David Park (1911–1960) is one of those artists who isn’t widely known but whose work inspires a special loyalty and warmth of feeling among his admirers. The partisan flavor his very name can arouse is partly dependent, of course, on his not being a household name to begin with. But Park, who was based in Berkeley, California, and was, along with Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff, one of the leading lights of what has been called “Bay Area” painting in the 1950s, makes some of us always eager to see more of his work and learn more about him because his best pictures have a particular tenderness and sense of gravity—a note that sets him apart from near-contemporaries of his such as Alice Neel, Fairfield Porter, or Alex Katz.

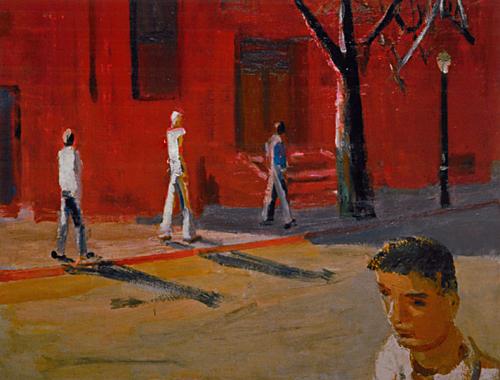

Not that there is anything sentimental or literary—or modest in scope—about Park’s painting. In his pictures of, say, people at a dining-room table, young men walking, musicians at work, or in his portraits, he doesn’t spell out specific expressions. Most of his energy has gone into his feeling for the shifts in the inner space of an image and for the creation of light, which he can make sizzlingly bright or glowingly soft. A person’s eyes, in a Park, might be no more than dots. Yet the magic of his brushy and muscular paintings, often marked by hot reds, yellows, and oranges, is that the people in them have psychologically full presences, and we are pulled into the reflective spirit of the images.

It is not surprising that Park has long been written about with fervor and affection. Also unsurprising is that most of the commentary is to be found in gallery catalogs which, like that for the Whitney Museum’s 1988 Park retrospective, are out of print. There has never been a full-fledged biography or conventional big picture book. Helen Park Bigelow’s David Park, Painter: Nothing Held Back is thus long overdue. This account by the artist’s younger daughter provides the first intimate look we have had of him, and the volume itself, while not especially extravagant, can be called the first coffee-table book on David Park.

Given that there probably won’t be any publications like it any time soon, however, it is unfortunate that Bigelow includes so many of Park’s early, somewhat styleless pictures, done when he was finding his themes, and also so many of his paintings from 1958 and 1959 of vaguely everymanish heads and nude figures. They can be wooden and portentous. And this selection sorely needs more of what, I believe, makes Park most distinctive: his pictures of people, anchored in specific, everyday situations, done through the first two thirds of the 1950s.

In paintings such as the 1950 Kids on Bikes, for example, Park brought to American art a note of informality—a feeling for the relaxed clothes people actually wore and for fleeting unannounced moods and moments—that was in its way as new and as expansive in spirit as what Jackson Pollock was doing at the same time. (Works on this order that I miss in Bigelow’s volume include Bus Stop, Jazz Band, Kids on Bikes No. 2, Blue Lydia, Flower Market, Boy and Car, Tournament, and his portraits of children.)

Bigelow’s text has a drawback, too. It won’t satisfy readers looking to understand the ins and outs of Park’s career or where he stands in relation to American art in general, let alone world art. But her gentle and gracefully written portrait does feed our need to know more about the person her father was. A little like Musa Mayer in Night Studio, Mayer’s memoir of her father Philip Guston, Bigelow engagingly describes the experience of growing up with a parent who was a driven artist. Her best passages have something of the unaccountably emotional texture of her father’s art. In one of them, describing a moment in 1945 when she was twelve and her father’s two brothers were visiting, the family is playing charades, and she finds herself and her teammates, who turn out to be her father and his brothers, in a small closet, looking for props. At the moment, she is flooded with happiness in having this sudden, singular intimacy, a feeling that becomes only enhanced when she realizes that her father is smiling at her, and “I saw that he knew exactly how I felt.”

The David Park who emerges in his daughter’s book is much the same elusive, sweet-natured, and tense, or complex, man we might have expected. A high-school dropout from a Boston family whose father was a Yale-educated Unitarian minister (and whose grandfather and great-grandfather were ministers), Park had a continual need to face the world as a regular guy. He was always on guard against self-importance, in himself or anyone else; yet, as Bigelow makes clear in a telling anecdote, he was fiercely ambitious. His pictures, in turn, are unusual in the way they so often show people coming together, whether to play music or eat or walk through the woods or simply to stand by one another; yet few American artists have so powerfully captured the state of being isolated in one’s thoughts.

Advertisement

David Park, Painter: Nothing Held Back by Helen Park Bigelow. Hudson Hills Press, $60.00