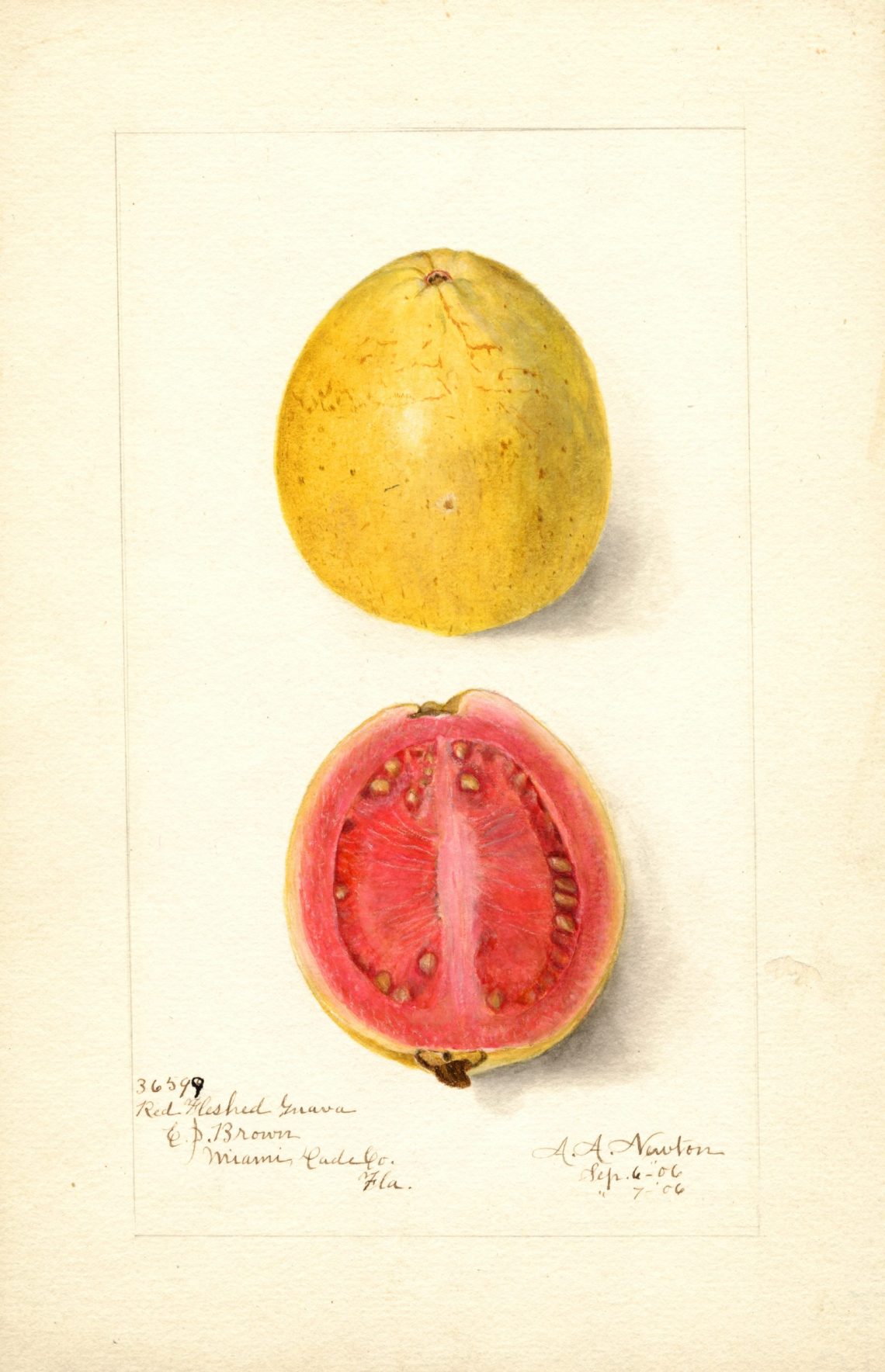

In a busy market in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka, the botanist David Fairchild, sporting a pith helmet, white suit, and large white mustache, ate a halved bael fruit with a tiny spoon. He examined betel nuts and grabbed the arm of a passing vendor to inspect the large bunch of coconuts balanced on his head. It was 1925, and Fairchild was leading an expedition to Ceylon, Sumatra, and Java on behalf of the United States Department of Agriculture in search of foreign plants to introduce to American growers, a trip documented in a silent film. After the market, the plant explorers visited a village where locals demonstrated various uses of the Palmyra palm, “a handsome and extremely valuable plant,” and carved open gigantic jackfruits.

