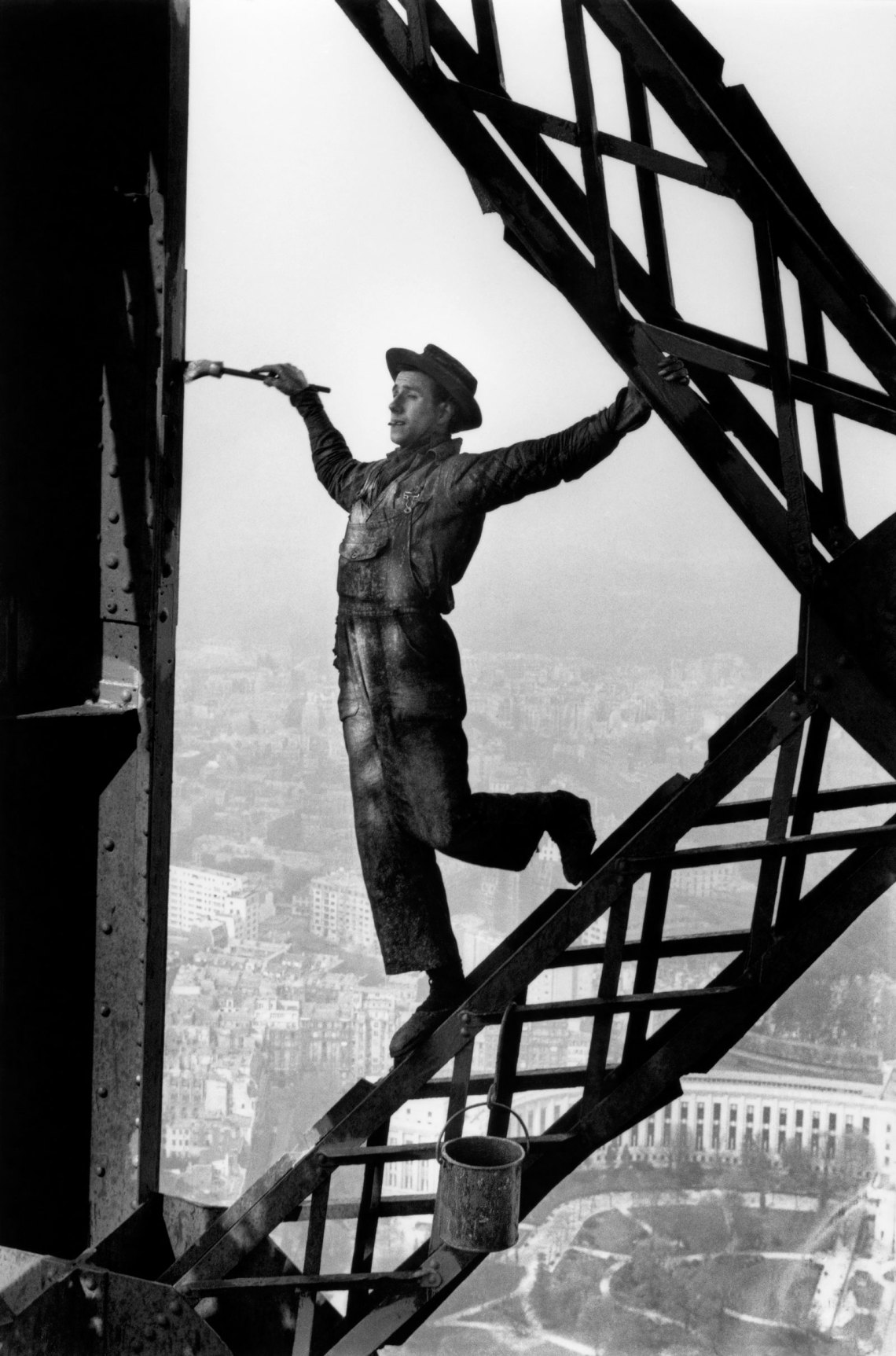

In the spring of 1953, Marc Riboud left Lyon, France, for Paris. He was thirty years old. The Eiffel Tower was being repainted. Equipped with just one roll of film, Riboud climbed up the perilous spiral metal staircase and caught sight of a solitary painter.

