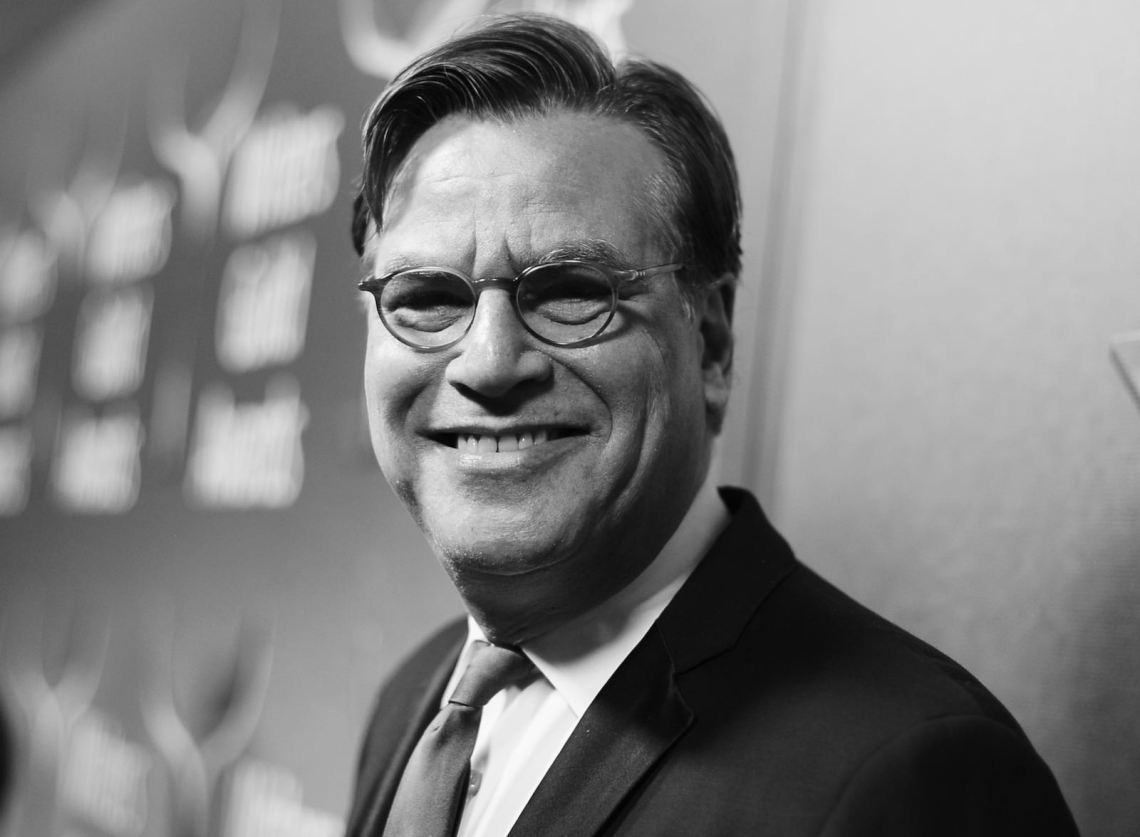

On the day after Joe Biden was finally sworn in as president, Aaron Sorkin, the United States’ preeminent political dramatist, seemed as relieved and happy as anyone. But for the writer, now nearing sixty years of age, of a dozen movies, four television series, and six stage plays, the moment has a special significance: best-known for his four seasons of NBC’s Emmy-winning The West Wing, he has built an entire career on the political drama of American democracy.

Sorkin’s screenplays—among them, The American President, Bulworth, The Social Network, and Charlie Wilson’s War—examine different aspects of American life. His most recent, The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020), is built around a courtroom drama at the height of the tumult, strife, and division of the late Sixties. And in 2018, Sorkin boldly adapted Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, updating its story of racial injustice and individual conscience from the pre-Civil Rights South for Broadway audiences in the era of Black Lives Matter.

There have been plenty of writers in the past who made theatre out of political themes—Gore Vidal, Dory Schary, and Robert Sherwood, to name but three. Many filmmakers, too, have asked hard questions of American democracy in movies such as All the King’s Men, A Face in the Crowd, The Last Hurrah, and The Candidate. But it is hard to think of another writer who has made the “American experiment” of self-government their singular subject with anything approaching Sorkin’s single-minded devotion.

After a period of political histrionics in Washington, D.C., like no other in modern American history, it seemed a propitious moment to ask Sorkin what he made of it all. What follows in an edited and condensed version of our recent conversation conducted via Zoom.

Claudia Dreifus: How would you rate the theatre of the Biden-Harris inauguration?

Aaron Sorkin: It struck just the right note. Biden’s speech was the sight and sound of normalcy. Add to that Kamala Harris’s being inaugurated. And Amanda Gorman and her recitation—as a writer, I can’t get over how much game this young woman has.

To me, it all felt like a cool breeze. It still feels that way. I know things will happen—the honeymoon doesn’t last—but I am enjoying it while we’re on it.

I am well aware that a big problem still remains. Seventy-four million people looked at Trump and said, “I buy that.” For some reason, tens of millions of people think that the election was stolen. That’s a big problem. We have to figure it out.