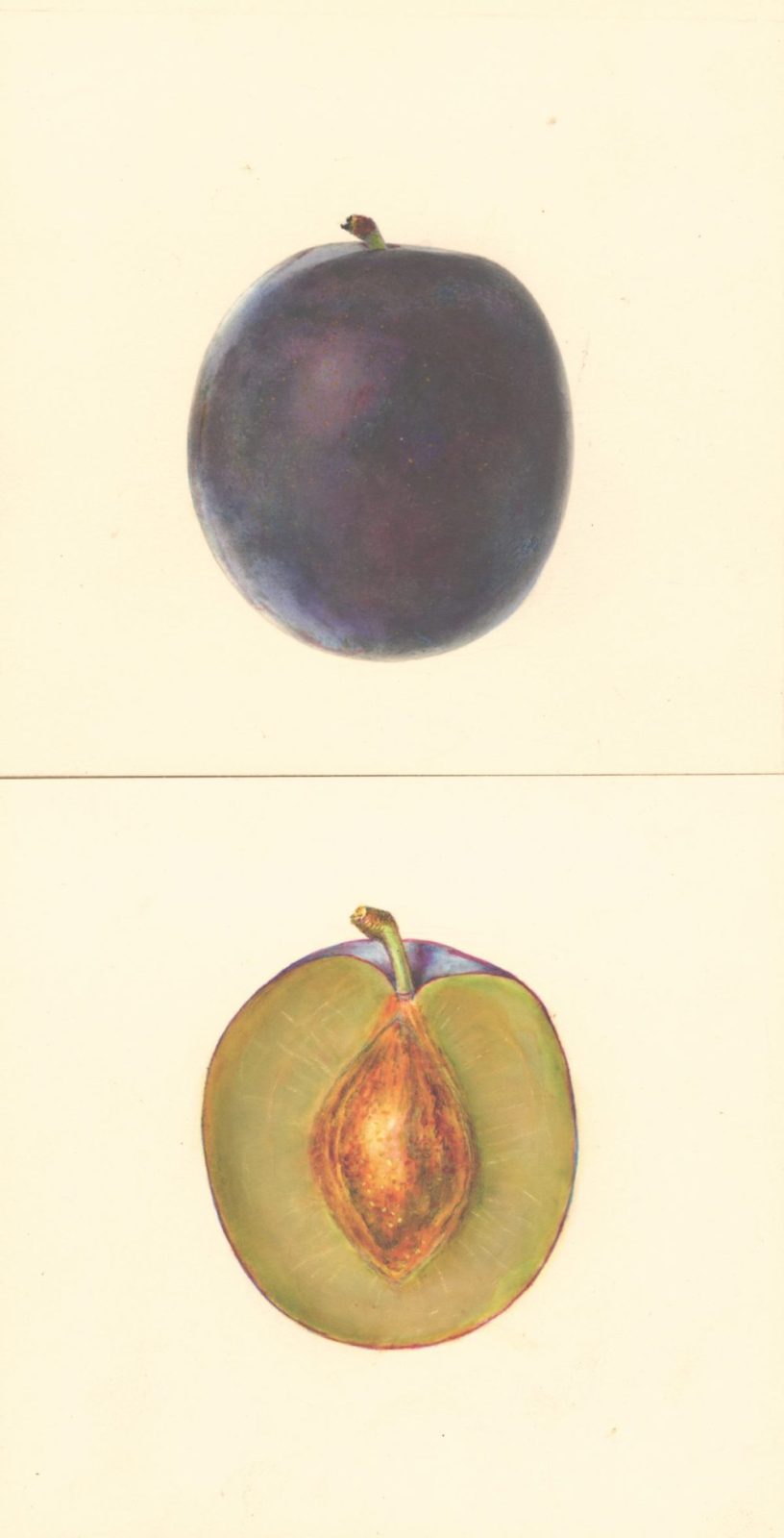

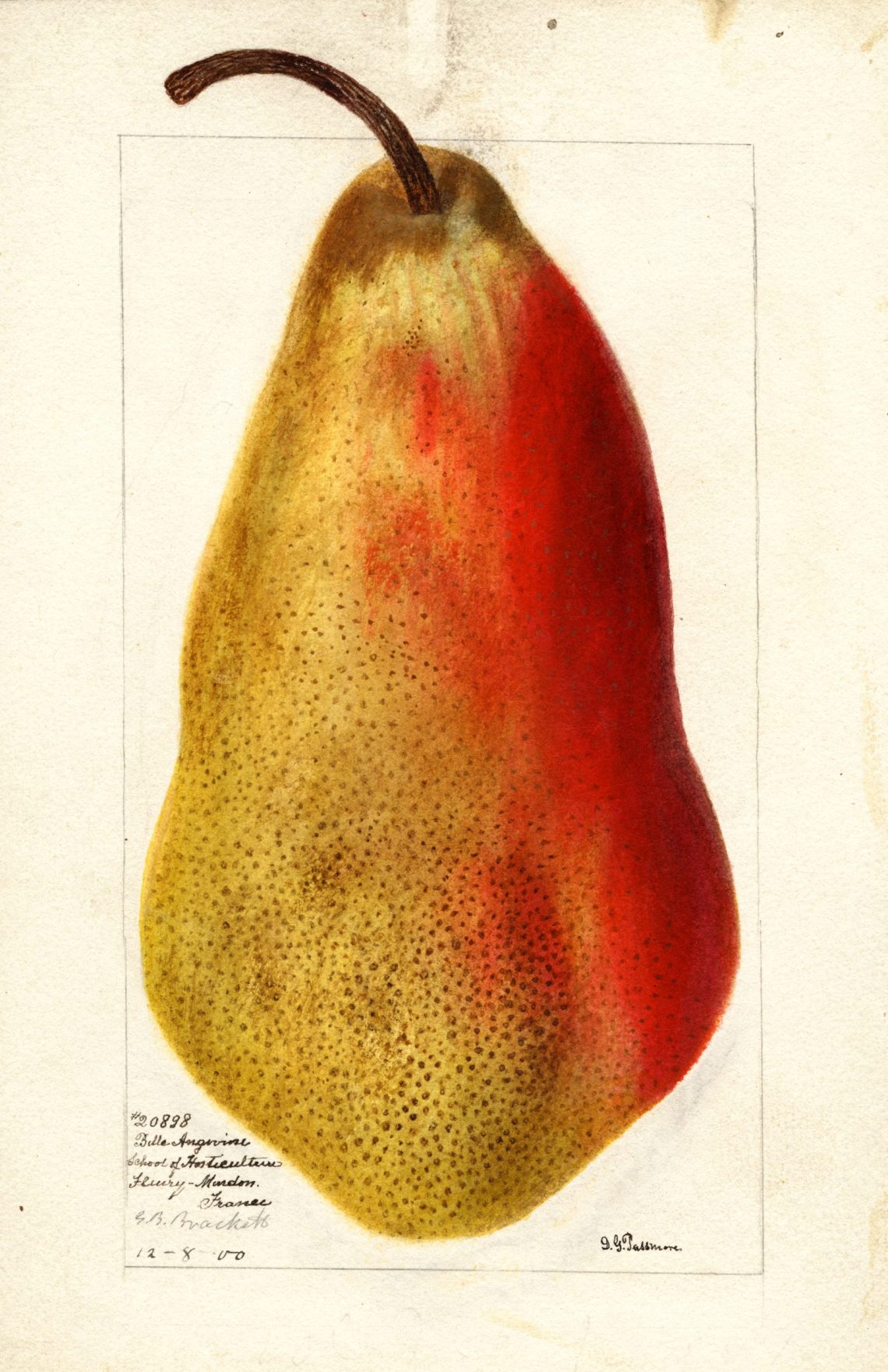

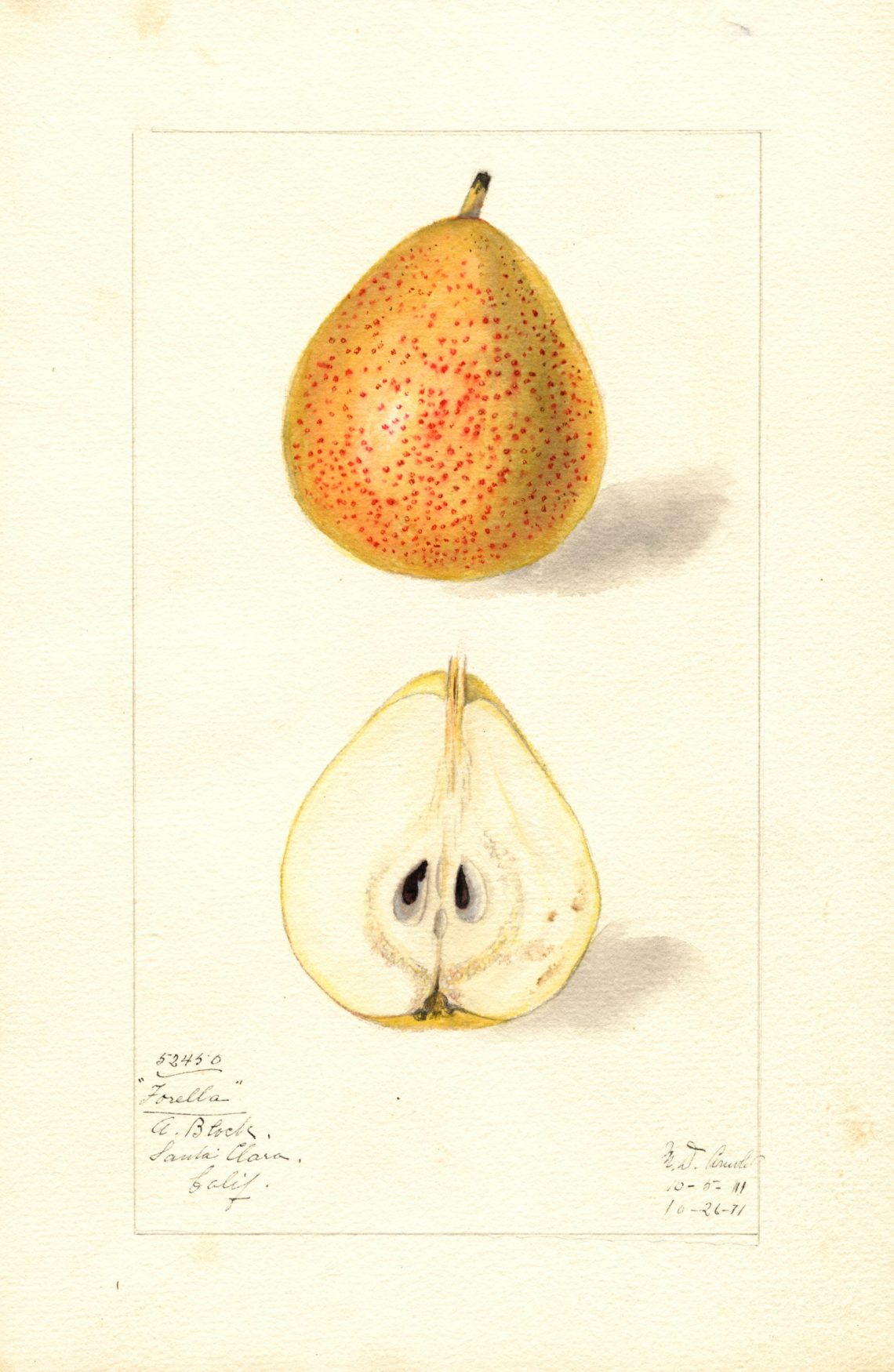

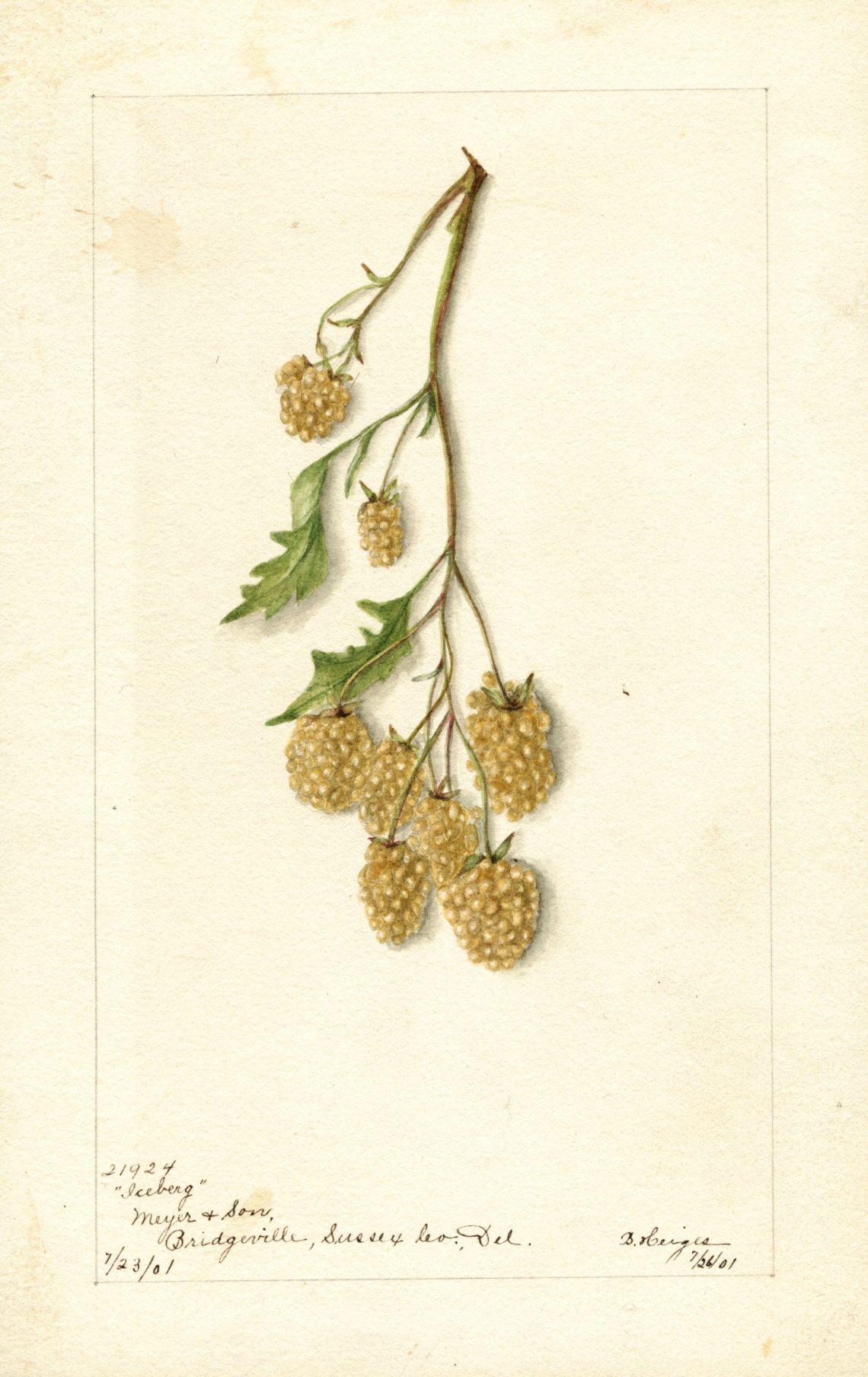

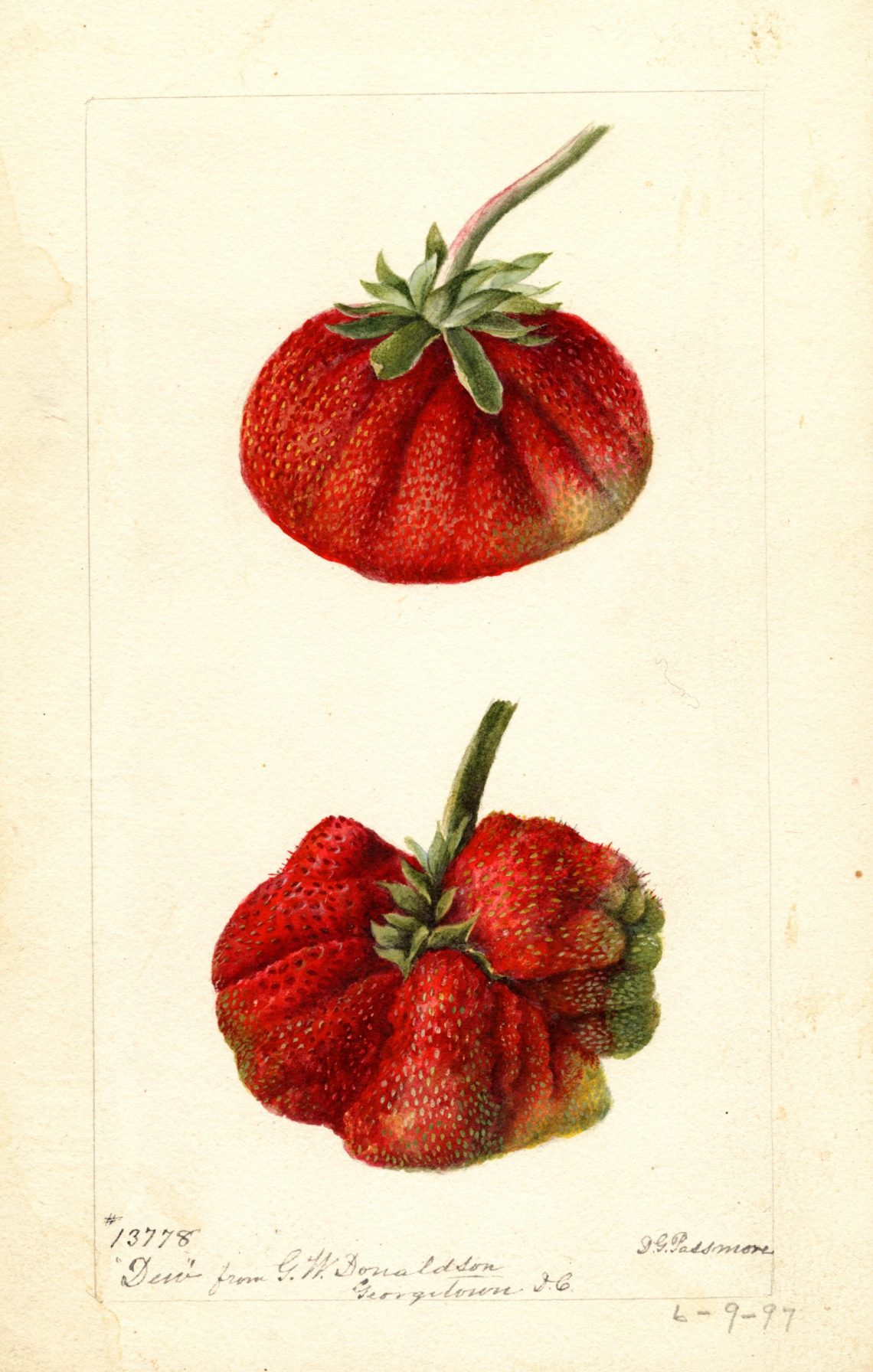

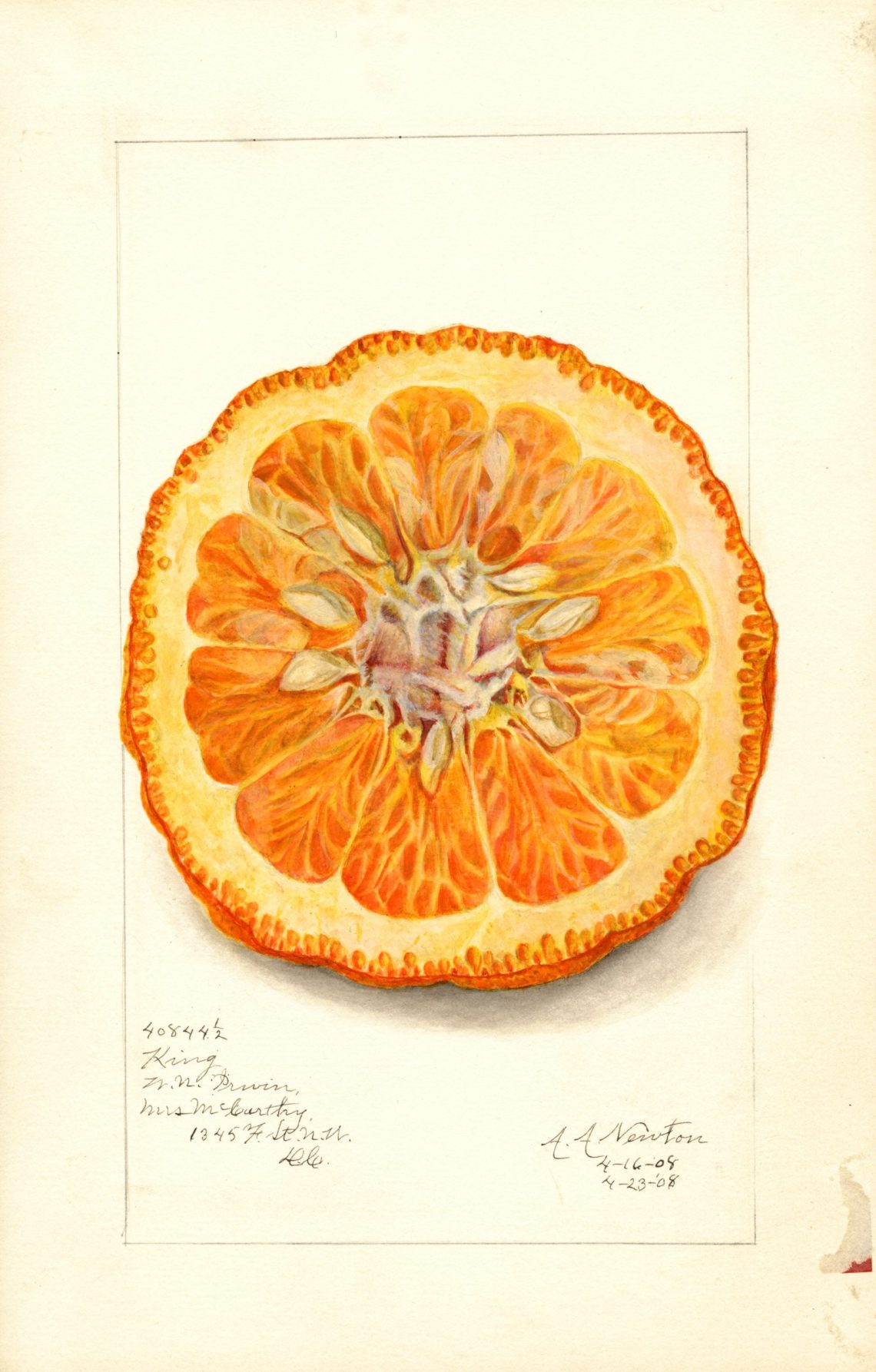

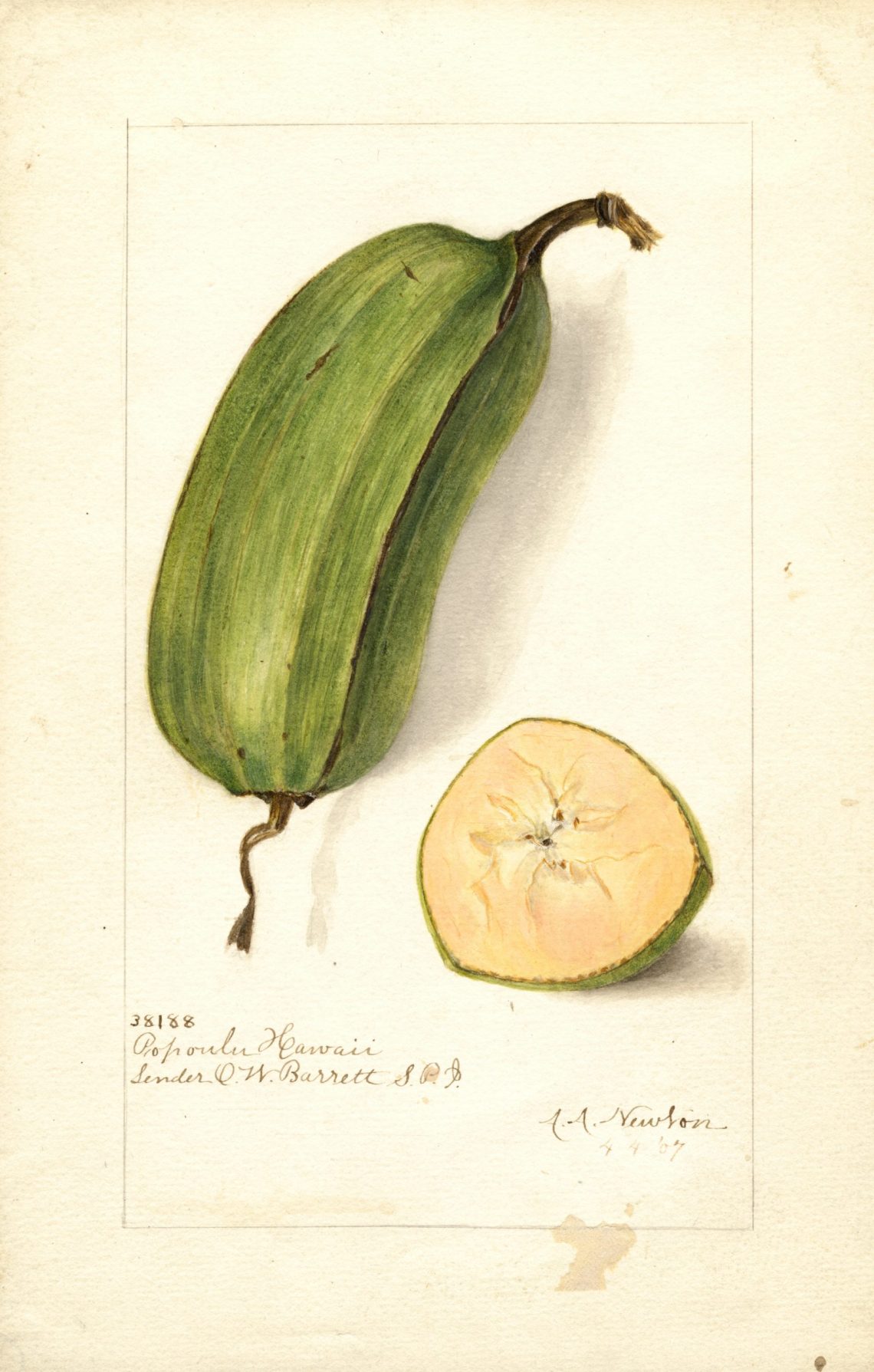