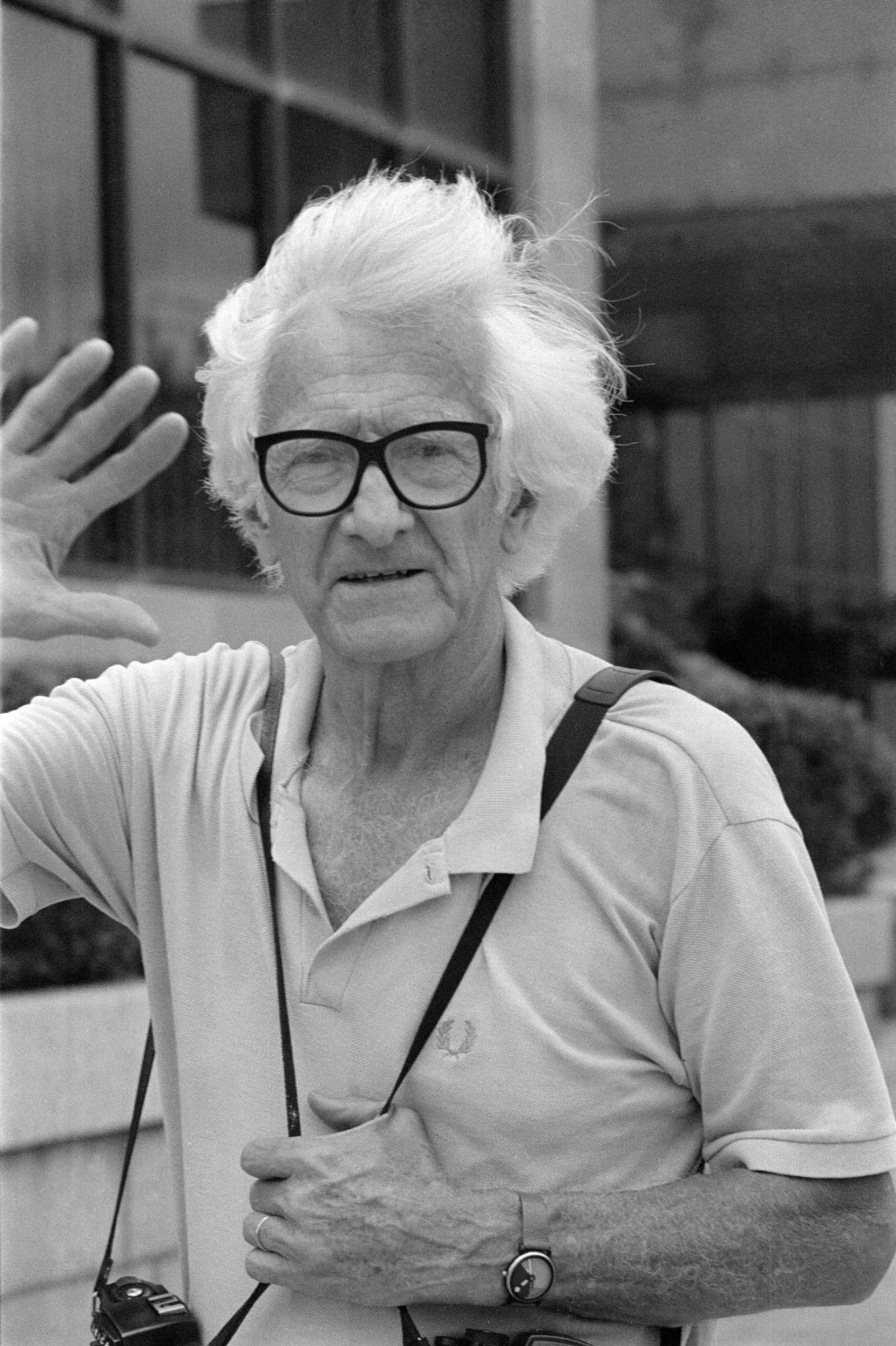

The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom Riboud had recently met, had persuaded him to screw onto his Leica camera an old viewfinder, which showed the image in reverse. Renaissance painters, the older photographer had explained, checked the composition of their painting by looking at its reflection.

