Through a series of black-and-white photographs, printed the size of large landscape paintings, visitors to Josef Koudelka’s exhibition at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s François Mitterrand site encountered a world emptied of its inhabitants. The images in “Ruins,” from Tunisia, Libya, Spain, Greece, Italy, Turkey, and Syria, show ceremonial avenues trailing off into the distance and ancient city squares standing empty. Temple precincts are reduced to forests of truncated columns; the rows of empty stadium seats pile up like geological strata. At one time communal and ritual focal points, these ruins now seem haunted by the ghosts of those who once moved through them. These would be striking images regardless, but in a city, and wider world, that has been in on-and-off indoor isolation since last March, this was an exhibition of the ancient world with much to say about the current one.

Koudelka’s photographs explore the relationship between people and place. His images of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia necessitated his departure from his homeland, and the theme of exile recurs in much of his work. In 1970, having become a member of the international cooperative Magnum Photos, he received political asylum in the United Kingdom, later choosing to settle in France. In the images that comprise “Ruins,” the result of his travels around the Mediterranean between 1991 and 2015, Koudelka draws the viewer into the ancient sites through the interplay of light and shadow, with each image capturing a particular point in the day when the architectural elements and the passing of the sun come together, framed by the camera. Columns that have remained erect, or that have been reconstructed to stand again, are in perpendicular counterpoint to others now stretched out on the ground, their individual segments like a rack of car tires or a tube of peppermints. Flights of steps lead nowhere, their intended destinations no longer standing. In some images, a human presence is suggested by a maimed or crumbling statue—giant heads and hands, detached from their original locations, litter the ground.

The vast space of the BnF’s Mitterrand site, whose four book-shaped towers frame a largely subterranean complex, provided a suitably monumental location for the display. Now twenty-five years old, some of the trees planted in the site’s central garden, some thirty meters below street level, have reached a height where their top branches are visible from the surrounding sidewalks. Like the pines and cypresses that feature in many of Koudelka’s photographs, they seem to be sprouting amid the building’s shell.

If ever there was a time to meditate on the fragility of what may have seemed immutable, the ongoing global pandemic surely offers a harsh and poignant opportunity. The classical world knew well enough that plague, like its often-associated trials of famine and warfare, was frequently a check to the advance of civilization, if not an outright cause of its downfall. Photographs of Palmyra, Syria, by Kevin Bubriski and Don McCullin, as well as Koudelka, both before and after its violation by the forces of the so-called Islamic State, also remind us particularly that the transition from structure to ruin, from living culture to empty shell, is always, somewhere, a contemporary process. From the “traveller from an antique land” who narrates Percy Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias” to Charlton Heston’s agonized sighting of what’s left of the Statue of Liberty at the close of Planet of the Apes, the cultural idea that ruin also reveals some truth about the viewer and their time continues to resonate.

While Koudelka’s images attest to the passage of time, they also remind us of what endures. They continue to fascinate because they suggest that the achievements of the present world are relative—that our time is by no means the first, and won’t be the last, to use architecture to frame the communal, political, spiritual, and social lives of its inhabitants. Democracy, the system so recently stress-tested in the United States, is an ideal built upon the architecture of Athens. It is this aesthetic legacy of the classical world that successive ages have tried to harness, as if the fluted columns and pediments contained some essential order, gravitas, or dignity that could be passed on by replication.

But this legacy has a darker side. Classicism has often been the preferred aesthetic of authoritarianism, its motifs expressing conformity and discipline. The tightly bound rods of the fasces carried before the lictors in ancient Rome denoted the collective strength of the body politic, which is why they adorn the chair in which the statue of Abraham Lincoln sits inside his memorial in Washington, D.C. By the time that memorial was complete, though, they had also provided Benito Mussolini’s Italian regime with its name and defining symbol. The unity of the masses was publicly celebrated as the nation’s strength, while observers’ attention was diverted away from the physical beatings that the fascist squadristi inflicted on their political enemies.

Advertisement

The world of ancient Greece and Rome would also provide the defining aesthetic for the architecture of the Third Reich, framed in the theory of “ruin value” promoted by Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer, such that even the remnants of the country’s monuments would astonish future ages with their scale and grandeur. By 1945, Germany was indeed a land of ruins, but in a different sense. Those structures that had been built were blown up or torn down, while the scale model of “Germania,” the monumental redesign of Berlin as the “world capital” that Hitler so admired when he visited Speer’s studio, was itself destroyed when the real city was reduced to rubble.

Today, in the United States, classicism remains problematic. It is the defining style of federal buildings like the Supreme Court but also the architecture of the Confederate South. As Martin Filler pointed out in these pages, Trump’s championing of classicism as the default aesthetic for new civic structures, while simultaneously discrediting modern architecture as representative of values and ideology rejected by his administration, creates a worrying equivalence between classicism and authoritarian rule. On January 6, having heard him declare that the institutions of Congress had failed him, Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol, a purported display of “revolutionary” action that was in reality merely violence, looting, and symbolic desecration. Images from that day evoke not authoritarian order and discipline but chaos to the tune of the sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 CE.