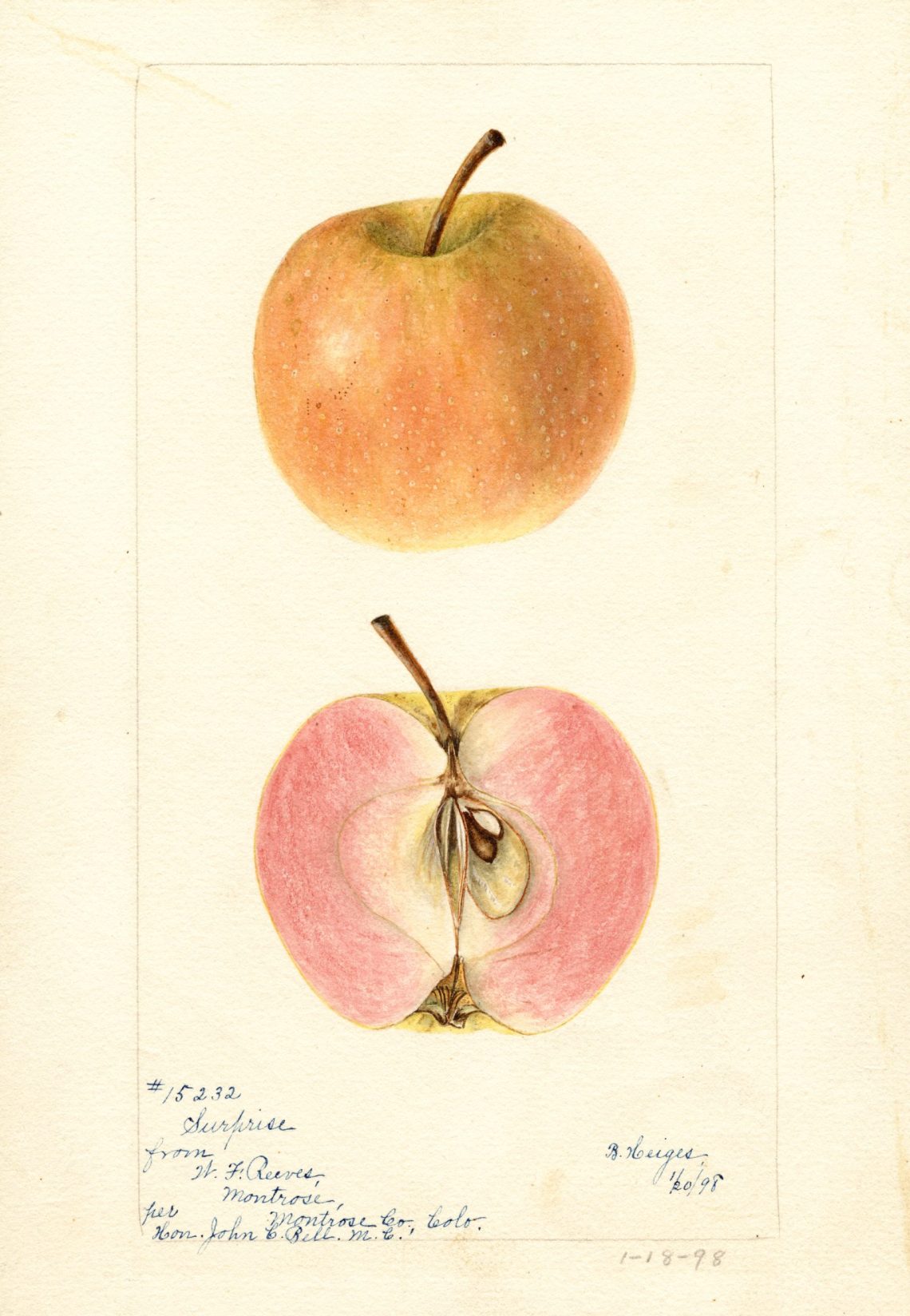

Fairchild was the head of the Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, a section of the USDA founded in 1898 to search the world for plants that could boost commercial agriculture at home and reduce economic reliance on imports. Atelier Éditions recently published a book documenting this project to expand the American palate: An Illustrated Catalog of American Fruits & Nuts, a sampling of watercolors from the department’s pomological collection. In a time before color photography was widespread, USDA artists, many with decades-long careers at the agency, created 7,584 technically accurate illustrations to record this cornucopia of the new. Along with short essays, including excerpted musings on fruit from Michael Pollan and John McPhee, the catalog contains the most visually striking of these images, from the incandescent King tangor to the dusky, green-fleshed Tragedy plum.