When Riboud saw the painter upside down in the viewfinder, he lost his balance—a shot, he later remarked, that “almost made my very first photograph my very last.”

But luckily, he held on, and his first professional photograph brought him instant fame. The image, which captured the acrobatic grace of Zazou the painter, framed impeccably by the triangle of the Tower’s iron joists, his tilted hat, cigarette, and espadrilled feet evoking Buster Keaton, was published in Life magazine with the caption “Blissful on the Eiffel.” This early success helped the young Riboud join the Magnum Photos cooperative, with which he would remain for twenty-six years.

Born in 1923, the fifth of seven children in a Catholic French family, Riboud was so painfully shy as a child that his father gave him his old camera, a Kodak Vest Pocket, with the counsel: “You don’t know how to talk, but maybe you will know how to look.” Early on during World War II, just after his father’s death by suicide (he had fought and was decorated during World War I but could not stand the idea of yet another war), Riboud joined the Resistance. After the war, he studied engineering but, unhappily confined by the monotony of the work, he quit after one week into his first job.

As an adolescent, Riboud had pored over books by Cartier-Bresson, Brassaï, and Robert Doisneau, finding refuge and meaning in their images. Photography now seemed an escape from the constraints of his childhood city—a path toward discovery of the wide world and, perhaps, of himself.

A retrospective now at Paris’s Musée Guimet displays more than three hundred of Riboud’s photographs. Among a group of early images made in postwar Europe, a series taken in the former Yugoslavia includes a wonderful image from 1953 Dubrovnik: a young girl in a bikini runs ecstatically toward the photographer under her grandmother’s disapproving eye; extended like a wing, her right arm appears to brush against the old woman’s gray apron—a trick of perspective—as if bridging the mental and generational chasm between the two women.

In another image—a striking, cinematic shot from a slightly elevated point of view in London—Liverpool dockers protest compulsory overtime in 1954 Hyde Park; attentive and tense faces fill the frame, each expression individual, reminiscent of an image by David “Chim” Seymour, a cofounder of Magnum, of tenants and laborers at a meeting for land re-distribution in 1936 Spain. As Riboud’s colleague Gilles Peress explained, Magnum photographers who started their careers in the mid-1930s during the Popular Front were united in their left-wing politics and support for the working class.