The Greeks taught us that great theatre allows catharsis. Did the inauguration do that for you?

Cynically, you could say that, rather than a catharsis, it was like the world’s worst and longest play had just ended. The curtain came down and it was over—and we’re just so happy that we can get out of our seats and end at a much better place.

Now, here is where the catharsis comes: Amanda Gorman’s line that went, “Somehow, we’ve weathered and witnessed/A nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.” The catharsis is that we know that democracy did survive. That was a close one; we never want to come that close again.

We saw Americans not protest, but attack the Capitol. And they did it because they have been pumped full of bad information. It seems to me the crux of our problem is how do we make the First Amendment and the necessity for us all to agree upon facts live together?

We also witnessed a second drama on Inauguration. The nation’s first female vice president—the daughter of immigrants from India and Jamaica—swore two senators into office from the State of Georgia: one was a black minister and the other a Jew. Georgia was the scene of countless lynchings of African Americans, and it was where Leo Frank, who was Jewish, was lynched in 1915. Did the symmetry of that strike you?

Sure. I actually got emotional a few days earlier when I saw they were going to win the runoff elections. The gospel songs are right, I thought: change comes fast and change comes slow, but change comes.

You had a character on The West Wing who was identifiably Jewish. How would he have viewed the Georgia moment?

Toby, Richard Schiff’s character, would’ve loved the Georgia moment. But I also think someone like Toby, who is just hardwired to step back while everybody else might have been high-fiving, would’ve been saying, “Be careful of what the backlash in Georgia is going to be. There are people who don’t like seeing Democrats, Black men, Jews, representing Georgia, and they’re not going to take this lying down.”

Advertisement

In The West Wing, your fictional president, Josiah Bartlet, was a principled liberal who sought to move the country forward. The drama often came in the compromises he made—or didn’t. Did you write the series as a kind of alternative to the conservative politics that we were living though during the years the show aired, which was 1999 to 2007?

No, the engine underneath The West Wing wasn’t a reaction to our actual politics. Our first season was Bill Clinton’s last year in office. It ran through George W. Bush’s first term and half of a second term. And it had nothing to do with any of that.

I am in no way an expert on politics, and I am very conscious of that. I just find politics a great story-telling arena. If you like writing idealistically and romantically the way I do, it’s a good pool to swim in.

By and large, in pop culture, our elected leaders have been represented either as Machiavellian or as dolts. I wanted to do a show—a workplace drama set at a very interesting workplace, the White House—where the people who work there were as competent and as dedicated as the nurses and doctors on a hospital show.

There is a tradition of movies about American politics, but why had there been nothing like The West Wing on television before?

Shows about politics had always failed on television—as everybody assumed The West Wing was going to. When I was writing the first episode, I didn’t think there’d be a second episode.

Not only was it about politics, but people were pretty overt about their politics. The characters had strong opinions. It turned out that viewers stuck around because they liked the characters—even people who disagreed with them.

In 2016, the morning after Donald Trump won the presidency, you sent your then thirteen-year-old daughter a letter that was later reprinted in Vanity Fair. In it, you called Trump an “incompetent pig with dangerous ideas, a serious psychiatric disorder, no knowledge of the world, and no curiosity to learn.” Did you foresee things unfold as they did?

I couldn’t have imagined it. I thought that what he was going to be was an embarrassment—a buffoon propped up by people who knew what they were doing. And I thought: Their politics don’t align with mine but at least they knew what they are doing. They’ll respect democracy, at the very least.

The thing I couldn’t imagine was somebody ordering that children be taken from their parents at the border; The single easiest thing in the world for one parent to do is to empathize with another parent. So, I couldn’t imagine that. The white supremacist stuff, I’m not surprised he went that way. But I was surprised that he kept saying the quiet part out loud. And I was surprised by how many of the people around him were just straight-up corrupt, dead-on criminals.

So yes, even with my very low expectations, I was shocked, almost daily.

And those expectations?

At first, I thought, the government would just keep on rolling along. He wouldn’t do anything about climate change and maybe we’d stumble into a dumb war. But I never imagined what actually happened because it wouldn’t have without the cooperation of the Lindsey Grahams, the Mitch McConnells. I was shocked by every Republican in the House and almost every Republican in the Senate who enabled him.

I never imagined grown men and women just lying to people the way they did. And I never imagined the tens of millions of Americans being as gullible as they are.

You know, the presidents we think about as bad, whether it’s Richard Nixon or Herbert Hoover, they still colored [the pad] inside the lines of an understanding of what it meant to be president. Neither of those two were as jaw-droppingly stupid as Donald Trump is.

Is there a novelist or playwright who could produce a believable work of art based on a Donald Trump character?

I hate speaking for other writers, especially other writers more talented than I am, but I don’t believe any writer could.

I believe that right now, America’s best living writers (I mean playwrights, screenwriters, not novelists)—Tony Kushner, David Mamet, and a few others—if you gave them all the time in the world, they could not write that character in a way that would make a play or a movie work.