While fruits have never contributed as much to the economy as staples like soybeans, which last year brought $25.7 billion in exports as a result of varieties found by USDA explorers, they evoke more passionate cravings. Pineapples, native to South America and costly to grow in hothouses in northern climates, became a status symbol in Europe and colonial America; it was possible for middle-class households to rent individual fruits to show off as centerpieces at dinner parties, even if they could not afford to eat them. Until recent methods of refrigeration and transportation, fruit cultivation could defy even royal command: Queen Victoria was fixated on tasting a mango, but the fruit could not survive the six-week sea voyage from India.

Though we now eat fruits from every part of the globe in every season, the selection we enjoy is far more limited than the one promised by the USDA’s mouthwatering collection. The concerted efforts of plant explorers, researchers, breeders, marketers, government officials, entrepreneurs, and giant corporations enabled fruit to flow around the globe—but at a human, ecological, and ultimately gustatory cost.

*

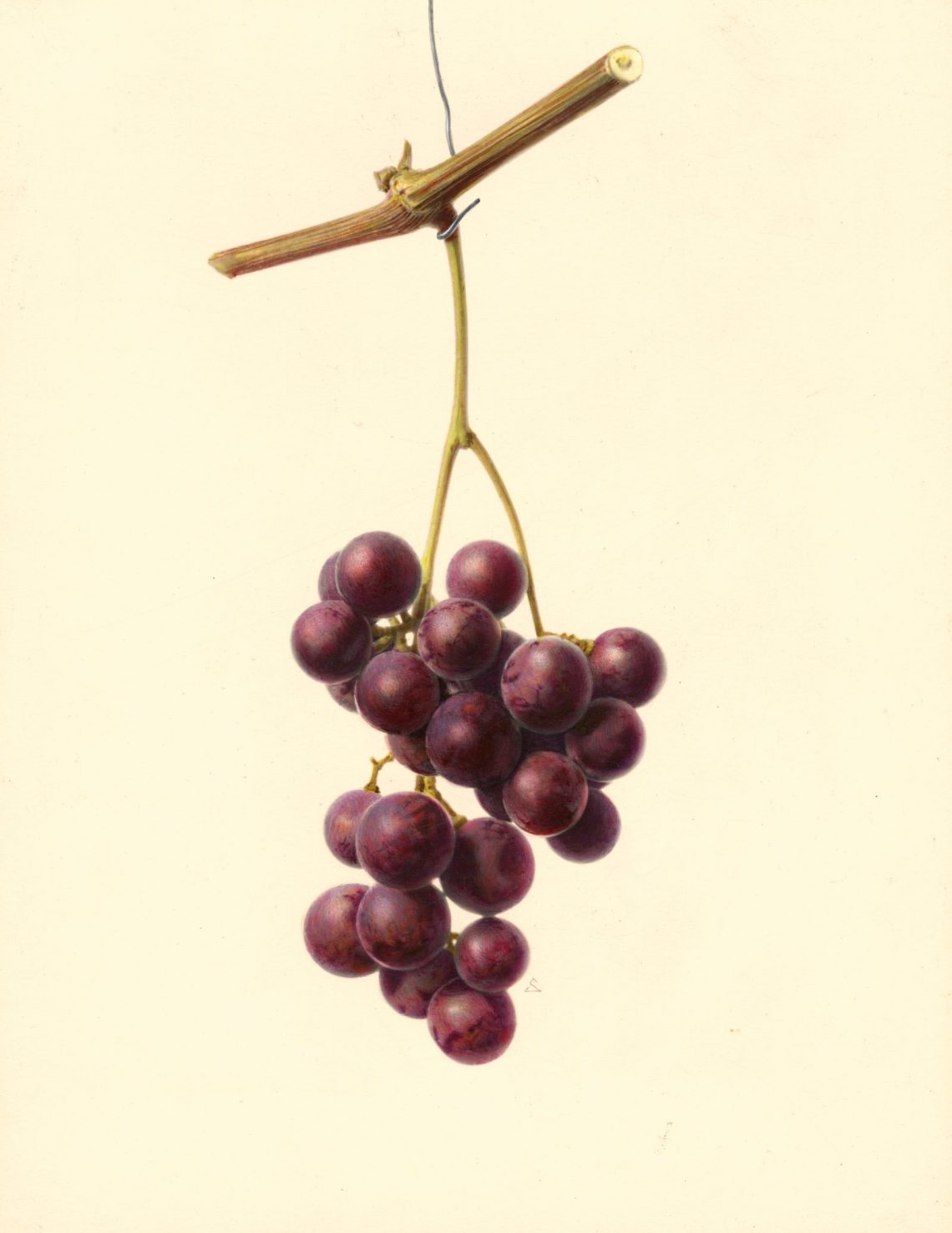

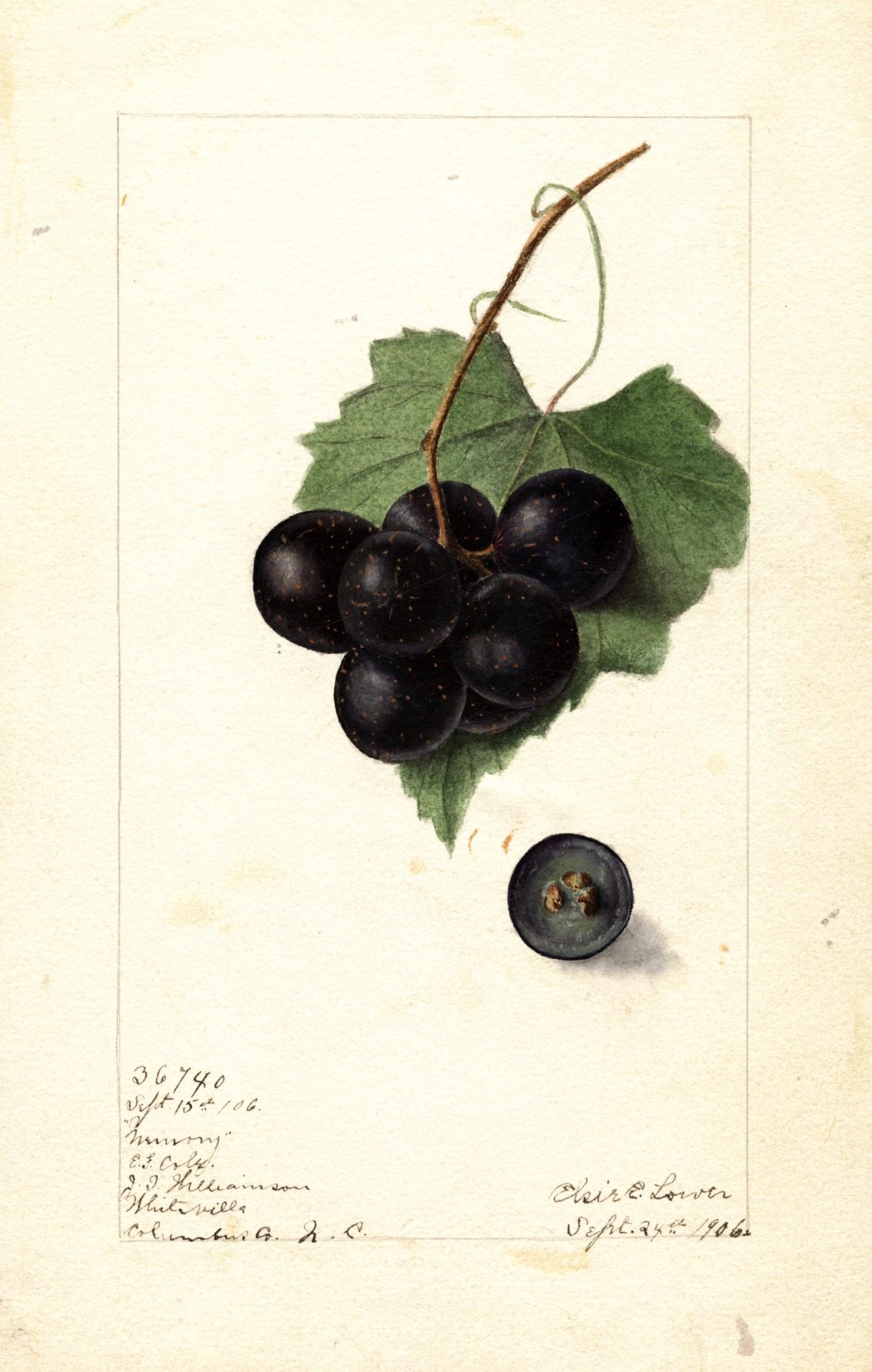

North America is the original home of cranberries, salmonberries, huckleberries, chokeberries, elderberries, serviceberries, thimbleberries, and buffaloberries. The largest native fruit is the pawpaw, whose custardy flesh has a tropical flavor incongruous with its ability to survive harsh midwestern winters. Pecans received their name from the Algonquin word “pecane,” which referred to any nut too hard to crack without a stone. The American persimmon is smaller and spicier than its Asian cousins; our grapes include the large, musky, thick-skinned Scuppernong, Muscadine, and Fox (the latter an ancestor of Concord grapes). Other domestic gems include black cherries, crabapples, and as many as thirteen plums. Around the time that fruit explorers went abroad, the USDA also pushed for the cultivation and distribution of some of this native bounty: in 1910, the agency published a bulletin calling growers’ attention to a “strangely overlooked” perennial, the blueberry.

Nearly all the other fruits grown in the US today are transplants. Citrus, originally from Southeast Asia, was established in the Mediterranean by around the second century BCE and brought to Florida and California by the Spanish. Cultivated apples, “American as pie,” are from the mountains of Kazakhstan. Peaches are from China, and watermelons from Northeastern Africa. From the nation’s earliest days, long before Fairchild’s Division of Pomology, gaining mastery over valuable plants was considered important to state-building. While in Europe, Benjamin Franklin would frequently exchange seeds through the mail with agriculturally-minded friends back home—in one letter from London he described sending rhubarb seeds, a variety of pea “highly esteemed here as the best for making pease soup,” and soybeans, which he called “Chinese garavances,” mistaking them for a variety of garbanzo bean. Thomas Jefferson experimented in his garden at Monticello with methods to grow crops from northern and southern Europe alongside African plants brought over by enslaved people, and asserted in 1790 that “the greatest service that can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

Advertisement