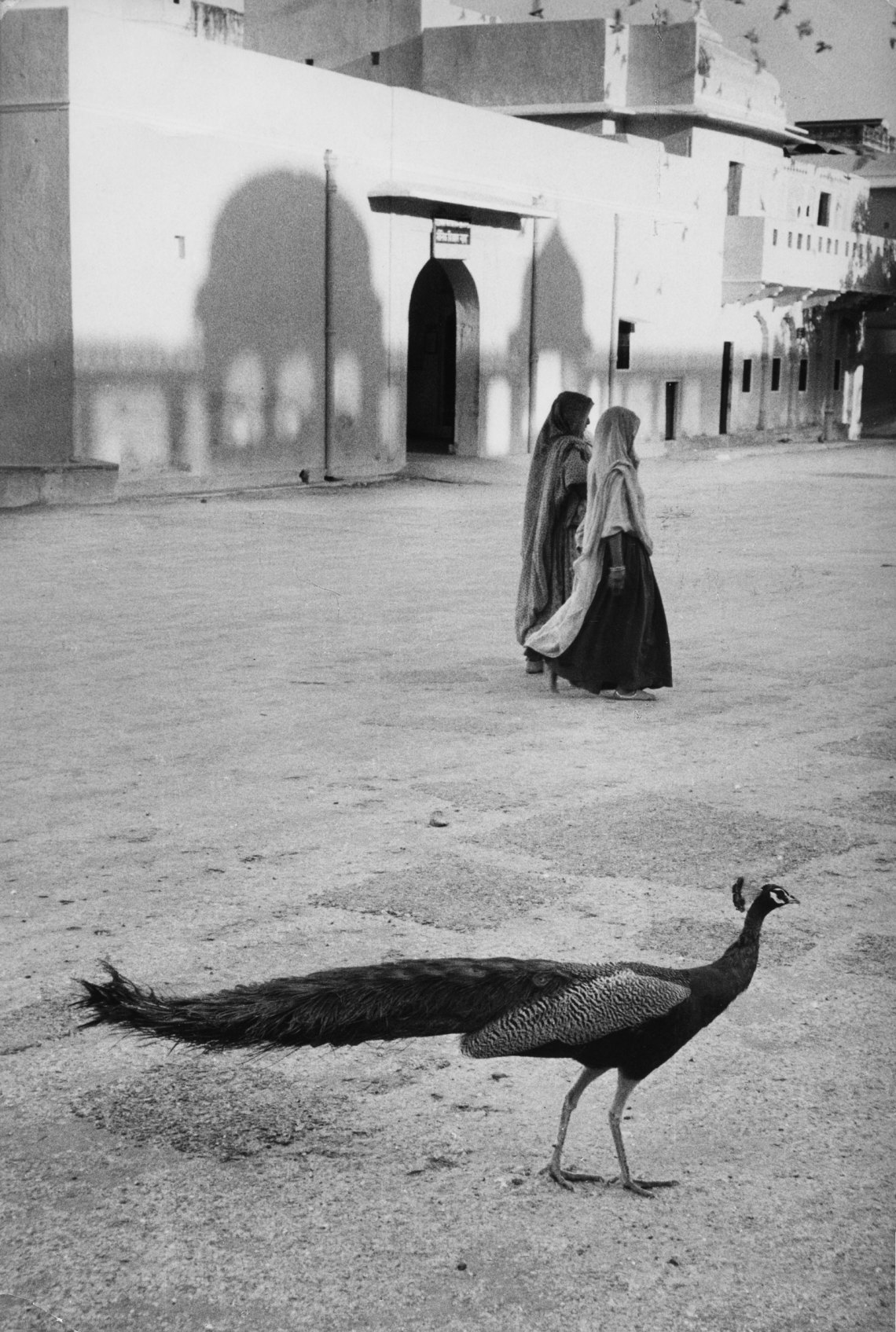

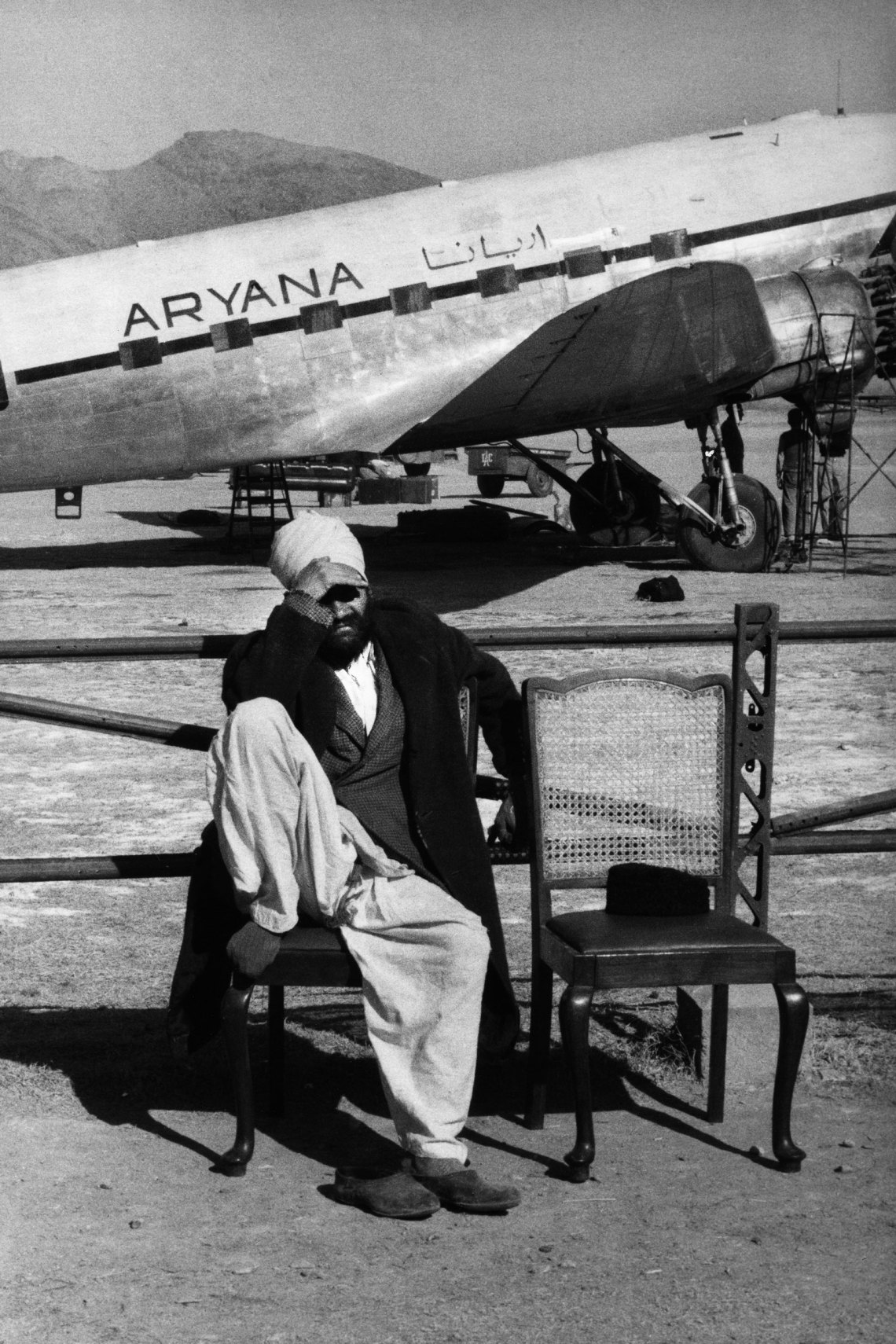

Riboud was guided by the four Magnum founders: Cartier-Bresson, Seymour, Robert Capa, and George Rodger. The latter became a kind of godfather to Riboud, generously offering him one of his own assignments in Lebanon. In 1955, Riboud took off in Rodger’s old Land Rover and started wandering with no plan across the Middle East and Asia, working his way through Turkey, Afghanistan, and Iran. He pushed on to India, where he stayed with an Indian family in Calcutta for a year, and there met and photographed the filmmaker Satyajit Ray and the musician Ravi Shankar. He continued on to China, Japan, and Indonesia—all the while sending images back to Magnum.

It was late 1957 by the time Riboud returned home. But his wanderlust was not satisfied: attracted by the idea of silence and the natural world, he soon left again, this time for North America. There, he followed the 1,600-mile road leading all the way from Dawson Creek in Canada’s British Columbia to Fairbanks, Alaska, and then flew to Kotzebue, an isolated village in the Western Arctic.

During these early trips, perhaps in part because of his shyness, Riboud was incredibly adept at recognizing and capturing expressions through body language: the resolute yet lonely and longing stance of the young Turkish boy in his tattered jacket photographed from behind, looking at the harbor from Istanbul’s Galata bridge; the distrustful, uncertain gaze of the Afghan boy contrasted with the open and curious eyes of the baby brother he carries on his back; the tired, still pugnacious expression of an aged Winston Churchill reading a leaflet in 1954 at the Conservative Party’s annual conference in Blackpool; the fixed, almost hallucinatory glare and tense hand of the Pakistani boy in an arms factory, the gun he clutches hiding half his face.

