, elevator lobbies, bathroom lobbies, and other accidental spaces. Like someone quoting the Bible for his purposes, Govan cites “natural light” as justification for leftover corridors he calls, in another inflationary term, “courtyard galleries” and “terrace galleries.”

Almost all of these spaces, especially the perimeter corridor glassed on one side, are subject to elevated levels of natural light severely restricting what can be shown, and therefore limiting what can be exhibited to a vastly reduced selection of objects, mostly sculpture. He has already dumped the collections, and now cuts by half what can be safely shown from the retired collections. According to one curator, the museum doesn’t even have that much sculpture.

Nor can Govan seriously count as interior museum space—as he tries to—some 65,000 square feet of outdoor space under the elevated belly and cantilevered roof of the building just because it’s covered. This is how landlords count space. The complete plans and square footages are displayed below:

Govan avoids a direct comparison between the size of the buildings demolished and their replacement because his numbers are indefensible, and so he asks us instead to look at what happened on the campus at large over a longer timeframe. But even under this premise, we are looking at a dramatic loss of space on his watch. Govan knows perfectly well but fails to mention—in a convenient bout of amnesia—that he lost 266,000 square feet of viable museum space when he forfeited the former May Company building to a hundred-year lease at 10 cents a square foot (rents on Wilshire are about $4.50 a square foot). He had over-extended his budget by building the Resnick Pavilion going into the 2009 crisis, and risked a credit-rating downgrade. A previous building that he counts in his numbers, the Broad Contemporary Art Museum, was initiated and funded by Andrea Rich, the previous director, so he can’t claim that as his achievement.

So, instead of a total gain of square footage on his watch, the total museum square footage actually lost is 344,000 square feet. This graph below shows a reduction of space on an epic scale unrivaled in American museum history: Govan turned black into red, gain into loss. Sadly, the chart of losses resembles Donald Trump’s income history during his casino period.

Govan knows, from his experience as deputy director working on the Bilbao Guggenheim as it was built, that architecture can define the image of an institution and shape it. At LACMA, however, in a perversion of architecture’s usual role as a constructive agent, he is using architecture to dismantle the very assets that established the museum’s stature. He degrades a ranking museum that before his arrival was on the verge of greatness, offering only a straw-man argument about “colonialism” to justify the building of an inefficient, land-guzzling, inappropriate, wildly expensive structure that, despite the PR hype, is, in the final analysis, only mediocre as design and highly dysfunctional as a building. He made the mistake of hiring an architect inexperienced at this scale, who was clearly operating out of his depth.

Advertisement

I’m glad that Govan mentions the petition, signed by 12,000 citizens, that I helped organize as a matter of civic duty. This was one of two independent petitions whose combined lists total 16,000 citizens, as I mentioned in my article, who are opposed to the building. The numbers tell the tale that matters: this is one of the most unpopular civic buildings ever proposed for the city of Los Angeles. Neither do the collections need it, nor do Angelenos want it. This building is an imposition of directorial will and ego, a raw example of building “architecture” for the sake of spectacle. Govan wanted to commission the equivalent of a Bilbao Guggenheim, and Los Angeles is paying for a spectacular failure with its collections.

This is also America’s loss. A museum of cultural scope that embraced the world now promises to become a provincial suburb.

The solution for Govan and his too-compliant board is to correct a problem of their own creation by shelving the Zumthor design and holding a competition for another plan.