Through the nineteenth century, the diets of American settlers were heavy with meat, carbohydrates, and dairy, which could be produced and stored more reliably than fruits and vegetables. But this began to change with the spread of the steamship and railroad in the 1870s, as Daniel Stone describes in his 2018 book on David Fairchild, The Food Explorer. The banana, native to Southeast Asia and unknown to most Americans, debuted at the 1876 Philadelphia’s World Fair wrapped in foil and served with a knife and fork. New rail lines linking Florida to northern markets brought “orange fever,” as people flocked to the state hoping to cash in on the citrus gold rush. In 1917, Fairchild wrote that “The whole trend of the world is toward greater intercourse, more frequent exchange of commodities, less isolation, and a greater mixture of the plants and plant products over the face of the globe.”

In this time, USDA plant explorers had tremendous success in bringing new fruits within reach. Fairchild himself was responsible for introducing over 200,000 varieties of plants to the United States, including the flowering cherry trees that grow on the National Mall, marketable mangoes, and navel oranges. On a trip to Chile, he sent a shipment of nearly a thousand avocados to Washington, D.C.; from the few that survived the journey, the California avocado industry took root. Dates and nectarines he found in Baghdad were similarly profitable.

This collecting project was, at best, of no benefit to the countries being explored, as the food writer and historian Adam Leith Gollner notes in the introduction to the Illustrated Catalog: “The USDA’s undertaking, in terms of plant introduction, was itself an actor in the complex legacy of colonialism—one in which countries from the global North and West have extracted materials of value from the South and East in an exploitative, non-compensatory manner.” At worst, it was part and parcel of US imperial expansion taking place around the turn of the century. President William McKinley, asking Fairchild to carry out a survey of the agricultural potential of the Philippines in 1900 in the midst of the brutal Philippine–American War, wrote that “an American military presence might work in your favor.” Though Filipinos’ guerrilla tactics made a comprehensive assessment impossible—“they are not yet sufficiently pacified,” Fairchild complained—he still managed to snag a Carabao mango, which was critical to the US mango industry for the next century. After the US decisively gained control over the country in 1913, having committed numerous military atrocities there, the new colonial government invested heavily in agricultural production. Land devoted to coconuts expanded from one thousand acres to 1.4 million by 1934, making the Philippines the world’s largest exporter of coconut oil, much of it going to US markets.

Most tropical fruits cannot adapt to colder or drier climates and must be imported. This basic horticultural fact underlies a brutal history of American extraction, as companies established industrial-scale plantations in Latin America and the Caribbean. Plantation labor was surveilled and violently policed; workers lived in company dwellings and were paid in scrip, creating an essential continuity with earlier slave production of commodities like sugar. In Honduras the United Fruit Company took enormous land subsidies from the Honduran government in exchange for the construction and operation of a railroad that provided ample transport between agricultural regions and ports but did not connect to the capital city. The company was complicit in the Colombian military’s massacre of hundreds of striking plantation workers in 1928, and successfully lobbied US officials to overthrow the president of Guatemala in 1954 after he instituted land reforms. All for the ubiquity of the banana, which was aggressively marketed to Americans in the 1940s—the Chiquita jingle, instructing consumers how to eat and store bananas, was played on the radio as many as 376 times a day.