Advertisement

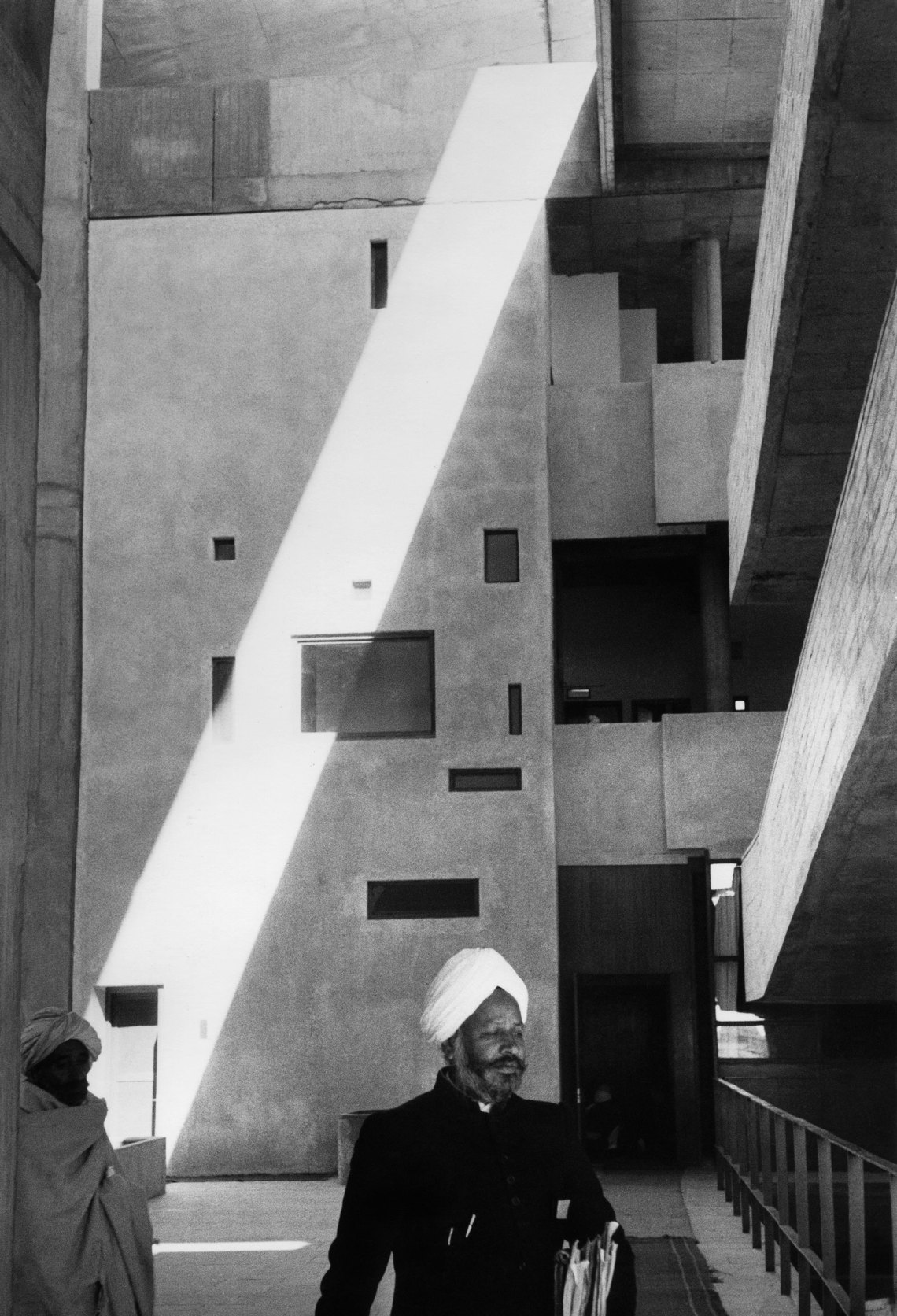

In one of the photographs Riboud took in Le Corbusier’s modernist, concrete city of Chandigarh, north of New Delhi, his gift for composition shines. A man in traditional kurta and white silk turban walks, his eyes lowered. Duplicating the line of the building’s balconies, a parallel slant of light slices the facade to illuminate a second, seated character who looks back at the photographer. With its carefully held tensions and tight geometries, the photograph seems to embody India itself in that moment, poised between past and future. Riboud once said: “Photography…cannot change the world, but it can look at the world as it changes.”

