This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

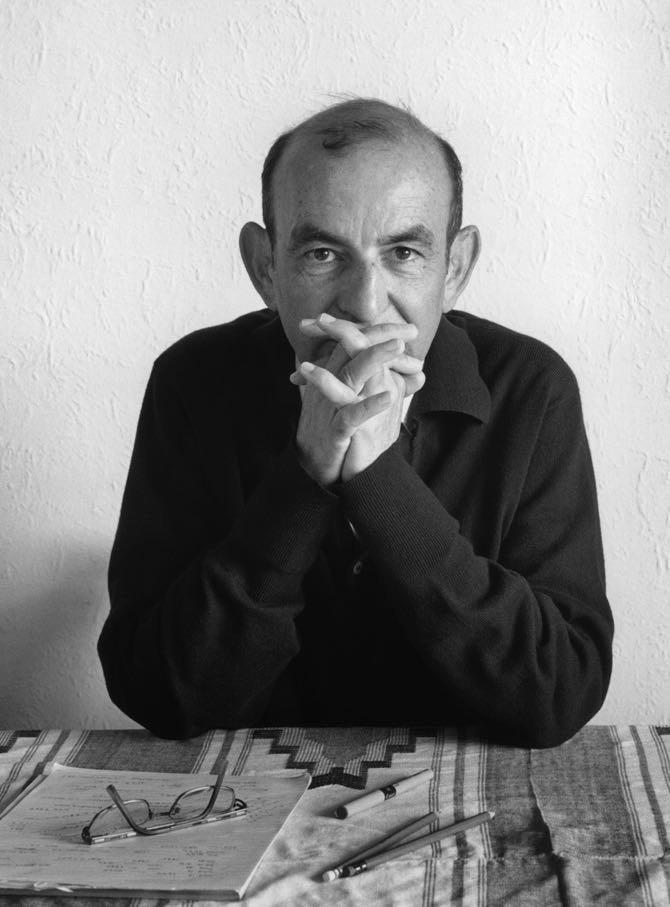

On October 1, 2021, we published Raja Shehadeh’s essay “The Nakba, Father’s Papers, and Jaffa Revisited.” Expanded from an address the Palestinian lawyer and writer recently gave at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, it touched on many of the themes and preoccupations that have animated Shehadeh’s books—among them, Strangers in the House (2001), Palestinian Walks (2007), and the upcoming We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I (2022).

As he relates in the essay, Shehadeh grew up hearing tales of his family’s life before 1948 and the war that led to Israel’s founding. The coastal city of Jaffa, their home, still has Palestinian inhabitants, but many—like his parents—fled the fighting or were forcibly evicted from their homes and became refugees. Shehadeh’s family resettled in Ramallah, in the West Bank, which was at that time under Jordanian rule but has been under Israeli occupation since the Six-Day War in 1967.

Shehadeh’s father, Aziz, though remote to young Raja, was an eminent Palestinian lawyer—a professional vocation he bequeathed to his son. Aziz acted as a legal and political adviser to the Palestinian leadership and, soon after the 1967 war, became one of the first advocates of a Palestinian state in the Occupied Territories. For the nascent PLO, then more enamored with “the gun” (armed resistance and guerrilla warfare) than the “olive branch” of a negotiated peace, Shehadeh’s outline of what would come to be called the two-state solution was unwelcome, its realism premature.

Even in this, Raja Shehadeh’s own legal career has shadowed his father’s experience. Now seventy, Raja spent his early working decades fighting over land claims in the military courts of Israel’s occupying administration. “My Ramallah world, with its proximity to the hills, was being transformed inexorably in a manner that mystified and frightened me,” he told me via e-mail earlier this month. “The changes taking place through the Israeli army’s takeover of the land using various spurious legal ploys and replacing the names of the various land features, towns, and villages with Hebrew names, as well as the changes in the narrative that accompanied the process, were all preceded by the alterations that were taking place in the local laws. These I was diligently following.”

The device of voiding Palestinian ownership claims and declaring property “state land” was part of a system that gradually enabled more and more of the occupied West Bank to be turned over to Israeli settlements. As early as the 1970s, this policy was described as “creating facts on the ground”—infrastructure and population centers that would become either bargaining chips in a peace deal or Zionist-annexed territory, de facto parts of Israel.

“He [Aziz] had a strong premonition that, in time, the religious right wing in Israel would gain power; and then the lobby for holding onto the whole of the Occupied Territories would strengthen and make the division of the land politically more difficult,” Shehadeh explained. And so it proved. “My legal project was to chronicle these changes and warn against their consequences,” he said.

This I pursued with the hope of raising awareness in order to exert pressure to halt Israel’s colonization of our land. But to no avail. It was when I realized the futility of that pursuit that my literary project began to take precedence. There, I tried to describe the exquisite beauty of the landscape that was under threat, in order both to preserve it in words and possibly give rise to a more effective lobby against these changes that the legal writing had not prevented. In this way, the two projects, the literary and the legal, intersected.

This sense of failure in his legal project, which echoed his father’s political defeat, is something that Shehadeh addressed in a review of David Shulman’s evocatively titled Freedom and Despair. Shehadeh writes feelingly about Shulman’s activist efforts to prevent settlers and the Israeli military from evicting Palestinians from their communities in the South Hebron hills as “a futile struggle.” It was a word he also used in our exchange:

The strongest sense of the futility of my legal project I experienced after I read the Oslo Accords in 1993 and saw that the Palestinian leadership had not taken into account any of my legal work or that of Al-Haq [the human rights group he founded in 1979]. The PLO ended up falling prey to the predictable Israeli traps by consolidating, through the terms of the accords, the unilateral changes in the law Israel had been introducing a decade and a half earlier. This greatly depressed me. I felt that I had wasted many years in a futile endeavor.

Then I remembered something I had read in the Bhagavad Gita:

You have a right to your actions,

But never to your actions’ fruits.

Act for the action’s sake.

I recalled that, despite the dismal outcome, those earlier years of activism when hope was still alive were, in fact, the best years of my life. So I concentrated on that and moved ahead by putting more energy and time into my literary project. My best books were written after the Oslo Accords were signed. From then on, I was carrying out an activity that no one could betray.

The action or activity that Shehadeh arrived at, which became the most telling device of his literary project, has been simply to walk, and then to narrate his walks. “When I started walking in the hills around Ramallah, Dolev was the only, rather peaceful Jewish settlement nearby,” he said. “The destruction of the landscape that was to occur later had not yet taken place. The peaceful hills still had great appeal to me. The slow vanishing of their pristine beauty as roads were constructed through them and more settlements were built became the subject of my writing: how that transformation was affecting me psychologically, engendering fear that the hills will never be the same.”

Advertisement

Walking became for Shehadeh a way not just of enjoying the physical landscape but also of asserting Palestinians’ enduring presence in the land—and, more figuratively, of giving the lie to the old Zionist canard about settling “a land without a people” by repopulating it with the history and memories of those who had lived there. Hence his constant revisiting of Jaffa, his ancestral home. Even if Palestinians, unlike Israelis, are denied the refugee’s “right of return” in practice, Shehadeh still exercises it imaginatively, with his walks through the city once known as “the bride of the sea”:

I thought that even if I spent a single night there in Jaffa, I could get some sense of the place and the atmosphere of life in that coastal city of my imaginings. And so, I continued to visit, but found that I had to rely more on my imagination because the reality was of an entirely different place from what my father had described…. I remembered my mother telling me that, just before they left, she could hear the echo of her footsteps on the empty sidewalks.