Advertisement

You can only have him as an offscreen character that other people are talking about. Now those could be interesting and dramatic conversations: between people around him, most of whom know better, and who were being put through something. That’s drama. That’s interesting. He is not.

The other thing that disqualifies him is that there’s no such thing as an interesting hero, or even anti-hero, who doesn’t have a conscience. At least with Richard III, stuff does weigh on him. That’s what makes the play so gripping. Nothing weighs on Donald Trump except his various metrics of popularity. He’s a thug, a cartoon thug. He is a mobbed-up imbecile.

So how did he win the 2016 election?

I think that there’s more than one reason. One is that Trump was an excellent stick with which to poke liberals in the eye. This may sound masochistic but I make it a point to regularly check out Breitbart. The common theme for the last four years has been “I just love how mad he makes the liberals.”

There are people out there who feel that people like me and you think that we’re better than they are. I’m convinced that one of the reasons he got elected is because of a debilitating inferiority complex on the part of tens of millions of people.

You know, we all jumped up and down on Hillary Clinton when she said that half of all Trump supporters could fit into what she called “a basket of deplorables.” But there is no such thing as a Trump supporter who is not deplorable. By being a Trump supporter, you’re saying, “I’m not a racist, I’m just cool with racists. I wouldn’t separate families at the border, but I’m cool with it because it gets me other things I want.” That’s deplorable.

Do you see Trump as a classic sociopath? It’s what his niece, Mary Trump, suggested in her memoir Too Much and Never Enough. I think I hear you hoping that someone could come along and write him in a way that we can say, “Oh! I get it. There’s the humanity.”

I don’t believe it can happen if you are authentically writing Donald Trump. I’m not comfortable referencing myself, but let me give an example from A Few Good Men. The Jack Nicholson character has this speech on the witness stand where he says, “You can’t handle the truth.” He makes a defense of this Marine who got killed, why that was actually a good thing.

The power of that speech was that a bad guy was making a good point. He may have been deranged, but he was a very smart guy. Donald Trump is not.

The Capitol invasion on January 6. In all your dramas, could you have conjured a scene like it?

I could not.

While I was doing The West Wing, we did a documentary, which we aired one week instead of a rerun. We hired a terrific documentary filmmaker and we interviewed people who had worked in White Houses going back to Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. One of the people who was interviewed, Lanny Davis, who was Bill Clinton’s special counsel, told the story of putting his kids in the car when Richard Nixon resigned, in August 1974. They drove as close to the White House as they could, and he said, “Look, kids, the most powerful man in the world is going to hand over power to someone else at noon today, and you don’t see a tank in the street. That’s America.”

That we were not able to give our kids that same sort of lump-in-the-throat lesson is going stick with us.

When you wrote The Trial of the Chicago 7, did you plan it as a comment on the current moment?

God, no! First of all, I started writing the movie fifteen years ago. On a Saturday morning in 2006, I was asked to come over to Steven Spielberg’s house. That’s not common. I don’t hang out with Steven Spielberg. He said he wanted to make a movie about the Chicago Seven, and he wanted me to write it. I said, “That sounds great, count me in.”

As soon as I left his house, I had to call someone to ask them who the Chicago Seven were. I had no idea. I was just saying yes to doing a movie with Spielberg.

Then I began my research. There are more than a dozen good books written about the trial, some by the defendants. There’s a 21,000-page trial transcript. I talked with Tom Hayden, who was still alive when I began. But to answer your question: I always wanted the movie to be about today and not about 1968. In the last fifteen years, I’ve written twenty-five or thirty drafts, but only to make it better in the way a screenwriter would. I never made any changes to reflect events in the world. Events changed to reflect the script.

Ironically, on January 6, Donald Trump committed the exact crime that the Chicago Seven were charged with.

Do you think Trump could be charged?

Yes. And I assume that those people who crashed the Capitol and were not from Washington, D.C., crossed state lines to get there. So, for good measure, they could also be charged. It was the exact same crime.

If Trump isn’t prosecuted and if his second impeachment doesn’t result in a Senate conviction, might a kind of Truth and Reconciliation Commission—as existed in South Africa, Chile and Argentina—be an answer?

We need something. First of all, there needs to be a commission. We need to understand what happened on January 6. We need to understand what happened for the last four years.

This isn’t about chasing Trump to the ends of the earth, as though he’s Butch Cassidy and we’re the posse. This is about the rule of law. And this is about the future. I don’t think American can continue with tens of millions of its voting age citizens as certain in their misinformation as they are.

For more than four years, Trump and whatever he did were at the center of our lives. He inhabited the national consciousness in a way that no president before him had. Will we, despite ourselves, miss his reality show?

You’re right about Trump being in the air supply. Sometimes, I get in trouble for being publicly optimistic. Still, let’s take this moment to be optimistic…and stipulate that Trump will find a way to be heard, but it won’t matter because he’s just a guy in Florida, being cranky about Biden and Harris. Out of office, he’s not going to get nearly as much coverage as he did when he was in the White House.

I think it’ll happen roughly the same way we stopped talking about certain cultural moments—like the Balloon Boy hoax.