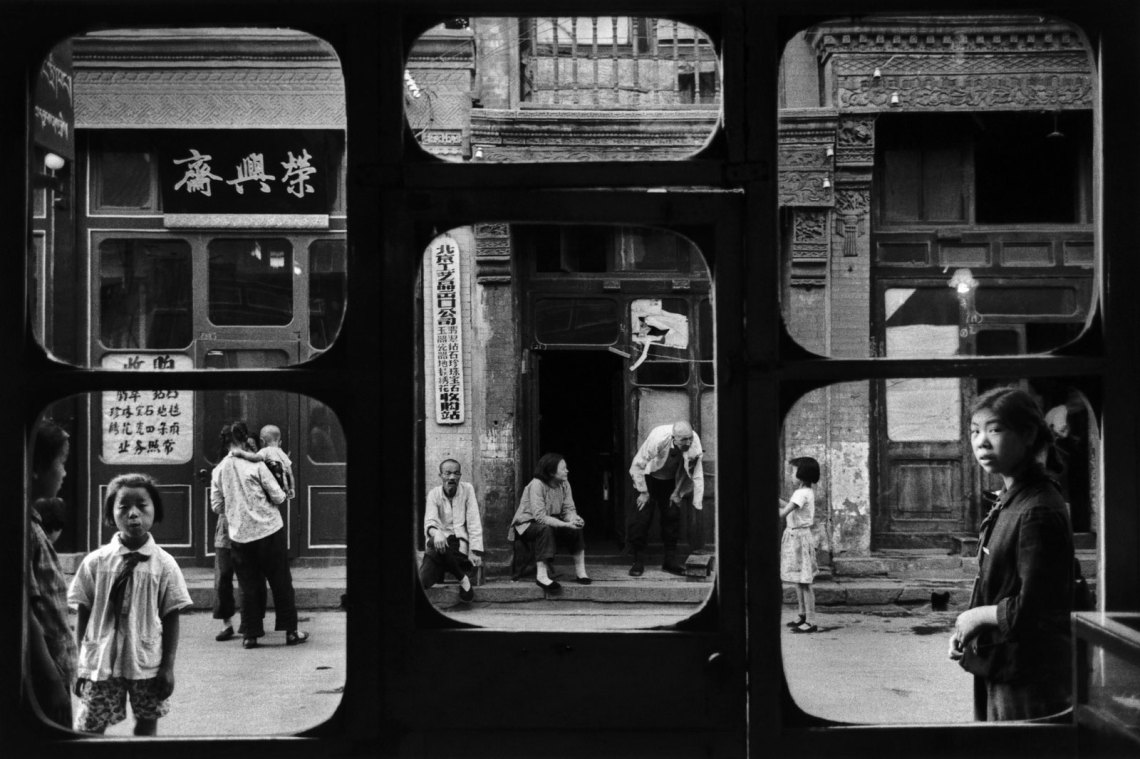

Riboud often used mirrors or windows as a device to frame or distance, as in a complex image made at Nigeria’s Independence Ball in 1960: a passing woman and her shadow, projected on glass, mark the border between the outside, where a woman in evening wear is seen exiting a car, and inside, where couples are dancing. In a 1965 image taken from within an antiques store in Beijing, each of the six panels of the shop window frame a different fragment of a street scene, evoking a nineteenth-century cutout photo album. In an earlier photograph from Iran, the subjects, seemingly reflected in a mirror, are unaware of the photographer; the athletes, rolling on their sides, are arranged in a circle practicing zurkhaneh, a traditional gymnastic warrior training ritual. The image’s blur emphasizes their movement. These particular photographs, more nostalgic than political, capture traditional customs and ways of life rendered ever less visible as modernization spread.