The Kingdom of Hawaii, led by Queen Liliʻuokalani, was overthrown in 1893 by a group of businessmen and sugar planters who felt that it would be beneficial to be annexed by the country that imported the bulk of their agricultural products. The leader of this coup and first governor of the new territory, Sanford Dole, was the cousin of James Dole, who would soon establish the world’s largest pineapple company on the islands. A list of the places to which David Fairchild’s seeds were sent to be cultivated—Cuba, Honduras, the Panama Canal Zone—provides a revealing map of US influence and control around the world at the turn of the century, a time when the US was using dubious legal devices to create de facto colonies while maintaining plausible deniability about its status as an imperialist power. The USDA opened experimental stations in Hawaii and Puerto Rico to receive shipments of tropical plants that wouldn’t survive at headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Advertisement

By the dawn of World War I, public enthusiasm for colonial administration was waning, and backlash to an era of rapid globalization stoked nativist fears about foreign contamination. The entomologist Charles Marlatt frequently clashed publicly with Fairchild—the men had been childhood friends before their feud—as he argued that the import of so many exotic plants was causing America to become overrun with disease and “foreign insect enemies.” Invasive pests were indeed a problem: Marlatt had seen the San Jose scale, an insect, decimate fruit trees in California in the 1880s after it was accidentally introduced on Chinese peach trees (he later traveled to China to find the scale’s natural predator—and returned with the ladybug). The US was one of the last wealthy nations without any restrictions on importing live plants, until Marlatt’s efforts paid off and the Plant Quarantine Act passed in 1912. Though the law was relaxed somewhat after World War II, when the global mood again swung towards internationalism and trade liberalization, it effectively put an end to the unregulated heyday of the plant explorers.

*

Fairchild’s dream of bringing the boundless variety of the world’s fruits to Americans went unrealized in other ways. An unforeseen consequence of his work was the rise of industrial monoculture to grow the most profitable varieties in the cheapest locales, at the expense of native and heirloom varieties. In the 1860s, New England was in the grip of a “pear mania,” an enthusiasm for amateur horticulture which irked Henry David Thoreau, who felt pears were a finicky and “aristocratic” fruit compared to the apples he loved. “The hired man gathers the apples and barrels them. The proprietor plucks the pears at odd hours for a pastime, and his daughter wraps them each in its paper,” he wrote. “Judges & ex-judges & honorables are connoisseurs of pears & discourse of them at length between sessions.” He might have been less judgmental had he known that Bartlett pears would soon become available by train from California, where trees could bear heavier crops than in the East. Of the 2,683 pear varieties recorded in use between 1803 and 1903, 88 percent were extinct by 1982. Indeed, the US grows far fewer commercial varieties of most fruits than it did one hundred years ago. It is dismaying to flip through the Illustrated Catalog’s abundance of grapes—including the inky Memory, oblong Rose d’Italie, and maroon Requa—and think of the two options available in the supermarket: “red” and “green.”

Fairchild was eager to see his favorite fruit, the “indescribably delicious” mangosteen, available in the US, but in addition to requiring the moist, humid growing conditions of Southeast Asia, it bruises easily and won’t ripen after being picked. The pawpaw is also considered too fragile to make the bumpy truck journey to stores. While it is now possible to ship intensely flavorful mangoes from India, as Victoria once dreamed, it’s too expensive to be worthwhile at anything larger than a boutique scale. Instead, we are stuck with the insipid red and green Tommy Atkins, which was rejected numerous times by the Florida Mango Forum Variety Committee when it was first discovered, in the 1950s, for being bland and fibrous—“not a connoisseur’s mango.” But the fruit was disease resistant, difficult to damage, and visually appealing: a trifecta that, in the global market, nearly always trumps taste.

The greatest success of fruit mass production, and perhaps its greatest cautionary tale, is the banana. There are more than a thousand varieties of banana, but 99 percent of those exported to the US and Europe are the hardy Cavendish, and all Cavendish bananas are clones, propagated from cuttings that can all be traced back to one original plant (as are Granny Smith apples, navel oranges, and many other commercial fruits). Unfortunately, being genetically homogenous and grown in the tropics makes the Cavendish highly susceptible to disease. In the 1950s, a fungus known as Panama disease rapidly spread through United Fruit’s empire and virtually obliterated the Gros Michel banana, once as widespread as the Cavendish (and said to be more flavorful). United Fruit researchers’ efforts to find a fungicide that could control Panama disease, though unsuccessful, ushered in a new era of rampant pesticide use. The application of the pesticide DBCP between the 1960s and 1980s caused the sterilization of plantation workers in five countries, and other chemicals continue to cause high rates of cancer and respiratory disease among banana workers.

Agrobiodiversity is in stark decline worldwide. To hedge against an increasingly precarious food supply, the USDA now conserves many wild or discontinued varieties in seed banks and germplasm repositories, including one of the world’s largest collection of apples in Geneva, New York. The Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, founded in 1936 and home to many plants Fairchild personally collected, has changed its mission from the introduction of new plants to the preservation of endangered Floridian species, and protects the genetic diversity of a large tropical fruit collection. Many of Fairchild’s samples are no longer grown anywhere else, having been crossbred out of existence. After decades of hybridization in pursuit of new cultivars, there is now some dawning recognition of what has been lost in the shuffle.

Seed banks alone, of course, can’t restore local foodways: in the US, that work is being done by groups like I-Collective, a coalition of Indigenous chefs, herbalists, seed-keepers and others working on projects related to food sovereignty. There are also organizations like the Neighborhood Planting Project, a group in Bloomington, Indiana, that goes door to door offering to plant native fruit-bearing shrubs and trees like pawpaws, crabapples, hazelnuts, and persimmons in front yards at no cost. (So far, they have given away over seven thousand plants.) Next year the artist Sam Van Aken will plant an orchard on Governor’s Island in New York, each tree with a number of native or lost heirloom species grafted onto their branches. The fruits will be shared with the public, “giving everyone a chance to see and taste fruits that, in some cases, haven’t been available for centuries.”

Decades of Red Delicious dominance in the produce aisle have left customers looking for better. On the one hand, this has led to a movement of local agriculture; on the other, to ever more rigorous breeding and genetic engineering programs to create produce better suited for the industrial food system, like apples that won’t brown when exposed to air and can be sold presliced in plastic bags. It’s possible such new technologies will find ways to avoid the trade-off between taste and the unlimited accessibility we have been promised, but markets tend to cater to our simplest desires, for the shiny, the seedless, and the sweet (two of the most successful recent designer fruits have been Honeycrisp apples and Cotton Candy grapes). It is easy to forget that fruit is not a commodity first, but part of a living organism that, when bound to a place and season, can both surprise and satisfy.

In his 1862 essay “Wild Apples,” Thoreau describes an apple-picking walk through the Massachusetts countryside in November as a full sensory experience, in which the fruit can only be appreciated as part of the environment that produced it—as a way to taste late autumn. “These apples have hung in the wind and frost and rain till they have absorbed the qualities of the weather or season, and thus are highly seasoned, and they pierce and sting and permeate us with their spirit. They must be eaten in season, accordingly,—that is, out-of-doors.” Wild apples, randomly cross-pollinated by bees, have a wide range of flavors, sometimes even when grown from the same tree, and a love for them requires a palate that can tolerate the occasionally sour, gnarled, irregular, intense. This is a kind of novelty that has been eradicated in our quest for endless choice. Thoreau himself predicted that “The era of the Wild Apple will soon be past…I fear that he who walks over these fields a century hence will not know the pleasure of knocking off wild apples. Ah, poor man, there are many pleasures which he will not know!”