As Koudelka’s images remind us, though, power, like glory, is transitory. Neglected, roofs fall in and columns topple. Stone is weathered by wind and rain. Statues lose their features, then their limbs. Materials are plundered for reuse on other projects. The city can be systematically destroyed as part of the vengeance of a conquering army, with its ruins left as a warning to others. Or its population may simply abandon it, drifting away in the wake of failed harvests or plagues to settle somewhere else, leaving behind only the physical remnants of a way of life that circumstances have rendered unsustainable.

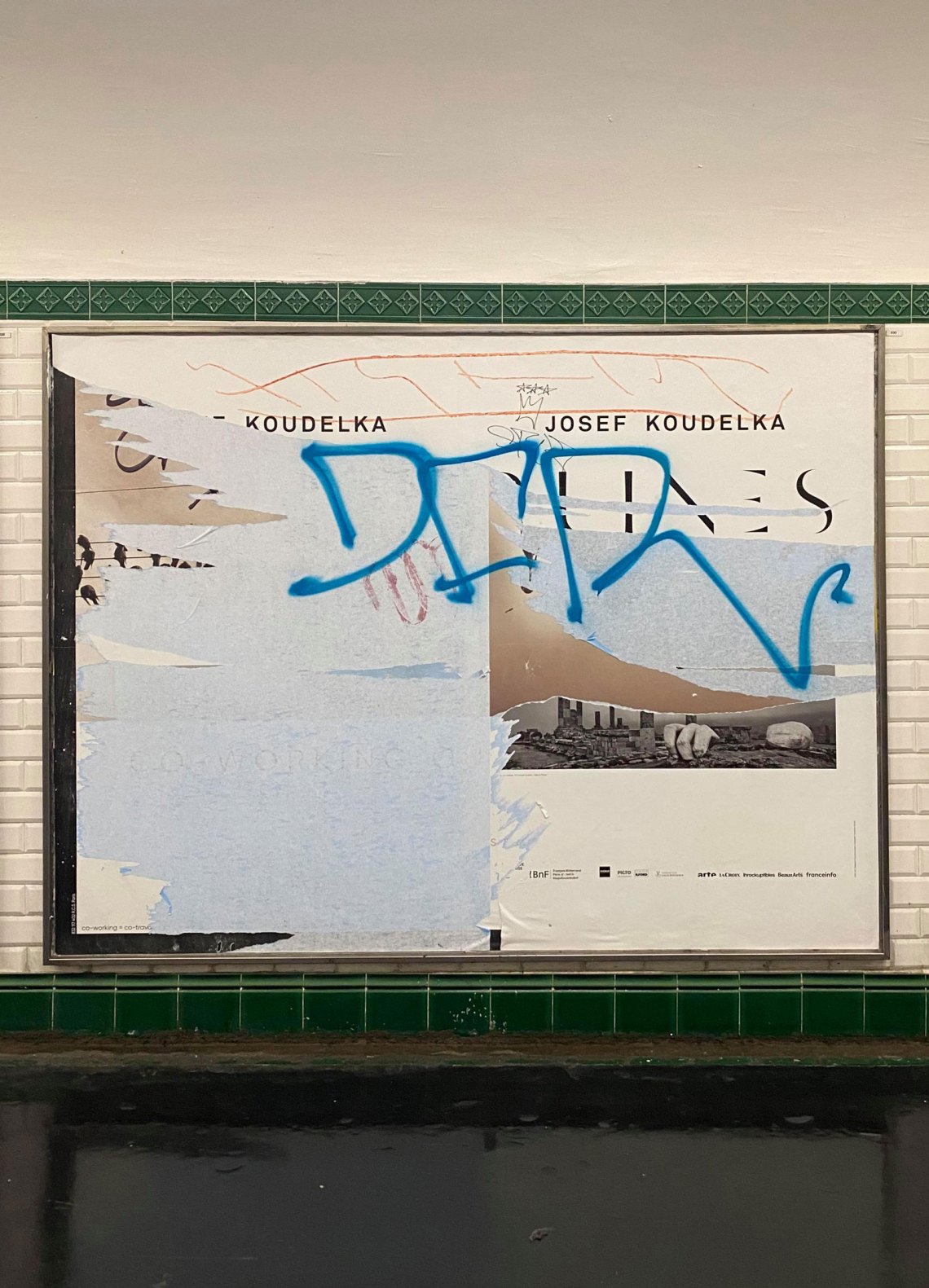

In the image selected for the exhibition’s poster, showing the Temple of Hercules in Amman, Jordan, three fingers from a giant disembodied hand rest on the ground in front of the few remaining columns of the structure. Only these fragments indicate what was once so prominently visible. As Paris emerged cautiously in mid-December from another six-week lockdown, a few of these posters were still visible in the tunnels of the city’s Metro stations, partially torn or defaced, themselves evocative of the ways in which this past year has given us all a keener understanding of how fragile our own civilization might be.