As with the shot from Nigeria’s independence celebrations, Riboud was drawn to photograph the period of decolonization in the 1960s. In the summer of 1962, on Independence Day in Algiers, two boys hoisted Riboud on a truck’s skip and from his perch he photographed the boisterous joy of the people in their first hours of freedom from French rule. From 1958 to 1963, intent on seizing the political moment, he documented the struggles for independence across Africa: from Guinea and Ghana to Nigeria, Kenya, and Niger.

In 1967, in the United States for the second time—he had attended his own retrospective at the Art Institute in Chicago three years prior—he witnessed the anti-Vietnam War march on the Pentagon. As dusk set in, most journalists left. Always tenacious, Riboud stayed on, spotting a seventeen-year-old Jan Rose Kasmir advancing toward a policeman’s bayonet holding a daisy like an offering or a prayer. The photograph was the last shot on his last roll of film. First published in Life, Riboud’s image, and the protest it documented, were credited with helping to turn public opinion against the war.

This success inspired Riboud to continue covering protests around the world: the following year, with his colleagues Bruno Barbey and Cartier-Bresson, he photographed the student demonstrations in Paris; in 1971, he shot the Indo-Pakistani conflict; and in 1979, the Islamic revolution in Iran. It was around then that I met Riboud, when I was reviewing his 1980 book on China. We discussed the situation in Poland, where we were both heading—separately—to cover the Solidarność (Solidarity) rising. We remained friends, and when I started writing about Magnum, he generously shared his memories with me.

As the publisher Robert Delpire wrote, Riboud “conveys the horrors of war without dipping his camera in blood.” In war-torn Vietnam he traveled to both the south and the north—one of few Western photographers to be allowed entry to the north. Riboud photographed haunting scenes of the destruction of the city of Huế, which he called “Vietnam’s Guernica”: during the grinding battle to capture the town from the North Vietnamese, US forces had bombed and destroyed 80 percent of the city. Absorbing the lessons of the post-World War II photography of his colleagues in Europe—Chim, Werner Bischof, and Ernst Haas—Riboud documented his characters against a theatrical background of ruins, contrasting scenes of everyday hope and survival, such as street vendors under their umbrellas and women leading animals to the market, with the eternal symbols of war—amputees, mountains of rubble, makeshift shelters amid utter destruction.

Advertisement

In 1957, when Riboud had first gone to China, the brief period of freedom of speech and artistic discovery known as the Hundred Flowers Campaign quickly changed to a more repressive phase with Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. Two portraits from the period stand out: the weary but graceful beauty of a Chinese peasant on a train, hugging her face between her intertwined arms; and a slim, severe old lady in a fur-collared cape, walking while holding an unlit cigarette—everything in the image tilts, except the thin white shape of the cigarette, a firm vertical.

Riboud formed a deep connection with China, where he would return twenty-two times until his final visit in 2010, not only taking photographs himself, but also meeting and encouraging a number of Chinese photographers, with whom he formed lasting bonds, and helping to found the first Chinese photo festival in Pingyao. He tracked the country’s gradual transition, after Mao’s death, to a consumerist society, with Shanghai supermarkets and an image of a man in rags in front of advertising posters filled with smiling faces. “In China, yesterday, today, and tomorrow are mixed up and superimposed at every street corner,” Riboud once told me. His vision of the country was instinctual, kaleidoscopic, and often playful.

Near the end of his life (he died in 2016, aged ninety-three), Riboud’s photographs became more abstract and meditative. The exhibition’s final section is dedicated to his Chinese landscapes. Encouraged by the painter Zao Wou-Ki, Riboud photographed the jagged Huangshan mountains, their slopes lined with spiky pine trees; the peaks look as if they’ve exhaled the white mist that floats around their summits. The colors are subtly suggested, barely departing from monochrome, and evoke Sumi-e ink paintings. Perhaps, after years of wandering, the man who was once too shy to speak had found, in this majestic landscape, a silence mirroring his own—a sort of home.